Matt. 24:15-16, 19-22; Mark 13:14, 17-20; Luke 21:20-24

(Huck 216; Aland 290; Crook 328)[1]

Updated: 5 December 2024

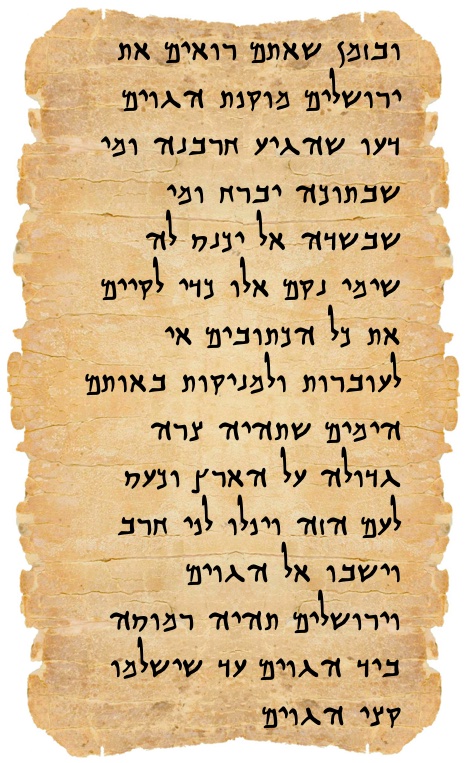

וּבִזְמָן שֶׁאַתֶּם רוֹאִים אֶת יְרוּשָׁלַיִם מוּקֶּפֶת הַגּוֹיִם דְּעוּ שֶׁהִגִּיעַ חָרְבָּנָהּ וּמִי שֶׁבְּתוֹכָהּ יִבְרַח וּמִי שֶׁבַּשָּׂדֶה אַל יִכָּנֵס לָהּ שֶׁיְּמֵי נָקָם אֵלּוּ כְּדֵי לְקַיֵּים אֶת כָּל הַכְּתוּבִים אִי לָעוּבָּרוֹת וְלַמֵּנִיקוֹת בְּאוֹתָם הַיָּמִים שֶׁתִּהְיֶה צָרָה גְדוֹלָה עַל הָאָרֶץ וְכַעַס לָעָם הַזֶּה וְיִפְּלוּ לְפִי חֶרֶב וְיִשָּׁבוּ אֶל הַגּוֹיִם וִירוּשָׁלַיִם תִּהְיֶה רְמוּסָה בְּיַד הַגּוֹיִם עַד שֶׁיִּשְׁלְמוּ קִצֵּי הַגּוֹיִם

“But when you see Yerushalayim besieged by Gentiles, rest assured that the hour of her destruction has come at last. Whoever is inside Yerushalayim at that time should flee. And no one outside the walls when the siege closes in should enter the city. For these are days of vengeance, in order to fulfill all the Scripture passages concerning it.

“Alas for the pregnant women and the nursing mothers when all this takes place! For there will be great distress in the land of Israel as God’s wrath is poured out on our people. Some will be killed, and some will go into captivity to foreign places. And the Gentiles will trample Yerushalayim until their times are complete.[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Yerushalayim Besieged click on the link below:

| “Destruction and Redemption” complex |

| Temple’s Destruction Foretold ・ Tumultuous Times ・ Yerushalayim Besieged ・ Son of Man’s Coming ・ Fig Tree parable |

Story Placement

In the Gospel of Luke, between Tumultuous Times (Luke 21:10-11) and Yerushalayim Besieged (Luke 21:20-24), there appears a series of sayings dealing with the hostility Jesus expected his followers would encounter as they bore witness to him (Luke 21:12-19). There are three reasons for supposing that the sayings in Luke 21:12-19 are extraneous to Jesus’ original prophecy of destruction and redemption. First, in Luke 21:12-19 the audience is clearly limited to the followers of Jesus, whereas the rest of the prophecy of destruction and redemption is addressed to and concerns the general public of Jerusalem (see Luke 21:5-7). Second, Luke 21:12-19 is out of chronological sequence, for according to Luke 21:12 the hostilities Jesus’ followers will endure will happen before the things described in Tumultuous Times. Thus, the flashback in Luke 21:12-19 interrupts the progression of events, which is not resumed until Yerushalayim Besieged (Luke 21:20-24).[3] Third, each of the sayings in Luke 21:12-19 either has a doublet elsewhere in Luke or has a parallel in parts of Matthew outside Matthew’s eschatological discourse (Matt. 24).[4] The parallels to Luke 21:12-19 in other parts of Luke and/or Matthew strongly suggest that these sayings were originally unrelated to Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption. The combined evidence leads us to the conclusion that the sayings in Luke 21:12-19 were secondarily inserted between Tumultuous Times and Yerushalayim Besieged by a redactor of the synoptic materials. We have accordingly omitted Luke 21:12-19 (and the Markan and Matthean parallels) from our reconstruction of the “Destruction and Redemption” complex.

In the Gospels of Mark and Matthew the placement of Yerushalayim Besieged is the same as in Luke, but since their versions of this pericope have been so heavily redacted (mostly by the author of Mark), Yerushalayim Besieged is no longer an apt title for the Markan and Matthean parallels to Luke 21:20-24. A better name for the pericope consisting of Mark 13:14-20 ∥ Matt. 24:15-22 might be Abomination of Desolation, since it is the appearance of this mysterious object (or person?)—not the siege of Jerusalem as in Luke—that sets in motion the events described in the Markan and Matthean versions of this pericope.

For an overview of the “Destruction and Redemption” complex, click here.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

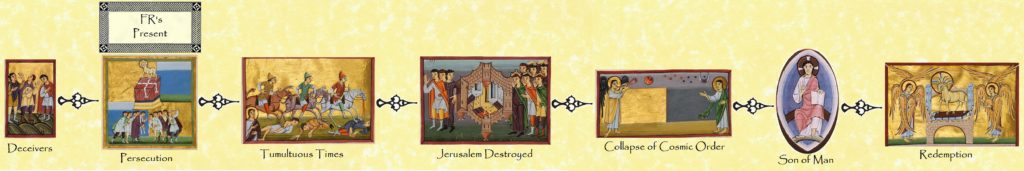

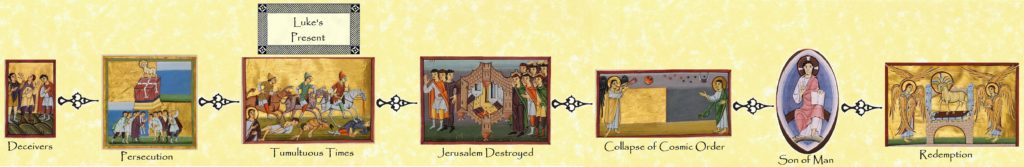

Typically, our Story Placement discussions focus on where a given pericope is placed in relation to other pericopae in a particular Gospel or in the pre-synoptic sources. Here, however, it will also be useful to discuss a different kind of story placement, namely where each of the Gospel writers and the authors of the pre-synoptic sources saw themselves chronologically placed in relation to the events described in Yerushalayim Besieged (or Abomination of Desolation in Mark and Matthew). In other words, it is necessary to assess whether a given writer placed the events described in Yerushalayim Besieged/Abomination of Desolation in the past, the present or the future.

If, as we suppose, the core prophecy of destruction and redemption, which was still preserved in Anth., originated with Jesus,[5] then all the events described in the “Destruction and Redemption” complex were envisioned as taking place in the future. The First Reconstructor’s “updating” of Jesus’ prophecy by inserting sayings about the difficulties Jesus’ followers would face gives us an important clue regarding where the First Reconstructor saw himself within the timeline of Jesus’ prophecy. The First Reconstructor’s insertion of Like Lightning (Luke 21:8-9) into the prophecy suggests that he was living at a time when false prophets and messianic pretenders had gathered followings in Judea. Such events are known to have occurred by the mid-40s C.E.[6] The First Reconstructor’s insertion of the sayings in Luke 21:12-19 that describe hostility toward Jesus’ followers interrupts the chronological progression of the prophecy. It is a flashback to events that are to take place before the appearance of signs that the Temple’s destruction is at hand. The urgency of these sayings and the fact that the First Reconstructor took the trouble to insert them into Jesus’ prophecy suggest that the hostilities were recent and perhaps ongoing events for the First Reconstructor and his readers. Another change the First Reconstructor made to the prophecy is the addition of a directive to “those in Judea” to flee to the mountains (Luke 21:21) (see below, Comment to L11-12). This addition suggests that the First Reconstructor sought to make Jesus’ warnings to the people of Jerusalem relevant to a wider audience consisting of believing congregations scattered throughout Judea. Paul’s epistle to the Thessalonians attests to the presence of persecuted congregations in Judea ca. 50 C.E. (1 Thess. 2:14). It therefore seems likely that the First Reconstructor updated Jesus’ prophecy to reflect the conditions his community was experiencing in the early to mid-50s C.E. Thus, for the First Reconstructor the destruction of the Temple still loomed in the future.

Our identification of the First Reconstructor’s present in the middle of the first century C.E. explains why FR’s version of Yerushalayim Besieged does not contain specific details about Jerusalem’s destruction as it actually happened in 70 C.E.[7] The description of Jerusalem’s fall in Luke 21:20-24 is so generic as to describe almost any Roman siege.[8] It does not contain an account of the terrible famine that killed so many of Jerusalem’s inhabitants. Neither does it describe how the Temple was burned. The prophecy does not even challenge the popular opinion that the Temple was the most secure part of the city. There were those in Jesus’ time who believed that even if Jerusalem fell, the Temple would remain inviolate.[9] But in 70 C.E. the Temple fell to the Romans first. And while the lower city was soon subdued, the upper city continued to resist for another month after the Temple was destroyed.[10] The reason such details are absent from FR’s prophecy is that the destruction had not yet taken place. The prophecy predicted what anyone might anticipate;[11] the unforeseeable particulars of 70 C.E. and surprises no one expected are understandably absent.

The author of Luke made changes to FR’s prophecy that indicate where he thought he belonged in the prophecy’s chronology. As we discussed in the commentary to Tumultuous Times, the author of Luke rearranged the order of catastrophes in order to show that some of the signs that the Temple’s destruction was approaching had already begun to manifest themselves (namely earthquakes and famine). Thus, for the author of Luke the Temple’s destruction was still in the future, but he believed that its downfall was imminent. Since the events recorded in Acts take us up to the years 62-64 C.E., and since the author of Luke probably completed his two-volume work shortly after the events he described, we may suppose that the author of Luke composed his Gospel before the outbreak of the Jewish revolt in 66 C.E.[12] A pre-70 C.E. date for Luke’s Gospel explains why the author of Luke was unable to add to the prophecy any historical details about the destruction of the Temple and the fall of Jerusalem.[13] When the author of Luke composed his Gospel, the destruction of the Temple was still in the future.

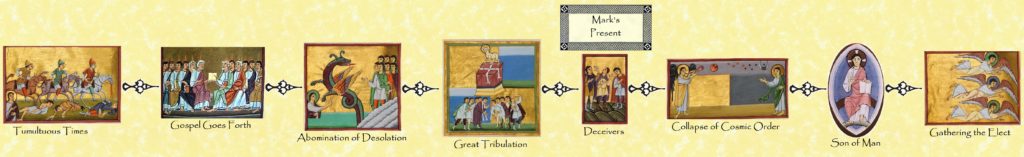

Just as the redactional activity of the First Reconstructor and the author of Luke offers clues to where each writer saw himself in the chronology of Jesus’ prophecy, so the author of Mark’s editorial interventions likely indicate where he saw himself in the prophecy’s chronological scheme. While Markan redaction is pervasive throughout the prophecy, the character of Mark’s redaction drastically changes in Mark 13:14-20. At this point the author of Mark’s redactional activity becomes so intense that, as we noted above, Yerushalayim Besieged is no longer a fitting title for his version of this pericope. The author of Mark replaced Luke’s wording with apocalyptic imagery (i.e., “the abomination of desolation”) and sectarian language (i.e., “the elect”). The author of Mark’s reworking of Yerushalayim Besieged also hints that his revisions offer a retrospective view of what happened in 70 C.E. The author of Mark was careful to have Jesus speak in the future tense, but when the author of Mark inserted a comment of his own (Mark 13:20), he described the time of intense suffering that happened in the wake of the appearance of the abomination of desolation in the past tense: the Lord cut those days off for the sake of the elect (see below, Comment to L55). The author of Mark’s insertion of a second version of Like Lightning at Mark 13:21-23 probably indicates that these verses describe current events for the author of Mark and his readers. These verses are given special emphasis, with Jesus stating that, having warned the disciples in advance about these things, they must be on their guard (Mark 13:23). Likewise, Mark 13:24 suggests that Mark’s readers were living in the time between the great tribulation and the beginning of the end. At any time the cosmic order would be upset and the Son of Man would send his angels to gather the elect. The author of Mark understood himself to be living in the eye of the storm. The intense suffering occasioned by the destruction of Jerusalem had passed; what remained of the universe might crumble at any moment.[14] It thus appears that Mark’s Gospel was composed in the wake of the Temple’s destruction, at a time when the recollection of those traumatic events still provoked a visceral response from his readers.

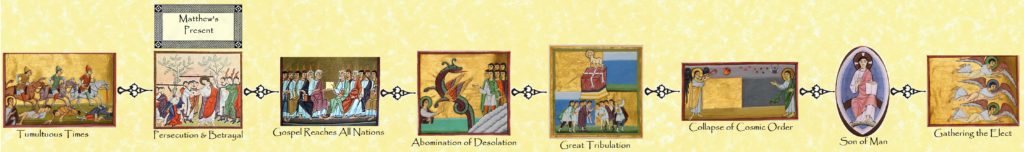

Matthew’s chronological standpoint is surprising. The author of Matthew’s most extensive redaction of Mark’s material occurs in the section describing the hostilities Jesus’ followers will encounter before the abomination of desolation appears (Matt. 24:9-14). While the author of Matthew acknowledges that Jesus’ followers will encounter hostilities from the outside, he was more concerned about betrayals, false teaching, lawlessness and defections within his community. Matthew’s description of internicene strife is similar to the eschatological forecast in the final chapter of the Didache (Did. 16:1-8), according to which the church will be riddled with lawlessness and betrayal. According to Matt. 24:14, the gospel must be preached to all nations, and then the end will come.[15] Thus, the author of Matthew saw himself living at a time before the end when the gospel was being proclaimed but the church was beset with inner conflicts.[16]

According to the author of Matthew, once the gospel has been proclaimed to all nations, the end will come about as a response to the appearance of the abomination of desolation. The abomination of desolation will spark a chain reaction of tribulation for the elect, the upset of the cosmic order, and the coming of the Son of Man to gather the elect and punish the wicked.[17] From this we learn that the author of Matthew envisioned the abomination of desolation as a future event.[18] But this does not mean that Matthew’s version of Jesus’ prophecy is pre-70 C.E. On the contrary, the author of Matthew reworked Mark’s post-70 C.E. version of the prophecy to suit his own purposes. Rather than being ignorant of the events of 70 C.E., it appears that for the Matthean community the events of 70 C.E. had little or no significance. Perhaps those events had taken place so long ago that Matthew’s readers had learned to adjust to the new circumstances and needed to recalibrate their eschatological timetable. Or perhaps the Matthean community was so utterly estranged from the Jewish people that it regarded the destruction of the Temple and the fall of Jerusalem as irrelevant. Or perhaps both factors were at play. In any case, Matthew’s eschatological timeline is remarkable in that the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E. is regarded as an insignificant event of the past (it does not even merit a reference in Matthew’s version of Jesus’ prophecy), but the abomination of desolation is nevertheless regarded as a future event.[19] In any case, our conclusions regarding the author of Matthew’s view of his chronological placement of Jesus’ prophecy are consistent with our dating of Matthew’s Gospel to the late first or early second century C.E.[20]

Recognizing that different chronological schemes are represented in the various versions of Jesus’ prophecy is crucial for understanding each version of the prophecy on its own terms.

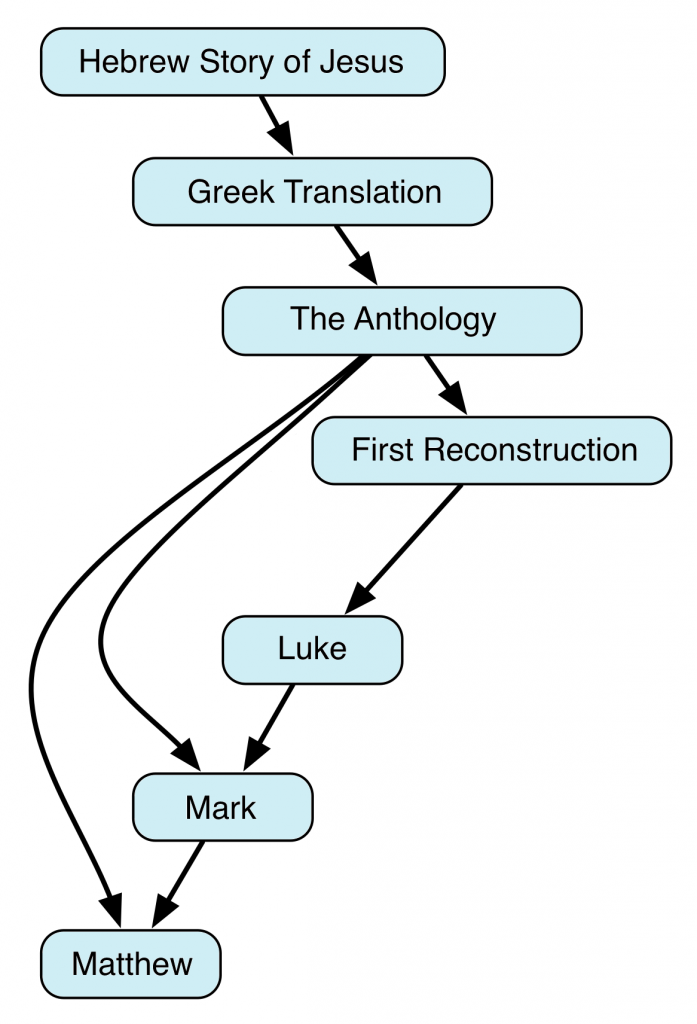

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

There are two prevailing opinions with respect to the transmission of Yerushalayim Besieged. Either Luke’s version is a thoroughgoing revision of Mark’s,[21] or in addition to Mark the author of Luke relied on some other source for his version of Yerushalayim Besieged.[22] These opinions reflect 1) the fact that there is a wide divergence between the Lukan and Markan (and Matthean) versions of Yerushalayim Besieged and 2) the assumption of Markan Priority. Lindsey’s hypothesis combines the insights of these two prevailing opinions but provides a new twist: Luke’s version of Yerushalayim Besieged is based on a non-Markan source, and radical revision does account for the divergence between the Lukan and Markan versions, but it was not the author of Luke who reworked Mark, it was the author of Mark who reworked Luke.

The reason the author of Mark so radically reworked Luke’s Yerushalayim Besieged, transforming it into Abomination of Desolation, is that he viewed Yerushalayim Besieged in light of his post-70 C.E. experience through an apocalyptic lens. The author of Matthew similarly adapted Mark’s version of Abomination of Desolation to conform to his worldview and experience.

Crucial Issues

- What (or who) was “the abomination of desolation”?

- Why does Matthew’s version mention fleeing on the Sabbath?

- Does Yerushalayim Besieged contain an authentic prophecy of Jesus, or were the events of 70 C.E. projected back onto Jesus by the authors of the Gospels and their sources?

Comment

L1 καὶ ὅταν ἴδητε (GR). All three Gospels are agreed on the words ὅταν (hotan, “when”) and ἴδητε (idēte, “you might see”) in L1. Where they differ is with regard to the conjunction between these two words. Whereas Luke and Mark have δέ (de, “but”), Matthew has οὖν (oun, “therefore”). Matthew’s conjunction looks like a Greek stylistic improvement that the author of Matthew introduced in order to make a tighter connection with the preceding verse. In Matt. 24:14 the author of Matthew has Jesus declare that once the Gospel has reached all the Gentiles the end will come. The οὖν in Matt. 24:15 implies that the appearance of the abomination of desolation is the beginning of the end,[23] which, for the author of Matthew and his readers, still lay in the future.

We think it is likely that δέ, too, is a Greek stylistic improvement introduced by the First Reconstructor into Yerushalayim Besieged. If so, the δέ was passed along from FR to Luke and from Luke to Mark. If δέ in L1 stems from FR, presumably Anth. had the conjunction καί (kai, “and”) before ὅταν, which is the reading we have adopted for GR.

וּבִזְמָן שֶׁאַתֶּם רוֹאִים (HR). In LXX ὅταν + subjunctive often occurs as the translation of -בְּ + infinitive construct.[24] In Mishnaic Hebrew, however, the use of -בְּ + infinitive construct was discontinued, being replaced by -כְּשֶׁ + verb.[25] However, the phrase -בִּזְמָן שֶׁ (bizmān she-, “in a/the time that”) was an even more common way of expressing “when” in Mishnaic Hebrew than -כְּשֶׁ (keshe-, “as that,” “when that”), with numerous examples of -בִּזְמָן שֶׁ appearing in the Mishnah in answer to the question אֵמָתַי (’ēmātai, “When?”).[26] Moreover, we find a precise grammatical parallel to our reconstruction (-בִּזְמָן שֶׁ + you see ___→imperative) in the following example:

בזמן שאתה רואה רשעים שרבו כמו עשב…צפה לימות המשיח

When you see wicked persons, that they have increased like grass…look for the days of the anointed one [i.e., the Messiah—DNB and JNT]. (Midrash Tehillim 92:10 [ed. Buber, 309])

On reconstructing ἰδεῖν (idein, “to see”) with רָאָה (rā’āh, “see”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L10.

Hebrew has no exact equivalent to the subjunctive mood. The present context calls for either a future verb or a participle. In the rabbinic parallel quoted above a participle is used with reference to the future. Our reconstruction follows suit.

L2-4 κυκλουμένην ὑπὸ στρατοπέδων Ἰερουσαλήμ (Luke 21:20). As Dodd observed, “It will hardly be argued that the mere expression κυκλουμένην ὑπὸ στρατοπέδων [‘surrounded by camps’—DNB and JNT], describes Titus’s siege so precisely that it must necessarily be a ‘vaticinium ex eventu’ [i.e., a prophecy after the event—DNB and JNT]. If you want to say in Greek ‘Jerusalem will be besieged’, the choice of available expressions is strictly limited, and κυκλοῦσθαι ὑπο στρατοπέδων is about as colorless as any.”[27] Predicting a siege of Jerusalem should not have been difficult for Jesus, who was sensitive to (and critical of) the direction the political winds were blowing. There is no a priori reason why Jesus could not have made such a prediction, and the hesitation of some scholars to trace back to Jesus the prediction of Jerusalem’s siege in Luke 21:20 is mainly due to their assumption that Luke is dependent upon Mark. The assumption of Markan Priority leads many scholars to the further assumption that the author of Luke must have rewritten Jesus’ prophecy in light of the events of 70 C.E. We do not share these assumptions. Rather, it appears to us that the author of Luke transmitted an authentic prediction of Jesus that Jerusalem would fall in a Roman siege, and it was the author of Mark who dropped the description of the siege in order to replace it with the apocalyptic image of the abomination of desolation. The author of Matthew subsequently adopted Mark’s reworked version of Jesus’ prophecy.

L2 Ἰερουσαλὴμ κυκλουμένην (GR). Luke’s word order in L2-4 is un-Hebraic. We suspect this un-Hebraic word order is due to the First Reconstructor’s editorial activity. For GR we have relocated the noun Ἰερουσαλήμ (Ierousalēm, “Jerusalem”), which in Luke appears in L4, to a more Hebraic position in L2.

אֶת יְרוּשָׁלַיִם מוּקֶּפֶת (HR). On reconstructing Ἰερουσαλήμ (Ierousalēm, “Jerusalem”) as יְרוּשָׁלַיִם (yerūshālayim, “Jerusalem”), see Yeshua’s Testing, Comment to L65. Note that Ἰερουσαλήμ is the Hebraic form of the name Jerusalem. Greek authors often preferred the Hellenized form Ἱεροσόλυμα (Hierosolūma). While the use of the Hebraic form Ἰερουσαλήμ in no way proves that Luke 21:20 is ultimately derived from a Hebrew source, it does at least allow for this intriguing possibility.[28]

In LXX the verb κυκλοῦν (kūkloun, “to surround”) usually occurs as the translation of verbs formed from the ס-ב-ב root.[29] Likewise, the LXX translators more often rendered ס-ב-ב verbs as κυκλοῦν than as any other Greek equivalent.[30] Nevertheless, in the context of a siege, verbs from the root נ-ק-פ are more appropriate, as the following examples demonstrate:

והוא לכול מבצר ישחק ויצבור עפר וילכדהו פשרו על מושלי הכתיאים אשר יבזו על מבצרי העמים ובלעג ישח{ו}קו עליהם ובעם רב יקיפום לתפושם

And he laughs at every fortress, and he heaps up dust and captures it [Hab. 1:10]. Its interpretation concerns the rulers of the Kittim [i.e., the Romans—DNB and JNT],[31] who disdain the fortresses of the people and with scorn laugh at them and with a great people they besiege them [יקיפום] to capture them. (1QpHab IV, 3-7)

וְעַל אֵילּוּ מַתְרִיעִים בַּשַּׁבָּת עַל עִיר שֶׁהִיקִּיפוּהָא גוֹיִם

And on account of these they sound the warning on the Sabbath: on account of a city that Gentiles have besieged [שֶׁהִיקִּיפוּהָא]…. (m. Taan. 3:7)

עיר שהקיפוה גוים …וכן היחיד שהיה נרדף מפני גוים…הרי אילו מחללין את השבת ומצילין את עצמן

A city that the Gentiles besieged [שהקיפוה]…and also an individual who was pursued by Gentiles…. Behold! These profane the Sabbath and save themselves. (t. Eruv. 3:8; Vienna MS)

וכשבא אספסיאנוס והקיף את ירושלים….

When Vespasian came and besieged [והקיף] Jerusalem…. (Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version B, §7 [ed. Schechter, 20])

Whereas in the examples above we find נ-ק-פ in the active hif‘il stem, for HR we have adopted a passive hof‘al participle. The feminine participle מוּקֶּפֶת (mūqefet, “besieged,” “surrounded”) is well attested in rabbinic sources. For instance, in the Mishnah we read of הַגַּנָּה…מוּקֶּפֶת גָּדֵר (haganāh…mūqefet gādēr, “a garden…surrounded by a fence”; m. Eruv. 2:5; cf. m. Edu. 2:4) and חָצֵר שֶׁהִיא מוּקֶּפֶּת אַכְסַדְרָא (ḥātzēr shehi’ mūqepet ’achsadrā’, “a courtyard that is surrounded by a peristyle”; m. Suk. 1:10; m. Ohol. 14:4). Likewise, in the Tosefta we encounter the question ′היכן מצינו לשושן הבירה שמוקפת חומ (“Where do we find concerning Shushan, the capital, that it was surrounded by a wall?”; t. Meg. 1:1; Vienna MS). In Yerushalayim Besieged, instead of being surrounded for its protection, as in the examples just cited, Jerusalem is surrounded by Roman encampments.

In LXX there are a few examples where κυκλοῦν (“to surround”) occurs as the translation of הִקִּיף (hiqif, “surround,” “besiege”):

וְהִקַּפְתֶּם עַל הַמֶּלֶךְ סָבִיב אִישׁ וְכֵלָיו בְּיָדוֹ

…and you must encircle the king all around, each man with his weapons in his hand…. (2 Kgs. 11:8)

καὶ κυκλώσατε ἐπὶ τὸν βασιλέα κύκλῳ, ἀνὴρ καὶ τὸ σκεῦος αὐτοῦ ἐν χειρὶ αὐτοῦ

…and you must encircle the king all around, each man with his weapon in his hand…. (4 Kgdms. 11:8)

וְהִקִּיפוּ הַלְוִיִּם אֶת הַמֶּלֶךְ סָבִיב אִישׁ וְכֵלָיו בְּיָדוֹ

And the Levites will encircle the king all around, each man with his weapons in his hand. (2 Chr. 23:7)

καὶ κυκλώσουσιν οἱ Λευῖται τὸν βασιλέα κύκλῳ, ἀνδρὸς σκεῦος ἐν χειρὶ αὐτοῦ

And the Levites will encircle the king all around, each man with a weapon in his hand. (2 Chr. 23:7)

בָּנָה עָלַי וַיַּקַּף רֹאשׁ

He built against me and encircled [my] head…. (Lam. 3:5)

ἀνῳκοδόμησεν κατ᾿ ἐμοῦ καὶ ἐκύκλωσεν κεφαλήν μου

He built up against me and encircled my head…. (Lam. 3:5)

There is also an example where περικυκλοῦν (perikūkloun, “to encompass,” “to surround”), a compound form of κυκλοῦν, occurs as the translation of הִקִּיף:

וַיִּשְׁלַח שָׁמָּה סוּסִים וְרֶכֶב וְחַיִל כָּבֵד וַיָּבֹאוּ לַיְלָה וַיַּקִּפוּ עַל הָעִיר

And he sent there horses and chariots and a great army, and they came by night and lay siege against the city. (2 Kgs. 6:14)

καὶ ἀπέστειλεν ἐκεῖ ἵππον καὶ ἅρμα καὶ δύναμιν βαρεῖαν, καὶ ἦλθον νυκτὸς καὶ περιεκύκλωσαν τὴν πόλιν

And he sent there horses and chariots and a mighty force, and they came by night and surrounded the city. (4 Kgdms. 6:14)

L3 ὑπὸ ἐθνῶν (GR). In LXX στρατόπεδον (stratopedon, “camp,” “encamped army”) is quite rare and only occurs twice where there is a Hebrew equivalent.[32] These two instances are both in Jeremiah, where στρατόπεδον once occurs as the translation of חַיִל (ḥayil, “army”; Jer. 41[34]:1) and once as the translation of אִישׁ (’ish, “man”; Jer. 48[41]:12). Delitzsch, quite understandably, rendered στρατόπεδον in Luke 21:20 with מַחֲנֶה (maḥaneh, “camp”), but we never read in rabbinic sources of a city surrounded by camps (neither עִיר מוּקֶּפֶת מַחֲנוֹת nor עִיר שֶׁהִקִּיפוּהָ מַחֲנוֹת). On the other hand, in the examples collected in Comment to L2 we do read of cities surrounded by Gentiles. This observation caused us to notice that in the rest of Yerushalayim Besieged the agents of Jerusalem’s destruction are identified as Gentiles (L44, L46, L49). Perhaps, therefore, the antagonists in L3 were originally identified as Gentiles, too. If Anth. had read ὑπὸ ἐθνῶν (hūpo ethnōn, “by Gentiles”) in L3, the author of Luke or, more likely, the First Reconstructor may have considered “surrounded by Gentiles” too bland a description and replaced it with the more vivid ὑπὸ στρατοπέδων (hūpo stratopedōn, “by encampments”).

Another reason for supposing that Jesus’ prophecy originally referred to Jerusalem being surrounded by Gentiles is that such a description would be reminiscent of a prophecy in Zechariah:

וְאָסַפְתִּי אֶת כָּל הַגּוֹיִם אֶל יְרוּשָׁלִַם לַמִּלְחָמָה וְנִלְכְּדָה הָעִיר וְנָשַׁסּוּ הַבָּתִּים וְהַנָּשִׁים תשגלנה [תִּשָּׁכַבְנָה] וְיָצָא חֲצִי הָעִיר בַּגּוֹלָה וְיֶתֶר הָעָם לֹא יִכָּרֵת מִן הָעִיר

And I will gather all the Gentiles [LXX: τὰ ἔθνη] to Jerusalem for war, and the city will be captured, and the houses will be plundered, and the women raped, and half the city will go out in exile, but the rest of the people will not be cut off from the city. (Zech. 14:2)

That Zech. 14:2 influenced Jesus’ prophecy is likely given their similar structures, which become apparent when they are presented for side-by-side comparison:

| Zech. 14:2 | Luke 21:20-24 |

| And I will gather all the Gentiles to Jerusalem for war, and the city will be captured, | When you see Jerusalem surrounded by camps, know that its desolation is near. |

| Then let the ones in Judea flee to the hills, and the ones inside it [i.e., the city] depart, and the ones in the country not enter it. For these are days of vengeance, to fulfill all the things written. | |

| and the houses will be plundered, and the women raped, | Woe to those who are pregnant and to those who are nursing infants in those days! For there will be great distress in the land and wrath toward this people. |

| and half the city will go out in exile, but the rest of the people will not be cut off from the city. | And they will fall by the mouth of the sword and will be made captive to all the Gentiles, and Jerusalem will be trampled by the Gentiles until the times of the Gentiles are fulfilled. |

While the similarity of Luke 21:20-24 to Zech. 14:2 is not sufficient on its own to prove that Jesus’ prophecy originally referred to Gentiles instead of camps, it does provide further support for this suggestion, which we have made on linguistic and contextual grounds.

הַגּוֹיִם (HR). On reconstructing ἔθνος (ethnos, “people group,” “Gentile”) with גּוֹי (gōy, “people group,” “Gentile”), see Sending the Twelve: Conduct on the Road, Comment to L52.

In HR we have nothing equivalent to the Greek preposition ὑπό (hūpo, “by”), for as we saw in the examples of מוּקֶּפֶת (“besieged,” “surrounded”) cited in Comment to L2, מוּקֶּפֶת + noun means “surrounded/besieged by X.” Thus, מוּקֶּפֶת גּוֹיִם means “surrounded/besieged by Gentiles.”

L5 γνῶτε ὅτι ἤγγικεν (GR). While we cannot be certain, we suspect that τότε (tote, “then”) in L5 is an editorial addition from the First Reconstructor’s pen. We have accordingly omitted τότε from GR.

דְּעוּ שֶׁהִגִּיעַ (HR). On reconstructing γινώσκειν (ginōskein, “to know”) with יָדַע (yāda‘, “know”), see Mysteries of the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L6.

In LXX the verb ἐγγίζειν (engizein, “to approach”) occurs far more often as the translation of קָרַב (qārav, “approach”) than of הִגִּיעַ (higia‘, “arrive”),[33] but there are reasons for supposing that הִגִּיעַ is a better option for HR. First, we have found elsewhere in LOY that the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua likely rendered ἐγγίζειν as הִגִּיעַ.[34] Second, in Tumultuous Times Jesus had already given signs that the Temple’s destruction was approaching. The context in Yerushalayim Besieged calls for an upping of the stakes from “it’s close” to “it’s here.” Third, having been encompassed by its enemies, Jerusalem’s destroyer really had arrived. The destruction may not have been accomplished, but the fate of the city had been sealed. Finally, reconstructing with הִגִּיעַ lends the prophecy sufficient urgency to justify the command to abandon the city that Jesus is about to issue.[35]

L6 ἡ ἐρήμωσις αὐτῆς (GR). From the perspective of Lindsey’s hypothesis it is clear that the words “her [i.e., Jerusalem’s] desolation” in Luke 21:20 afforded the author of Mark an opportunity to reinterpret Jesus’ prophecy in light of the “abomination of desolation” mentioned in the book of Daniel (Dan. 9:27; 12:11).[36] This change is only one example of the author of Mark’s Danielic revision of Jesus’ prophecy. The author of Mark introduced additional allusions to Daniel in Mark 13:4 (cf. Dan. 12:6-7)[37] and Mark 13:19 (cf. Dan. 12:1) (see below, Comment to L38). The impetus for these Danielic revisions in Mark was surely the reference to the Son of Man’s coming in a cloud in Luke 21:27 (cf. Dan. 7:13). This allusion to Daniel’s apocalyptic vision inspired the author of Mark to give Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption an apocalyptic twist.[38] It is unlikely, however, that the Markan revisions were simply inspired by Luke’s wording. His revisions of the prophecy were probably also informed by his community’s lived experience of the destruction of the Temple and their recollections of the fall of Jerusalem. Otherwise, the Danielic revision of Jesus’ prophecy would not ring true to his audience. Only if Mark’s readers were able to say, “Yes! It was like that” would the Danielic revisions have their desired effect, which was surely to instill confidence in the readers of Mark that Jesus, the Son of Man, was swiftly coming to rescue them.

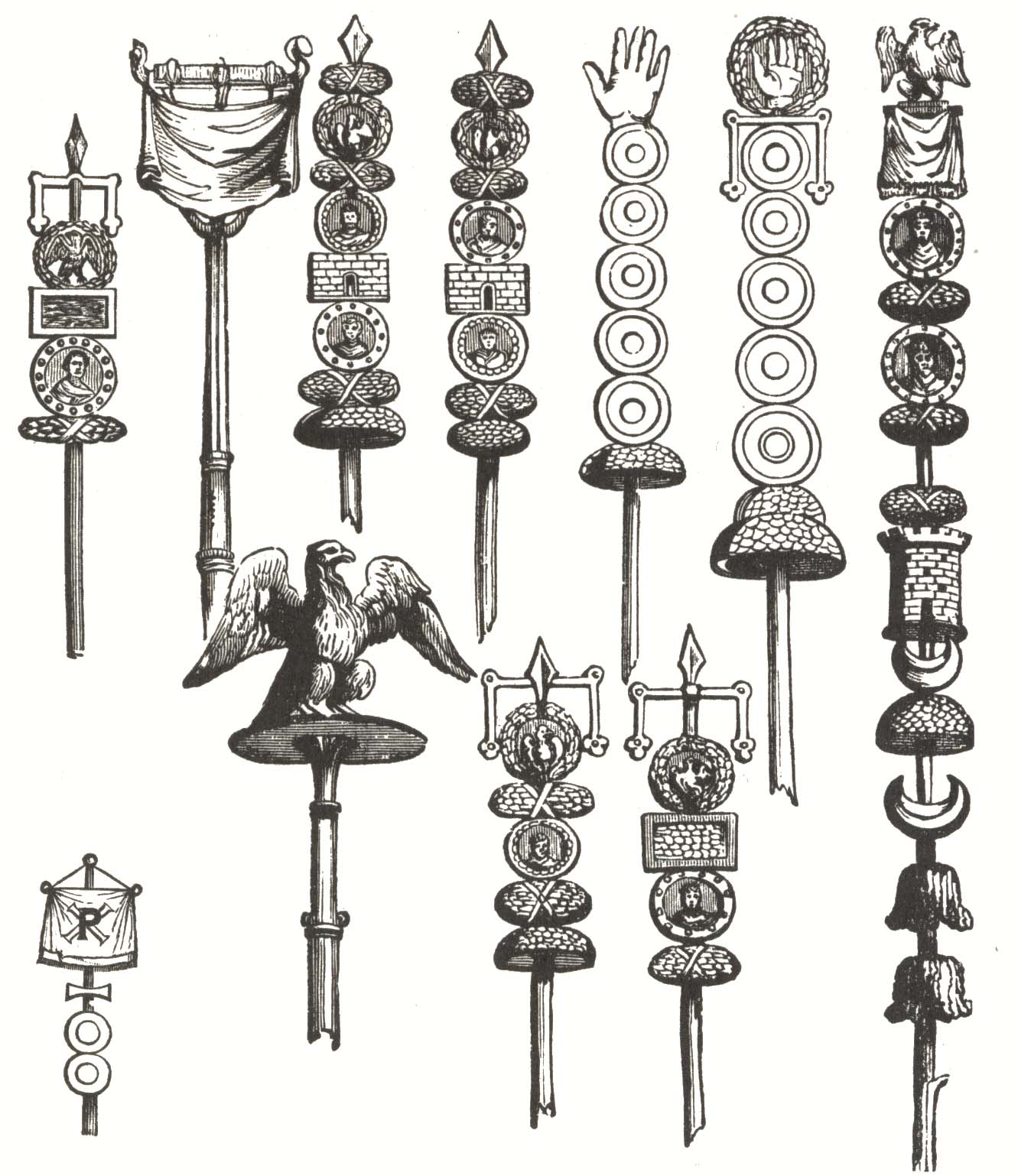

To what, then, did “the abomination of desolation” in Mark 13:14 refer? In Daniel the “abomination of desolation” (שִׁקּוּץ שֹׁמֵם [shiqūtz shomēm]; Dan. 12:11; cf. variants in Dan. 9:27; 11:31) is a cryptogram for Olympian Zeus (= Baal Shamayim),[39] in whose name Antiochus IV Epiphanes rededicated Jerusalem’s Temple (2 Macc. 6:2) and whose altar was erected in the place of the altar of burnt offerings in the Temple courts (1 Macc. 1:54). Evidently, the author of Mark believed that an analogous profanation of the Temple occurred during the Roman destruction of Jerusalem. We know of two events that occurred in 70 C.E. which might be construed as analogous to the profanation of the Temple in the days of Antiochus: 1) Titus’ entry into the Holy of Holies and 2) the sacrifice of the victorious Roman soldiers to their military standards on the Temple Mount.

Titus’ entry into the Holy of Holies is reported by Josephus, who apologetically downplayed the incident:

Caesar, finding himself unable to restrain the impetuosity of his frenzied soldiers and the fire gaining the mastery, passed with his generals within the building and beheld the holy place of the sanctuary and all that it contained…. (J.W. 6:260; Loeb)

Rabbinic tradition, on the other hand, greatly embellished Titus’ misdeeds in the Holy of Holies. A relatively restrained account of Titus’ profanation of the Holy of Holies is reported in a tannaic source:

רבי נחמיה אומר זה טיטוס הרשע בן אשת של אספסיינוס שנכנס לבית קדש הקדשים וגדר שתי פרכות בסייף ואמר אם אלוה הוא יבוא וימחה

[Where are their gods? ⟨Deut. 32:37⟩.] Rabbi Nehemyah says, “This is Titus the wicked, son of Vespasian’s wife, who entered the Holy of Holies and cut the two curtains with a sword and said, ‘If he is a god, let him come and destroy me!’” (Sifre Deut. §328 [ed. Finkelstein, 378-379]; cf. Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version B, §7)

According to this version, Titus not only profaned the Temple by entering the Holy of Holies, which was forbidden to all but the high priest on the Day of Atonement, the Roman general also blasphemed Israel’s God, mocking him and denying his divinity. In other versions, however, Titus is said to have violated the Temple by committing lewd acts in the Holy of Holies (b. Git. 56b). The way Titus’ intrusion into the Holy of Holies captured the Jewish imagination, and Mark’s peculiar grammar in Mark 13:14, according to which “the abomination of desolation” (neuter) is said to stand where he (masculine) does not belong, make this incident a strong candidate for “the abomination of desolation” the author of Mark had in mind when he made his Danielic revision to Jesus’ prophecy.

On the other hand, the sacrifice of the Roman soldiers to their standards within the Temple courts bears a stronger resemblance to Antiochus’ rededication of the Temple to Zeus, since both incidents involve idolatrous sacrifice within the Temple’s precincts. Josephus described the incident in the following manner:

The Romans, now that the rebels had fled [the Temple Mount] to the [upper] city, and the sanctuary itself and all around it were in flames, carried their standards into the temple court and, setting them up opposite the eastern gate, there sacrificed to them, and with rousing acclamations hailed Tiberius as imperator [a title awarded to victorious Roman generals]. (J.W. 6:316; Loeb)

The sacrifice to the Roman standards impressed itself on the church’s memory. Ephrem the Syrian (ca. 306-373) mentioned it in his Commentary on the Diatessaron:

[Let us now explain] this saying, When you will see the sign of its terrible destruction [Matt. 24:15]. [Jerusalem] was destroyed many times and then rebuilt, but here it is a question of its [total] upheaval and destruction and the profanation of its sanctuary, after which it will remain in ruins and fall into oblivion. The Romans placed standards representing an eagle within this temple just as [the prophet] had said, On the wings of impurity and ruination [Dan. 9:27]. (Commentary on the Diatessaron 18:12)[40]

It is possible that John Chrysostom (ca. 349-407) reflects a distorted memory of the sacrifice to the Roman standards when he wrote:

Βδέλυγμα δὲ τὸν ἀνδριαντα τοῦ τότε τὴν πόλιν ἑλόντος φησὶν, ὃ ὁ ἐρημώσας τὴν πόλιν καὶ τὸν ναὸν ἔστησεν ἔνδον⋅ διὸ καὶ ἐρημώσεως αὐτὸ καλεῖ. Εἶτα ἵνα μάθωσιν, ὅτι καὶ ζώντων ἐνίων αὐτῶν ταῦτα ἔσται, διὰ τοῦτο ἔλεγεν⋅ “ὅταν ἴδετε τὸ βδέλυγμα τῆς ἐρημώσεως.”

And by “abomination” [Matt. 24:15] He meaneth the statue of him who then took the city, which he who desolated the city and the temple placed within the temple, wherefore Christ calleth it, “of desolation.” Moreover, in order that they might learn that these things will be while some of them are alive, therefore He said, “When ye see the abomination of desolation.” (Homilies on the Gospel of Saint Matthew 75:2)[41]

It is possible, of course, that the author of Mark conflated Titus’ profanation of the Holy of Holies with the sacrifice to the Roman standards (and perhaps other events as well) in his imagination. What may have been crucial for the author of Mark was the fact that the Temple was profaned; the precise details—and undoubtedly there were conflicting rumors of how this was accomplished—may have been of secondary importance to him.

Numerous scholars raise an objection to identifying Mark’s “abomination of desolation” with either Titus’ profanation of the Holy of Holies or the sacrifice to the Roman standards on the Temple Mount, namely that by the time the Temple was profaned it would have been too late to flee the city.[42] But this objection is not as weighty as it appears. In the first place, it is simply untrue that it was too late to abandon the city by the time the Temple was destroyed. After the Temple Mount was captured the Romans still had to subdue the lower and upper cities, a feat that was not accomplished until a month after the Temple went up in flames. Josephus reports that desertions from the besieged city continued right through this period (see J.W. 6:318-322, 366-373).[43] In the second place, if, as we believe, the author of Mark revised Jesus’ prophecy after the destruction of the Temple, then it may not have mattered to the author of Mark whether or not flight from the city was possible or practical by the time the Temple had been destroyed. What concerned the author of Mark was not creating an accurate account of the destruction of Jerusalem as it actually happened. His aim was to give his community’s experience of the destruction an apocalyptic interpretation in the light of Daniel’s visions. If that goal required fudging the historical details, it was unlikely to have bothered the author of Mark, whose greatest talent was embellishing the Gospel narratives he inherited from Luke with “fresh” details.

חָרְבָּנָהּ (HR). In LXX most instances of ἐρήμωσις (erēmōsis, “desolation,” “state of lying waste”)[44] occur as the translation of words formed from the שׁ-מ-מ root.[45] However, references to the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple in Mishnaic Hebrew sources typically use the noun חָרְבָּן (ḥorbān, “destruction”; cf., e.g., m. Git. 8:5). While חָרְבָּן is not attested in MT, it does occur in DSS (CD A V, 20; 4QpsMosese [4Q390] 1 I, 8), which proves that it was current in the late Second Temple period. Since we prefer to reconstruct direct speech, including Jesus’ prophetic utterances, in a style resembling Mishnaic Hebrew, we have adopted חָרְבָּן for HR. Below is an example of חָרְבָּן with a feminine pronominal suffix:

מלמד שכיפר לה חורבנה

It teaches that her [i.e., Jerusalem’s—DNB and JNT] destruction [חוֹרְבָּנָהּ] atoned for her. (t. Ber. 1:15; Vienna MS)

L7-8 τὸ ῥηθὲν διὰ Δανιὴλ τοῦ προφήτου (Matt. 24:15). The author of Matthew clarified for his readers Mark’s cryptic reference to “the abomination of desolation” by adding “the one spoken of by Daniel the prophet.” The redactional character of this addition is evident from its similarity to the uniquely Matthean Scripture fulfillment formulae τότε ἐπληρώθη τὸ ῥηθὲν διὰ + personal name + τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος (“Then was fulfilled the thing spoken through + personal name + the prophet, saying…”; Matt. 2:17; 27:9) and ἵνα/ὅπως πληρωθῇ τὸ ῥηθὲν διὰ + personal name + τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος (“So that might be fulfilled the thing spoken through + personal name + the prophet, saying…”; Matt. 4:14; 8:17; 12:17; cf. Matt. 2:23; 13:35; 21:4).[46] While it is not certain whether the author of Mark thought that the abomination of desolation mentioned in Daniel referred to the events of 70 C.E. or merely prefigured them, it is clear that the author of Matthew thought that the prophecies of both Daniel and Jesus referred to eschatological events that were yet to be fulfilled and were therefore unrelated to the events of 70 C.E.[47]

Whereas the book of Daniel refrains from identifying Daniel as a prophet, Daniel is so identified not only in Matthew but also in ancient Jewish sources (cf. 4QFlorilegium [4Q174] 1 II, 3; Jos., Ant. 10:249, 268; cf. Seder Olam §20).[48]

L9 ἑστηκότα ὅπου οὐ δεῖ (Mark 13:14). Mark’s grammar in L9 is unusual. Whereas the gender of “the abomination of desolation” is neuter, the participle ἑστηκότα (hestēkota, “standing”), which modifies it, is masculine. While it is possible that this discrepancy is simply a grammatical mistake, it is, perhaps, more likely that the discrepancy is intentional. The author of Mark may have wished to signify by this gender discrepancy that the abomination of desolation was an individual (Titus?) or the image of an individual (the emperor? a tropaeum?).[49] Indeed, it may be that when the author of Mark summoned his readers to understand (L10) he was asking them to pay attention to the grammatical anomaly and to discern its significance. If so, the author of Matthew failed to discern it, since he removed Mark’s grammatical anomaly by replacing ἑστηκότα with the neuter form ἑστός (hestos, “standing”).[50]

The author of Matthew’s replacement of Mark’s ὅπου οὐ δεῖ (hopou ou dei, “where he must not”) with ἐν τόπῳ ἁγίῳ (en topō hagiō, “in a holy place”) is more specific, but not so specific as to leave us without questions.[51] Did the author of Matthew imagine that a pagan or Jewish temple would someday be reconstructed on the Temple Mount? Or does the lack of the definite article indicate that the author of Matthew was not thinking about the site of the Second Temple? Might the holy place he was thinking of be the site of Jesus’ crucifixion and/or burial?[52] Or was he afraid that some outside influence would impose itself upon the meeting place(s) of the Matthean community?[53]

L10 ὁ ἀναγινώσκων νοείτω (Mark 13:14). With the imperative “Let the reader understand!” the author of Mark interrupted Jesus’ speech in order to directly address his readers.[54] As we noted in the previous comment, it may be that the author of Mark wished his readers to take careful note of the grammatical awkwardness of his sentence in order that they might realize that by “the abomination of desolation” he referred to a particular individual (Titus?) or a particular individual’s image (the emperor’s?).[55] The author of Mark’s interruption may be an inadvertent admission of his editorial reworking of Jesus’ prophecy in light of Daniel’s visions, or it may simply be a clumsy attempt to retain a parallel to Luke’s imperative to know (L5) that Jerusalem’s desolation has come near.

The author of Matthew took over the appeal for understanding from Mark, but his editorial insertions in L7-8 altered its effect. Unlike Mark 13:14, where “Let the reader understand!” is a direct appeal from the author of Mark to the readers of his Gospel, in Matthew it is possible to construe the appeal as coming from Jesus: “Therefore, when you see the abomination of desolation, the one spoken of by Daniel the prophet, standing in a holy place—let the reader [i.e., of Daniel] understand….”[56] Thus it appears the author of Matthew, whether subconsciously or with full awareness,[57] assimilated Mark’s intrusive authorial remark into Jesus’ speech.

L11-12 τότε οἱ ἐν τῇ Ἰουδαίᾳ φευγέτωσαν εἰς τὰ ὄρη (Luke 21:21). If, as so many scholars suppose, the antecedent of αὐτῆς (avtēs, “of her”) in L13 is Jerusalem rather than Judea,[58] then the command “Then let the ones in Judea flee to the mountains” fits awkwardly in its Lukan context, intruding between “When you see Jerusalem surrounded” and “Let those inside her [i.e., Jerusalem] depart.”[59] Some scholars have cited this intrusive command in L11-12 as proof of Luke’s partial (if not total) dependence on Mark as a source for the prophecy of destruction and redemption in Luke 21.[60] For adherents to Lindsey’s hypothesis, however, Lukan dependence on Mark is not a satisfactory explanation. But neither can we ignore the apparent intrusiveness of L11-12 in their Lukan context.

We suspect it was the First Reconstructor who interpolated the command for Judeans to flee to the mountains. In so doing the First Reconstructor may have sought to make Jesus’ prophecy more widely applicable at a time prior to the Temple’s destruction when there were congregations of believers scattered throughout Judea and beyond. Congregations in Judea would have required instructions regarding how they should behave when the Roman legions advanced through their land, as Jesus had warned they would. The injunction in L11-12 satisfies that need.

Since we regard the command for Judeans to flee to the mountains as a redactional insertion from FR, we have omitted an equivalent to these lines in GR and HR.

The author of Mark picked up FR’s interpolated command to the Judeans from Luke, but he dispensed with the instructions for those caught up in the siege of Jerusalem retained in Luke 21:21 (L13-16). His reason for making this omission was his desire to insert his version of Lesson of Lot’s Wife (Mark 13:15-16) immediately following the command to the Judeans to flee to the mountains, which reminded him of the story of Lot’s escape from Sodom, where an angel commands Lot, εἰς τὸ ὄρος σῴζου (eis to oros sōzou, “Get safely to the mountain!”; Gen. 19:17).[61] Since the instructions to Jerusalem’s residents would have impinged upon the connection the author of Mark saw between the command to the Judeans and Lesson of Lot’s Wife, the author of Mark had no alternative but to dispense with the instructions to those caught up in Jerusalem’s siege.

Some scholars detect in Mark’s scenario, in which seeing the abomination of desolation leads to taking flight to the hills, a pattern established in the days of the Hasmonean revolt against the Seleucid Empire, when Antiochus IV set up the abomination of desolation in the Temple (1 Macc. 1:54) and the Hasmoneans and their followers took to the hills (1 Macc. 2:28).[62] However, in 1 Maccabees there is no direct connection between the abomination of desolation’s erection in the Temple and the flight of the rebel Jews. The flight of Mattathias and his followers was a reaction not to the abomination of desolation but to the murder of the king’s messengers, an action that made Mattathias and his men wanted criminals in the eyes of the Seleucid state. Since 1 Maccabees does not establish a cause and effect relationship between the abomination of desolation and the Hasmoneans’ flight to the hills, 1 Maccabees can hardly be the source of the pattern in Mark of seeing the abomination of desolation and taking flight to the hills.

L13 καὶ οἱ ἐν μέσῳ αὐτῆς (GR). We believe the original antecedent of αὐτῆς (avtēs, “of her”) in L13 was Ἰερουσαλήμ (Ierousalēm, “Jerusalem”) in Luke 21:20. When the First Reconstructor inserted the command to the Judeans to flee to the hills, however, the antecedent became Ἰουδαία (Ioudaia, “Judea”). By making Ἰουδαία the antecedent of αὐτῆς the First Reconstructor transformed Jesus’ instructions to the people caught up in the siege of Jerusalem into a universally applicable instruction to evacuate the entire province: “Let the ones inside her [i.e., Judea] depart. And let not the ones in the [other] countries enter her [i.e., Judea].”[63] In Anth. οἱ ἐν μέσῳ αὐτῆς (hoi en mesō avtēs, “the ones inside her”) referred to the people who might find themselves within the walls of Jerusalem—whether permanent residents, pilgrims or refugees—when the siege began.[64]

וּמִי שֶׁבְּתוֹכָהּ (HR). In Lesson of Lot’s Wife, L2 and L8, we similarly reconstructed the definite article with -מִי שֶׁ (mi she-, “who that,” “whoever”).

On reconstructing ἐν μέσῳ (en mesō, “in the middle of”) with בְּתוֹךְ (betōch, “in the middle of”), see “The Harvest Is Plentiful” and “A Flock Among Wolves,” Comment to L50.

L14 ἐκχωρείτωσαν (GR). The presence of the verb ἐκχωρεῖν (ekchōrein, “to emigrate,” “to leave a country”) in Anth. may have facilitated (and partly inspired) the First Reconstructor’s transformation of the Jerusalem-centric instructions into a set of universally applicable commands addressed to those within and without Judea.

יִבְרַח (HR). The verb ἐκχωρεῖν is quite rare in LXX,[65] but there is an example in Amos where ἐκχωρεῖν occurs as the translation of בָּרַח (bāraḥ, “flee”):

וַיֹּאמֶר אֲמַצְיָה אֶל עָמוֹס חֹזֶה לֵךְ בְּרַח לְךָ אֶל אֶרֶץ יְהוּדָה

And Amaziah said to Amos, “O seer, go! Take yourself off to the land of Judah!” (Amos 7:12)

καὶ εἶπεν Αμασιας πρὸς Αμως Ὁ ὁρῶν, βάδιζε ἐκχώρησον εἰς γῆν Ιουδα

And Amaziah said to Amos, “O seer, go! Emigrate to the land of Judah!” (Amos 7:12)

L15 καὶ οἱ ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ (GR). We suspect that the words ταῖς χώραις (tais chōrais, “the countries,” “the regions”) were introduced by the First Reconstructor as a replacement for a different phrase in Anth. Our suspicion arises from the apparent wordplay between the verb ἐκχωρεῖν (“to leave a country”) in L14 and the noun χώρα (chōra, “country,” “region”) in L15 and from the difficulty of reconstructing ἐν ταῖς χώραις (en tais chōrais, “in the countries”) in the present context.[66] If the commands in L13-16 are to be understood as addressed to two groups—those inside the walls of Jerusalem at the onset of the siege (L13-14) and those near Jerusalem at the onset of the siege but beyond the city walls (L15-16)—then perhaps where Luke 21:21 now reads οἱ ἐν ταῖς χώραις (“the ones in the countries”) Anth. read οἱ ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ (hoi en tō agrō, “the ones in the field”). In Hebrew sources “city” and “field” are a common pair of opposites,[67] and ἀγρός (agros, “field”) is the standard Greek equivalent of שָׂדֶה (sādeh, “field”).[68] Moreover, the semantic ranges of ἀγρός (“field”) and χώρα (“country”) overlap,[69] so replacing οἱ ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ (“those in the field”) with οἱ ἐν ταῖς χώραις (“those in the countries”) would probably not have been too great a stretch for a Greek redactor like the First Reconstructor.

Supposing that Anth. read οἱ ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ (“the ones in the field”) in L15 also provides one more reason why the author of Mark might have felt that Lesson of Lot’s Wife was a fitting substitute for the instructions in L13-16, since Lesson of Lot’s Wife instructs “the one in the field” not to turn back (Matt. 24:18 ∥ Mark 13:16 ∥ Luke 17:31).

For all these reasons we have adopted καὶ οἱ ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ (“and the ones in the field”) in L15 for GR.

וּמִי שֶׁבַּשָּׂדֶה (HR). On reconstructing the definite article ὁ (ho, “the [one]”) with -מִי שֶׁ (mi she-, “whoever”), see above, Comment to L13.

On reconstructing ἀγρός (agros, “field”) with שָׂדֶה (sādeh, “field”), see Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl, Comment to L4.[70] In the present context, “whoever is in the field” would refer to anyone who was near Jerusalem but caught outside the city walls at the time when the siege commenced.

L16 μὴ εἰσερχέσθωσαν εἰς αὐτήν (GR). As was the case with αὐτῆς (“of her”) in L13, the antecedent of αὐτήν (avtēn, “her”) in Luke 21:21 is “Judea.” Accordingly, in Luke’s version of Yerushalayim Besieged the command in L15-16 means that no one outside Judea should enter the province once the siege of Jerusalem was under way. But as we discussed above (see Comment to L13), the original antecedent of the feminine pronouns in Luke 21:21 was probably “Jerusalem.” The change of the antecedent to “Judea” likely reflects the work of the First Reconstructor.

The First Reconstructor’s changes to Yerushalayim Besieged make sense for a time when there were close contacts between the believing communities located in Judea and around the Roman world. Under such conditions it would be necessary to warn the believing communities from beyond Judea not to send aid to their sister communities in Judea or to join the war effort against the Romans. Close contact between the Judean congregations and those outside the land of Israel existed during the career of the apostle Paul and are well documented in Acts. As we have argued elsewhere, the redactional changes the First Reconstructor made to Yerushalayim Besieged and other parts of Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption provide important clues for the dating of FR, which we believe was completed prior to the destruction of the Temple.[71]

In Anth. the instructions in L15-16 meant that no one in the vicinity of Jerusalem caught outside the city walls at the onset of the siege should attempt to seek refuge within Jerusalem.

אַל יִכָּנֵס לָהּ (HR). On reconstructing εἰσέρχεσθαι (eiserchesthai, “to enter”) with נִכְנַס (nichnas, “enter”), see Sending the Twelve: Conduct in Town, Comment to L100. The verb נִכְנַס normally takes the preposition -לְ (le–, “to”), which is equivalent to the preposition εἰς (eis, “into”) in the Greek text of Luke 21:21 (L16). The following excerpt from the Mishnah illustrates how entering a city was expressed in Mishnaic Hebrew:

הַנִּכְנַס לָעִיר וְאֵינוּ מַכִּיר אָדָם שָׁם

The one who enters the city but is not acquainted with anyone there…. (m. Dem. 4:6)

For the people of his time Jesus’ advice in L13-16 would have sounded counterintuitive. Usually in the face of an advancing army the people would take refuge in fortified cities, and Jerusalem was protected (or so it was believed) not only by its walls and other defenses, but by the divine presence that dwelt within it.[72] However, Jesus—like the prophet Jeremiah before him—warned that the people should not place their confidence in Jerusalem’s fortifications or take divine protection for granted. Jerusalem was doomed on account of the people’s rejection of the Kingdom of Heaven. The redemption that had been so close was now withdrawn until the times of the Gentiles will have reached their completion.

L17-25 As we discussed above in Comment to L11-12, the author of Mark injected his version of Lesson of Lot’s Wife into Abomination of Desolation (his version of Yerushalayim Besieged) as a replacement for the instructions given in Luke 21:21 (L13-16). This he did because the command for the Judeans to flee to the hills reminded the author of Mark of the story of Lot, in which he too was commanded to seek refuge in the hills, and because the advice that those in the field should not enter the city resembled the command in Lesson of Lot’s Wife that a person in the field should not look back. The author of Matthew followed Mark’s reworked version of Jesus’ prophecy.

Since we have reconstructed the contents of L17-25 elsewhere, we refer readers to the LOY segment Lesson of Lot’s Wife for a detailed discussion of this pericope.

L26-29 There is no direct parallel to Luke 21:22 (L26-29) in Mark or Matthew, although Luke’s “these are days of vengeance” (L26-27) is roughly equivalent to “those days will be trouble” in Mark 13:19 (L37-39). Since we believe it is Luke’s version of Yerushalayim Besieged that most closely resembles the version in Anth., we have included reconstructions of L26-29 in GR and HR.

L26 שֶׁיְּמֵי (HR). On reconstructing ὅτι (hoti, “that,” “because”) with the relative pronoun -שֶׁ (she-, “who,” “that”), which could also be used with the sense “because,” see Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, Comment to L31.

On reconstructing ἡμέρα (hēmera, “day”) with יוֹם (yōm, “day”), see Choosing the Twelve, Comment to L1.

L27 נָקָם אֵלּוּ (HR). In LXX the phrase αἱ ἡμέραι τῆς ἐκδικήσεως (hai hēmerai tēs ekdikēseōs, “the days of vengeance”) occurs as the translation of יְמֵי הַפְּקֻדָּה (yemē hapequdāh, “the days of visitation”) in Hos. 9:7.[73] More often in LXX, however, the noun ἐκδίκησις (ekdikēsis, “vengeance”) occurs as the translation of נָקָם (nāqām, “vengeance”) or נְקָמָה (neqāmāh, “vengeance”).[74] The phrase ἡμέρα ἐκδικήσεως (hēmera ekdikēseōs, “day of vengeance”) occurs in Jer. 26[46]:10 as the translation of יוֹם נְקָמָה (yōm neqāmāh, “day of vengeance”) with respect to the defeat of Pharaoh Neco by Nebuchadnezzar in the battle of Carchemish. The phrase יוֹם נָקָם (yōm nāqām, “day of vengeance”) is more common, appearing in the Hebrew Scriptures (Isa. 34:8; 61:2; 63:4; Prov. 6:34) and DSS (1QS IX, 23; X, 19; 1QM VII, 5; XV, 3), often with reference to an eschatological day of judgment. Strangely enough, the LXX translators never rendered יוֹם נָקָם as ἡμέρα ἐκδικήσεως. All this leaves us with some uncertainty as to how ἡμέραι ἐκδικήσεως (“days of vengeance”) ought to be reconstructed in L26-27. We have settled on יְמֵי נָקָם (yemē nāqām, “days of vengeance”) because it is closest to the most common expression for “day of vengeance,” יוֹם נָקָם. Supposing that יְמֵי נָקָם is the correct reconstruction, we might imagine that Jesus used this phrase to hint that the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple was not identical to the Day of Vengeance. A long time would pass between the vengeance meted out to Jerusalem and the final day of reckoning.

L28 כְּדֵי לְקַיֵּים (HR). In LXX the verb πιμπλάναι (pimplanai, “to fill”) usually occurs as the translation of the root מ-ל-א in its various stems.[75] The correspondence between πιμπλάναι in LXX and מ-ל-א explains why Delitzsch, in his Hebrew translation of the New Testament, rendered τοῦ πλησθῆναι πάντα τὰ γεγραμμένα (“to be fulfilled all the things written”) in Luke 21:22 as לְמַלֹּאת כָּל הַכָּתוּב (“to fulfill all the Scripture”).[76] Delitzsch’s translation, however, is unidiomatic. In rabbinic sources we never encounter verbs from the root מ-ל-א used in reference to the fulfillment of Scripture. Rabbinic sources use the verbs קִיֵּים (qiyēm, “carry out [a task],” “fulfill”) and נִתְקַיֵּים (nitqayēm, “be realized,” “be fulfilled”) for the fulfillment of Scripture.[77] Although Luke’s text has a passive infinitive, we have not adopted לְהִתְקַיֵּים (lehitqayēm, “to be fulfilled”) for HR. “In order that the Scriptures might be fulfilled” would have to be expressed as כְּדֵי שֶׁיִּתְקַיֵּימוּ כָּל הַכְּתוּבִים; reconstructing τοῦ πλησθῆναι πάντα τὰ γεγραμμένα as כְּדֵי לְהִתְקַיֵּם כָּל הַכְּתוּבִים strikes us as just as unidiomatic as Delitzsch’s translation. Supposing that Luke’s infinitive reflects an infinitive construct in the underlying Hebrew text, כְּדֵי לְקַיֵּים אֶת כָּל הַכְּתוּבִים (kedē leqayēm ’et kol haketūvim, “in order to fulfill all the Scriptures”) appears to be the best option for HR. In support of our reconstruction is the fact that passive forms of πιμπλάναι in LXX often occur as the translation of verbs in active stems.[78] For example:

וּכְבוֹד יי מָלֵא אֶת הַמִּשְׁכָּן

…and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle. (Exod. 40:34)

καὶ δόξης κυρίου ἐπλήσθη ἡ σκηνή

…and the tabernacle was filled with the glory of the Lord. (Exod. 40:34)

וּמֵעֶיךָ תְמַלֵּא אֵת הַמְּגִלָּה הַזֹּאת…and fill your stomach with this scroll…. (Ezek. 3:3)

καὶ ἡ κοιλία σου πλησθήσεται τῆς κεφαλίδος ταύτης

…and your stomach will be filled with this scroll…. (Ezek. 3:3)

וּמָלְאוּ אֶת הָאָרֶץ חָלָל

…and they will fill the land with the slain. (Ezek. 30:11)

καὶ πλησθήσεται ἡ γῆ τραυματιῶν

…and the land will be filled with the wounded. (Ezek. 30:11)

L29 אֶת כָּל הַכְּתוּבִים (HR). On reconstructing πᾶς (pas, “all,” “every”) with כָּל (kol, “all,” “every”), see Demands of Discipleship, Comment to L32.

The use of τὸ γεγραμμένον (to gegrammenon, “the [thing] written”) with reference to Scripture is unique to Luke among the Synoptic Gospels (Luke 18:31; 20:17; 21:22; 22:37; 24:44). Significantly, however, this use of τὸ γεγραμμένον is absent in Acts,[79] which suggests that in Luke’s Gospel this usage of τὸ γεγραμμένον is a reflection of Luke’s sources rather than of Lukan redaction.[80] As Buth and Kvasnica have noted, Luke’s use of τὸ γεγραμμένον—a substantival passive participle—is an exact grammatical parallel to the Hebrew passive participle הַכָּתוּב (hakātūv, “the [thing] written”).[81] In rabbinic sources הַכָּתוּב usually occurs with a meaning roughly parallel to “the Scripture verse” or “the Scripture passage.” Thus we frequently encounter the phrase הַכָּתוּב שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה (hakātūv shebatōrāh, “the thing written that is in the Torah,” i.e., “the Torah verse”),[82] and we find statements such as the following:

ר′ יִשְׁמָעֵאל אוֹמֵ′ כָּתוּב אֶחָד אוֹ′ הַקְדֵּשׁ וְכָתוּב אַחֵד אוֹמֵ′ אַל תַּקְדֵּשׁ

Rabbi Yishmael says, “One written thing [i.e., verse—DNB and JNT] says, Sanctify! [Deut. 15:19], and another written thing [i.e., verse—DNB and JNT] says, You must not sanctify! [Lev. 27:26]….” (m. Arach. 8:7)

Accordingly, if τὰ γεγραμμένα (ta gegrammena, “the things written”) in Luke 21:22 reflects הַכְּתוּבִים (haketūvim, “the things written”) in the underlying Hebrew text, the meaning of הַכְּתוּבִים in Yerushalayim Besieged is probably closer to “the Scripture passages” or “the Scripture verses” than “the Scriptures.” We find a parallel usage of הַכְּתוּבִים in this sense in the following example:

ויהי בנסוע הארון ויאמר משה, מלמד שהיו נוסעין על פי משה: כת′ ויהי בנסוע הארון ויאמר משה ובנחה יאמר שובה י″י וכת′ על פי י″י יחנו ועל פי י″י יסעו (במד′ ט כג) וכי היאך אפשר לקיים כל הכתובים הללו הא כיצד—בזמן שהיו נוסעין היה עמוד הענן נעקר ממקומו על פי המקום ולא היה לו רשות להלוך עד שיאמר לו משה נמצאת מקיים על פי י″י ועל פי משה

And when the ark would set out Moses would say [Num. 10:35]. This teaches that they would set out at Moses’ command. It is written, And when the ark would set out Moses would say…and when it rested he would say, “Return, O Lord…” [Num. 10:35-36], but it is also written, At the Lord’s command they would camp, and at the Lord’s command they would set out [Num. 9:23]. So how is it possible to establish all these verses [לְקַיֵּים כָּל הַכְּתוּבִים הַלָּלוּ]? How? When they were setting out the pillar of cloud would be uprooted from its place at the command of the Omnipresent One, but it would not have authority to go until Moses would speak to it. The result is “at the Lord’s command” and “at Moses’ command” is established. (Sifre Num. Zuta, BeHa‘alotecha 10:35 [ed. Horovitz, 266-267])

As we discussed above in Comment to L3, one of the Scripture passages concerning the destruction of Jerusalem that Jesus almost certainly had in mind was Zech. 14:2.

Like Jesus, Josephus claimed to know of scriptural passages that prophesied the destruction of Jerusalem without citing specific verses (cf. J.W. 6:109).

L30 οὐαὶ (GR). The absence of the conjunction δέ (de, “but”) in Luke’s version of Yerushalayim Besieged looks authentic. The author of Mark probably added the δέ when he transitioned from Lesson of Lot’s Wife back to his sources for Yerushalayim Besieged (viz., Luke and Anth.). The author of Matthew copied the δέ in L30 from Mark.

אִי (HR). On reconstructing οὐαί (ouai, “Woe!”) with אִי (’i, “Woe!”), see Woes on Three Villages, Comment to L5.

L31-33 Since in L31-33 there is complete verbal agreement among all three Synoptic Gospels, and since the Greek in these lines reverts easily to Hebrew (see below), it is likely that the Synoptic Gospels have reproduced Anth.’s wording exactly. Therefore, no further discussion of GR in L31-33 is required.

L31 לָעוּבָּרוֹת (HR). In LXX the phrase ἐν γαστρὶ ἔχειν (en gastri echein, “to have in the belly”)[83] typically occurs as the translation of the verb הָרָה (hārāh, “conceive”) or the adjective הָרָה (hārāh, “pregnant”), which was often used substantivally as “pregnant woman.”[84] Had we wished to reconstruct Jesus’ words in a biblicizing style of Hebrew, the substantival plural adjective הָרוֹת (hārōt, “pregnant women”) would have been the right choice.[85] However, in Mishnaic Hebrew “pregnant woman” was expressed either as מְעוּבֶּרֶת (me‘ūberet), a passive participle used substantivally, or עוּבָּרָה (‘ūbārāh, “pregnant woman”; var. עוֹבָרָה [‘ōvārāh]), a noun.

Examples of מְעוּבֶּרֶת include:

ר′ אֱלִיעֶזֶר אוֹמֵ′ אַרְבַּע נָשִׁים דַּיָּין שַׁעְתָן בְּתוּלָה וּמְעוּבֶּרֶת וּמֵנִיקָה וּזְקֵינָה

Rabbi Eliezer says, “There are four [classes of] women whose time [of experiencing a discharge] is sufficient for them [to be deemed impure]: a virgin, and a pregnant woman [וּמְעוּבֶּרֶת], and a nursing mother, and a postmenopausal woman.” (m. Nid. 1:3)

השוכר את החמור…להרכיב אשה מרכיב אשה עליה בין מעוברת ובין מניקה

The one who hires a donkey…to give a woman a ride, he gives the woman a ride on it whether she is a pregnant woman [מְעוּבֶּרֶת] or whether she is a nursing mother. (t. Bab. Metz. 7:10; Vienna MS)

שלש נשים משמשות במוך קטנה מעוברת ומניקה

Three [classes of] women have sexual relations with a contraceptive: a minor, a pregnant woman [מְעוּבֶּרֶת] and a nursing mother. (t. Nid. 2:6; Vienna MS)

Examples of עוּבָּרָה (var. עוֹבָרָה) include:

עֹבָרָה שֶׁהֵארִיחָה מַ

נאֲכִילִין אוֹתָם עַד שַׁתָּשׁוּב נַפְשָׁהּA pregnant woman [עֹבָרָה] who smells [food on the Day of Atonement and is overcome by it—DNB and JNT]: they feed them until her soul is refreshed. (m. Yom. 8:5)

העוברות והמניקות מתענות בתשעה באב וביום הכפורים ובשלש תעניות השניות של צבור ושאר תעניות לא היו מתענות

Pregnant women [הָעוּבָּרוֹת] and nursing mothers fast during the ninth of Av and on the Day of Atonement and during the three fasts of the second round of public fasting, but the rest of the fasts they would not fast. (t. Taan. 2:14)

Since we prefer to reconstruct Jesus’ words in a Mishnaic style of Hebrew, either מְעוּבֶּרֶת or עוּבָּרָה would be acceptable for HR. We have chosen the latter partly under the influence of the following woe pronounced in the time of Rabbi Yehudah ha-Nasi (ca. 200 C.E.):

אִי לָכֶם חַיּוֹת שֶׁבְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל אִי לָכֶם עֻבָּרוֹת שֶׁבְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל

Woe to you women in childbirth who are in the land of Israel. Woe to you pregnant women [עֻבָּרוֹת] who are in the land of Israel! (Gen. Rab. 96:5 [ed. Merkin, 4:176]; cf. Theodor-Albeck, 3:1199)

L32 וְלַמֵּנִיקוֹת (HR). The examples cited in the previous comment provide ample evidence for the use of מֵנִיקָה (mēniqāh, “nursing mother”) in rabbinic sources and for its pairing with both מְעוּבֶּרֶת and עוּבָּרָה.[86]

In LXX the participle θηλαζούσα (thēlazousa, “lactating”) occurs once as the translation of מֵנִיקָה (“lactating”):

וַיָּלֶן שָׁם בַּלַּיְלָה הַהוּא וַיִּקַּח מִן הַבָּא בְיָדוֹ מִנְחָה לְעֵשָׂו אָחִיו׃ עִזִּים מָאתַיִם וּתְיָשִׁים עֶשְׂרִים רְחֵלִים מָאתַיִם וְאֵילִים עֶשְׂרִים׃ גְּמַלִּים מֵינִיקוֹת וּבְנֵיהֶם שְׁלֹשִׁים

And he spent the night there that night. And he took from what he brought with him a gift for his brother Esau: two hundred nanny goats and twenty billy goats, two hundred ewes and twenty rams, thirty lactating camels [LXX: καμήλους θηλαζούσας] and their young…. (Gen. 32:14-16)

In addition, there are multiple examples of θηλάζειν (thēlazein, “to give suck,” “to suckle”) that occur as the translation of הֵנִיקָה (hēniqāh, “give suck,” “breastfeed”).[87]

L33 בְּאוֹתָם הַיָּמִים (HR). On reconstructing ἐκεῖνος (ekeinos, “that”) with אֵת + third-person pronominal suffix, see Calamities in Yerushalayim, Comment to L14.

On reconstructing ἡμέρα (hēmera, “day”) with יוֹם (yōm, “day”), see Comment to L26 above.

Josephus gave an account of the miseries women and children endured when attempting to flee a besieged town:[88]

At nightfall John [of Gishala], seeing no Roman guard about the town, seized his opportunity and, accompanied not only by his armed followers but by a multitude of non-combatants with their families, fled for Jerusalem. For the first twenty furlongs he succeeded in dragging with him this mob of women and children,…but after that point as he pushed on they were left behind, and dreadful were their lamentations when thus deserted…. Many strayed off the track, and on the highway many were crushed in the struggle to keep ahead. Piteous was the fate of the women and children, some making bold to call back their husbands or relatives and imploring them with shrieks to wait for them. But John’s orders prevailed: “Save yourselves,” he cried, “and flee where you can have your revenge on the Romans for any left behind, if they are caught.” So this crowd of fugitives struggled away, each putting out the best strength and speed he had. (J.W. 4:106-111; Loeb)

While we must be wary of Josephus’ tendentious villainization of John of Gishala and his flair for the dramatic, the inability of women and children to keep up with the men when fleeing from the enemy was probably no exaggeration.

Jesus’ compassionate lamentation for the fate of the pregnant women and nursing mothers caught up in the misfortunes of Jerusalem illustrates his enduring solidarity with the Jewish people despite his gloomy predictions of divine judgment and national catastrophe.

L34-36 The command to pray that the disaster coming upon Jerusalem not take place in the winter (Mark-Matt.) or on the Sabbath (Matt.) is absent in Luke’s version of Yerushalayim Besieged. There are scholars who view this command as having originated prior to the events of 70 C.E., arguing that 1) after the events had already taken place there was no longer any point in praying about when those events might unfold,[89] and that 2) if original, the concern about the Sabbath reflects a Jewish or Jewish-Christian viewpoint more likely to have been held prior to the Temple’s destruction.[90] Some scholars believe that the prophecy concerning the abomination of desolation preserved in Mark 13:14-20 was originally composed in response to the crisis in 40 C.E. when the emperor Gaius Caligula issued an order to have his statue erected in Jerusalem’s Temple. Fears that the emperor’s edict would be carried out in the winter of 40-41 C.E. were only quelled by the emperor’s assassination on 24 January 41 C.E. According to this view, the command to pray that the abomination of desolation not appear in the winter reflects the original prophecy’s composition sometime prior to Caligula’s assassination.[91] The incorporation of this command in Mark’s Gospel along with the rest of the abomination of desolation prophecy is then cited as evidence for a pre-70 C.E. date for the composition of Mark, since the author of Mark would surely have eliminated the command to pray that the crisis not happen in winter if he had known that the actual siege of Jerusalem and the destruction took place in the spring and summer of 70 C.E.

We, of course, look at the command in Mark 13:18 ∥ Matt. 24:20 differently. Far from betraying ignorance of the events of 70 C.E., we believe the author of Mark added the command to pray that the crisis might not happen in winter precisely because he knew the entire course of the siege took place in the spring and summer of 70 C.E.[92] By adding this command the author of Mark was able to bolster Jesus’ image as an accurate prognosticator of future events and to enhance Jesus’ status as a Lord who is able to grant the prayers of the elect (cf. Mark 13:20). In other words, the author of Mark wished to convince his readers that because Jesus possessed miraculous foreknowledge, Jesus was able to instruct his followers to pray that the disaster not strike in winter, and that because God has delegated to Jesus the authority to grant his followers’ requests, the disaster ended up taking place not in winter but in the spring and summer. By enhancing Jesus’ credentials as a prognosticator and by highlighting Jesus’ ability to grant prayers, the author of Mark sought to instill in his readers greater confidence that the parts of Jesus’ prophecy that had yet to be fulfilled would happen just as Jesus predicted, and that through it all Jesus could be relied upon to preserve them from danger.[93]

Matthew’s reference to the Sabbath we regard not as an original part of Jesus’ command the author of Mark had omitted,[94] but as a further embellishment, which the author of Matthew added to the command he copied from Mark. We will discuss further reasons for regarding the content of L34-36 as secondary in the Comments below.

L34-35 προσεύχεσθε δὲ ἵνα μὴ γένηται (Mark 13:18). There is no particular difficulty in reconstructing Mark’s imperative προσεύχεσθε (prosevchesthe, “Pray!”) as הִתְפַּלְּלוּ (hitpalelū, “Pray!”).[95] Clauses including ἵνα + subjunctive, on the other hand, are often the product of Markan redaction.[96] As we have discussed above, we regard the command to pray as a Markan addition.

ἵνα μὴ γένηται ἡ φυγὴ ὑμῶν (Matt. 24:20). By appending the words ἡ φυγὴ ὑμῶν (hē fūgē hūmōn, “your flight”) to the end of L35, the author of Matthew supplied the command to pray with greater specificity, but in so doing the author of Matthew also changed the meaning of the command in a way that creates logical inconsistencies in Matthew’s version of the pericope.

In Mark the unstated antecedent of “it” in the phrase “pray that it may not happen in winter” is either the appearance of the abomination of desolation or the totality of the crisis caused by its appearance.[97] This was an event over which the people addressed by the command to pray had no control. It therefore makes sense that the addressees should pray to God about the timing of these events, since God is ultimately in control of everything. Likewise, the relatively long period of time indicated in Mark, “the winter,” makes sense. The people’s hardships would be increased if the abomination of desolation appeared at any time during the winter. Winter would make flight more difficult because of the cold and muddy roads, and provisions would be scarce.

The addition of “your flight” in Matthew changes the equation, because unlike the appearance of the abomination of desolation, the addressees are able to control the timing of their flight. If the abomination of desolation made its appearance on the Sabbath, the addressees could make their escape as soon as the Sabbath had ended. True, Matthew’s version of Jesus’ prophecy emphasizes the need for urgent flight, but the decision to flee remains firmly in the power of the addressees. Therefore, there is strictly no need to pray that the flight may not happen on the Sabbath: they do not need to pray that God will control their decision making.[98] Nevertheless, the Sabbath reference in L36 appears to be inseparable from the addition of “your flight” in L35, for without the addition of “your flight” in L35 the Sabbath reference is meaningless. The abomination of desolation could hardly have been more abominable or more desolating if it appeared on the Sabbath as opposed to any other day, therefore it is unlikely that “on the Sabbath” was omitted by the author of Mark. Rather, it appears the author of Matthew added “on the Sabbath” because he (mistakenly) believed that for Jews flight on the Sabbath would be difficult or even impossible.

L36 χειμῶνος μηδὲ σαββάτῳ (Matt. 24:20). The author of Matthew’s additions of “your flight” in L35 and “or on the Sabbath” in L36 should probably change the way we understand the noun χειμών (cheimōn). In Mark 13:18 χειμών probably means “winter,”[99] but the same noun can also mean “storm.”[100] Since storms are of relatively short duration, this sense of χειμών makes a better pair with “the Sabbath” than “winter,” so “storm” may be the meaning the author of Matthew intended.[101]

We have already stated our opinion that “or on the Sabbath” is a Matthean addition. But why would the author of Matthew want to make this change? Some scholars propose that “or on the Sabbath” was added for the sake of Jewish believers in Matthew’s audience who would have been reluctant to violate the Sabbath for any reason.[102] This explanation is unsatisfactory, however, since Matthew’s Gospel clearly presents Jesus as willing to suspend the usual restrictions of the Sabbath in case of emergencies involving danger to human life. If, as we must presume, the Jewish members of the Matthean community accepted Jesus’ teachings as presented in Matthew’s Gospel, why should they have experienced difficulty applying Jesus’ teachings to their personal safety? It is especially difficult to suppose that, with Jesus as their teacher, the Jewish Christians in Matthew’s audience had come to adopt a more stringent attitude toward the Sabbath than the wider Jewish community.[103] We know from multiple sources that mainstream Jews of the first century were of the opinion that it was permissible to take up arms in self-defense on the Sabbath. This ruling was determined during the Jewish revolt against Antiochus IV (1 Macc. 2:39-41), it became the official line of the ruling Hasmoneans, Josephus portrayed it as the normative opinion during the first century (Ant. 14:63),[104] and this opinion is reiterated in rabbinic sources.[105] Indeed, we do not find a dissenting opinion in any ancient Jewish source after the Hasmoneans made their decision.[106] If by the first century a general consensus had been reached that fighting in self-defense was permissible on the Sabbath, then clearly that consensus also permitted avoiding a fight by fleeing from danger on the Sabbath.[107]

Rather than reflecting Jewish concerns, as so many scholars suppose,[108] we believe the author of Matthew’s addition of “or on the Sabbath” reflects general Gentile ignorance of Jewish customs and particular Matthean disdain for the Jewish people.[109] Whereas in Mark “Pray that it might not happen in winter” served to highlight Jesus’ ability as a prognosticator, in Matthew “Woe to the pregnant women and nursing mothers! Pray that your flight may not be in a storm or on the Sabbath!” became a callous taunt. Such a transformation is in keeping with the attitudes of the author of Matthew, who made the entire Jewish people culpable for Jesus’ death by their self-imprecation “His blood be upon us and upon our children!” (Matt. 27:25). Evidently the author of Matthew was under the same misapprehension about the Jewish people as were other Gentile authors who mocked the Jews for allowing Jerusalem to fall into enemy hands because of their “superstitious addiction” to the Sabbath. Thus Agatharchides of Cnidus blamed Jerusalem’s subjection to the Ptolemaic Empire in the days of Ptolemy I Soter on Sabbath observance.[110] Cassius Dio blamed Jewish Sabbath observance for Pompey’s conquest of Jerusalem in 63 B.C.E.[111] And likewise, Frontinus blamed Sabbath observance for the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 C.E.[112] Plutarch, too, ascribed the fall of Jerusalem into enemy hands to Jewish Sabbath observance, but he did not specify to which capture of the city he referred.[113] The author of Matthew’s addition of “Pray that your flight may not be…on the Sabbath” does not blame Jewish Sabbath observance for the fall of Jerusalem, but it does disparage the Jewish people for being so foolish as to allow the Sabbath to prevent them from saving themselves.

L37 ἔσται γὰρ (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreement to write “for he/she/it will be,” as opposed to Mark’s “for they will be,” virtually assures that ἔσται γάρ (estai gar, “for he/she/it will be”) was the reading of Anth. The author of Mark changed the third person singular verb to a third person plural because he wished to change the subject from ἀνάγκη (anankē, “duress”; L39) to αἱ ἡμέραι ἐκεῖναι (hai hēmerai ekeinai, “those days”; L38) for reasons we will discuss below.