Matt. 13:44-46

(Aland 132; Huck 101; Crook 154)[1]

Revised: 24 October 2022

[וַיִּמְשׁוֹל לָהֶם מָשָׁל לֵאמֹר] לְמַה אֲדַמֶּה מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם לְמַטְמוֹן בַּשָּׂדֶה שֶׁמָּצָא אָדָם וְטָמַן אֹתוֹ וּמִשִׂמְחָתוֹ הָלַךְ וּמָכַר כֹּל מַה שֶּׁהָיָה לוֹ וְלָקַח אֹתָהּ הַשָּׂדֶה וְעוֹד אָמַר לְמַה אֲדַמֶּה מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם לְאִישׁ תַּגָּר הַמְּבַקֵּשׁ מַרְגָּלִיּוֹת טוֹבוֹת וּכְשֶׁמָּצָא מַרְגָּלִית אַחַת יְקָרָה הָלַךְ וּמָכַר כֹּל מַה שֶּׁהָיָה לוֹ וְלָקַח אוֹתָהּ

Then Yeshua told them this parable: “What comparison can I make to illustrate the worth of belonging to my band of disciples? It’s like a man who stumbled upon buried treasure in a field. What did he do? He reburied it, and in his excitement he sold everything he owned to get enough money to buy the field and obtain the treasure.”

He said once more, “What other comparison can I make to illustrate the worth of belonging to my band of disciples? It’s like a merchant who spent his life buying and selling rare pearls. What did he do when he chanced upon a priceless pearl? He sold everything he owned to get enough money to buy it.”[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables click on the link below:

| “Cost of Entering the Kingdom of Heaven” complex |

| Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven ・ Demands of Discipleship ・ Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables |

Story Placement

The author of Matthew included the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables in the third major discourse of his Gospel (Matt. 13:3-53). Within this discourse, which consists almost entirely of parables, the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables appear after the Interpretation of the Wheat and Weeds parable (Matt. 13:36-43). Perhaps the connection for Matthew was the word “field,” which appears in Matt. 13:36, 38 and Matt. 13:44.[3]

There are strong indications, however, that at an earlier stage of the pre-synoptic tradition the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables belonged to a larger literary unit consisting of the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident and the Demands of Discipleship discourse.[4] We have entitled this conjectured narrative-sayings complex “Cost of Entering the Kingdom of Heaven.” A common theme—the value of the Kingdom of Heaven—unites the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident with the twin parables. In the parables, the Kingdom of Heaven, a term that is mentioned 3xx in the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident,[5] is likened to a hidden treasure and a pearl.

An additional link between the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables and the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven is the sale of all the possessions belonging to the protagonists of both parables, which mirrors Jesus’ requirement of the rich man to sell all that he had in order to become his full-time disciple.[6] It was the occurrence of πάντα ὅσα + ἔχειν (“all that” + “to have”) in both the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident (L45) and the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables (L7, L14) that first prompted Lindsey to suggest that the two parables were originally told in response to the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident.[7] The theme of giving up everything one has recurs in the Demands of Discipleship (L18), the second passage that belonged to the conjectured “Cost of Entering the Kingdom of Heaven” complex.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

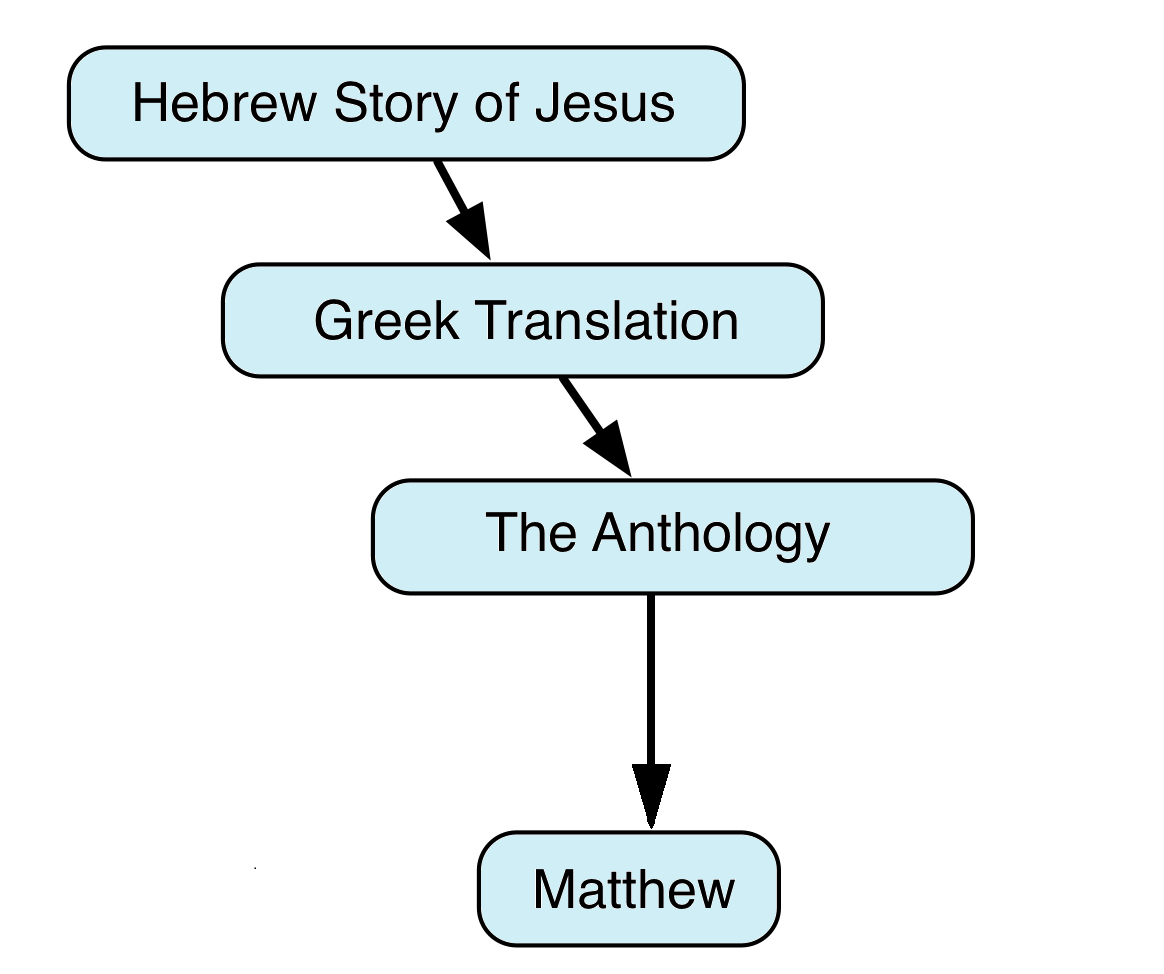

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

The Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables are unique to the Gospel of Matthew. The Hebraic quality of these unique Matthean parables strongly suggests that the author of Matthew copied them from his second source, the Anthology (Anth.). Versions of the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables are also found in the non-canonical Gospel of Thomas.[8] It is unclear whether the Gospel of Thomas is directly dependent on Matthew or whether the author of the Gospel of Thomas learned of these parables from another (perhaps oral?) source. Their secondary nature in comparison with Matthew is recognized by most scholars.[9]

The Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables are unique to the Gospel of Matthew. The Hebraic quality of these unique Matthean parables strongly suggests that the author of Matthew copied them from his second source, the Anthology (Anth.). Versions of the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables are also found in the non-canonical Gospel of Thomas.[8] It is unclear whether the Gospel of Thomas is directly dependent on Matthew or whether the author of the Gospel of Thomas learned of these parables from another (perhaps oral?) source. Their secondary nature in comparison with Matthew is recognized by most scholars.[9]

Crucial Issues

- Were the actions of the man who discovered the hidden treasure unethical?

Comment

Hidden Treasure Parable

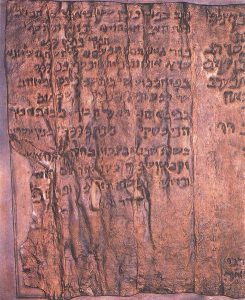

A segment of the Qumran Copper Scroll. The Copper Scroll identifies the purported locations of supposedly hidden treasures. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

L1-8 The discovery of hidden treasure would have been a familiar tale to Jesus’ audience. According to Josephus during the Roman siege of Jerusalem many of its inhabitants had hidden their valuable possessions in the ground in order to keep them from being plundered (J.W. 7:115).[10] Such must have been the practice in other times of war, and the discovery of hidden treasure is mentioned from time to time in ancient Jewish sources[11] as well as by Greek authors.[12] These examples indicate that Jesus’ parable was not rooted in fantasy, but in the images and transactions of real life. Of course, real-life discoveries of hidden treasure captured the imagination and gave rise to folktales, legends and proverbs about such discoveries.[13]

L1 [εἶπεν δὲ πρὸς αὐτοὺς παραβολὴν λέγων] (GR). In Matt. 13 the Hidden Treasure parable lacks any kind of narrative introduction. In its original context the Hidden Treasure parable probably had an introduction similar to the one we have supplied in GR. Compare the narrative introduction to the Lost Sheep parable (Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, L8-9).

[וַיִּמְשׁוֹל לָהֶם מָשָׁל לֵמאֹר] (HR). On reconstructing εἰπεῖν + παραβολή (“to tell a parable”) as מָשַׁל מָשָׁל (“tell a parable”), see Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, Comment to L8-9.

L2 τίνι ὁμοιώσω τὴν βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν (GR). In our examination of the Mustard Seed and Starter Dough parables we discovered that the author of Matthew altered the beginning of these two parables by changing the opening question and answer (“To what will I compare the Kingdom of Heaven? It is like…”) to a simple declaration (“The Kingdom of Heaven is like…”).[14] Since the opening declaration “The Kingdom of Heaven is like…” in the Matthean versions of the Mustard Seed and Starter Dough parables is redactional, it is probable that the opening declaration of the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables is redactional as well. Here in L2 we have reconstructed the kind of question that likely appeared in Anth. at the opening of the Hidden Treasure parable. The author of Matthew subsequently shortened the opening question and answer into the stereotypical declaration with which he opened the majority of parables in his parable discourse (Matt. 13:31, 33, 44, 45, 47).

לְמַה אֲדַמֶּה מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם (HR). For our reconstruction of the question that we believe originally opened this parable, see Mustard Seed and Starter Dough, Comment to L6.

On reconstructing the phrase ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν (hē basileia tōn ouranōn, “the Kingdom of Heaven”) as מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם (malchūt shāmayim, “Kingdom of Heaven”), see Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, Comment to L39.

L3 ὁμοία ἐστὶν (GR). In rabbinic parables we never find a sentence beginning with -דּוֹמֶה לְ (“it is like”) in answer to an opening question. We suspect that the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua added the phrase ὁμοία ἐστίν (“it is like”) because he wished to avoid opening a sentence with a dative. See Mustard Seed and Starter Dough, Comment to L7.

L4 θησαυρῷ κεκρυμμένῳ ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ (Matt. 13:44). The phrase ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ (en tō agrō, lit., “in the field”) is a bit strange, since no particular field has been indicated. The presence of the definite article “the” before “field” may be due to a literal translation from a Hebrew source that read בַּשָּׂדֶה (basādeh, “in the field”) in an indefinite sense.[15] Hebrew often adds the definite article when no immediately identifiable person or thing is intended.[16]

לְמַטְמוֹן בַּשָּׂדֶה (HR). We suspect that behind the phrase θησαυρός κεκρυμμένος (thēsavros kekrūmmenos, “treasure having been hidden”) stood the noun מַטְמוֹן (maṭmōn, “hidden treasure”) in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua. In MT מַטְמוֹן occurs 5xx (Gen. 43:23; Isa. 45:3; Jer. 41:8; Job 3:21; Prov. 2:4), and in all but one case מַטְמוֹן was rendered in LXX as θησαυρός.[17] While θησαυρός is usually an adequate translation of מַטְמוֹן, it does not convey the sense of hiddenness which is inherent in the Hebrew root ט-מ-ן. Since the hiddenness of the treasure is essential to the parable we believe the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua added the participle κεκρυμμένος, whereas there was no corresponding participle in his Hebrew source.[18]

Compare our reconstruction to the following rabbinic parable:

דבר אחר רבי שמעון בן יוחאי אומר משל למה הדבר דומה לאחד שנפלה לו פלטרית במדינת הים בירושה ומכרה בדבר מועט והלך הלוקח ומצא בה מטמוניות ואוצרות של כסף ושל זהב ושל אבנים טובות ומרגליות התחיל המוכר נחנק כך עשו מצרים ששלחו ולא ידעו מה שלחו דכתיב ויאמרו מה זאת עשינו כי שלחנו וגו′.

Another interpretation [of What have we done? (Exod. 14:5)]: Rabbi Shimon ben Yohai[19] says, “A parable. To what may the matter be compared? To one to whom a palace in a province across the sea came as an inheritance and he sold it for a small amount of money. And the purchaser went and found in it hidden treasures [מַטְמוֹנִיּוֹת] and stores of silver and of gold and of precious stones and pearls. [When he heard of this,] the seller began to choke [with regret]. In the same way did the Egyptians behave when they sent [Israel] away without realizing what they had sent, as it is written: And they said: ‘What have we done? For we have sent [the Israelites’ (Exod. 14:5)], etc.” (Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, BeShallaḥ chpt. 2 [ed. Lauterbach, 1:133])[20]

In the parable above, Rabbi Shimon ben Yohai uses the term מַטְמוֹנֶת (maṭmōnet), a synonym of מַטְמוֹן. The following is an example of מַטְמוֹן for “hidden treasure” in a rabbinic source:

ר′ פנחס בן יאיר פתח אם תבקשנה ככסף וכמטמונים תחפשנה. אם אתה מחפש אחד ד″ת כמטמונים הללו אין הקב″ה מקפח שכרך, משל לאדם אם מאבד סלע או בולרין בתוך ביתו הוא מדליק כמה נרות כמה פתילות עד שיעמוד עליהם, והרי דברים קל וחומר ומה אלו שהם חיי שעה של עולם הזה אדם מדליק כמה נרות וכמה פתילות עד שיעמוד עליהם וימצאם, דברי תורה שהם חיי העולם הזה וחיי העה″ב אין אתה צריך לחפש אחריהם כמטמונים הללו, הוי אם תבקשנה ככסף.

Rabbi Pinhas ben Yair opened [his discourse with] If you will seek it like silver and search for it like hidden treasures [Prov. 2:4]: If you search for even one of the words of the Torah as you would for these hidden treasures [כְּמַטְמוֹנִים], be assured that the Holy One, blessed be he, will not hold back your reward. A parable: [It may be compared] to a person if he loses a sela or a bolrin [i.e., various types of coin—DNB and JNT] within his house, he lights a few lamps and a few lanterns until he discovers them. And behold, it is a matter of kal vahomer. If even for things that last only an hour in this world a person lights a few lamps and a few lanterns until he discovers them and finds them, how much more the words of Torah, which last in this world and in the world to come? Do you not need to search after them as you would for hidden treasures [כְּמַטְמוֹנִים]? Hence, If you seek for it like silver [Prov. 2:4], etc. (Song Rab. 1.1.9 [ed. Etelsohn, 18])

As in the parable of Pinhas ben Yair, where the great worth of the Torah is emphasized, in his Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables, Jesus emphasized the great worth of the Kingdom of Heaven, that is, of being his full-time disciple. If Chana Safrai’s suggestion that Torah study and the Kingdom of Heaven were parallel concepts is accepted, then we must conclude that the messages of Jesus’ Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables and the parable of Pinhas ben Yair were very similar indeed.[21]

The noun שָׂדֶה (sādeh, “field”) was almost always translated ἀγρός (agros, “field”) in LXX.[22] Moreover, the LXX translators rarely used ἀγρός to translate a word other than שָׂדֶה.[23] There can be little doubt, therefore, regarding our choice of שָׂדֶה in HR.

L5 ὃν εὑρὼν ἄνθρωπος ἔκρυψεν (Matt. 13:44). Note the placement of the verb ahead of the subject, which might reflect the word order of a Hebrew Ur-text.[24]

שֶׁמָצָא אָדָם (HR). In Choosing the Twelve, Comment to L11, we established that אֲשֶׁר (’asher, “who,” “which”) is a reasonable reconstruction of ὅς (hos, “who,” “which”). Here, however, we have adopted for HR the Late Biblical and Mishnaic equivalent to אֲשֶׁר, namely -שֶׁ (she-, “who,” “which”),[25] because we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in a style resembling Mishnaic Hebrew. Since the relative pronoun -שֶׁ does occur in the Hebrew Scriptures it is easy to establish that the LXX translators regarded ὅς as a suitable equivalent. The LXX translators more often rendered -שֶׁ as ὅς than any other alternative.[26]

In LXX the verb εὑρίσκειν (hevriskein, “to find”) mainly occurs as the translation of מָצָא (mātzā’, “find”).[27] Likewise, although מָצָא was translated a variety of ways in LXX, the most common by far was with εὑρίσκειν.[28]

We have chosen to reconstruct ἄνθρωπος as אָדָם (’ādām, “person”) instead of אִישׁ (’ish, “man”) for two reasons. First, in MH אָדָם became more common than אִישׁ,[29] and we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in a style similar to MH. Second, אָדָם is a more precise equivalent of ἄνθρωπος than אִישׁ, although in LXX ἄνθρωπος was used to render both terms.[30]

וְטָמַן אֹתוֹ (HR). In LXX κρύπτειν is used to translate several Hebrew verbs, טָמַן (ṭāman, “hide”) being prominent among them.[31] We also find that the LXX translators rendered most instances of טָמַן either with κρύπτειν or with compounds of κρύπτειν such as ἐγκρύπτειν or κατακρύπτειν.[32] Other options for reconstructing κρύπτειν include הִסְתִיר (histir, “hide,” “conceal”) and חָבָא (ḥāvā’, “hide”; var.: חָבָה [ḥāvāh]).[33] Having reconstructed θησαυρός κεκρυμμένος (“treasure having been hidden”) as מַטְמוֹן in L4, it makes sense to reconstruct the verb κρύπτειν (krūptein, “to hide”) using the same Hebrew root.

L6 καὶ ἀπὸ τῆς χαρᾶς αὐτοῦ (Matt. 13:44). Supposing Jesus told this parable in response to the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident, we should contrast the rich man’s sorrow with the unbounded joy of the man in the parable. The point of the parable is that just as the man who sold everything to buy the field made a reasonable exchange that brought him great joy, so selling one’s possessions in order to take up a life of itinerating discipleship is a reasonable action that promises great reward.[34]

On reconstructing χαρά (chara, “joy”) with שִׂמְחָה (simḥāh, “joy”), see Return of the Twelve, Comment to L4.

L7-8 ὑπάγει…πωλεῖ…ἔχει…ἀγοράζει (Matt. 13:44). There is an abrupt change from past tense to present tense at this point in the text: “The Kingdom of Heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which a man found and hid, and in his joy goes and sells all that he has and buys that field.” Greek, like English, would tend to use present tense verbs in such a parable, and Lindsey supposed that these present tense forms—ὑπάγει (hūpagei, “he goes”), πωλεῖ (pōlei, “he sells”), ἔχει (echei, “he has”) and ἀγοράζει (agorazei, “he buys”)—are the author of Matthew’s replacements for Hebrew past tense forms (personal communication).

Lindsey’s supposition is supported by the fact that in the Priceless Pearl parable the corresponding verbs—πέπρακεν (pepraken, “he sold”), εἶχεν (eichen, “he had”) and ἠγόρασεν (ēgorasen, “he bought”)—are in the past tense (Matt. 13:46). Additional support is provided by the structurally similar parables of the Mustard Seed (Matt. 13:31-32; Mark 4:30-32; Luke 13:18-19) and Starter Dough (Matt. 13:33; Luke 13:20-21). The verbs of these parables are also past tense.

ἀπῆλθεν καὶ ἐπώλησεν πάντα ὅσα εἶχεν (GR). In addition to changing the tense of the verbs, it seems likely that the author of Matthew switched the verb for “to go” to ὑπάγειν (hūpagein, “to go”), which is characteristic of Matthean vocabulary.[35] We conjecture that in the pre-Synoptic source the verb was ἀπέρχεσθαι (aperchesthai, “to go away”), the same verb used in Matt. 13:45 (L14).

L7 ὑπάγει καὶ πωλεῖ (Matt. 13:44). The construction “to go” + conjunction + verb is an Hebraism.[36] The same structure appears again in L14.

הָלַךְ וּמָכַר (HR). On reconstructing ἀπέρχεσθαι (aperchesthai, “to go away”) with הָלַךְ (hālach, “walk,” “go”), see Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, Comment to L7. On reconstructing πωλεῖν (pōlein, “to sell”) with מָכַר (māchar, “sell”), see Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L46.

πάντα ὅσα ἔχει (GR). Although Codex Vaticanus omits πάντα here, we have included it in GR because the reading is well attested in other NT manuscripts.[37] A phrase almost identical to “all that he has” is found in Luke’s version of Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident (Luke 18:22: πάντα ὅσα ἔχεις, “all that you have”) and in the Demands of Discipleship discourse (Luke 14:33: πᾶσιν τοῖς ἑαυτοῦ ὑπάρχουσιν, “all your possessions”). According to Lindsey’s hypothesis, this connecting link between Luke’s version of the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident (TT), the Demands of Discipleship discourse (DT) and the parables of the Treasure and the Pearl, which are unique to Matthew, is the result of their common dependence on pre-synoptic sources that go back to a conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

כֹּל מַה שֶּׁהָיָה לוֹ (HR). We have reconstructed this phrase in a style similar to MH. Compare our reconstruction with the sentence in the following baraita:

תנו רבנן לעולם ימכור אדם כל מה שיש לו וישא בת תלמיד חכם

Our rabbis taught: “Let a man always sell everything he has and marry the daughter of a scholar.” (b. Pes. 49b)

As in the above example, we have omitted the direct object marker אֶת from HR.[38]

On reconstructing πᾶς (pas, “all,” “every”) with כָּל (kol, “all,” “every”), see Demands of Discipleship, Comment to L32.

L8 καὶ ἀγοράζει τὸν ἀγρὸν ἐκεῖνον (Matt. 13:44). In our idiomatic and dynamic English translations of HR we have translated this phrase as “to buy that field” because we believe καί (“and”) is a translation of -וְ (“and”). The Hebrew conjunction -וְ is often used to indicate purpose; therefore, “and bought that field” can mean “in order to buy that field.” We have translated “and bought it” (Matt. 13:46), the corresponding phrase in the second parable, in the same way (i.e., “to buy it”).

וְלָקַח אֹתָהּ הַשָּׂדֶה (HR). In BH the verb לָקַח (lāqaḥ) means “take,” but in MH לָקַח usually means “purchase” or “buy,”[39] while קָנָה (qānāh), which in BH usually means “buy” came to have “possess” as its primary meaning in MH. Since we have chosen to reconstruct the Hidden Treasure parable in a style resembling MH, we have adopted לָקַח for HR.

Examples of the pairing of לָקַח (“buy”) with מָכַר (“sell”) in Mishnaic Hebrew include the following:

הַמְקַבֵּל עָלָיו לִהְיוֹת נֶאֱמָן מְעַשֵּׂר אֶת שֶׁהוּא אוֹכֵל וְאֶת שֶׁהוּא מוֹכֵר וְאֶת שֶׁהוּא לוֹקֵחַ

The one who undertakes to be trustworthy tithes what he eats and what he sells [מוֹכֵר] and what he buys [לוֹקֵחַ]…. (m. Dem. 2:2)

בְּנֵי הָעִיר שֶׁמָּכְרוּ רִחוֹבָהּ שֶׁלָּעִיר לוֹקְחִים בְּדָמָ<יוֹ> בֵּית הַכְּנֶסֶת בֵּית…סְפָרִים לוֹקְחִים תּוֹרָה אֲבָל אִם מָכְרוּ תוֹרָה לֹא יִקְּחוּ סְפָרִים

The residents of a city that sold [שֶׁמָּכְרוּ] one of the city’s open places may buy [לוֹקְחִים] with its proceeds a synagogue…. [If they sold] scrolls they may buy [לוֹקְחִים] a Torah scroll, but if they sold [מָכְרוּ] a Torah scroll they may not buy [יִקְּחוּ] other scrolls. (m. Meg. 3:1)

נָפְלוּ לָה עֲבָדִים וּשְׁפָחוֹת הַזְּקֵנִים יִמָּכְרוּ וְיִלָּקַח בָּהֶן קַרְקָע…נָפְלוּ לָהּ זֵיתִים וּגְפָנִים הַזְּקֵנִים יִימָּכְרוּ לָעֵצִים וְיִלָּקַח בָּהֶן קַרְקָע

If a woman inherited aging male or female slaves, they should be sold [יִמָּכְרוּ] and land should be bought [וְיִלָּקַח] with the proceeds….if she inherited aging olive trees or vines, they should be sold [יִימָּכְרוּ] for wood and land should be bought [וְיִלָּקַח] with it…. (m. Ket. 8:5)

Had we reconstructed the parable in a biblicizing style we would have reverted τὸν ἀγρὸν ἐκεῖνον (ton agron ekeinon, “that field”) to Hebrew as אֶת הַשָּׂדֶה הַהוּא (’et hasādeh hahū’, “that field”), but since we prefer a Mishnaic style of Hebrew for parables and other direct speech we have adopted אֹתָהּ הַשָּׂדֶה (’ōtāh hasādeh, “that field”).[40]

Priceless Pearl Parable

L9 καὶ πάλιν εἶπεν (GR). Just as we suspect the author of Matthew abbreviated the introduction to the Hidden Treasure parable (see above, Comment to L2), so we suspect that he abbreviated the introduction to the Priceless Pearl parable as well. Between the Mustard Seed and Starter Dough parables (L26) Luke has the phrase καί πάλιν εἶπεν (“and again he said”; Luke 13:20). We believe the author of Luke copied this phrase from Anth. This same phrase may originally have joined the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables, which the author of Matthew trimmed down to πάλιν (palin, “again”).

On reconstructing καί πάλιν εἶπεν as וְעוֹד אָמָר, see Mustard Seed and Starter Dough, Comment to L26.

L10 τίνι ὁμοιώσω τὴν βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν (GR). Above in Comment to L2 we cited our reasons for suspecting that the author of Matthew changed an opening question (“To what will I compare the Kingdom of Heaven? It is like…”) into a declaration (“The Kingdom of Heaven is like…”) in the Hidden Treasure parable. We think it is probable that he did the same with the Priceless Pearl parable. Therefore in GR and HR we have attempted to restore the wording of the sources that stood behind Matthew’s version of the Priceless Pearl parable.

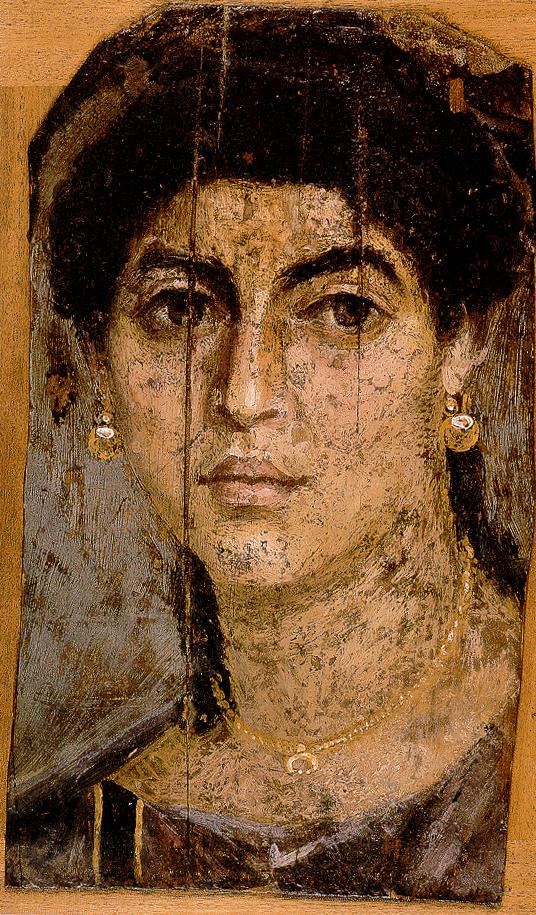

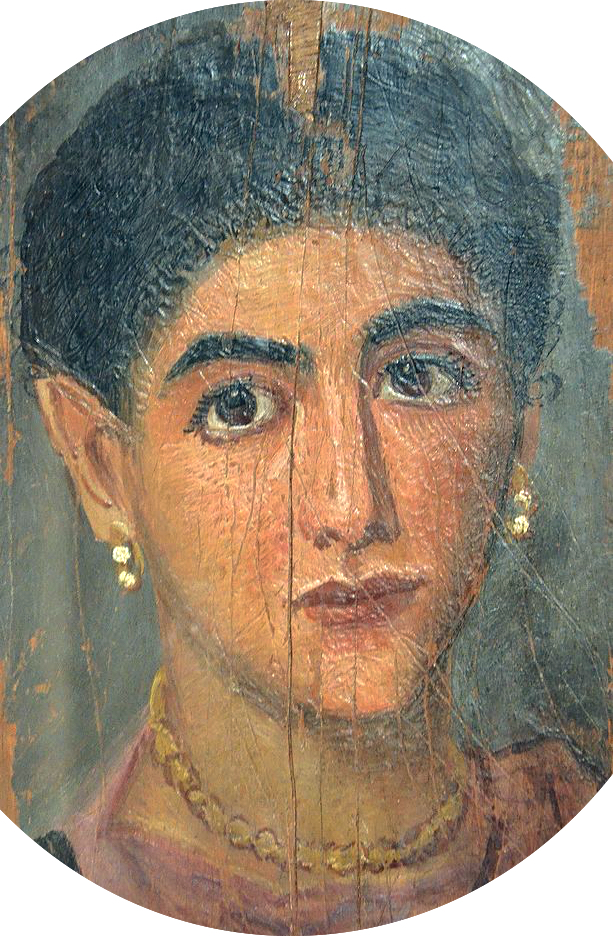

Fayum mummy portrait of a woman with pearl earrings (first cent. C.E.). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

L12 ἀνθρώπῳ ἐμπόρῳ (GR). Although Codex Vaticanus omits ἀνθρώπῳ, we have included it in GR because the reading is well attested.[41] Its authenticity is supported by the Gospel of Thomas, which probably depends on Matthew, and also by its Hebraic quality. As Moule noted, the use of ἄνθρωπος in apposition to a noun is an Hebraism.[42] Examples of this construction in HB include: אִישׁ שַׂר וְשֹׁפֵט (“prince and judge”; Exod. 2:14); אִישׁ כֹּהֵן (“priest”; Lev. 21:9); אִישׁ סָרִיס (“eunuch”; Jer. 38:7); אִשָּׁה אַלְמָנָה (“widow”; 1 Kgs. 7:14).[43]

In the first parable Jesus compared the Kingdom of Heaven to a valuable object: treasure. Therefore, one expects the Kingdom of Heaven to be compared to the “priceless pearl,” the valuable object of the second parable. Instead, the Kingdom is compared to a pearl merchant. If this is the way Jesus told the parable, then apparently there is no significance to this difference between the two parables. The point of comparison between the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables and the rich man’s choice is the beneficial exchange of all one’s property for the sake of gaining something even more valuable.[44] If the parable has been altered by a later editor, perhaps originally the parable was: “The Kingdom of Heaven is like a pearl of rare beauty, which a pearl merchant found and went and sold everything he had to buy it.”

Young noted that, in contrast to the man in the first parable, who might have been an ordinary laborer, the main character in the second parable is a wealthy merchant.[45] In addition, Ze’ev Safrai noted that merchants typically lived in cities,[46] so there is probably a rural versus urban contrast between the two protagonists of the twin parables as well.[47] Perhaps Jesus intended the wealthy merchant to resemble the rich man whose question occasioned this discourse on the worth of the Kingdom of Heaven.

אִישׁ תַּגָּר (HR). In LXX the noun ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos, “person,” “human”) usually occurs as the translation either of אָדָם (’ādām, “person,” “human”) or אִישׁ (’ish, “man,” “adult human male”), with the former slightly in the lead.[48] Similarly, in LOY we more frequently reconstruct ἄνθρωπος with אָדָם than אִישׁ,[49] but occasionally, as here, אִישׁ is preferable for HR.

Matthew 13:45 is the only instance of the noun ἔμπορος (emporos, “merchant”) in the Gospels.[50] In LXX ἔμπορος appears 25xx, where it translates the root ס-ח-ר 10xx (usually in the participial form סֹחֵר)[51] and the root ר-כ-ל 8xx (usually in the participial form רֹכֵל).[52] The noun רוֹכֵל (rōchēl, “peddler”) appears 1x in DSS (11Q20 XII, 12), and in the Mishnah 7xx,[53] but “peddler” does not seem like an apt term for a pearl merchant. The noun סוֹחֵר (sōḥēr, “seller”) occurs 5xx in the Mishnah, but always in the construct state: סוֹחֲרֵי בְהֵמָה (sōḥarē vehēmāh, “sellers of cattle”; m. Shek. 7:2); סוֹחֲרֵי שְׁבִיעִית (sōḥarē shevi‘it, “sellers of seventh-year produce”; m. Rosh Hash. 1:8; m. Sanh. 3:3 [2xx]; m. Shevu. 7:4). We have therefore settled on the noun תַּגָּר (tagār, “traveling merchant”) for HR.[54] In a Hebrew manuscript of Ben Sira from Masada תַּגָּר appears where the LXX version has ἔμπορος (Sir. 42:5), which demonstrates not only that the two terms were equivalent, but also that תַּגָּר was current in the time of Jesus.

Davies and Allison suggested the rabbinic אִמְפּוֹרִין (’impōrin, “merchants”), a loanword from Greek, as a possible reconstruction for ἔμπορος.[55] However, in Jewish sources this word is extremely rare, occurring only in Aramaic in late Targumim, and only in the plural form.[56] For these reasons, אִמְפּוֹרִין appears not to be a viable option for a Hebrew reconstruction.

הַמְּבַקֵּשׁ (HR). Options for reconstructing ζητεῖν (zētein, “to seek”) include חִפֵּשׂ (ḥipēs, “search,” “dig”), בִּקֵּשׁ (biqēsh, “search,” “request”) and דָּרַשׁ (dārash, “search,” “inquire”). In the parable of Rabbi Pinhas ben Yair (quoted above in Comment to L4) חִפֵּשׂ was used for the searching of hidden treasure, but the selection of this verb in Rabbi Pinhas ben Yair’s parable was influenced by the biblical verse it illustrates, and may not be a sure guide in our choice for HR. In MH the meaning “dig” for חִפֵּשׂ predominates,[57] a sense that does not suit the context of the Priceless Pearl parable, and the use of חִפֵּשׂ had become relatively rare.[58] In addition, the LXX never translated חִפֵּשׂ with ζητεῖν.[59] The verb דָּרַשׁ was translated in LXX as ζητεῖν or one of its compounds,[60] but in MH דָּרַשׁ came to be used in the sense of “expound” or “interpret,” which again is not suitable for our context. We have therefore settled upon בִּקֵּשׁ for HR. In LXX ζητεῖν occurs as the translation of בִּקֵּשׁ more than any other verb,[61] and בִּקֵּשׁ was translated by ζητεῖν and its compounds more often than any other Greek verb.[62] Moreover, the collocation of בִּקֵּשׁ with מָצָא (mātzā’, “find”), which is common in Hebrew also serves to confirm our choice for HR.[63]

Fayum mummy portrait of a woman with pearl earrings (ca. 150-200 C.E.). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

καλοὺς μαργαρείτας (Matt. 13:45). Pearls were the most valuable of all gems until the early 19th century when diamonds surpassed them in value.[64] The historian Pliny the Elder (23-79 C.E.) wrote that in his time pearls were first in value among all precious things (Nat. Hist. 9:54). According to Pliny the pearls that came from the Red Sea were especially praised (Nat. Hist. 9:54; cf. 12:1, 41).[65]

If the twin parables originally belonged to the same context as the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident, it is possible that Jesus intentionally mentioned the word “good” in the phrase “good pearls” in order to allude to the rich man’s use of “good” (Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, L8).

מַרְגָּלִיּוֹת טוֹבוֹת (HR). In BH פְּנִינָה (penināh) is sometimes translated as “pearl,” however there are no instances where פְּנִינָה unambiguously refers to pearls and not to some other precious gemstone.[66] In MH the word for pearl is מַרְגָּלִית (margālit).[67] The rabbinic expression מַרְגָּלִיּוֹת טוֹבוֹת (margāliyōt ṭōvōt, “good pearls,” i.e., “pearls of fine quality”), the rabbinic equivalent of καλοὶ μαργαρῖται in Matt. 13:45, appears in Song Rab. 4:5.1; Eccl. Rab. 1:1.1; Seder Eliyahu Rabbah (25) 23.1 (Braude-Kapstein, 278).[68] In LXX the adjective καλός (kalos, “beautiful”) is approximately three times more often the translation of טוֹב (ṭōv, “good”) than of יָפֶה (yāfeh, “beautiful”).[69]

L13 ἕνα πολύτειμον μαργαρείτην (Matt. 13:46). Describing pearls, Pliny the Elder wrote:

Their whole value lies in their brilliance, size, roundness, smoothness and weight, qualities of such rarity that no two pearls are found that are exactly alike. (Nat. Hist. 9:56)[70]

מַרְגָּלִית אַחַת יְקָרָה (HR). In the Hebrew language there are no degrees of comparison of the adjective. There is no way to distinguish between the positive, comparative and superlative forms of the adjective. Therefore, πολύτειμον (polūteimon, “very valuable”) probably is just a dynamic translation of יְקָרָה (yekārāh), which could be translated “valuable,” “more valuable” and “the most valuable.” In this context, we must assume that the adjective יְקָרָה is the superlative, and means “the most valuable,” that is, “a priceless pearl.”[71] The phrase מרגלית אחת appears in Pesik. Rab. 1:32 and Tanḥ. on Deut. 29:9 (Nitzavim 4).[72]

L14 ἀπῆλθεν καὶ ἐπώλησεν πάντα ὅσα εἶχεν (GR). We suspect that the author of Matthew attempted to polish the Greek of his source by changing the aorist ἀπῆλθεν (apēlthen, “he went”; cf. GR L7) to the participle ἀπελθὼν (apelthōn, “going”), and exchanging the aorist ἐπώλησεν (epōlēsen, “he sold”; cf. GR L7) for πέπρακεν, a perfect form of πιπράσκειν (pipraskein, “to sell”). These editorial changes do not affect the meaning, but do improve the Greek style of the parable.

On the Hebraic structure “to go” + verb, see above, Comment to L7.

The phrase πάντα ὅσα εἶχεν (pana hosa eichen, “all that he had”) links the Priceless Pearl parable to the Hidden Treasure parable (see above, Comment to L7). In both parables the actor sells all he has in order to obtain a priceless possession. The action in the parables parallels Jesus’ instruction to the rich man to sell all he owns in order to enter the Kingdom of Heaven, that is, in order to become a disciple, whereby he will obtain a reward greater than all the riches he possessed.

הָלַךְ וְמָכַר כֹּל מַה שֶּׁהָיָה לוֹ (HR). Our reconstruction is identical to that in L7.

L15 וְלָקַח אוֹתָהּ (HR). On reconstructing ἀγοράζειν with לָקַח, see above, Comment to L8.

Redaction Analysis[73]

| Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl Parables | |||

| Matthew | Anthology | ||

| Total Words: |

54 | Total Words: |

63 [69] |

| Total Words Identical to Anth.: |

46 | Total Words Taken Over in Matt.: |

46 |

| % Identical to Anth.: |

85.19 | % of Anth. in Matt.: |

73.02 [66.67] |

| Click here for details. | |||

The most conspicuous changes the author of Matthew likely made to the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables were his omission of the narrative introductions (L1, L9) and his transformation of the opening questions and answers into declarative statements (L3, L11).[74] By abbreviating the openings of these parables the author of Matthew was more easily able to integrate them into his major parables discourse (Matt. 13:1-53). Within the body of the parables, we suspect that the author of Matthew changed aorist tense verbs into the present tense in L7 and L8 and into a participle in L14. We also believe that the author of Matthew replaced the verb ἀπέρχεσθαι in his source at L7 with his preferred ὑπάγειν. Likewise, the author of Matthew probably inserted πιπράσκειν in L14 where πωλεῖν appeared in his source. The author of Matthew’s use of synonyms appears to be due to a Greek aversion to verbatim repetition. We observe similar substitutions in the Lost Sheep and Lost Coin similes.[75] By comparing the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables to one another and to similar parables such as Mustard Seed and Starter Dough, it has been possible to reconstruct the wording as it likely appeared in Anth.

Results of this Research

1. Were the actions of the man who discovered the hidden treasure unethical? Readers and commentators are often troubled by the ethical implications of Jesus’ Hidden Treasure parable. Did the man who found the treasure and then re-hid it and bought the field for less than the treasure was worth cheat the original owner of the field? Sometimes scholars cite passages from rabbinic literature (e.g., m. Bab. Bat. 4:8-9) to argue that the man’s behavior either was or was not ethical. However, if our contention is correct that Jesus told the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables in response to the rich man who declined his invitation, it becomes clear that the purpose of the parable is not to give ethical instruction, but to illustrate the rich man’s dilemma.[76] Was Jesus’ costly invitation worth it or not? Jesus compared the costly requirements of joining his band of disciples and the rewarding experience of itinerating with him to the situations of a man who sells everything in order to obtain a hidden treasure and a merchant who sells everything to procure a priceless pearl. Had the men in the parables made an exchange to their benefit or to their detriment? Clearly the two men in the parables received more than what it cost them. In the same way, choosing to join Jesus’ itinerating band of disciples would cost the rich man everything he had, but Jesus encouraged the man to trust that the exchange was a bargain. Belonging to Jesus’ band of disciples meant participating in God’s rescue mission to redeem Israel, humankind, and the whole of God’s creation.

Conclusion

Having told the rich man that he must sell all he has in order to enter the Kingdom of Heaven (in other words, to join Jesus’ itinerating band of disciples), Jesus went on to tell two parables in which a person sells everything he owns in order to obtain an object of great worth. Supposing that these twin parables once belonged to the same narrative-sayings complex as the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident enables us to understand their message. Jesus’ demand that the rich man sell everything was not an onerous or unreasonable request; to the contrary, it was a great bargain for the man.[77] Just as the day laborer and the merchant in the parables sold all they had joyfully, knowing that they were making an exchange that would bring them great profit, so too, Jesus’ invitation to the rich man was a golden opportunity. Discipleship was both costly and rewarding.[78] The parables of the Hidden Treasure and the Priceless Pearl were meant to illustrate that point, and readers need not be troubled by the ethical implications of Jesus’ hypothetical scenarios.

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link:

- [1] For abbreviations and bibliographical references, see “Introduction to ‘The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction.’” ↩

- [2] This translation is a dynamic rendition of our reconstruction of the conjectured Hebrew source that stands behind the Greek of the Synoptic Gospels. It is not a translation of the Greek text of a canonical source. ↩

- [3] See Nolland, Matt., 563. ↩

- [4] Lindsey observed that double parables usually concluded Jesus’ fully-developed teaching discourses. See Robert L. Lindsey, “Jesus’ Twin Parables.” Cf. Witherington, 272. ↩

- [5] In the Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven incident the Kingdom of Heaven is mentioned in L64-65, L81 and L117. ↩

- [6] The buying in the two parables is somewhat reminiscent of the rabbinic expression קָנָה חַיֵּי הָעוֹלָם הַבָּא (“obtain the life of the world to come”; m. Avot 2:7; cf. Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Amalek chpt. 4 [ed. Lauterbach, 2:288]; Derech Eretz Zuta 4:3 [ed. Higger, 99-100, lines 11-12]) which is similar to “inherit eternal life,” found in Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, L10. ↩

- [7] See LHNS, 76 §101. ↩

- [8] The versions of the Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl parables in the Gospel of Thomas are as follows:

Jesus said: The Kingdom is like a man who had a treasure [hidden] in his field, without knowing it. And [after] he died, he left it to his [son. The] son did not know (about it), he accepted that field, he sold [it]. And he who bought it, he went, while he was plowing [he found] the treasure. He began to lend money to whomever he wished. (Gos. Thom. §109 [ed. Guillaumont, 55])

Jesus said: The Kingdom of the Father is like a man, a merchant, who possessed merchandise (and) found a pearl. That merchant was prudent. He sold the merchandise, he bought the one pearl for himself. (Gos. Thom. §76 [ed. Guillaumont, 41-42])

- [9] Cf. Davies-Allison, 2:437, 439-440. According to Vermes (Authentic, 142), “The treatment of the hidden treasure in the Gospel of Thomas illustrates the general unreliability of this document as a source of the sayings of Jesus. The perfectly clear and deeply meaningful Gospel parable is completely distorted and the final outcome of the accidental find is that the discoverer becomes a greedy moneylender, an occupation forbidden by the Mosaic Law.” For a different view, see Charles W. Hedrick, Parables As Poetic Fictions: The Creative Voice of Jesus (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1994), 117-141. ↩

- [10] See Jeremias, Parables, 198; Young, JHJP, 213. ↩

- [11] The Mishnah discusses the possibility of finding objects hidden within ancient walls (m. Bab. Metz. 2:4). According to the Tosefta such hidden treasures were attributed to the Amorites, who inhabited the land before the Israelites came (t. Bab. Metz. 2:12. On the hidden treasures of the Amorites, see Eyal Ben-Eliyahu, “The Rabbinic Perception of the Presence of the Canaanites in the Land of Israel,” in The Gift of the Land and the Fate of the Canaanites in Jewish Thought (ed. Katell Berhelot, Joseph E. David and Marc Hirshman; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 275-284, esp. 277. The Jerusalem Talmud tells the story of a rich man in Antioch who was very liberal in giving, but who lost his wealth. Later, while plowing his field, he discovered a treasure that surpassed the value of the wealth he had lost (y. Hor. 3:4 [17a]; cf. Lev. Rab. 5:4; Deut. Rab. 4:8). ↩

- [12] Cf., e.g., Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tayana 2:39. Nolland (Matt., 563-564 n. 123) notes further examples. ↩

- [13] Cf., e.g., Sir. 20:30-31; Philo, Deus §91. ↩

- [14] See Mustard Seed and Starter Dough, Comments to L1-2 and L25-26. ↩

- [15] See Moule, Idiom, 177. Cf. Davies-Allison, 2:346. ↩

- [16] Cf. Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L77. ↩

- [17] The one exception is in Isa. 43:3 where מַטְמוֹן is used in parallel with אוֹצָר (’ōtzār, “treasure,” “treasury”). Since the LXX translators usually rendered אוֹצָר as θησαυρός (See Dos Santos, 5; cf., Hatch-Redpath, 1:651-652) they rendered מַטְמוֹן using a different word in Isa. 43:3. ↩

- [18] It is also possible that κεκρυμμένος was added by the author of Matthew, but since the original hiddenness of the treasure is key to the understanding of the parable and since the repetition of κρύπτειν in L2 seems somewhat inelegant in Greek we believe that the author of Matthew found κεκρυμμένος in his source. ↩

- [19] Rabbi Shimon ben Yohai lived in the mid-second cent. C.E. ↩

- [20] An important difference between the rabbinic parable and Jesus’ parable is that whereas Jesus’ parable interprets a situation (i.e., Jesus’ invitation to join his band of disciples), the rabbinic parable interprets a passage of Scripture. On Rabbi Shimon ben Yohai’s parable, see Young, JHJP, 215-219; Notley-Safrai, 94-95. ↩

- [21] On the parallels between the rabbinic conception of Torah study and Jesus’ understanding of the Kingdom of Heaven, see Chana Safrai, “The Kingdom of Heaven and the Study of Torah” (JS1, 169-198). ↩

- [22] See Dos Santos, 198. ↩

- [23] See Hatch-Redpath, 1:17-18. ↩

- [24] We are indebted to Robert Lindsey for this observation (personal communication). ↩

- [25] See Segal, 42 §77. ↩

- [26] The LXX translators rendered -שֶׁ as ὅς in Judg. 5:7; 2 Esd. 8:20; Ps. 121:3; 122:2; 123:6; 128:6, 7; 134:8, 10; 136:8 (2xx), 9; 143:15 (2xx); 145:3, 5; Song 1:7, 12; 2:7, 17; 3:1, 2, 3, 4 (3xx), 5, 11; 4:1, 2 (2xx), 6: 6:5, 6 (2xx); 8:8; Eccl. 1:3, 7; 2:11, 12, 18, 19 (2xx), 20, 21 (2xx), 22, 24; 3:13, 22; 5:15, 17; 6:3, 7, 24; 10:5, 16, 17; 11:3; 12:3; Jonah 4:10; Lam. 2:15, 16. By way of comparison, the LXX translators rendered -שֶׁ as ὅτι, their second most frequent translation of -שֶׁ, in Jud. 5:7; 6:17; Ps. 123:1, 2, 135:23; Song 1:6 (2xx); 5:2, 8, 9; 6:5; Eccl. 1:17; 2:13, 14, 15, 18: 3:18; 7:10; 8:14 (2xx); 9:5; 12:9; Lam. 5:8. ↩

- [27] See Hatch-Redpath, 1:576-579. ↩

- [28] See Dos Santos, 118. ↩

- [29] See Bendavid, 337. ↩

- [30] See Hatch-Redpath, 1:96-102. ↩

- [31] In LXX κρύπτειν occurs as the translation of טָמַן in Exod. 2:12; Josh. 2:6; 7:22 (Alexandrinus); Ps. 9:16; 30:5; 34:7, 8; 63:6; 139:6; 141:4; Prov. 26:15; Job 18:10; 40:13. ↩

- [32] See Dos Santos, 74. ↩

- [33] Note the phrase וַיִּסָּתֵר דָּוִד בַּשָּׂדֶה (“and David hid himself in the field”; 1 Sam. 20:24), translated καὶ κρύπτεται Δαυιδ ἐν ἀγρῷ in LXX, and the phrase וַיֵּצְאוּ מִן הַמַּחֲנֶה לְהֵחָבֵה בַהשָּׂדֶה (“and they went out from the camp to hide themselves in the field”; 2 Kgs. 7:12), translated καὶ ἐξῆλθαν ἐκ τῆς παρεμβολῆς καὶ ἐκρύβησαν ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ in LXX. ↩

- [34] Cf. Beare, Earliest, 118 §118; Schweizer, 312. ↩

- [35] The verb ὑπάγειν occurs 19xx in Matt., 16xx in Mark, and 5xx in Luke. Matthew copied ὑπάγειν from Mark 6xx (Matt. 8:4 [= Mark 1:44, against Luke 5:14]; 9:6 [= Mark 2:11, against Luke 5:24]; 16:33 [= Mark 8:33]; 19:21 [= Mark 10:21, against Luke 18:22]; 26:18 [= Mark 14:3, against Luke 22:10], 24 [= Mark 14:21, against Luke 22:22]) and ὑπάγειν is found 11xx in verses unique to Matthew (Matt. 5:24, 41; 8:13; 13:44; 18:15; 20:4, 7, 14; 21:28; 27:65; 28:10). ↩

- [36] Examples of the “to go” + and + verb construction can be found in Gen. 35:22; Deut. 31:1; Josh. 5:13; Judg. 1:16; 3:13; 15:4; 2 Sam. 6:12; 11:22; 21:12; 1 Kgs. 2:40; 9:6; 17:5. See Hedrick, Parables As Poetic Fictions, 138. ↩

- [37] Cf. Metzger, 34. ↩

- [38] Cf. Blessedness of the Twelve, Comment to L6. ↩

- [39] See Kutscher, 83 §123, 134 §227; Moshe Bar-Asher, “Mishnaic Hebrew: An Introductory Survey,” in The Literature of the Sages (ed. Shmuel Safrai, Zeev Safrai, Joshua Schwartz, and Peter J. Tomson; CRINT II.3b; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2006), 567-595, esp. 580. ↩

- [40] On this grammatical shift, see Chanan Ariel, “The Shift from the Biblical Hebrew Far Demonstrative ההוא to the Mishnaic Hebrew אותו,” in New Perspectives in Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew (ed. Aaron D. Hornkohl and Geoffrey Khan; University of Cambridge and Open Book Publishers, 2021), 167-195. The phrase אֹתָהּ הַשָּׂדֶה occurs in m. Dem. 6:1; m. Bab. Kam. 6:2; m. Tohar. 6:5, and elsewhere in rabbinic literature. ↩

- [41] On our reasons for basing our reconstruction and commentary on the text of Vaticanus, see “Introduction to ‘The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction,’” under the subheading “Codex Vaticanus or an Eclectic Text?” ↩

- [42] See Moule, Birth, 218. According to Moule, this particular Hebraism “…though peculiar to Matt., yet invariably [occurs—DNB and JNT] in parables (ἐχθρὸς ἄνθρωπος, xiii. 28, ἄνθρωπος ἔμπορος, xiii. 45 (v. l.); ἄνθρωπος οἰκοδεσπότης, xiii. 52, xx. 1, xxi. 33, ἄνθρωπος βασιλεύς, xviii. 23, xxii. 2); and the likelihood, therefore, is that the idiom came by tradition with the parable.” In Lindsey’s terminology, we would say that Matthew copied this Hebraism from Anth. ↩

- [43] See Joüon-Muraoka, 2:478 (§131b) for further examples. Joüon-Muraoka note that this type of construction also exists in Greek, citing ἄνθρωπος ὁδίτης (“wayfarer”; Homer, Iliad 16:263) as an example. ↩

- [44] On the other hand, Flusser suggested on the basis of a similar parable in Mechilta de-Shimon bar Yohai 19:5 that this parable is about God’s love for Israel (Notley-Safrai, 132). According to Flusser’s interpretation, God is the one who prizes Israel above all other things. ↩

- [45] See Young, Parables, 215. ↩

- [46] See Ze’ev Safrai, The Economy of Roman Palestine (London: Routledge, 1994), 228. Safrai also noted that according to rabbinic opinion pearls ought to be sold in cities, but unfortunately he did not cite a source for this opinion. See Ze’ev Safrai, “Urbanization and Industry in Mishnaic Galilee,” in Galilee in the Late Second Temple and Mishnaic Periods (ed. David A. Fiensy and James Riley Strange; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2014), 272-296. ↩

- [47] On contrasting social standings of their respective main characters as a chief characteristic of twin parables, see David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “LOY Excursus: Criteria for Identifying Separated Twin Parables and Similes in the Synoptic Gospels.” ↩

- [48] See Hatch-Redpath, 1:96-102.[79] We also find that the LXX translators generally rendered אִישׁ either as ἀνήρ (’anēr, “man,” “adult human male”) or ἄνθρωπος, the former nearly twice as often as the latter.[80] See Dos Santos, 9. ↩

- [49] See the LOY Excursus: Greek-Hebrew Equivalents in the LOY Reconstructions, under the entry for “ἄνθρωπος.” ↩

- [50] Elsewhere in NT ἔμπορος appears only in Revelation (18:3, 11, 15, 23). Pearls are among the commodities sold by the merchants described in Rev. 18. ↩

- [51] Gen. 23:16; 37:28; 1 Kgs. 10:28; Isa. 23:8; Ezek. 27:12, 18, 21, 36; 38:13; 2 Chr. 1:16. ↩

- [52] 1 Kgs. 10:15; Ezek. 27:15, 17, 20, 22 (2xx), 23 (2xx). ↩

- [53] In the Mishnah רוֹכֵל is found in m. Maas. 2:3; m. Shab. 9:7; m. Bab. Bat. 9:7 (2xx); m. Kel. 2:4; 12:2 (2xx). ↩

- [54] On the term תַּגָּר, see Joseph Klausner, “The Economy of Judea in the Period of the Second Temple,” in The World History of the Jewish People: The Herodian Period (ed. Michael Avi-Yonah; New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1975), 179-205, 361–365, esp. 196, 363 n. 123; Safrai, Economy of Roman Palestine, 228. In MH תַּגָּר came to replace סוֹחֵר (see Bendavid, 356). Examples of תַּגָּר in the Mishnah are found in m. Bab. Metz. 4:3 (4xx); 4:11 (2xx); m. Bab. Bat. 6:6 (2xx); m. Ukz. 2:1. ↩

- [55] See Davies-Allison, 2:438. ↩

- [56] See Jastrow, 78. ↩

- [57] See Jastrow, 493. ↩

- [58] In the Mishnah, for instance, חִפֵּשׂ occurs only once (m. Pes. 2:3). ↩

- [59] See Dos Santos, 68; Hatch-Redpath, 1:597-598. ↩

- [60] See Dos Santos, 45. ↩

- [61] See Hatch-Redpath, 1:597-598. ↩

- [62] See Dos Santos, 30. ↩

- [63] On the pairing of בִּקֵּשׁ with מָצָא, see Friend in Need, Comment to L24. ↩

- [64] See Fred Ward, “The Pearl,” National Geographic 168.2 (Aug. 1985): 193-223, esp. 209. On pearls in the ancient world, see F. S. Bodenheimer, Animal and Man in Bible Lands (Leiden: Brill, 1960), 84-85, 135. ↩

- [65] See H. B. Tristram, Natural History of the Bible (7th ed.; London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1883), 299. ↩

- [66] Even-shoshan (1071) defined the biblical פְּנִינָה as “coral,” but notes that another opinion is “pearl.” Cf. BDB, 819. The singular form פְּנִינָה appears 3xx in MT, always as the name of Elkanah’s wife (1 Sam. 1:2, 4). The plural פְּנִינִים appears 6xx in MT (Job 28:18; Prov. 3:15; 8:11; 20:15; 31:10; Lam. 4:7). JPS usually translates פְּנִינִים as “rubies” (Job 28:18; Prov. 3:15; 8:11; 31:10), but also “jewels” (Prov. 20:15) and “coral” (Lam. 4:7). LXX rendered פְּנִינִים 3xx as λίθοι πολυτελεῖς (“precious stones”; Prov. 3:15; 8:11; 31:10); cf. Jos., Ant. 8:167; 12:40. ↩

- [67] See Bendavid, 271-272. The noun מַרְגָּלִית appears 5xx in Mishnah: m. Bab. Metz. 4:9; m. Arak. 6:5; m. Kel. 11:8; 17:16; 26:2 (cf. m. Avot 6:9 in the appendix added to printed editions of tractate Avot). In m. Kel. 11:8 we find the phrase וַחֲלָיוֹת שֶׁלַּאֲבָנִים טוֹבוֹת וְשֶׁלְּמַרְגָּלִיּוֹת, “beads of precious stones and pearls” (Danby). ↩

- [68] Cf. מרגלית טובה in t. Kid. 5:14[17]; Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version A, chpt. 18 [ed. Schechter, 67]; Gen. Rab. 7:6; Song Rab. 1:1.8; b. Hag. 3a; b. Bab. Bat. 123b. ↩

- [69] See Hatch-Redpath, 1:715-716. ↩

- [70] The discovery of a valuable pearl is also related in a first-century C.E. collection of Aesop’s Fables:

A cockerel on a dunghill, while looking for something to eat, found a pearl. “What a fine thing you are,” said he, “to be lying in so improper a place! If only someone who coveted your value had seen this sight you would long ago have been restored to your original splendour. But my finding you—since I’m much more interested in food than in pearls—is of no possible use either to you or to me.” (Aesopic Fables of Phaedrus 3:12; Loeb)

This fable ironically illustrates the great value placed on pearls in the Greco-Roman world of the first century C.E. ↩

- [71] Since יְקָרָה can mean “the most valuable,” in reconstructing the Hebrew one need not add the adverb מְאֹד (me’od, “very”) to the adjective יְקָרָה, as would modern Hebrew speakers. ↩

- [72] Cf. the variant reading in Gen. Rab. 11:4: אבן אחת טובה של מרגלית. The phrase אבן אחת טובה also appears in Deut. Rab. 1:15 and 3:3. ↩

- [73]

Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl Parables Matthew’s Version Anthology’s Wording (Reconstructed) ὁμοία ἐστὶν ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν θησαυρῷ κεκρυμμένῳ ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ ὃν εὑρὼν ἄνθρωπος ἔκρυψεν καὶ ἀπὸ τῆς χαρᾶς αὐτοῦ ὑπάγει καὶ πωλεῖ ὅσα ἔχει καὶ ἀγοράζει τὸν ἀγρὸν ἐκεῖνον πάλιν ὁμοία ἐστὶν ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν ἀνθρώπῳ ἐμπόρῳ ζητοῦντι καλοὺς μαργαρείτας εὑρὼν δὲ ἕνα πολύτειμον μαργαρείτην ἀπελθὼν πέπρακεν πάντα ὅσα εἶχεν καὶ ἠγόρασεν αὐτόν [εἶπεν δὲ πρὸς αὐτοὺς παραβολὴν λέγων] τίνι ὁμοιώσω τὴν βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν ὁμοία ἐστὶν θησαυρῷ κεκρυμμένῳ ἐν τῷ ἀγρῷ ὃν εὑρὼν ἄνθρωπος ἔκρυψεν καὶ ἀπὸ τῆς χαρᾶς αὐτοῦ ἀπῆλθεν καὶ ἐπώλησεν πάντα ὅσα εἶχεν καὶ ἠγόρασεν τὸν ἀγρὸν ἐκεῖνον καὶ πάλιν εἶπεν τίνι ὁμοιώσω τὴν βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν ὁμοία ἐστὶν ἀνθρώπῳ ἐμπόρῳ ζητοῦντι καλοὺς μαργαρείτας εὑρὼν δὲ ἕνα πολύτειμον μαργαρείτην ἀπῆλθεν καὶ ἐπώλησεν πάντα ὅσα εἶχεν καὶ ἠγόρασεν αὐτόν Total Words: 54 Total Words: 63 [69] Total Words Identical to Anth.: 46 Total Words Taken Over in Matt: 46 Percentage Identical to Anth.: 85.19% Percentage of Anth. Represented in Matt.: 73.02 [66.67]% ↩

- [74] Perhaps the extent of Matthean redaction in Hidden Treasure and Priceless Pearl explains why Martin (Syntax 1, 115 no. 27) did not find these parables to be more Semitic. ↩

- [75] See Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, under the subheading “Redaction Analysis.” ↩

- [76] Jesus often told parables in which the actors made dubious ethical decisions. The point of the parables is not to emulate the unethical behavior, but to make a comparison between two situations. On this issue, see David Flusser, “Parables of Ill Repute.” For a discussion of the ethical dimensions of the man’s decision to hide the treasure and buy the field without disclosing his discovery, see Snodgrass, 243-244. ↩

- [77] Cf. Davies-Allison, 2:437. ↩

- [78] Cf. Donald Hagner, “Matthew’s Parables of the Kingdom [Matthew 13:1-52],” in The Challenge of Jesus’ Parables (ed. Richard N. Longenecker; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000), 117. ↩