How to cite this article: Joshua N. Tilton, David N. Bivin, and Lauren Asperschlager, “Man’s Contractured Arm,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2025) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/30940/].

Matt. 12:9-14; Mark 3:1-6; Luke 6:6-11[1]

וַיְהִי בַּשַּׁבָּת וַיִּכָּנֵס לְבֵית הַכְּנֶסֶת וְהִנֵּה אָדָם יְמִינוֹ יְבֵשָׁה וַיִּשְׁאָלוּהוּ לֵאמֹר הֲיֵשׁ בַּשַּׁבָּת לְרַפְּאוֹת וַיּאֹמֶר לָאָדָם קוּם וַעֲמֹד בַּתָּוֶךְ וַיָּקָם וַיַּעֲמֹד וַיּאֹמֶר לָהֶם אֲנִי שׁוֹאֵל אֶתְכֶם הֲיֵשׁ בַּשַּׁבָּת לְקַיֵּם נֶפֶשׁ אוֹ לְאַבְּדָהּ מִי בָּכֶם אָדָם שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ שֶׂה וְאִם יִפֹּל בַּשַּׁבָּת אֶל פַּחַת הֲלֹא יְקַיְּמֵהוּ עַל אַחַת כַּמָּה וְכַמָּה אָדָם שֶׁחָמוּר מִשֶּׂה וַיּאֹמֶר לָאָדָם שְׁלַח יָדְךָ וַיִּשְׁלַח יָדוֹ וְהִנֵּה שָׁבָה כִּבְשָׂרוֹ וַיְדַבֵּר אִישׁ אֶל רֵעֵהוּ לֵאמֹר מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה לְיֵשׁוּעַ

And it happened on the Sabbath that Yeshua entered a synagogue. A person was there whose right arm was contractured. They asked Yeshua, “Is there a duty on the Sabbath to heal?” But Yeshua said to the man, “Rise and stand in the center.” So he rose and stood. Then Yeshua said to them, “I will ask you a question. Is there a duty on the Sabbath to preserve life or to destroy it? Who among you has a sheep? If the sheep falls into a pit on the Sabbath, wouldn’t you preserve its life? Then how much more in the case of a human being!” To the man Yeshua said, “Stretch out your arm!” And he stretched it out. And behold! It returned from being contractured to being the way his flesh should be. And each discussed with his neighbor saying, “What can we do with Yeshua?”[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Man’s Contractured Arm click on the link below:

Story Placement

In all three of the Synoptic Gospels Man’s Contractured Arm occurs as the sequel to Lord of Shabbat.[3] However, the strength of the connection between these two episodes differs among the three Gospels.

The weakest connection between the two episodes is in Luke, which states that the events described in Man’s Contractured Arm took place ἐν ἑτέρῳ σαββάτῳ (en heterō sabbatō, “on another Sabbath”; Luke 6:6). Luke’s phrase allows for, but does not imply, chronological sequence. What took place in Man’s Contractured Arm happened on “another” Sabbath than the events described in Lord of Shabbat. Man’s Contractured Arm could just as easily be a flashback to an earlier point in the chronology as it could be a jump forward in time. The two episodes are collated because the subject matter (Sabbath observance) is the same, not because one event happened before or after the other.

In Mark’s Gospel the connection between the two episodes is stronger. The two events are not clearly distinguished as having taken place on different Sabbaths. Rather, Mark informs his readers that Jesus “again” entered the synagogue (Mark 3:1). Unlike Luke’s “on another Sabbath,” Mark’s “again” does imply chronological sequence:[4] Jesus first debated Sabbath observance with the Pharisees in Lord of Shabbat, and later, in Man’s Contractured Arm, Jesus debated with them “again.” Mark’s wording allows for the possibility that after the encounter with the Pharisees in the barley field described in Lord of Shabbat Jesus made his way to the synagogue.

That Mark’s narrative could be understood in this way is proven by Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm, in which Jesus, departing “from there” (i.e., the barley field), comes to the synagogue (Matt. 12:9). Matthew’s version leaves no doubt that the two events took place one after the other. This progressive strengthening of the ties between Lord of Shabbat and Man’s Contractured Arm is a literary phenomenon that is consistent with Lindsey’s hypothesis that the transmission of the synoptic tradition went from Luke to Mark to Matthew.

The weak connection between the two episodes in Luke’s Gospel is likely to be the most historically accurate. The differing casts of characters suggest that the two episodes took place at different stages of Jesus’ career. In Lord of Shabbat the cast of characters includes the disciples, who are not merely present but central to the plot. It is their conduct that certain of the Pharisees questioned. It is clear, therefore, that Lord of Shabbat took place well into Jesus’ public career. By contrast, in Man’s Contractured Arm the disciples are not among the cast of characters.[5] The disciples are not even mentioned as bystanders or witnesses to the event. Their absence from the story suggests the events described in Man’s Contractured Arm took place before Jesus acquired a following of disciples.[6] Thus, the possibility that Man’s Contractured Arm is a chronological “flashback” is likely confirmed. The placement of Man’s Contractured Arm next to Lord of Shabbat is thematic, not chronological, and these pericopae may owe their collocation to the Anthologizer, who, according to Lindsey, rearranged the stories of Jesus according to subject matter.

On account of the disciples’ absence from this pericope we have placed Man’s Contractured Arm in the section of Jesus’ biography labeled “Yeshua, the Galilean Miracle-Worker,” which takes place before Jesus began calling disciples.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

Most scholars assume that Mark’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm was the source for Luke’s[7] and Matthew’s.[8] However, we have already encountered some evidence—the tightening of the bonds between Lord of Shabbat and Man’s Contractured Arm that progresses from Luke to Mark to Matthew—that calls this assumption into question.

Further evidence for a Luke to Mark to Matthew sequence of transmission is found at the conclusion of the pericope. In Luke’s version the conclusion is low-key and credible. It accords well with other stories about charismatic wonder-workers in ancient Jewish sources, and it reverts well to Hebrew. In Luke’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm the baffled observers discuss “what they might do with Jesus” (Luke 6:11), since although they were uncomfortable with Jesus’ approach, Jesus had not actually done anything objectionable. Indeed, Jesus had not done anything at all—God had healed the man’s arm in apparent confirmation of Jesus’ opinion[9] —so there was nothing the spectators could do with Jesus except let him go on his way.

The situation is similar to a story in the Mishnah about the charismatic wonder-worker Ḥoni the Circle-Maker, who prayed for rain in an abrupt and forthright style.[10] Whereas the Pharisaic leader Shimon ben Shetaḥ personally objected to Ḥoni’s impetuous manner toward God, God’s answer to Ḥoni’s prayer demonstrated that “the butler is more regal than the king.” If God was willing to accept Ḥoni’s impetuous manner, then Shimon ben Shetaḥ would have to accept it too: צַרִיךְ אָתָּה לִנַדּוֹת אֲבַל מָה אֶעֱשֶׂה לָךְ (“You ought to be excommunicated, but what can I do with you?”; m. Taan. 3:8). Even the formulation of the Pharisees’ question resembles the discussion of the onlookers in Luke 6:11 concerning τί ἂν ποιήσαιεν τῷ Ἰησοῦ (“what they might do with Jesus”).

In Mark the response to the healing of the man’s arm is quite different. The Pharisees plot with the Herodians “how they might destroy” Jesus (Mark 3:6). Their reaction is wildly disproportionate to the situation, since Jesus did nothing in violation of the Sabbath. The conclusion in Matthew is substantially the same as Mark’s, except for a few stylistic improvements and the omission of the mysterious Herodians.

Some scholars have suggested that, for one reason or another,[11] the author of Luke toned down Mark’s conclusion to the story.[12] But secondary redaction in Greek does not result in a story that is more credible, more Jewish, and more Hebraic than the original. As Flusser observed, “Water does not flow uphill. It is simply impossible to believe that the Matthean-Markan account could be changed secondarily into the Lukan form.”[13]

Thus, Lindsey’s Luke-to-Mark-to-Matthew model finds powerful confirmation in Man’s Contractured Arm. This is not to say, however, that Luke’s version of the pericope has not undergone various stages of redaction. Indeed, there are several indications that for Man’s Contractured Arm the author of Luke relied not on the Anthology (Anth.), the translation-style Greek source he shared with Matthew, but on his more refined Greek source, the First Reconstruction (FR). Among these indicators are grammatical constructions (ἐγένετο + time marker + infinitive as main verb [L1-3]), vocabulary (σώζειν [L23]), and thematic motifs (scrutinizing Jesus [L8] with malicious intent [L12]; Jesus’ awareness of what others are thinking [L13]) typical of the First Reconstructor’s redactional style (see the Comment section below). Luke’s reliance on FR for Man’s Contractured Arm would also partially account for the relatively few Lukan-Matthean minor agreements against Mark in this pericope, since minor agreements in FR pericopae are only possible when the First Reconstructor transmitted Anth.’s wording to Luke at the same points where the author of Matthew preferred Anth.’s wording over Mark’s.[14]

The author of Mark based his version of Man’s Contractured Arm on Luke’s, but he pursued his usual method of paraphrasing and dramatizing. The most important change the author of Mark made to the pericope was to foreshadow, at such an early stage in his Gospel, the Passion narrative. This foreshadowing occurs in the rewritten conclusion of the story (Mark 3:6), in which the author of Mark describes the plot to destroy Jesus.

Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm stands out from the others in that it contains an analogy between healing on the Sabbath and assisting a sheep that has fallen into a pit on the Sabbath. Although this analogy is not present in the Lukan or Markan parallels to Man’s Contractured Arm, there are two parallels to this argument elsewhere in Luke. In Daughter of Avraham (Luke 13:10-17) the setting is similar: on a Sabbath Jesus encounters in the synagogue an infirm woman. Jesus argues that just as one may untie an ox or a donkey on the Sabbath to lead it to water, so the woman should be released from Satan’s power. Even more similar to Matthew’s analogy in Man’s Contractured Arm is the argument that Jesus makes in Man With Edema (Luke 14:1-6) that just as one would save his son or ox from drowning in a cistern on the Sabbath, so one should save the man with edema from succumbing to the excess fluids in his body, even on the Sabbath. On account of these similarities some scholars have supposed that the author of Matthew imported the analogy about the sheep in the pit from one of these stories into his version of Man’s Contractured Arm,[15] perhaps to compensate for his omission of Daughter of Avraham and Man With Edema.

Although positing a common source for the analogies in Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm and Luke’s Man With Edema may seem appealing, it must be noted that the analogy in Man With Edema is specifically tailored to the situation it addresses. The point of comparison is the threat to life from water. The son (and/or the ox) in the cistern is imperiled by an external threat, the danger of drowning, while the man with edema is imperiled by an internal threat: the fluids building up in his body could cause him to die suddenly.[16] The analogy in Daughter of Avraham is also tailored to its situation. The donkey and the ox have been tied up, while the woman has been bound by Satan. Below we will argue that the analogy about the sheep in the pit was likewise specifically tailored for the argument in Man’s Contractured Arm. Jesus appears to toy with the concept of קִיּוּם נֶפֶשׁ (qiyūm nefesh, “preserving a life”) and its vocabulary in his discussion of healing on the Sabbath. Since it is Hebrew concepts and terminology that give the argument and the pericope its unity, it is unlikely that the author of Matthew secondarily imported the analogy into Man’s Contractured Arm. Rather, we suspect that FR’s version of the pericope omitted the analogy, which explains its absence from the Lukan and Markan versions of the pericope, and that the author of Matthew “restored” the analogy to its proper place as he blended the versions of Man’s Contractured Arm he found in Mark and Anth.[17]

Crucial Issues

- From what condition did the man suffer?

- Is Matthew’s analogy about the sheep in the pit an original part of the story?

- Did Jesus break the Sabbath by healing the man’s hand/arm?

Comment

L1 καὶ ἐγένετο (GR). The structure of Luke’s opening to Man’s Contractured Arm (ἐγένετο + time marker) begins in a fairly Hebraic manner. The use in L3 of an infinitive as the main verb of the structure, on the other hand, is un-Hebraic. This structure with the infinitive never occurs in LXX,[18] but it does mimic normal Greek usage.[19] Moreover, ἐγένετο δὲ + time marker + infinitive also occurs in Lord of Shabbat (Luke 6:1) and Choosing the Twelve (Luke 6:12), the pericopae on either side of Man’s Contractured Arm. Since all three pericopae in which this construction occurs in Luke were probably based on FR, it is likely that the First Reconstructor was responsible for the presence of this hybrid Hebraic-Greek construction. The First Reconstructor probably adapted a Hebraic καὶ ἐγένετο/ἐγένετο δὲ + time marker + finite verb construction in Anth.’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm into a more acceptable ἐγένετο δὲ + time marker + infinitive construction. To reflect this likelihood we have adopted καὶ ἐγένετο (kai egeneto, “and it was”) for GR. The καί (kai, “and”) that opens the Markan and Matthean versions of Man’s Contractured Arm may reflect Anth.’s opening καί from a distance.

וַיְהִי (HR). On reconstructing γίνεσθαι (ginesthai, “to be”) with הָיָה (hāyāh, “be”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L1.

L2 ἐν τῷ σαββάτῳ (GR). Although Luke’s time marker, ἐν ἑτέρῳ σαββάτῳ (en heterō sabbatō, “in another Sabbath”), can be easily reconstructed as בְּשַׁבָּת אַחֶרֶת (beshabāt ’aḥeret, “in another Sabbath”),[20] we suspect that it was the First Reconstructor who added ἑτέρῳ (heterō, “another”) to the narrative. According to Lindsey, it was the First Reconstructor who attempted to make a continuous narrative out of Anth.’s reorganized text, so it was probably the First Reconstructor who added ἑτέρῳ in L2 in order to give readers a sense of narrative progression. Had ἑτέρῳ been present in Anth., we think it is unlikely that the author of Matthew would have contradicted his source by making Man’s Contractured Arm take place on the same day as Lord of Shabbat. If the First Reconstructor inserted ἑτέρῳ, Anth. probably read ἐν τῷ σαββάτῳ (en tō sabbatō, “on the Sabbath”), which is the phrase we have adopted for GR.

בַּשַׁבָּת (HR). On reconstructing σάββατον (sabbaton, “Sabbath”) with שַׁבָּת (shabāt, “Sabbath”), see Teaching in Kefar Nahum, Comment to L21.

L3 μεταβὰς ἐκεῖθεν ἦλθεν (Matt. 12:9). By writing μεταβὰς ἐκεῖθεν ἦλθεν (metabas ekeithen ēlthen, “going down from there he came”) the author of Matthew tied Man’s Contractured Arm more closely to the events described in Lord of Shabbat than did the Gospels of Luke or Mark. For Matthew, these events definitely took place on the same day.[21] Such narrative tightening looks redactional, and this appearance is confirmed by the author of Matthew’s use in L3 of distinctly Matthean vocabulary (μεταβαίνειν [metabainein, “to depart”];[22] ἐκεῖθεν [ekeithen, “from there”][23] ).[24]

καὶ εἰσῆλθεν (GR). As we noted above in Comment to L1, Luke’s infinitive in L3 is probably a concession to Greek style introduced by the First Reconstructor. In Anth. there was probably a third-person aorist verb, just as we find in Mark 3:1. Mark’s πάλιν (palin, “again”), on the other hand, is a redactional addition[25] which strengthens the connection between Man’s Contractured Arm and the preceding narrative (Lord of Shabbat). Lindsey identified πάλιν as a Markan stereotype.[26]

וַיִּכָּנֵס (HR). On reconstructing εἰσέρχεσθαι (eiserchesthai, “to enter”) with נִכְנַס (nichnas, “enter”), see Shimon’s Mother-in-law, Comment to L5.

L4 εἰς τὴν συναγωγὴν αὐτῶν (Matt. 12:9). By attaching the possessive pronoun αὐτῶν (avtōn, “of them”) the author of Matthew may have intended to indicate that the synagogue Jesus entered was the synagogue of the Pharisees who questioned the behavior of the disciples in Lord of Shabbat.[27] However, the addition of possessive pronouns (“yours,” “their”) to Jewish religious institutions is typical of Matthean redaction[28] and implies a desire on the part of the evangelist and his audience to disassociate from Jews and Judaism.[29] So the author of Matthew’s addition of αὐτῶν served the dual purposes of creating narrative continuity and social distancing. The omission of the possessive pronoun in Luke and Mark evinces a more neutral attitude toward the synagogue and undoubtedly reflects the language of the pre-synoptic tradition. After all, the authors of Luke and Mark would have had no reason to omit the pronoun had it occurred in their respective sources.[30]

εἰς τὴν συναγωγὴν (GR). A textual variant in Mark raises some uncertainty regarding GR in L4. Some manuscripts (like Codex Vaticanus) omit a definite article before συναγωγήν (sūnagōgēn, “synagogue”), while others include it. Scholars differ whether scribes added the article to assimilate Mark’s text to Luke’s and Matthew’s[31] or whether copyists omitted the article either out of carelessness or to avoid having to determine which synagogue was meant.[32] The Lukan-Matthean agreement to include the definite article might seem to settle the issue with regard to GR, but the author of Matthew would probably have added τήν (tēn, “the”) to συναγωγήν (sūnagōgēn, “synagogue”) when he attached the possessive pronoun after it, so in this instance the Lukan-Matthean agreement is not as potent an argument as usual. The question, therefore, comes down to whether the author of Luke or the First Reconstructor would have added the definite article if it had been absent in Anth. We do not see any reason why they would, so we have accepted Luke’s wording in L4 for GR.

לְבֵית הַכְּנֶסֶת (HR). On reconstructing συναγωγή (sūnagōgē, “synagogue”) as בֵּית כְּנֶסֶת (bēt keneset, “house of assembly,” “synagogue”), see Teaching in Kefar Nahum, Comment to L36.

L5 καὶ διδάσκειν (Luke 6:6). We suspect that “and to teach” is a redactional insertion of the author of Luke or the First Reconstructor,[33] probably intended to enhance Jesus’ image as an authoritative and admired teacher. The alternative is to suppose that Anth. included a separate sentence such as καὶ ἐδίδαξεν αὐτούς (kai edidaxen avtous, “and he taught them”), which the First Reconstructor abbreviated as καὶ διδάσκειν (kai didaskein, “and to teach”), but since no trace of the teaching motif surfaces in the Markan or Matthean parallels, we think this is unlikely. We have therefore omitted anything corresponding to Luke’s wording in L5 from GR and HR.

L6 καὶ ἰδοὺ ἄνθρωπος (GR). Compared to the wording in Luke and Mark, Matthew’s wording in L6 is strikingly Hebraic. We suspect that Luke’s wording, which the author of Mark copied, was FR’s stylistically improved paraphrase of Anth.’s wording, which Matthew reproduces in L6. Both the author of Luke and the First Reconstructor had a tendency to avoid ἰδού (idou, “behold!”).[34]

וְהִנֵּה אָדָם (HR). On reconstructing ἰδού (idou, “behold!”) with הִנֵּה (hinēh, “behold!”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L6.

In L6 ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos, “person,” “human”) could be reconstructed either with אָדָם (’ādām, “person,” “human”) or with אִישׁ (’ish, “man,” “adult male”).[35] We have preferred אָדָם because it is the man’s humanity, not his gender, that is at issue in the story, and also because אָדָם (“human”) makes for a better contrast with “sheep” in Matthew’s analogy, which we believe he copied from Anth.

On reconstructing ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos, “person,” “human”) with אָדָם (’ādām, “person,” “human”), see Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, Comment to L12.

L7 καὶ ἡ χεὶρ αὐτοῦ ἡ δεξιὰ ἦν ξηρά (GR). In L7 there is minimal verbal agreement between Luke, Mark and Matthew. Of the three, Mark’s wording is the most resistant to Hebrew retroversion,[36] and it appears to have been picked up from Luke’s wording in L15. There, Luke’s wording is probably redactional, since it reintroduces the man after the editorial explanations that the scribes and Pharisees were scrutinizing Jesus’ behavior in order to find grounds for an accusation against him and that Jesus was aware of their thoughts. Matthew’s wording also resists Hebrew retroversion,[37] but the agreement with Luke to use the adjective ξηρός (xēros, “dry”) against Mark’s participial form of ξηραίνειν (xērainein, “to dry up”) is important,[38] since such Lukan-Matthean agreements usually point to the wording of Anth. Indeed, Luke’s wording in L7 reverts quite easily to Hebrew and is, in our opinion, most likely to reflect Anth.’s wording (via FR). Matthew’s phrase χεῖρα ἔχων ξηράν (cheira echōn xēran, “having a dry hand”) is best explained as an attempt to blend the descriptions of the man in Anth. and Mark.[39]

יְמִינוֹ יְבֵשָׁה (HR). Our Hebrew reconstruction does not exactly replicate Luke’s Greek wording. On the other hand, Luke’s wording does resemble the way a Greek translator might render our Hebrew phrase. Hebrew possessed a noun, יָמִין (yāmin), for the right hand, but Greek (like English) did not have such a noun,[40] and so the LXX translators, when confronted by יָמִין + pronominal suffix, would sometimes resort to using the noun χείρ (cheir, “hand”) modified by the adjective δεξιός (dexios, “right”), as we can see in the following examples:

וַיִּשְׁלַח יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת יְמִינוֹ

And Israel [i.e., Jacob—JNT and DNB] stretched out his right hand. (Gen. 48:14)

ἐκτείνας δὲ Ισραηλ τὴν χεῖρα τὴν δεξιὰν

But Israel, stretching out the right hand…. (Gen. 48:14)

יְמִינְךָ יי תִּרְעַץ אוֹיֵב

Your right hand [יְמִינְךָ], O Lord, shatters the enemy. (Exod. 15:6)

ἡ δεξιά σου χείρ, κύριε, ἔθραυσεν ἐχθρούς.

Your right hand [ἡ δεξιά σου χείρ], O Lord, shattered the enemy. (Exod. 15:6)

Thus, ἡ χεὶρ αὐτοῦ ἡ δεξιά (hē cheir avtou hē dexia, “the hand of him, the right one”), the phrase we encounter in Luke’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm, would be a reasonable translation of יְמִינוֹ (yeminō, “his right hand”).

Our Hebrew reconstruction also differs from Luke’s Greek in that it lacks a conjunction equivalent to καί (kai, “and”) and a “to be” verb equivalent to ἦν (ēn, “was being”). We suspect these words were supplied by the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua, just as they were in the following example:

וְהִנֵּה אִישׁ מַרְאֵהוּ כְּמַרְאֵה נְחֹשֶׁת וּפְתִיל פִּשְׁתִּים בְּיָדוֹ

And behold! A man! His appearance like the appearance of bronze, and a thread of linen in his hand! (Ezek. 40:3)

καὶ ἰδοὺ ἀνήρ, καὶ ἡ ὅρασις αὐτοῦ ἦν ὡσεὶ ὅρασις χαλκοῦ στίλβοντος, καὶ ἐν τῇ χειρὶ αὐτοῦ ἦν σπαρτίον οἰκοδόμων

And behold! A man, and [καὶ] his appearance was [ἦν] like the appearance of shining bronze, and in his hand was [ἦν] a builder’s line. (Ezek. 40:3)

In LXX ξηρός (xēros, “dry”) does not often occur as an adjective. More frequently we find substantival uses, viz. ἡ ξηρά (hē xēra, “the dry land”) and τὸ ξηρόν (to xēron, “the dry ground”).[41] When ξηρός is used adjectivally, it most often occurs as the translation of the adjective יָבֵשׁ (yāvēsh, “dry”).[42] Although Hebrew has alternative adjectives for “dry,” יָבֵשׁ appears to be the best option for HR. In 1 Kings we read of a man’s “hand” that becomes “dry,” where “dry” is expressed with the cognate verb יָבֵשׁ (yāvēsh, “be dry”):

וַיְהִי כִשְׁמֹעַ הַמֶּלֶךְ אֶת־דְּבַר אִישׁ הָאֱלֹהִים אֲשֶׁר קָרָא עַל־הַמִּזְבֵּחַ בְּבֵית אֵל וַיִּשְׁלַח יָרָבְעָם אֶת־יָדוֹ מֵעַל הַמִּזְבֵּחַ לֵאמֹר תִּפְשֻׂהוּ וַתִּיבַשׁ יָדוֹ אֲשֶׁר שָׁלַח עָלָיו וְלֹא יָכֹל לַהֲשִׁיבָהּ אֵלָיו

And when the king heard the word of the man of God which he proclaimed against the altar in Bethel, Jeroboam stretched out his hand from upon the altar saying, “Seize him!” And his hand, which he stretched out against him, dried up [וַתִּיבַשׁ], and he was not able to bring it back toward himself. (1 Kgs. 13:4)

Likewise, in rabbinic literature we learn of a priest whose arm became “dry”:

מעשה באחד שיבשה זרועו ולא הניחה לקיים מה שנא′ ברך ה′ חילו ופועל ידיו תרצה

An anecdote concerning one [i.e., a priest who was offering incense—JNT and DNB] whose arm dried up [שֶׁיָּבְשָׁה זְרוֹעוֹ], but he did not stop it [i.e., the incense offering] in order to fulfill what is said, Bless, O Lord, his strength, and accept the work of his hands [Deut. 33:11]. (y. Yom. 2:3 [12b])

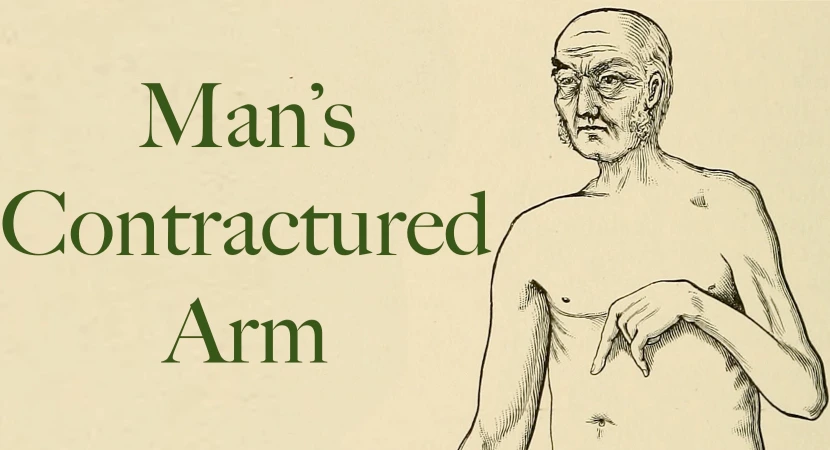

These examples not only demonstrate that the adjective יָבֵשׁ (yāvēsh, “dry”) is the best option for HR, they also provide insight into what sort of condition a “dry” limb implies.[43] First, in both instances it was not merely the hand but the entire arm that was affected. Hence, Jeroboam was not able to retract his outstretched hand. Since in Greek and Hebrew “hand” can be used pars pro toto for the entire arm,[44] it is probably best to conclude that, like these other cases of “dry” limbs, the condition the man in the synagogue suffered affected his entire arm.[45] Second, we also learn from the examples of Jeroboam and the priest that the drying up of a limb results in immobility. While the context allows for the understanding that the priest’s arm merely went limp, “dry” seems to imply stiffness rather than laxity, and we know that King Jeroboam’s arm froze in place. Likewise, the man in the synagogue probably had an arm that was not merely useless but also inflexible. His arm was probably locked in place.[46] Third, the drying up of Jeroboam’s hand and the priest’s arm came on quite suddenly, each as they were carrying out other activities. King Jeroboam was in the act of making a gesture when his arm became inflexible. Similarly, the priest was in the act of offering incense when he suddenly lost the use of his arm. So in our pericope “dried” or “withered,” if taken to refer to a stunted limb that had never properly developed, probably does not give an accurate picture of the man’s condition.[47] As in the other two cases of a “dried” arm, the likeliest scenario is that the man in our pericope suddenly lost the use of what had been a healthy limb.

In the story of Jeroboam the sudden stiffening of his arm is a divine judgment, but in the second account the paralysis of the priest’s arm was probably due to natural causes. What those natural causes might have been can only be guessed at. Possibly some kind of neurological issue, such as a stroke, was at the root of the problem. King Jeroboam’s paralyzed arm was healed within moments, and we are not told what became of the poor priest who valiantly completed his service despite his sudden impediment. But if the paralysis did not abate, then over time the muscles in his arm would have atrophied. His shortened muscles would then cause the limb to curl at the joints (shoulder, elbow, wrists, and fingers), a condition referred to as “contracture.” Such contracture is not merely awkward and uncomfortable, it can cause muscle pain in the rest of the body, which the contracture has put out of alignment. In addition, the curled-in fingers can cause infection if the nails of the fingers that cannot be straightened continue to grow and begin to cut into the palm of the hand.

The man in the synagogue may have suffered from just such a condition. The story does not tell us how long the “dryness” in his arm had persisted. If it was a recent development, then contracture may not yet have set in. But if the “dryness” of his arm was prolonged, then contracture was almost inevitable. In which case, the contracture of his arm into an unnatural shape would likely have caused the man considerable, and possibly unrelenting, pain. Whether or not contracture had begun, the ability of the man to perform manual labor would have been extremely limited. So, unless he happened to be extremely wealthy, his resources would have been severely taxed. If his suffering had lasted for more than a brief period, he was likely teetering on the edge of destitution, if, indeed, he had not fallen into penury already. And since his “dry” arm was merely a symptom of an unknown condition, whatever had caused his arm to become immobile might strike again at any moment, this time with even more catastrophic results. Thus, it does not do justice to our pericope to downplay the seriousness of the condition from which the man in the synagogue suffered.[48] An appreciation for the precariousness of the man’s condition is essential for putting the issue of healing on the Sabbath into proper perspective.

L8 παρετηροῦντο δὲ αὐτὸν (Luke 6:7). The phrase “but they were scrutinizing him” in L8 introduces a note of tension into the narrative. Scrutiny in itself need not be interpreted as hostile,[49] although L12 informs us that this particular scrutiny was done with malicious intent. In any case, the motif of scrutiny and the use of the verb παρατηρεῖν (paratērein, “to scrutinize,” “to closely examine”) to express the same are strongly correlated with pericopae the author of Luke copied from FR, occurring not only in Man’s Contractured Arm (Luke 6:7) but also in Man With Edema (Luke 14:1) and Tribute to Caesar (Luke 20:20). Moreover, we never find this scrutiny motif in pericopae stemming from Anth. So it is likely that the scrutiny motif is a redactional theme the First Reconstructor introduced into certain pericopae, and that παρατηρεῖν should therefore be regarded as a marker of FR redaction.[50] Since we regard the scrutiny motif as a redactional element in Man’s Contractured Arm, we have excluded Luke’s wording, which Mark accepted with minimal adjustment, from GR.[51]

καὶ ἐπηρώτησαν αὐτὸν (GR). In contrast to the note of tension that the scrutiny motif brings into the pericope, Matthew’s description of bystanders asking for Jesus’ opinion regarding the permissibility of healing on the Sabbath is blandly neutral (absent the purpose clause in L12). Matthew’s wording in L8 also reverts smoothly into Hebrew. On the basis of these observations we believe that in L8 Matthew preserves Anth.’s wording, which had been erased in the Lukan and Markan versions of the pericope on account of FR’s redactional activity. We have therefore accepted Matthew’s wording in L8 for GR.[52]

וַיִּשְׁאָלוּהוּ (HR). On reconstructing ἐπερωτᾶν (eperōtan, “to ask”) with שָׁאַל (shā’al, “ask”), see Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L5-6.

L9 λέγοντες (GR). Only Luke’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm identifies Jesus’ antagonists as “the scribes and the Pharisees.” Later in the narrative (L45-47) Mark’s version will identify Jesus’ adversaries as the Pharisees and the Herodians (Mark 3:6), while Matthew’s parallel (L45) will refer to the Pharisees alone (Matt. 12:14). Several arguments could be adduced in favor of viewing Luke’s reference to the scribes and Pharisees as original. First, the Pharisees play a role in two other Sabbath controversies (Lord of Shabbat, Man with Edema), so their presence in Man’s Contractured Arm is unremarkable and even expected. Second, the response to Jesus at the end of Luke’s version of the pericope is a typically Pharisaic response. The Pharisees discuss what they might “do with Jesus,” just as the Pharisaic leader Shimon ben Shetaḥ asked of Ḥoni, “What can I do with you?” (see the Conjectured Stages of Transmission discussion above). Third, one might suppose that the Pharisees were more likely to be interested in halakhic issues than “ordinary” Jews, so it seems natural in Man’s Contractured Arm to find the Pharisees expressing curiosity about Jesus’ Sabbath observance. Fourth, Jesus’ analogy concerning the sheep fallen into a pit appears designed to elicit assent from an audience that follows Pharisaic-rabbinic halakhah. Whereas sectarians from Qumran would not have accepted the premise of Jesus’ argument, a Pharisaic-rabbinic audience probably would, so a reference to the Pharisees in Man’s Contractured Arm appears to agree with the strategy Jesus adopted to defend his position regarding healing on the Sabbath.

But despite these arguments, we are inclined to agree with Flusser’s view that the earliest pre-synoptic version of Man’s Contractured Arm did not identify any specific opponents; there was merely curiosity among the synagogue attendees regarding Jesus’ view of healing on the Sabbath.[53] Not only does the lack of synoptic agreement regarding the inquirers’ identity support this view, but the First Reconstructor had a tendency to portray the Pharisees in a bad light, as malicious observers who scrutinized Jesus’ every action and examined his every word in order to find fault with his deeds or to trap him in something he said (see above, Comment to L8, and see below, Comment to L12). Moreover, the arguments in favor of Luke’s identification are not as strong as they might seem. For instance, one might suppose that the First Reconstructor added the reference to the Pharisees precisely in order to make Man’s Contractured Arm more similar to other Sabbath controversy stories. Likewise, although it is true that the Pharisees were interested in matters of halakhah, such interest was not theirs exclusively. Sabbath observance was common among all first-century Jews, so it would not be unexpected for “ordinary” Jews to ask Jesus his opinion on whether or not healing on the Sabbath was permitted. And although Jesus’ argument presumes his audience’s agreement with the opinions of the Pharisees, this may simply reflect the fact that the Pharisees’ opinions tended to agree with those of the people at large. It was the Qumran sectarians whose practice was both extreme and aberrant. The practice of the Pharisees was both more moderate and more mainstream.

If Mark’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm is based on Luke’s, why did he omit the reference to the scribes and Pharisees in L9?[54] Perhaps because by doing so the author of Mark drew Lord of Shabbat and Man’s Contractured Arm more tightly together. By omitting the subject in L9 (“the scribes and the Pharisees”), the antecedent of “they were scrutinizing” in L8 becomes οἱ Φαρισαῖοι (hoi Pharisaioi, “the Pharisees”) mentioned in Mark 2:24.[55] Not only does Mark’s omission of Luke’s subjects in L9 cause the verb in L8 to link back to Lord of Shabbat, it erases the change in the cast of characters in Luke (“some of the Pharisees” in Lord of Shabbat; “the scribes and the Pharisees” in Man’s Contractured Arm), which, as we discussed in the Story Placement discussion above, is one indication that the two narratives did not originally belong together.

The author of Matthew, following Mark, did not find a reference in L9 to the scribes and Pharisees in either of his sources, so it is not surprising that he did not supply such a reference on his own. In any case, such an identification in Matthew would have been redundant because the questioners’ identity as “the Pharisees” had already been implied by the author of Matthew’s addition of the pronoun αὐτῶν (avtōn, “their”) in L4. Matthew’s Hebraic λέγοντες (legontes, “saying”) in L9 probably reflects the wording of Anth. Thus, we have accepted λέγοντες for GR.

לֵאמֹר (HR). On reconstructing λέγειν (legein, “to say”) with אָמַר (’āmar, “say”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L15. We have reconstructed using the Biblical Hebrew form לֵאמֹר (lē’mor, “to say”) rather than the Mishnaic form לוֹמַר (lōmar, “to say”) because we prefer to reconstruct narrative (as opposed to direct speech) in a biblicizing style of Hebrew.[56]

L10 εἰ ἐν τῷ σαββάτῳ (Luke 6:7). As we discussed above in Comment to L8, the First Reconstructor replaced Anth.’s neutral questioning of Jesus’ opinion with malicious scrutiny of Jesus’ behavior. This tendentious adaptation required the First Reconstructor to change “Is it permissible on the Sabbath to heal?” in L10-11 to “…whether on the Sabbath he heals.” Luke reflects the First Reconstructor’s redaction, which the author of Mark accepted from Luke with minor modifications. In L10 these modifications include the omission of the preposition ἐν (en, “in”) and changing Luke’s singular τῷ σαββάτῳ (tō sabbatō, “[to] the Sabbath”) to the plural τοῖς σάββασιν (tois sabbasin, “[to] the Sabbaths”). The latter change was probably inspired by Luke’s use of τοῖς σάββασιν in Lord of Shabbat (Luke 6:2).[57]

εἰ ἔξεστιν ἐν τῷ σαββάτῳ (GR). Although we believe that in Anth.’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm a question about Sabbath observance was put to Jesus, we think it is likely that the author of Matthew continued his usual practice of blending the wording of his two sources, Mark and Anth., with the result that Matthew’s wording in L10 does not preserve Anth.’s precise wording. Matthew’s εἰ ἔξεστιν (ei exestin, “Is it permissible?”) probably came from Anth., but τοῖς σάββασιν probably comes from Mark,[58] whereas Anth. likely read ἐν τῷ σαββάτῳ (en tō sabbatō, “on the Sabbath”), which is more Hebraic.[59]

הֲיֵשׁ בַּשַּׁבָּת (HR). Although we often reconstruct εἰ (ei, “if”) with אִם (’im, “if”),[60] here we believe the interrogative -ה is a more appropriate reconstruction. Elsewhere we have reconstructed ἔξεστιν + infinitive with יֵשׁ + infinitive (Man With Edema, L10), and this seems the best reconstruction in L10 also, but examples of אִם יֵשׁ (’im yēsh, “if there is”) in direct questions are scarce in the Hebrew Scriptures, whereas הֲיֵשׁ (hayēsh, “Is there…?”) in direct questions is quite common. Moreover, the LXX translators tended to translate the interrogative -ה of הֲיֵשׁ as εἰ (ei, “if”), as we see in the following examples:

הֲיֵשׁ בֵּית אָבִיךְ מָקוֹם לָנוּ לָלִין

Is there [הֲיֵשׁ] in your father’s house a place for us to spend the night? (Gen. 24:23)

εἰ ἔστιν παρὰ τῷ πατρί σου τόπος ἡμῖν καταλῦσαι

If there is [εἰ ἔστιν] with your father a place for us to spend the night? (Gen. 24:23)

הֲיֵשׁ לָכֶם אָח

Is there [הֲיֵשׁ] to you a brother? (Gen. 43:7)

εἰ ἔστιν ὑμῖν ἀδελφός

If there is [εἰ ἔστιν] to you a brother? (Gen. 43:7)

הֲיֵשׁ אֱלוֹהַּ מִבַּלְעָדַי

Is there [הֲיֵשׁ] a god besides me? (Isa. 44:8)

εἰ ἔστιν θεὸς πλὴν ἐμοῦ

If there is [εἰ ἔστιν] a god besides me? (Isa. 44:8)[61]

In the examples cited above הֲיֵשׁ is followed by a noun (“Is there such-and-such a thing?”). In our reconstruction we have הֲיֵשׁ followed by an infinitive to express “Is there an obligation to do such-and-such a thing?” We find a similar usage in the following verse:

הֲיֵשׁ לְדַבֶּר לָךְ אֶל הַמֶּלֶךְ

Should we speak for you to the king? (2 Kgs. 4:13)

This example shows that הֲיֵשׁ + infinitive, as in our reconstruction, is not foreign to Hebrew.

On reconstructing ἔξεστιν + infinitive with יֵשׁ + infinitive, see Man With Edema, Comment to L10.

On reconstructing σάββατον (sabbaton, “Sabbath”) with שַׁבָּת (shabāt, “Sabbath”), see above, Comment to L2.

L11 θεραπεῦσαι (GR). All three evangelists agree to use the verb θεραπεύειν (therapevein, “to give medical treatment,” “to heal”) in L11. There is some textual uncertainty whether Luke used the future tense θεραπεύσει (therapevsei, “he will heal”) as in Codex Vaticanus, which serves as the base text for our reconstruction document, or θεραπεύει (therapevei, “he heals”), the reading adopted by Nestle-Aland. Likewise, whereas Codex Vaticanus has θεραπεύειν in Matthew, N‑A has θεραπεῦσαι (therapevsai, “to give medical treatment,” “to heal”). Mark uses the future tense and adds αὐτόν (avton, “him”), making the scrutiny more focused on whether Jesus will heal the man with the contractured arm. It is odd that Luke’s version lacks the direct object “him,” but the absence of the pronoun in Luke is supported by the lack of αὐτόν in Matthew’s parallel. Thus, the absence of αὐτόν in Luke may be the result of the First Reconstructor’s conservative redaction. Despite transforming Anth.’s question (“Is it allowed on the Sabbath to heal?”) into a conditional clause (“whether on the Sabbath he heals”), the First Reconstructor changed as few words as possible, even though this gave the clause a lack of focus. The αὐτόν in Mark should thus be regarded as a stylistic improvement. In any case, we regard Matthew’s interrogative as original (see above, Comment to L8) and have therefore accepted Matthew’s infinitive for GR.

לְרַפְּאוֹת (HR). On reconstructing θεραπεύειν (therapevein, “to give medical treatment,” “to heal”) with רִפֵּא (ripē’, “give medical treatment,” “heal”), see Sending the Twelve: Commissioning, Comment to L22-23. For HR we have adopted the Mishnaic Hebrew form of the infinitive, since this is the style of Hebrew we prefer when reconstructing direct speech.

The question of what may or may not be done for a sick or injured person on the Sabbath was still hotly debated in the first century. Some Jews adopted a stringent view on the matter, and others took a more lenient approach. The synagogue attendees in Man’s Contractured Arm wanted to know Jesus’ opinion on this matter in order to ascertain where he fell on the religious ideological spectrum. Jesus must have been puzzling to his contemporaries, since on some issues, such as monogamy and divorce, Jesus was far more stringent than the Pharisees, whereas on other issues, such as ritual purity, he seemed far more relaxed. Despite what may have appeared to some as halakhic eccentricity, there was an inner consistency to Jesus’ approach. Regarding interpersonal relationships Jesus prioritized love of one’s companion, which translated into strict rulings on issues of marriage and divorce. But regarding the human-divine relationship Jesus prioritized human welfare over divine prerogatives, which translated into relaxing the rigors of ritual purity and Sabbath observance for the sake of alleviating human suffering.

L12 ἵνα εὕρωσιν κατηγορεῖν αὐτοῦ (Luke 6:7). Although the verb κατηγορεῖν (katēgorein, “to accuse”) occurs more often in Luke (4xx) than in Mark (3xx) or Matthew (2xx), and although κατηγορεῖν occurs 9xx in Acts, all of which are in the second half, where Luke’s personal linguistic preferences are most evident,[62] we attribute Luke’s wording in L12 to FR rather than to Lukan redaction. Our reason is that clauses ascribing malicious motives to those who question or observe Jesus is a motif that occurs in two other FR pericopae. At the conclusion of Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees we read that the scribes and the Pharisees were laying in wait for Jesus θηρεῦσαί τι ἐκ τοῦ στόματος αὐτοῦ (thērevsai ti ek tou stomatos avtou, “to catch him in something from his mouth [i.e., in something objectionable Jesus might say]”; Luke 11:54). Likewise, in Tribute to Caesar the scribes and the chief priests scrutinized Jesus ἵνα ἐπιλάβωνται αὐτοῦ λόγου (hina epilabōntai avtou logou, “in order to catch him by his speech”; Luke 20:20). The First Reconstructor’s use of “Lukan” vocabulary is explained by the subject matter. The protagonists of both FR (Jesus) and Acts (Paul) are wrongly accused before the authorities.

Fitzmyer regarded Luke’s wording in L12 as a revision of Mark’s parallel, but explained Luke’s εὑρίσκειν + no object + infinitive construction (ἵνα εὕρωσιν κατηγορεῖν αὐτοῦ [hina hevrōsin katēgorein avtou, “in order that they might find ⟨grounds⟩ to accuse him”]) as an Aramaism.[63] But how the author of Luke could have produced an Aramiac construction if he was editing a Greek text is a mystery. Fitzmyer did not suggest, for instance, that the author of Luke worked from a source translated from Aramaic that paralleled Mark, or that occasionally the author of Luke’s mother tongue, Aramaic, colored his Greek. Not only is Fitzmyer’s Aramaic explanation mysterious, it turns out to be entirely unnecessary. Luke’s εὑρίσκειν + no object + infinitive construction is perfectly normal Koine Greek,[64] as we can see from comparable examples in the Discourses of Epictetus:

δὸς γοῦν ᾧ θέλεις ἡμῶν ἰδιώτην τινὰ τὸν προσδιαλεγόμενον· καὶ οὐχ εὑρίσκει χρήσασθαι αὐτῷ

At all events, give to any one of us you please some layman with whom to carry on an argument; he will not find [a way] to deal [εὑρίσκει χρήσασθαι] with him…. (Epictetus, Discourses 2:12 §2; Loeb [adapted])

πάλιν ἂν μὴ εὕρωμεν φαγεῖν ἐκ βαλανείου, οὐδέποθ’ ἡμῶν καταστέλλει τὴν ἐπιθυμίαν ὁ παιδαγωγός, ἀλλὰ δέρει τὸν μάγειρον

And again, if we when children don’t find [something] to eat [εὕρωμεν φαγεῖν] after our bath, our attendant never checks our appetite, but he cudgels the cook. (Epictetus, Discourses 3:19 §5; Loeb [adapted])

In contrast to Fitzmyer, we regard Mark’s wording in L12 as a streamlined paraphrase of the wording Luke had taken over from FR. To compensate for his omission of the scrutiny motif in L8, the author of Matthew accepted in L12 the purpose clause he read in Mark, even though it clashes with the innocent querying of Jesus’ opinion he took over from Anth. in L10-11. The result in Matthew is the bizarre portrayal of the Pharisees acting like the thought police, hoping to accuse Jesus because of the opinions he held rather than because of an action he might take. Such an unrealistic scenario shows that the desire to accuse Jesus originally belonged with the scrutiny of Jesus’ behavior, as we find it in Luke and Mark.[65]

L13 αὐτὸς δὲ ᾔδει τοὺς διαλογισμοὺς αὐτῶν (Luke 6:8). There are several reasons for regarding Luke’s notice in L13 about Jesus’ (supernatural?) awareness of his critics’ thoughts as redactional. First, Luke’s word order, with the subject (ἀυτός [avtos, “he”]) placed before the verb (ᾔδει [ēdei, “had known”]), is un-Hebraic. Second, sentences opening with αὐτὸς δέ are especially common in Lukan pericopae copied from FR.[66] Third, the noun διαλογισμός (dialogismos, “thought”) occurs with a higher frequency in Luke’s Gospel (6xx) compared to Mark (1x) and Matthew (1x).[67] Fourth, the majority of Luke’s instances of διαλογισμός occur in pericopae identified as stemming from FR (Bedridden Man [Luke 5:22]; Man’s Contractured Arm [Luke 6:8]; Greatness in the Kingdom of Heaven [Luke 9:46, 47]). Fifth, in Bedridden Man, Man’s Contractured Arm and Greatness in the Kingdom of Heaven διαλογισμός occurs in contexts describing Jesus’ uncanny perception of people’s thoughts: ἐπιγνοὺς δὲ ὁ Ἰησοῦς τοὺς διαλογισμοὺς αὐτῶν (epignous de ho Iēsous tous dialogismous avtōn, “But Jesus, knowing their thoughts…”; Luke 5:22), αὐτὸς δὲ ᾔδει τοὺς διαλογισμοὺς αὐτῶν (avtos de ēdei tous dialogismous avtōn, “but he knew their thoughts”; Luke 6:8), ὁ δὲ Ἰησοῦς εἰδὼς τὸν διαλογισμὸν τῆς καρδίας αὐτῶν (ho de Iēsous eidōs ton dialogismon tēs kardias avtōn, “But Jesus, knowing the thoughts of their hearts…”; Luke 9:47).[68] Thus, Jesus’ awareness of other people’s thoughts appears to be a redactional motif of the First Reconstructor. Attributing this motif as well as Luke’s use of διαλογισμός to FR in Man’s Contractured Arm is also supported by the complete absence of διαλογισμός in Acts.[69] Thus, διαλογισμός cannot be regarded as a Lukan word. It is a term the author of Luke took over from his source (FR).

It may seem surprising that the author of Mark omitted Luke’s notice about Jesus’ awareness of his critics’ thoughts, but this omission may be due to his preference for focusing on Jesus’ emotive response to his critics’ unwillingness to engage with his question (L36-39) rather than on Jesus’ supernatural awareness of their malign intentions even before the encounter began. The author of Matthew, working from Mark and Anth., had no knowledge of FR’s redactional motif in L13, so naturally it does not appear in Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm.

Since we attribute Luke’s wording in L13 to FR redaction, it has been excluded from GR and lacks an equivalent in HR.

L14-17 Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm lacks the description in L14-17 of Jesus’ summoning the afflicted man to center stage. The reason for this omission could be that the author of Matthew saw that this description was not present in Anth., and therefore he decided to skip over it when copying Mark. Or the description could have been present in Mark and Anth., but the author of Matthew skipped over it as non-essential. Such an omission would be consistent with the author of Matthew’s frequent economizing approach to his sources.[70] A decision is difficult, but we suspect that the economizing explanation is correct.

L14 καὶ εἶπεν τῷ ἀνθρώπῳ (GR). We believe Luke and Mark preserve Anth.’s wording, albeit in different ways. Luke’s use of the aorist εἶπεν (eipen, “he said”) is more Hebraic than Mark’s historical present λέγει (legei, “he says”). On the other hand, Mark’s use of the noun ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos, “person,” “human”) looks more original, whereas Luke’s use of ἀνήρ (anēr, “man”) may be a stylistic improvement. The reason ἄνθρωπος looks more original is that this is the noun all three evangelists used in L6 to refer to the man with the contractured arm. Moreover, it appears the author of Luke had a slight redactional preference for ἀνήρ over ἄνθρωπος.[71] When the author of Luke changed τῷ ἀνθρώπῳ (tō anthrōpō, “the person”) to τῷ ἀνδρί (tō andri, “to the man”), he could have easily changed καὶ εἶπεν (kai eipen, “and he said”) to εἶπεν δέ (eipen de, “but he said”), a minor stylistic improvement. Thus, for GR we have adopted the most Hebraic wording attested in Luke and Mark: καὶ εἶπεν τῷ ἀνθρώπῳ (kai eipen tō anthrōpō, “and he said to the person”).

וַיּאֹמֶר לָאָדָם (HR). On reconstructing εἰπεῖν (eipein, “to say”) with אָמַר (’āmar, “say”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L12.

On reconstructing ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos, “person,” “human”) with אָדָם (’ādām, “person,” “human”), see above, Comment to L6.

L15 τῷ ξηρὰν ἔχοντι τὴν χεῖρα (Luke 6:8). Luke’s wording in L15 resists retroversion to Hebrew. The word order is un-Hebraic, and it is impossible to express the idea without supplying additional words in Hebrew. For instance, Delitzsch translated Luke’s τῷ ἀνδρὶ τῷ ξηρὰν ἔχοντι τὴν χεῖρα (tō andri tō xēran echonti tēn cheira, “to the | man | the one | dry | having | the | hand”) as אֶל הָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר יָבְשָׁה יָדוֹ (’el hā’ish ’asher yāveshāh yādō, “to | the man | who | was dry | his hand”), a phrase we might have expected to be expressed in Greek as τῷ ἀνδρὶ οὗ ἐξηράνθη ἡ χεὶρ αὐτοῦ (tō andri hou exēranthē hē cheir avtou, “to the man of whom his hand dried up”). The author of Mark slightly rearranged Luke’s wording, but his Greek does not revert to Hebrew any more easily. Both Delitzsch and Lindsey, for instance, translated Mark’s τῷ ἀνθρώπῳ τῷ τὴν ξηρὰν χεῖρα ἔχοντι (tō anthrōpō tō tēn xēran cheira echonti, “to the | person | the one | the | dry | hand | having”) exactly as Delitzsch had translated Luke’s parallel.[72] The difficulty with which Luke’s Greek in L15 reverts to Hebrew suggests that it is redactional. We suspect the First Reconstructor added this description of the man because he found it necessary to reorient his readers to the situation in the narrative after his long insertions about the scrutiny of Jesus’ behavior (L8), the malicious intent of the scrutinizers (L12), and Jesus’ supernatural perception of the scrutinizers’ thoughts (L13). Since we regard the Lukan and Markan description of the man as redactional, we have excluded this description from GR and HR.

L16 ἔγειρε καὶ στῆθι εἰς τὸ μέσον (GR). In Luke, the wording of the command Jesus gives to the man to get up and stand in the middle reverts easily to Hebrew, and it does not bear the marks of Greek redaction. We have therefore accepted Luke’s wording in L16 for GR.

Apart from the omission of the second imperative (καὶ στῆθι [kai stēthi, “And stand!”]), Mark’s wording is identical to Luke’s. We can think of no particular reason why the author of Mark would have wanted to omit Luke’s second imperative, but in this pericope the author of Mark has eliminated several words and phrases found in the Lukan parallel (cf. L2, L9, L13, L17, L20).

קוּם וַעֲמֹד בַּתָּוֶךְ (HR). On reconstructing ἐγείρειν (egeirein, “to arise,” “to raise”) with קָם (qām, “arise”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L15.

On reconstructing ἑστάναι (hestanai, “to stand”) with עָמַד (‘āmad, “stand”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L14.

On reconstructing μέσος (mesos, “middle,” “among”) with תָּוֶךְ (tāvech, “middle,” “midst”), see “The Harvest Is Plentiful” and “A Flock Among Wolves,” Comment to L50. In the Hebrew Scriptures the phrase בַּתָּוֶךְ (batāvech, “in the middle”) occurs only 5xx (Gen. 15:10; Num. 35:5; Josh. 8:22; Judg. 15:4; Isa. 66:17). The LXX translators rendered these instances of בַּתָּוֶךְ in a variety of ways, but never as εἰς τὸ μέσον (eis to meson, “into the middle”). Nevertheless, we can think of no better option than בַּתָּוֶךְ for HR.

L17 καὶ ἐγερθεὶς ἔστη (GR). Although Luke’s wording in L17 reverts easily to Hebrew, we suspect that Luke’s use of the verb ἀναστῆναι (anastēnai, “to arise”) in L17, which contrasts with ἑστάναι (hestanai, “to stand”) in L16 (and cf. L28), comes from FR. The First Reconstructor probably chose a synonymous verb in L17 to avoid monotony. Elsewhere we have found ἀναστῆναι to be the product of FR redaction.[73] Therefore, we have adopted the phrase καὶ ἐγερθεὶς ἔστη (kai egertheis estē, “and rising, he stood”) for GR.

וַיָּקָם וַיַּעֲמֹד (HR). On reconstructing ἐγείρειν (egeirein, “to arise,” “to raise”) with קָם (qām, “arise”), and on reconstructing ἑστάναι (hestanai, “to stand”) with עָמַד (‘āmad, “stand”), see above, Comment to L16.

L18-19 εἶπεν δὲ πρὸς αὐτούς (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreement to use the aorist verb εἶπεν (eipen, “he said”) against Mark’s historical present tense verb λέγει (legei, “he speaks”) is more Hebraic and likely reflects the wording of Anth. Both Luke and Matthew also agree to use the conjunction δέ (de, “but”). Luke’s εἶπεν δέ (eipen de, “but he said”) is more Hebraic than Matthew’s ὁ δὲ εἶπεν (ho de eipen, “but he said”),[74] so we have adopted Luke’s phrase for GR.

Because we suspect that either the First Reconstructor or the author of Luke added Jesus’ name in L18 for the sake of clarity, we have omitted Jesus’ name from GR.

Both Luke’s πρὸς αὐτούς (pros avtous, “to them”) and the αὐτοῖς (avtois, “to them”) in Mark and Matthew revert easily to Hebrew. We have preferred Luke’s wording for GR on the supposition that the author of Matthew copied αὐτοῖς from Mark, which was more succinct than the πρὸς αὐτούς he saw in Anth.

וַיּאֹמֶר לָהֶם (HR). On reconstructing εἰπεῖν (eipein, “to say”) with אָמַר (’āmar, “say”), see above, Comment to L14.

L20-23 Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm omits the question about whether it is permitted to do good or evil, to save or destroy on the Sabbath. Once again, as in L14-17, we must ask ourselves whether the author of Matthew skipped over this question, which he knew from Mark, because it was absent in Anth.,[75] or whether the author of Matthew omitted this question even though it was present in both of his sources. We believe the latter is correct: the author of Matthew skipped over the question in L20-23, versions of which he found in Mark and Anth., because he intended to paraphrase it in L31, where the question would be transformed into the concluding statement of Jesus’ argument.[76] There is a clear literary motive for the author of Matthew to have done this. In Mark—and probably also in Anth.—Jesus does not answer his own questions. He leaves it to his audience to draw their own conclusions from the healing they witnessed. The author of Matthew, who could sometimes be pedantic, wanted Jesus to give an explicit verbal answer to the question the synagogue-goers posed in L10-11. Since his sources did not provide an answer, the author of Matthew formulated an answer by paraphrasing the original question.

Our reasons for suspecting that (at least parts of) the question in L20-23 were present in Anth. are twofold. First, Luke’s “to save or destroy a soul” (L23) appears to reflect a Hebrew idiom, which is an improbable phenomenon if the author of Luke or the First Reconstructor composed the question in Greek. Second, the Hebrew behind the verb “to save” in L23 appears to have been the same as that which stands behind Matthew’s ἐγείρειν (egeirein, “to raise up [from a lying position],” “to elevate”) in Matt. 12:11 (see below, Comment to L28). Thus, there emerges a verbal and conceptual unity between L20-23 and L24-30. That the verbal and conceptual unity is no longer apparent in Greek and that this unity can only be recovered from the combined witness of the Synoptic Gospels suggest that both L20-23 and L24-30 have their origin in Anth., the source that best preserved the Hebrew substratum beneath the synoptic tradition.

L20 ἐπερωτῶ ὑμᾶς (GR). Responding to a question with a counter-question is typical both of Jesus’ style and of ancient Jewish discourse generally. Since there was no reason for the author of Luke or the First Reconstructor to have added ἐπερωτῶ ὑμᾶς (eperōtō hūmas, “I ask you”), and since this phrase reverts easily to Hebrew, we have accepted Luke’s wording in L20 for GR.

אֲנִי שׁוֹאֵל אֶתְכֶם (HR). On reconstructing ἐπερωτᾶν (eperōtan, “to ask”) with שָׁאַל (shā’al, “ask”), see above, Comment to L8. Below we cite an example of the phrase אֲנִי שׁוֹאֵל אֶתְכֶם (’ani shō’ēl ’etchem, “I ask you”), which occurs in a story concerning the period of the Bar Kochva revolt:

אָמַר לָהֶם: שָׁלשׁ שְׁאֵלוֹת אֲנִי שׁוֹאֵל אֶתְכֶם, אִם הֲשִׁיבוֹתֶם לִי, הֲרֵי מוּטָב

He [i.e., a Roman soldier—JNT and DNB] said to them [i.e., to two disciples of Rabbi Yehoshua—JNT and DNB], “I will ask you [אֲנִי שׁוֹאֵל אֶתְכֶם] three questions. If you can answer me, good!” (Gen. Rab. 82:8 [ed. Merkin, 3:250])

L21 εἰ ἔξεστιν τῷ σαββάτῳ (GR). In L21 Jesus repeats the opening of the question posed to him in L10. As in L10, we have accepted Luke’s more Hebraic τῷ σαββάτῳ (tō sabbatō, “in the Sabbath [sing.]”) instead of Mark’s τοῖς σάββασιν (tois sabbasin, “in the Sabbaths [plur.]”).

הֲיֵשׁ בַּשַּׁבָּת (HR). On reconstructing ἔξεστιν + infinitive with יֵשׁ + infinitive, see above, Comment to L10.

On reconstructing σάββατον (sabbaton, “Sabbath”) with שַׁבָּת (shabāt, “Sabbath”), see above, Comment to L2.

L22 ἀγαθοποιῆσαι ἢ κακοποιῆσαι (Luke 6:9). The issue of doing good or doing evil is not really germane to the controversy, which has to do with the prohibition against work on the Sabbath. The real issues are 1) whether healing/giving medical treatment should be regarded as a kind of work, and 2) if they are work, whether healing/giving medical treatment should override the prohibitions of the Sabbath. By the first century, Jewish halakhah was generally agreed that measures taken to preserve the life of a person at risk of dying do indeed override the prohibitions against working on the Sabbath. How great a risk to a person’s life and how much could be done for a person at risk, on the other hand, were still topics of debate, both among the various sects and within the sects themselves. Doing good versus doing evil, on the other hand, goes far beyond the scope of debate. No one, of course, advocated doing evil on the Sabbath or on any other day of the week. And struggling to determine what constituted doing good was what the controversy was all about. As the rabbinic maxim stated, אֵין טוֹב אֶלָּא תּוֹרָה (’ēn ṭōv ’elā’ tōrāh, “There is no good other than Torah”; m. Avot 6:3; b. Ber. 5a). Since the Torah prescribed the prohibition of work on the Sabbath, observing those prohibitions must constitute doing good, unless there is a good that ought to be done which is greater than Sabbath observance. Whether there was such a greater good and, if so, what that greater good might be and how to define it—not the issue of doing good versus doing evil—is what is at stake in Man’s Contractured Arm.[77]

While the overgeneralized terms (doing good versus doing evil) are extraneous to the original debate, they could quite easily have been introduced by a later editor who wished to adapt the pericope for a Gentile or mixed Jewish-Gentile audience for whom the issue of Sabbath observance may have been less familiar and was certainly (at least for the Gentile segment of the audience) less relevant. The First Reconstructor was just such an editor, and attributing Luke’s wording in L22 to FR is supported by the fact that while the verb ἀγαθοποιεῖν (agathopoiein, “to do good”) occurs 4xx in Luke (always in FR pericopae), it never occurs in Acts.[78] This pattern of ἀγαθοποιεῖν in Luke suggests that the author of Luke was willing to use ἀγαθοποιεῖν when he encountered it in his source(s), but was not inclined to use this verb on his own.

Scholars occasionally point out that the verb ἀγαθοποιεῖν (“to do good”) does not occur in Classical Greek.[79] It is perfectly at home, however, in Koine Greek, being found in LXX,[80] Hellenistic Jewish literature,[81] NT epistles,[82] and early Christian sources.[83] In 1 Pet. 3:17 and 3 John 11 “doing good” is contrasted with “doing evil” using the same verbs we find in Luke 6:9. The verb κακοποιεῖν (kakopoiein, “to do bad”) does not occur elsewhere in Luke. Nevertheless, it is safe to conclude that both ἀγαθοποιεῖν and κακοποιεῖν belong to the First Reconstructor’s universalistic ethical vocabulary.[84]

L23 ζῳογονεῖν ψυχὴν ἢ ἀπολέσαι (GR). Our reconstruction of Anth.’s wording in L23 is identical to Luke except in two respects. First, we have adopted a more Hebraic word order by placing the accusative object (ψυχήν [psūchēn, “a soul”]) after the verb instead of in Luke’s emphatic position. Second, in place of the verb σώζειν (sōzein, “to save”) we have adopted the verb ζῳογονεῖν (zōogonein, “to make alive,” “to preserve alive”). This second change is not strictly necessary and would not affect our Hebrew reconstruction. Nevertheless, in Preserving and Destroying (L9) we encountered an instance where the First Reconstructor changed Anth.’s ζῳογονεῖν to σώζειν,[85] a verb that belonged to the First Reconstructor’s redactional vocabulary,[86] so it is reasonable to hypothesize that σώζειν in Man’s Contractured Arm (L23) is another instance where the First Reconstructor replaced Anth.’s ζῳογονεῖν with one of his preferred, and theologically pregnant, terms.

Mark’s wording in L23 is nearly identical to Luke’s except that in place of Luke’s ἀπολέσαι (apolesai, “to destroy”) Mark has ἀποκτεῖναι (apokteinai, “to kill”). Luke’s verb appears to reflect a Hebrew idiom that contrasts preserving and destroying a soul, an example of which is found in this famous rabbinic saying:

נִיבְרָא אָדָם יָחִיד בָּעוֹלָם לְלַמֵּד שֶׁכָּל הַמְאַבֵּד נֶפֶשׁ אַחַת מַעֲלִין עָלָיו כְּיִלּוּ אִבֵּד עוֹלָם מָלֵא וְכָל הַמְקַיֵּים נֶפֶשׁ אַחַת מַעְלִין עָלָיו כְּיִלּוּ קִיֵּים עוֹלָם מָלֵא

…Adam was created unique in the world, in order to teach that everyone who destroys [הַמְאַבֵּד] one soul [נֶפֶשׁ], they account it to him as though he had destroyed [אִבֵּד] an entire world, but everyone who preserves [הַמְקַיֵּים] one soul [נֶפֶשׁ], they account it to him as though he had kept [קִיֵּים] the entire world alive. (m. Sanh. 4:5)[87]

Mark’s “kill” in L23 is less Hebraic than Luke’s “destroy” and probably represents an interpretive paraphrase of the Hebraic expression preserved in Luke. In part, the author of Mark’s decision to write “kill” in L23 must have been influenced by his intention to replace Luke’s description of the people’s asking “what they might do with Jesus” (L51) with the Pharisees’ plotting with the Herodians “how they might destroy him.” It is quite possible that the author of Mark composed his Gospel for audiences that were familiar with Luke. If so, Mark’s audience would have been expecting to hear the word “destroy” in Jesus’ question and therefore would have taken note of “kill” in Mark’s paraphrase. When Mark subsequently used “destroy” at the conclusion of the pericope, they would have heard the resonance with Jesus’ question and made the equation in their minds that “destroy” means “kill.” The result for Mark’s audience would have been a heightened sense of irony: because Jesus advocated saving lives on the Sabbath, his enemies sought to kill him.[88]

לְקַיֵּם נֶפֶשׁ אוֹ לְאַבְּדָהּ (HR).[89] On reconstructing ζῳογονεῖν (zōogonein, “to make alive,” “to preserve alive”) with קִיֵּם (qiyēm, “preserve alive,” “keep alive”), see Preserving and Destroying, Comment to L9.

On reconstructing ψυχή (psūchē, “soul,” “self,” “life”) with נֶפֶשׁ (nefesh, “soul,” “self,” “life”), see Demands of Discipleship, Comment to L18.

On reconstructing ἤ (ē, “or”) with אוֹ (’ō, “or”), see Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry, Comment to L47.

On reconstructing ἀπολλύειν (apollūein, “to destroy”) with אִבֵּד (’ibēd, “destroy”), see Days of the Son of Man, Comment to L21. We noted above the Hebrew idiom that contrasts “preserving a life” and “destroying a life” with the verbs קִיֵּם (qiyēm, “preserve alive,” “keep alive”) and אִבֵּד (’ibēd, “destroy”).

In our reconstruction we have attached a pronominal suffix to אִבֵּד. Although no equivalent, such as αὐτήν (avtēn, “it”), is present in GR, it was not uncommon for Greek translators of Hebrew texts to omit an equivalent to pronominal suffixes.[90]

Our reconstructed phrase לְקַיֵּם נֶפֶשׁ (leqayēm nefesh, “to preserve a soul [i.e., life]”) belongs to the conceptual framework of קִיּוּם נֶפֶשׁ (qiyūm nefesh, lit. “preservation of a soul [i.e., life]”), namely, all that which pertains to sustaining life (e.g., the provision of food and clothing as well as emergency life-saving measures). The concept of qiyūm nefesh is broad, as it can be applied to any situation pertaining to preserving anything alive.[91] The concept is also quite ancient, as the vocabulary of qiyūm nefesh is attested in Second Temple sources (DSS). And the concept of qiyūm nefesh was shared across different streams of ancient Judaism; the vocabulary of qiyūm nefesh occurs in sectarian writings from Qumran as well as in rabbinic literature.

The concept of קִיּוּם נֶפֶשׁ (qiyūm nefesh, “sustaining a life”) is not to be confused with the narrower and more specific concept of פִּיקוּחַ נֶפֶשׁ (piqūaḥ nefesh), rescuing a human life on the Sabbath. The term piqūaḥ nefesh is first encountered in discussions dating from the period after the destruction of the Second Temple. And unlike qiyūm nefesh, the term piqūaḥ nefesh is peculiar to rabbinic discourse. Piqūaḥ nefesh literally means “digging out of a soul,”[92] and refers to the concrete situation of digging a person out of the rubble of a collapsed building on the Sabbath. This unfortunate scenario became an important test case in rabbinic discussions of which situations override the prohibitions of the Sabbath, and piqūaḥ nefesh eventually became shorthand for any and all situations that met the rabbinic standard for superseding the Sabbath.

Despite the differences between the concepts of qiyūm nefesh (that which is necessary to sustain life in general) and piqūaḥ nefesh (rescuing a person from a life-threatening situation on the Sabbath), a connection nevertheless exists between them. Kister drew attention to the fact that at a certain place in a rabbinic midrash where the term piqūaḥ nefesh occurs, qiyūm nefesh occurs in a genizah fragment as a textual variant.[93]

|

Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Shabbata §1 |

|

|

Standard Text (ed. Lauterbach, 2:493) |

Genizah Fragment with Textual Variant[94] |

|

מנין לפיקוח נפש שידחה את השבת…קל וחומר לפיקוח נפש שידחה את השבת |

מנין לקיום נפש שידחה את השבת… קול וחומ′ לקיום נפש שידחה את השבת |

|

How do we know that piqūaḥ nefesh overrides the Sabbath? …thus on the principle of kal vahomer we know that piqūaḥ nefesh overrides the Sabbath. |

How do we know that the necessity of preserving a life [qiyūm nefesh] overrides the Sabbath? …thus on the principle of kal vahomer we know that the necessity of preserving a life [qiyūm nefesh] overrides the Sabbath. |

As we have seen, the two terms are not quite interchangeable, but the textual variant above demonstrates that the more general term qiyūm nefesh was used at times, even in rabbinic discourse, where the technical term piqūaḥ nefesh might be expected. This is probably because qiyūm nefesh represents everyday speech, whereas piqūaḥ nefesh represents rabbinic jargon that was mostly confined to the bet midrash. In Jesus’ time the term piqūaḥ nefesh may not even have been coined, and yet Jesus’ position on qiyūm nefesh vis-à-vis the Sabbath can usefully be compared to rabbinic discussions of piqūaḥ nefesh, since the debate regarding how to balance the demands of Sabbath observance with the duty to preserve human life, which began in the Second Temple period, continued into, and is reflected in, rabbinic sources.[95]

To demonstrate the usefulness of rabbinic discussions of piqūaḥ nefesh for understanding Jesus’ stance regarding qiyūm nefesh we may compare the following argument advanced by Rabbi Shimon ben Menasya with the question Jesus poses in Man’s Contractured Arm:

רבי שמעון בן מנסיא אומר ויהא פקוח נפש דוחה את השבת והדין נותן אם דוחה רציחה את העבודה שהיא דוחה את השבת פקוח נפש שהוא דוחה את העבודה לא כל שכן

Rabbi Shimon ben Menasya says, “And let piqūaḥ nefesh override the Sabbath. And the reason given: If [the punishment of] murder [which is execution—JNT and DNB] overrides the divine service, which itself overrides the Sabbath, then should not piqūaḥ nefesh, which overrides the divine service, all the more [override the Sabbath]?” (Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Nezikin §4 [ed. Lauterbach, 2:382])

Rabbi Shimon ben Menasya’s argument resembles Jesus’ stance on qiyūm nefesh vis-à-vis the Sabbath in some remarkable ways. In Lord of Shabbat Jesus defends the disciples’ action on the grounds that David’s hunger took precedence over the sanctity of the shewbread, and therefore the disciples’ hunger should take precedence over the restrictions of the Sabbath. Like Shimon ben Menasya, Jesus’ argument takes it for granted that qiyūm nefesh takes precedence over the divine service (represented by the shewbread), and since the divine service overrides the Sabbath, qiyūm nefesh must also override the Sabbath (qiyūm nefesh > divine service > Sabbath). Likewise, Rabbi Shimon ben Menasya’s contrasting the execution of murderers with piqūaḥ nefesh resembles the contrast Jesus makes between saving versus destroying a soul on the Sabbath. This resemblance suggests that Jesus’ question—whether it is permitted to save a life or to destroy it on the Sabbath—is not merely rhetorical or hyperbolic. It is likely that his question was tapping into an ongoing debate about the prioritizing of the commandment to abstain from work on the Sabbath versus other commandments and obligations.

On the other hand, it does not follow that Jesus’ stance on qiyūm nefesh vis-à-vis the Sabbath must be understood under the rabbinic rubric of piqūaḥ nefesh. The rabbinic sages agreed that piqūaḥ nefesh applied only to cases in which the life of a person was in doubt. If a person was expected to survive beyond the Sabbath without intervention, then the restrictions of the Sabbath were not to be lifted for a sick or injured person. In the case of the man with the contractured arm, the standard of piqūaḥ nefesh would dictate that nothing be done for the sufferer until after the Sabbath was over (cf. Luke 13:14). Clearly Jesus would not have been content with the rabbinic standard of piqūaḥ nefesh. How exactly Jesus balanced the competing demands of Sabbath observance and qiyūm nefesh will be examined as our inquiry continues.

L24-30 Many scholars suppose that the author of Matthew interpolated the analogy of the sheep in the pit into Man’s Contractured Arm from another pericope, perhaps from Man with Edema, which includes a similar example of a son or an ox fallen into a cistern. However, the analogy of the sheep in the pit appears specifically tailored to address the issue of qiyūm nefesh, which Jesus raises in his counter-question to the inquiry about healing on the Sabbath. This congruence and the ease with which Matthew’s analogy reverts to Hebrew suggest that the author of Matthew found L24-30 in his parallel non-Markan source (i.e., Anth.). We have therefore included Matthew’s analogy in GR and HR.

L24 τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν ἄνθρωπος (GR). The phrase τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν (tis ex hūmōn, “Who from you?”) occurs with Lukan-Matthean agreement in Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry, L22 (Matt. 6:27 ∥ Luke 12:25). We also find τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν in Luke 11:5 (Friend in Need, L2) and Luke 14:28 (Tower Builder and King Going to War, L1), where we traced this phrase back to Anth. Since τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν formulations are characteristic of Anth., the presence of τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν in L24 is probably not due to Matthean redaction. Nevertheless, the author of Matthew is probably responsible for the presence of the verb ἔσται (estai, “will be”), which parallels his insertion of ἐστιν into a τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν phrase in Fathers Give Good Gifts, L1 (Matt. 7:9). We have therefore excluded Matthew’s ἔσται from GR.

In Fathers Give Good Gifts, L1, we encounter another τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν ἄνθρωπος (tis ex hūmōn anthrōpos, “Who among you [is] a person…?”), which is similar to the τίς ἄνθρωπος ἐξ ὑμῶν (tis anthrōpos ex hūmōn, “What person among you…?”) we encounter in Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, L12. Thus, τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν + ἄνθρωπος is probably not Matthean but a reflection of Anth.

מִי בָּכֶם אָדָם (HR). On the reconstruction of τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν (tis ex hūmōn, “Who from you?”) as מִי בָּכֶם (mi bāchem, “Who in you?”), see Tower Builder and King Going to War, Comment to L1.

On reconstructing ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos, “person,” “human”) with אָדָם (’ādām, “person,” “human”), see above, Comment to L6.

L25 ὃς ἔχων πρόβατον (GR). Our Greek reconstruction in L25 is quite close to Matthew’s wording. Because of the similar question τίς ἄνθρωπος ἐξ ὑμῶν ἔχων ἑκατὸν πρόβατα (tis anthrōpos ex hūmōn echōn hekaton probata, “What person among you having a hundred sheep…?”) in the Lost Sheep simile (L12-13; Luke 15:4), we suspect that Matthew’s future tense ἕξει (hexei, “will have”) replaced the participle ἔχων (echōn, “having”) in Anth. The future tense form would agree with Matthew’s redactional ἔσται (estai, “will be”) in L24.[96] We also suspect that Matthew’s reference to “one” sheep intentionally echoes the Lost Sheep simile (L15), which mentions “one” sheep that goes missing.[97] In the analogy of Man’s Contractured Arm the emphasis on “one” sheep is out of place, since the point of the analogy is not that the owner has only one sheep, but that no matter how many sheep he had, if any of them fell into a pit, he would take action to protect it.

On the basis of ancient Jewish parallels (cited below in Comment to L27) some scholars have suggested that Matthew’s source referred generically to a “domesticated animal” rather than to a sheep,[98] but if Anth. had referred only to a “domesticated animal,” there would have been no reason for the author of Matthew to create an allusion to the Lost Sheep simile. We have therefore retained the specific reference to a sheep in GR and HR.

שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ שֶׂה (HR). On reconstructing ὅς (hos, “who,” “which”) with -שֶׁ (she-, “who,” “that”), see Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl, Comment to L5.

On reconstructing ἔχειν (echein, “to have”) with -יֵשׁ לְ (yēsh le–, “there is to”), see Tower Builder and King Going to War, Comment to L4.

On reconstructing πρόβατον (probaton, “sheep”) with שֶׂה (seh, “sheep”), see Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, Comment to L32.[99]

L26 καὶ ἐὰν ἐμπέσῃ (GR). We have accepted nearly all of Matthew’s wording in L26 for GR, since it easily reverts to Hebrew and there are parallels to Matthew’s exact phrasing in ancient Hebrew sources that deal with nearly identical scenarios (see below). The only difference between GR and Matthew in L26 is our omission of the demonstrative pronoun τοῦτο (touto, “this”). This demonstrative pronoun both clears up a slight ambiguity in the sentence—τοῦτο (“this [sheep]”]) makes explicit the subject of ἐμπέσῃ (“he/she/it might fall”)—and it places emphasis on the singularity of the “one” sheep, an emphasis which in L25 we attributed to Matthean redaction. Since τοῦτο can be explained as a grammatical improvement and since it is also consistent with the author of Matthew’s redactional interests, τοῦτο is best excluded from GR.

וְאִם יִפֹּל (HR). On reconstructing ἐάν (ean, “if”) with אִם (’im, “if”), see Sending the Twelve: Conduct in Town, Comment to L88.

In LXX the verb ἐμπίπτειν (empiptein, “to fall in”) nearly always occurs as the translation of נָפַל (nāfal, “fall”).[100] Although the LXX translators usually rendered נָפַל as πίπτειν,[101] ἐμπίπτειν is by no means so unusual a translation that we need have any doubt as to HR.

L27 ἐν τῷ σαββάτῳ εἰς βόθυνον (GR). As in L10, we suspect that the author of Matthew replaced Anth.’s ἐν τῷ σαββάτῳ (en tō sabbatō, “in the Sabbath”) with the plural τοῖς σάββασιν (tois sabbasin, “to the Sabbaths”). There the author of Matthew was influenced by the parallel in Mark. Here, where Matthew’s only source is Anth., the lingering influence of Mark’s wording in L10 continues to be felt. Aside from this minor adjustment, we have accepted Matthew’s wording in L27 for GR.

בַּשַּׁבָּת אֶל פַּחַת (HR). On reconstructing σάββατον (sabbaton, “Sabbath”) with שַׁבָּת (shabāt, “Sabbath”), see above, Comment to L2.

In LXX the noun βόθυνος (bothūnos, “hole,” “pit”) usually occurs as the translation of פַּחַת (paḥat, “pit”),[102] and we also find that the LXX translators nearly always rendered פַּחַת as βόθυνος.[103] Ancient Jewish sources frequently refer to the scenario of an animal fallen into a hole on the Sabbath. In rabbinic sources we typically find references to a בּוֹר (bōr, “cistern,” “pit”), but in a Qumran text we find בּוֹר (“cistern”) paired with פַּחַת (“pit”):

אל יילד איש בהמה ביום השבת ואם תפול אל בור ואל פחת אל יקימה בשבת

A man must not help a domesticated animal give birth on the Sabbath day. And if it falls into a cistern [בּוֹר] or into a pit [פַּחַת], he may not sustain it[s life][104] on the Sabbath. (CD XI, 13-14; corrected on the basis of 4Q271 5 I, 8-11)

בהמה שנפלה לתוך הבור עושין לה פרנסה במקומה בשביל שלא תמות

A domesticated animal that fell [on the Sabbath—JNT and DNB] into a cistern [הַבּוֹר]: they sustain it where it is, so that it will not die. (t. Shab. 14:3; Vienna MS)

בְּכוֹר שֶׁנָּפַל לַבּוֹר ר′ יְהוּדָה אוֹ′ יֵרֵד מוּמְחֶה וְיִרְאֶה אִם יֶשׁ בּוֹ מוּם יַעֲלֶה וְיִשְׁחוֹט וְאִם לָאו לֹא יִשְׁחוֹט