Updated: 11 December 2024[1]

Unlike most other biblical commentaries, The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction is not a commentary on any one text, but rather a commentary on the development of the traditions that came to be included in the Synoptic Gospels. The primary concern of this commentary is to better understand Jesus’ actions and words by attempting to get as close as possible to the earliest stages of development of the traditions that are now known only through the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. Thus, a recurring theme in this commentary will be the question of the interrelationship of the Synoptic Gospels, and how this relationship bears on the development of traditions the Synoptic Gospels preserve.

____

The Interrelationship of the Synoptic Gospels

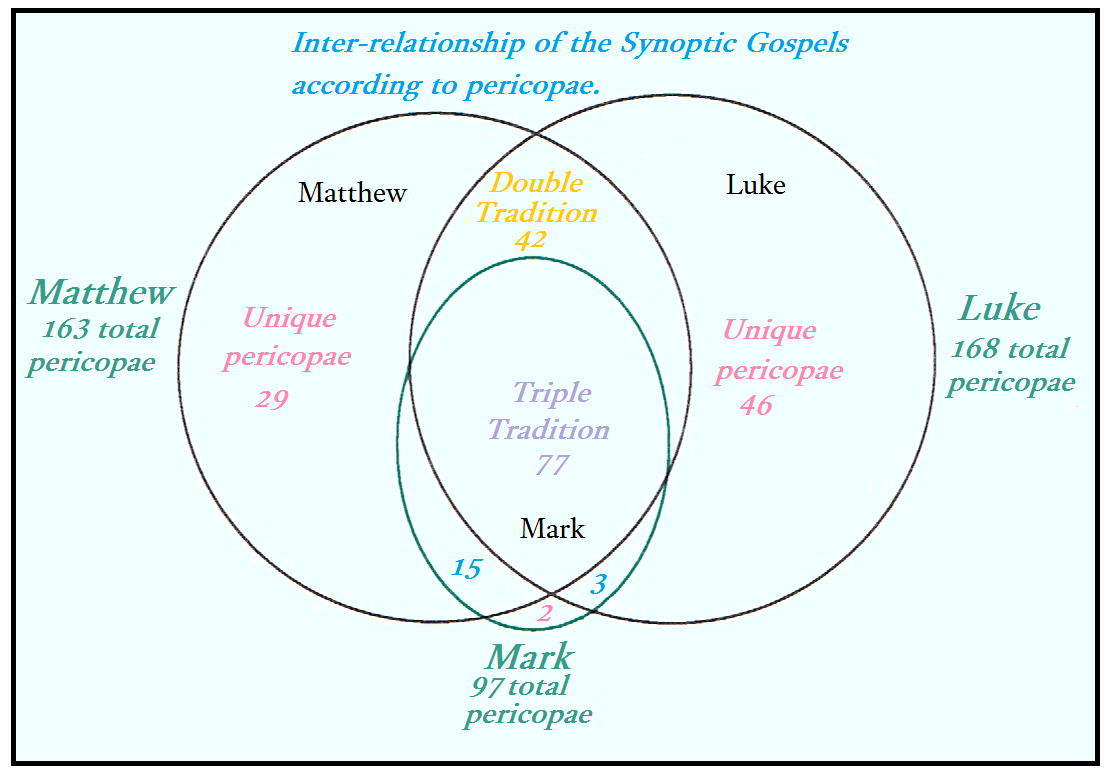

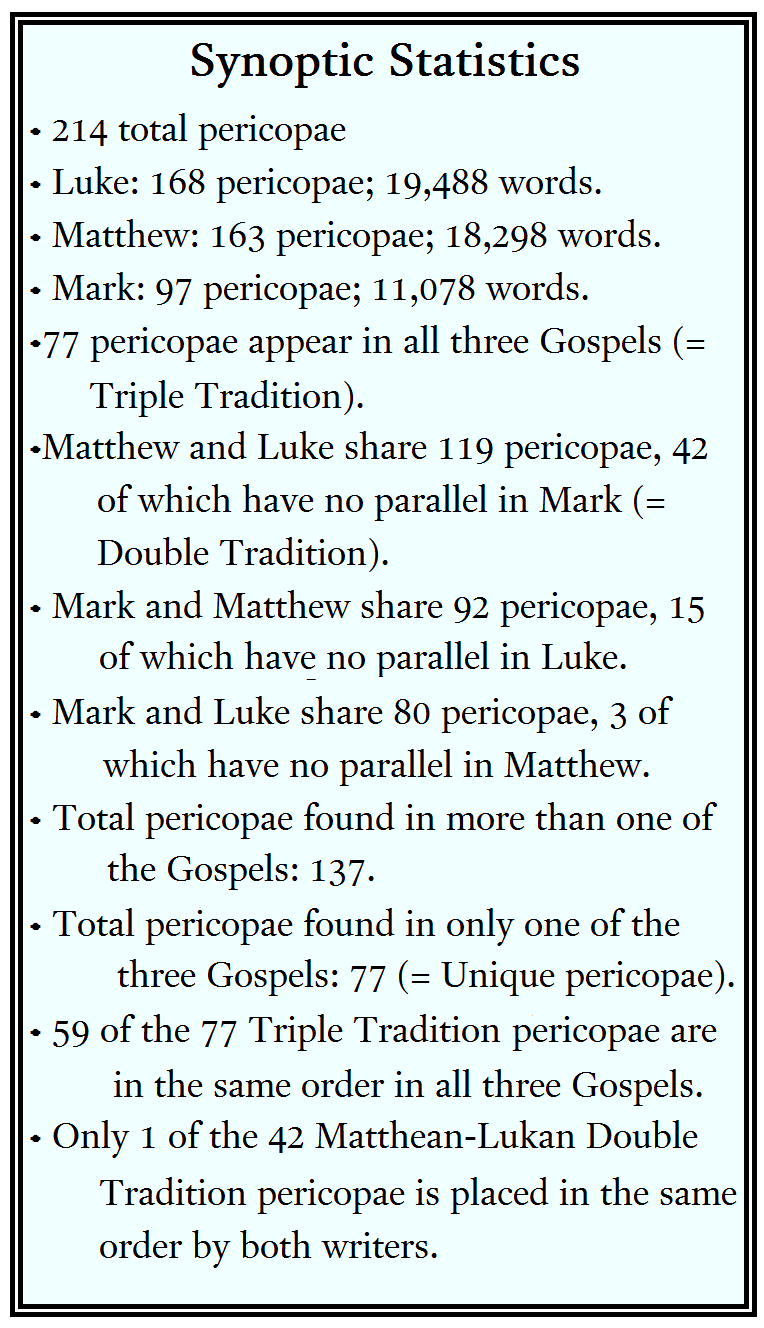

The first three canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke)[2] are referred to as “synoptic” because they share many story units (pericopae; singular: pericope) with identical, or near identical, vocabulary and word order such that they can be arranged in parallel columns in a book called a synopsis. A significant portion of the synoptic pericopae are shared by all three Synoptic Gospels, hence the Matthew-Mark-Luke pericopae are referred to as the Triple Tradition. Another significant portion of the synoptic pericopae appear only in Matthew and Luke; these are referred to as the Double Tradition. Each of the Synoptic Gospels also has unique pericopae not found in the other two Gospels.

Solely on the basis of triply-, doubly- and singly-attested pericopae in the Synoptic Gospels, it is not possible to determine the nature of the interrelationship of Matthew, Mark and Luke, or indeed whether they are interrelated at all. The simplest solution would be that all three Synoptic Gospels drew on a single source that contained all the synoptic pericopae, and that each synoptic writer selected the pericopae he wanted to include in his Gospel without any awareness that two other writers were doing the same. The fact that some pericopae appear in all three Synoptic Gospels, that others appear only in two, and that some appear only in one, could then be attributed (depending on one’s outlook) either to providence or to chance. Additional information, however, rules out this solution.

Solely on the basis of triply-, doubly- and singly-attested pericopae in the Synoptic Gospels, it is not possible to determine the nature of the interrelationship of Matthew, Mark and Luke, or indeed whether they are interrelated at all. The simplest solution would be that all three Synoptic Gospels drew on a single source that contained all the synoptic pericopae, and that each synoptic writer selected the pericopae he wanted to include in his Gospel without any awareness that two other writers were doing the same. The fact that some pericopae appear in all three Synoptic Gospels, that others appear only in two, and that some appear only in one, could then be attributed (depending on one’s outlook) either to providence or to chance. Additional information, however, rules out this solution.

An important fact for understanding the relationship of the Synoptic Gospels is that Matthew, Mark and Luke agree to place 59 of the 77 Triple Tradition pericopae in the same order, but Matthew and Luke agree only once with respect to the placement of the Double Tradition pericopae. Thus the Triple Tradition pericopae share qualities that are not limited to mere selection: the Triple Tradition shares a rough narrative outline as well. These facts prove that some kind of interrelationship between Matthew, Mark and Luke does exist.

The Synoptic Problem deals with the nature of this interrelationship and struggles with such questions as: Which Synoptic Gospel was earliest? Did the earliest Synoptic Gospel influence the other two directly, or was the third Synoptic Gospel influenced by the first only indirectly by means of the second? Were there other sources known to the synoptic writers, some they may have known independently from the other synoptic writers, and some they may have shared?

The prevailing solution to the Synoptic Problem is the theory of Markan Priority: Mark is believed to be the earliest Gospel, and his Gospel was used independently by the authors of Matthew and Luke. Matthew and Luke’s conjectured dependence on Mark explains why there is material shared by all three Gospels. Markan priorists account for the Double Tradition by postulating a separate sayings source (usually referred to as Q), which was known to Matthew and Luke. The solution to the Synoptic Problem adopted by Markan priorists is, therefore, sometimes called the Two-source Hypothesis. Markan Priority offers one solution that can explain how all three Gospels came to share a rough narrative outline: Matthew and Luke are based on Mark, but they independently inserted their Q passages into Mark’s story outline.

The Two-source Hypothesis has several points in its favor. It accounts for the literary sources of the Triple Tradition (Mark) and Double Tradition (Q), and explains how the Triple Tradition passages came to roughly share a common order, whereas there is almost no agreement between Matthew and Luke for the placement of the Double Tradition passages. However, there are certain facts that the theory of Markan Priority cannot explain. One of these is the existence of the pervasive minor agreements of Matthew and Luke against Mark in Triple Tradition contexts. These agreements often consist of words or phrases, or the common omission of words or phrases, hence their designation as minor.[3] The pervasiveness of the minor agreements, however, is of major consequence.[4] They strongly suggest that the authors of Matthew and Luke knew a text other than (or in addition to) Mark as their source for the Triple Tradition.[5]

Another weakness of the theory of Markan Priority came to the attention of Robert L. Lindsey when he undertook a project to translate the Gospel of Mark into modern Hebrew.[6] Lindsey observed that the text of Mark was often much more difficult to translate into Hebrew than were the parallel texts of Matthew and Luke. In Double Tradition contexts, and in many of the unique Matthean and Lukan pericopae, it was often possible to translate the Greek text word for word into Hebrew. In Triple Tradition contexts, however, Lindsey observed the strange phenomenon that the Gospel of Luke often remained relatively easy to translate into Hebrew, whereas Matthew showed many of the same characteristics that caused Mark to be so difficult to translate. These observations caused Lindsey to suspect that the Synoptic Gospels were based on sources that had been translated from Hebrew into Greek in a highly literal fashion. These same observations caused Lindsey to question whether Mark could have been the basis for both Matthew and Luke, since it is difficult to explain how Luke could have come up with a more Hebraic, and consequently a seemingly more authentic, text if at these points he had been following the un-Hebraic text of Mark.

Another weakness of the theory of Markan Priority came to the attention of Robert L. Lindsey when he undertook a project to translate the Gospel of Mark into modern Hebrew.[6] Lindsey observed that the text of Mark was often much more difficult to translate into Hebrew than were the parallel texts of Matthew and Luke. In Double Tradition contexts, and in many of the unique Matthean and Lukan pericopae, it was often possible to translate the Greek text word for word into Hebrew. In Triple Tradition contexts, however, Lindsey observed the strange phenomenon that the Gospel of Luke often remained relatively easy to translate into Hebrew, whereas Matthew showed many of the same characteristics that caused Mark to be so difficult to translate. These observations caused Lindsey to suspect that the Synoptic Gospels were based on sources that had been translated from Hebrew into Greek in a highly literal fashion. These same observations caused Lindsey to question whether Mark could have been the basis for both Matthew and Luke, since it is difficult to explain how Luke could have come up with a more Hebraic, and consequently a seemingly more authentic, text if at these points he had been following the un-Hebraic text of Mark.

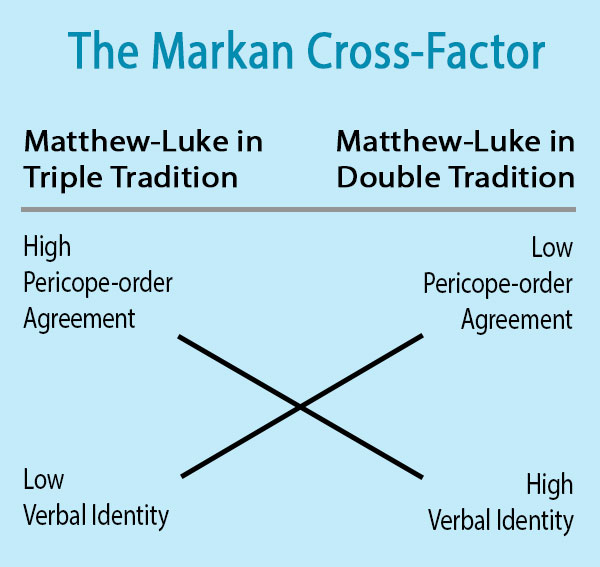

Pursuing the question further, Lindsey studied the patterns of verbal identity and pericope order that can be observed in the Synoptic Gospels. In the Triple Tradition, Lindsey observed a high level of agreement with respect to pericope order, but a low level of verbal identity. In the Double Tradition the reverse was often true: Matthew and Luke rarely agreed on the order of their pericopae, but many of their parallel passages showed a high degree of verbal identity. In other words, wherever Mark was present, all three Synoptic Gospels could reach general agreement with respect to pericope order, but could not reach agreement with respect to wording. On the other hand, wherever Mark was absent, Matthew and Luke were unable to agree with respect to pericope order, but were able to agree as to the wording in a significant number of their common pericopae. Lindsey referred to this phenomenon as the Markan Cross-Factor.[7]

Pursuing the question further, Lindsey studied the patterns of verbal identity and pericope order that can be observed in the Synoptic Gospels. In the Triple Tradition, Lindsey observed a high level of agreement with respect to pericope order, but a low level of verbal identity. In the Double Tradition the reverse was often true: Matthew and Luke rarely agreed on the order of their pericopae, but many of their parallel passages showed a high degree of verbal identity. In other words, wherever Mark was present, all three Synoptic Gospels could reach general agreement with respect to pericope order, but could not reach agreement with respect to wording. On the other hand, wherever Mark was absent, Matthew and Luke were unable to agree with respect to pericope order, but were able to agree as to the wording in a significant number of their common pericopae. Lindsey referred to this phenomenon as the Markan Cross-Factor.[7]

A New Approach to the Synoptic Gospels

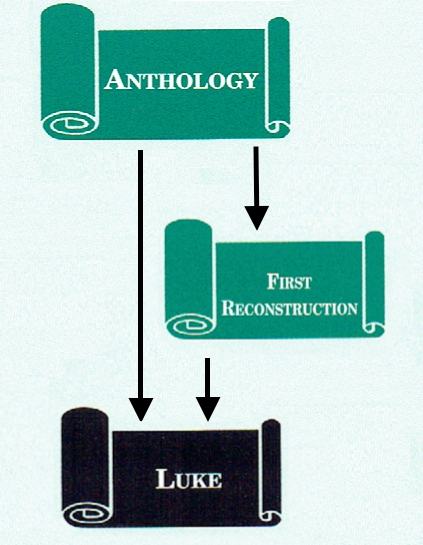

Luke’s sources according to Lindsey’s Hypothesis: The Anthology and the First Reconstruction. Illustration by Helen Twena.

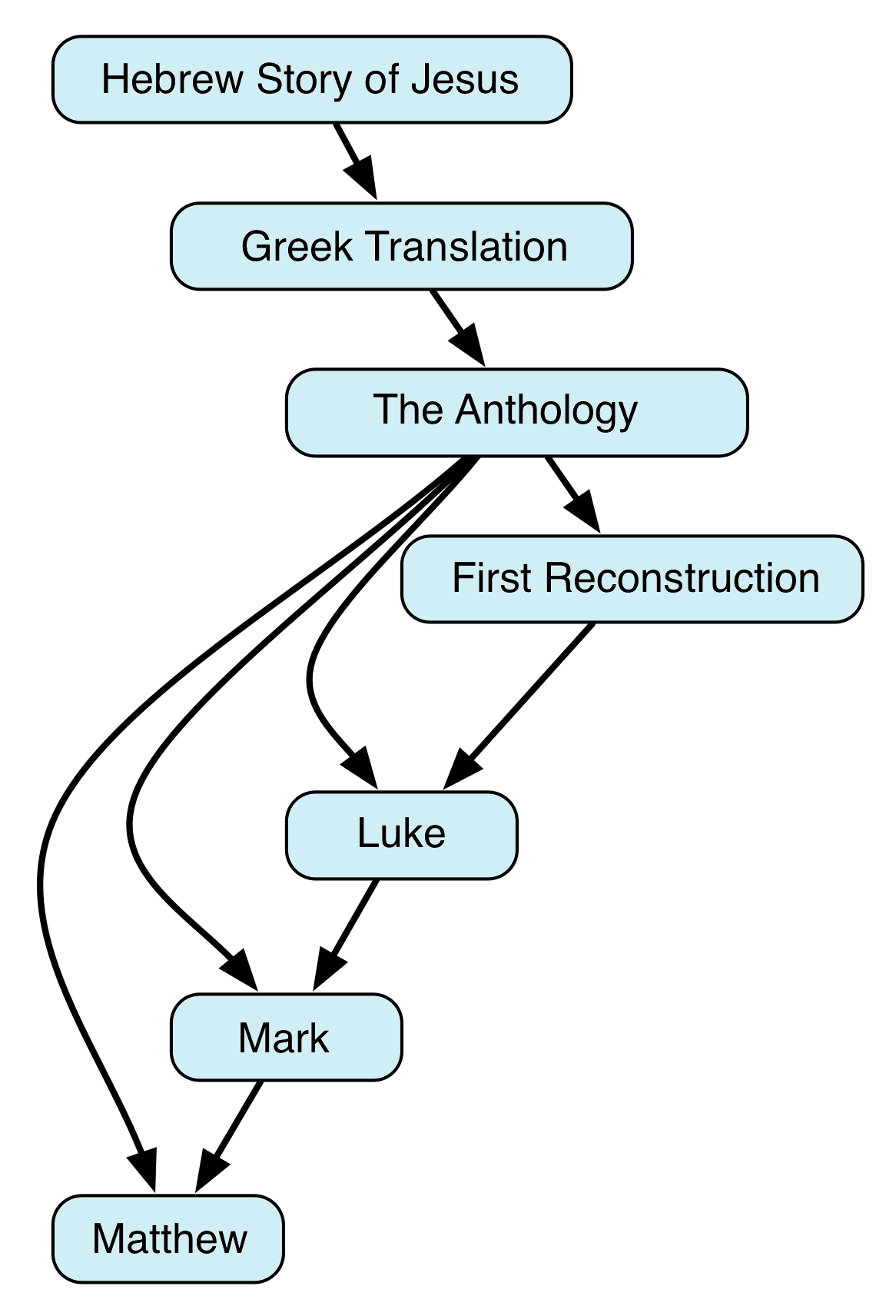

The evidence of the minor agreements of Matthew and Luke in Triple Tradition contexts, the Hebraic quality of Matthew and Luke in Double Tradition contexts, but the un-Hebraic quality of Mark and Matthew in Triple Tradition contexts as compared to Luke’s text, and the phenomenon Lindsey described as the Markan Cross-Factor, became the basis for a new solution to the Synoptic Problem that Lindsey proposed in 1963.[8] Although he was deeply indebted to the research of scholars who subscribed to theories of Markan or Matthean Priority, Lindsey proposed that Luke was the earliest of the Synoptic Gospels.[9] Luke had based his work on one or more Hebraic-Greek sources, which had descended from an original Hebrew biography of Jesus. This accounts for the Hebraic quality of Luke’s Gospel in both the Triple Tradition and the Double Tradition, as well as in much of his unique material.

Luke was followed by Mark who used Luke as the basis for his narrative outline, but who also knew one of Luke’s Hebraic-Greek sources as an independent witness. Lindsey referred to this source as the Anthology for reasons that will be explained below.

Mark’s sources according to Lindsey’s hypothesis: Luke and the Anthology. Illustration by Helen Twena.

Mark’s modus operandi was to rewrite the passages he borrowed from Luke partly on the basis of the Anthology, but more importantly by systematically substituting synonymns for Luke’s wording. These synonyms were derived from portions of Luke that Mark omitted, from Acts, from early Pauline Epistles, and from the Epistle of James. Mark’s practice of synonymic substitution and rewriting accounts for the un-Hebraic quality of his Gospel and the high degree of verbal disparity between Markan-Lukan parallels.[10]

Matthew’s sources according to Lindsey’s hypothesis: Mark and the Anthology. Illustration by Helen Twena.

Mark was followed by Matthew. Matthew used Mark as one of his two principal sources. Like Mark, Matthew also had access to the Anthology. Matthew accepted much of Mark’s narrative outline, but he often corrected Mark’s wording on the basis of the Anthology. Thus, it was because Matthew utilized one of Luke’s sources that Matthew and Luke were able to achieve minor verbal agreements against Mark despite their complete ignorance of each other’s work. The Anthology was also the source of the parallel passages with high verbal identity in Matthew and Luke that were not recorded in Mark. Evidently, the Anthology was not arranged in chronological order, and for this reason Matthew and Luke did not agree with respect to the placement of the Anthology’s pericopae not recorded in Mark, yet managed to achieve a high degree of verbal identity wherever Mark was not present to influence Matthew’s wording. Lindsey also supposed that the Anthology was the source of many of the unique Matthean and unique Lukan pericopae.[11]

As Lindsey continued to refine and develop his hypothesis, he reached the conclusion that although the Anthology was known to all three synoptic writers, Luke had access to a second source, which Lindsey referred to as the First Reconstruction. This refinement to Lindsey’s hypothesis came about through his study of the Lukan Doublets, sayings that appear twice in Luke in different contexts and slightly different forms. Lindsey observed that one set of the Lukan Doublets appeared to be collected into lists of pithy sayings, and that in these lists the doublets appeared in stylistically improved Greek in comparison to their counterparts. These counterparts did not appear in lists, but in longer teaching contexts, and these counterparts appeared to be more Hebraic in form. On the basis of these observations and others, Lindsey posited Luke’s dependence on two sources: the Anthology and the First Reconstruction.[12]

The source behind the Anthology according to Lindsey’s Hypothesis: a literal Greek translation of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua. Illustration adapted from Helen Twena.

Lindsey described the Anthology as having descended from a literal Greek translation of an original Hebrew biography of Jesus. Like the original Hebrew biography, the literal Greek translation was composed of numerous narrative-sayings complexes in which Jesus used incidents he observed as occasions for teaching his followers and the people who were involved in the incident. These narrative-sayings complexes were often marked by a similar form: (1) an incident, which gave rise to (2) a teaching, which was supported by (3) twin parables. The Anthologizer (the creator of the Anthology) separated these narrative-sayings complexes into smaller fragments and reorganized them, partly on the basis of genre. Incidents were collected into one section, teaching units were gathered into another section, and the parables were gathered into a third. Perhaps the Anthologizer separated the complexes into fragments for pedagogical purposes, or for the sake of memorization.

The First Reconstruction’s source according to Lindsey’s hypothesis: the Anthology. Illustration by Helen Twena.

The First Reconstruction, Luke’s conjectured second source, is the product of an editor who desired to place the Anthology’s fragments into a continuous narrative. This editor not only rearranged the Anthology’s material, but often improved its Greek style, interpreted the meaning of his source material for his non-Jewish, Greek-speaking audience, and removed many of the more glaring Hebraisms preserved in the Anthology. Luke derived much of his narrative outline from the First Reconstruction, and since Mark derived his outline from Luke, and Matthew derived his outline from Mark, the First Reconstruction exerted considerable influence on all three of the Synoptic Gospels, even though it was known directly only to Luke. Lindsey believed that by comparing Luke to the Anthology, Mark was able to detect Luke’s second source (the First Reconstruction), and Mark’s observation of Luke’s departure from the Anthology was an impetus for Mark’s editorial and redactional activity.

Positing the First Reconstruction as a second source for Luke’s Gospel also helped Lindsey to explain an anomaly he had observed: of the 42 Double Tradition pericopae, 18 exhibit high verbal identity, but the remaining 24 Double Tradition pericopae exhibit low verbal agreement.[13] Lindsey had explained the high verbal identity in the first set of Double Tradition pericopae by supposing that Luke and Matthew had used a common source, the Anthology. Lindsey was now able to explain the verbal disparity of the second set of Double Tradition pericopae by supposing that in these passages Luke depended on his second source (the First Reconstruction), whereas Matthew derived his parallel material from the Anthology.[14]

Thus, the basic tenet of Lindsey’s solution to the Synoptic Problem is that Luke was written first and was used by Mark, who in turn was used by Matthew, who did not know Luke’s Gospel. Lindsey’s theory postulates two non-canonical documents that were unknown to the Synoptists—a Hebrew biography of Jesus and a quite literal Greek translation of that original—and two other non-canonical sources—the Anthology and the First Reconstruction—known to one or more of the Synoptists.

| The two videos above offer an introductory explanation of how Robert Lindsey’s solution to the Synoptic Problem works and what his theory is able to explain. |

Goals of The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction

One of the goals of this commentary, which accepts Lindsey’s solution to the Synoptic Problem, is to demonstrate the fruitfulness of Lindsey’s approach when it is systematically applied to the nearly 200 pericopae discussed herein. Another goal of this commentary is to recover, insofar as possible, the narrative-sayings complexes that were the original context of the literary fragments that are preserved in the Synoptic Gospels. The main goal of this commentary, as the title implies, is to suggest a reconstruction of the original Hebrew biography of Jesus, which we refer to as the Life of Yeshua, and which ultimately stands behind each of the Synoptic Gospels and their sources. The purpose for achieving these goals, as stated at the outset, is to gain a clearer understanding of Jesus’ teachings and actions by attempting to trace the literary development of the traditions preserved in the Synoptic Gospels.

Because of its focus on the literary development of the Gospel traditions, the format of this commentary is quite different from most other Gospel commentaries. The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction is not organized according to the canonical order of Gospel stories, rather, the nearly 200 pericopae deemed to have descended from the earliest pre-synoptic source are arranged according to the conjectured order of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua.[15] The unique format reflects this commentary’s endeavor to offer a conjectured reconstruction of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua, the source from which we believe the Synoptic Gospels are ultimately derived.

Why Attempt a Reconstruction?

Bruce M. Metzger justified his writing of A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament as follows:

Most commentaries on the Bible seek to explain the meaning of words, phrases, and ideas of the scriptural text in their nearer and wider context; a textual commentary, however, is concerned with the prior question, What is the original text of the passage? That such a question must be asked—and answered!—before one explains the meaning of the text arises from two circumstances: (a) none of the original documents of the Bible is extant today, and (b) the existing copies differ from one another.

Despite the large number of general and specialized commentaries on the books of the New Testament, very few deal adequately with textual problems.[16]

The reconstruction presented in The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction goes even deeper than a textual commentary. Here, an attempt is made to recover the conjectured Hebrew words of Jesus’ biography, and the conjectured Greek words of its first translation. The reconstruction is also, like Luke’s Gospel (see Luke 1:1-4), an attempt to restore the original form of discomposed stories about Jesus. Consequently, this commentary not only attempts to reconstruct the earliest wording of the biography (linguistic reconstruction), but also attempts to gather together into “teaching complexes” (literary reconstruction) as many stories as possible from the conjectured biography.

At such a great distance from the historical events of Jesus’ life and from the earliest accounts in which these events were described, we cannot hope to succeed perfectly in our efforts to reconstruct the order of the stories of the primitive biography of Jesus. Nevertheless, like the exercise of reconstructing Hebrew phrases from the Greek texts of the Synoptic Gospels, the exercise of associating Gospel sayings and passages now found in distant locations within a particular Gospel (and often in different contexts from one Synoptic Gospel to another), and placing them into new contexts based on thematic and linguistic congruency, yields many new insights. Such attempts at associating passages found scattered in the Synoptic Gospels often enable one to gain startling new insights into the acts of Jesus and better understand the meaning of his sayings.[17] The work of linguistic and literary reconstruction is a scholarly exercise in linguistic and textual archaeology aimed at “unearthing,” where possible, the earlier accounts of Jesus’ life and teaching.

“Back-translation” is one of many tools employed by disciples of Robert Lindsey, David Flusser and Shmuel Safrai in analyzing the Gospel texts. Back-translating helps us to decide what words may have been part of the Hebrew story and its Greek translation from which the canonical Greek Gospels derived. If a Greek Gospel text translates easily and naturally to Hebrew, we take this as an indication that it may reflect the text of the conjectured Hebrew gospel. On the other hand, if a Greek passage in the Synoptic Gospels is difficult or impossible to translate into Hebrew, we suspect that it may have been amended by Matthew, Mark or Luke, or the Greek editor of one of their sources. When we analyze a Greek text of the canonical Gospels, we may often simultaneously create a mental image of the surmised Greek and Hebrew undertexts and compare, analyze and weigh them.

Why Reconstruct the Life of Yeshua in Hebrew, Not Aramaic?

Wouldn’t the early Life of Yeshua have been written in Aramaic? Probably not.

For over a century the prevailing opinion among New Testament scholars has been that Jesus’ teachings were originally delivered in Aramaic.[18] Recent discoveries, however, have begun to undermine this scholarly assumption. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, written in the century prior to Jesus’ lifetime, and of the Bar-Kochva letters, written in the century after Jesus, show that Hebrew was a living language in the first century and could be used for a wide range of purposes, from Bible commentary and liturgical texts to military communications and legal documents. Judean coins from the period of the Great Revolt and of the Bar-Kochva Revolt also bear Hebrew inscriptions.[19]

David Flusser on Jesus’ Use of Aramaic

The earliest layer of rabbinic literature was mainly composed in Hebrew.[20] Many rabbinic traditions preserved in Hebrew date to the end of the Second Temple period. Certain phrases in the Gospels, like “the Kingdom of Heaven,” are unparalleled in Jewish literature except for rabbinic sources preserved in Hebrew. It is also a significant fact that the literary genre of parables exists only in the Gospels and rabbinic literature, and all rabbinic parables are recorded in Hebrew.[21] Given this circumstantial evidence, the likelihood that Jesus taught in Hebrew rather than Aramaic should be preferred.

There is also direct testimony concerning the original language of Jesus’ teaching that must be considered. Papias (ca. 70-160 C.E.) wrote that Ματθαῖος…Ἑβραΐδι διαλέκτῳ τὰ λόγια συνετάξατο (“Matthew…arranged the sayings [of Jesus] in the Hebrew language”; Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.39.16).[22] Since Papias cannot have been referring to the canonical Gospel of Matthew, which was composed in Greek and was heavily influenced by the Gospel of Mark, it is likely that Papias’ testimony refers to the original Hebrew Life of Yeshua, which Papias claims was written by the apostle Matthew, an eyewitness to Jesus’ life. There is little reason not to accept this early tradition.[23]

One also has to consider the internal evidence of the Gospels. Significant portions of the Synoptic Gospels, particularly of Luke and those portions of Matthew not influenced by Mark, can often be translated word for word into Hebrew.[24] Some kind of reasonable explanation must be found to account for this remarkable phenomenon. This commentary will attempt to demonstrate the merits of Lindsey’s hypothesis that behind the Greek text of the Synoptic Gospels there ultimately stands a Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

Guiding Principles

In order to understand the procedure this commentary will follow, it is necessary to set down the presuppositions upon which it operates:

- The Greek Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke descended from a Hebrew biography of Jesus of Nazareth, which we refer to as the Life of Yeshua. The Hebrew biographer often organized his work into teaching “complexes.” Each complex was a literary unit that consisted of a narrative description of an incident in Jesus’ life, and Jesus’ teaching given in response to that incident.

- The Hebrew biography was translated into Greek soon after it was composed.[25] This translation was so literal that the resultant Greek was often unidiomatic. The Greek translation preserved the teaching complexes intact.

- The Greek translation of the Hebrew biography was reorganized by an editor who broke the teaching complexes apart into fragments. These fragments were then collected according to genre and presented in an Anthology of Jesus’ teachings and activities. Despite the discomposure of the teaching complexes and the transfer of the resulting fragments to new contexts, the Anthology preserved the highly Hebraic-Greek style of the earlier Greek translation of the Hebrew biography of Jesus.

- The Anthology was abridged. Lindsey called this abridgment the First Reconstruction because it was an attempt, even before similar attempts by Matthew, Mark and Luke, to construct a continuous narrative from the literary fragments preserved in the Anthology. In addition, the First Reconstructor (the creator of the First Reconstruction) attempted to improve the Anthology’s very unidiomatic Greek.

- The order in which the Synoptic Gospels were written is Luke→Mark→Matthew.

- Luke used the Anthology (Luke’s Source 1) and the First Reconstruction (Luke’s Source 2) as the two principal sources for his Gospel. The First Reconstruction provided Luke’s narrative skeleton, in other words, it provided Luke’s chronology. Into that framework Luke spliced many additional stories from the Anthology not included in the First Reconstruction. Luke’s procedure (in contrast to Matthew’s) was to quote his sources in blocks rather than attempt to harmonize them, thus allowing us to distinguish between them through careful literary and linguistic analysis.

- Mark knew the Anthology and Luke, but used Luke as his source almost exclusively. Apparently, this preference was due to Mark’s observation of chronological order in Luke’s Gospel, something that was lacking in the Anthology. Consequently, Mark generally followed Luke’s story order, while making many changes to Luke’s wording.

- Matthew used Mark and the Anthology, but did not know Luke’s Gospel. Matthew depended heavily on Mark for the same reason that Mark depended so heavily on Luke—he saw chronological order in Mark’s Gospel. Like Luke, Matthew spliced many additional stories from the Anthology into Mark’s chronological framework. Since the Anthology had little or no story order, and since Matthew did not know Luke’s Gospel, Matthew’s placement of the stories he copied from the Anthology differs greatly from Luke’s placement of the same stories.

- In attempting to restore the pre-synoptic Greek and Hebrew versions of the Life of Yeshua, this commentary approaches the Greek texts of canonical Matthew, Mark and Luke with the above presuppositions, but, for practical purposes, the first order of business is to determine how Hebraic is the Greek text presented by each synoptic writer. If, for example, Matthew has the more Hebraic phrase, Matthew’s version is accepted. The same is true when approaching the texts of Mark and Luke. The Greek text of each of the Synoptic Gospels is tested every step of the way, and the text that goes back most smoothly into Hebrew is selected. This independent Hebrew control, which is one of the distinctive features of the Jerusalem School’s approach,[26] provides a check against arbitrarily preferring one Gospel’s reading over another, and, perhaps even more importantly, guards against allowing one’s synoptic theory to dictate the outcome of one’s analysis.

The attempt to reconstruct the Hebrew source behind the Synoptic Gospels raises an intriguing question: Was Jesus’ biography originally recorded in Biblical or Mishnaic Hebrew? Most disciples of Lindsey, Flusser and Safrai agree that the narrative portions of the Hebrew story were probably tended toward a biblicizing style of Hebrew, while the style of the dialogue was more Mishanic.[27] But the distinction was probably not hard and fast. In narrative portions post-Biblical Hebrew vocabulary and expressions occasionally crept in (as sometimes happened in the biblicizing Hebrew of the DSS and in the baraita in b. Kid. 66a,[28] which preserves a late Second Temple period Hebrew source composed in a biblicizing style).[29] Likewise, archaic Hebrew probably occurred in direct speech when the speaker wished to allude to Scriptural concepts or specific verses. Nevertheless, direct speech was mainly mishnaic in style since there are expressions in the Synoptic Gospels, such as σὰρξ καὶ αἷμα (“flesh and blood”; Matt. 16:17 [= בָּשָׂר וָדָם]),[30] and ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν (“kingdom of Heaven”; Matt. 16:19 [= מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם]), that do not occur in Biblical Hebrew. Thus, in the Life of Yeshua we have reconstructed the Hebrew text using a mixture of Biblical (mainly in narrative) and Mishnaic (mainly in dialogue) Hebrew, a style Lindsey advocated in his research.[31]

Why “The Life of Yeshua”?

Like סֵפֶר דִּבְרֵי שְׁלֹמֹה (sēfer divrē Shlomoh, “Scroll of the words of Solomon”)[32] mentioned in 1 Kgs. 11:41, סֵפֶר דִּבְרֵי הַיָּמִים לְמַלְכֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל (sēfer divrē hayāmim lemalchē Yisrā’ēl, “Scroll of the words of the days of the kings of Israel”) mentioned in 1 Kgs. 14:19, סֵפֶר דִּבְרֵי הַיָּמִים לְמַלְכֵי יְהוּדָה (sēfer divrē hayāmim lemalchē Yehūdāh, “Scroll of the words of the days of the kings of Judah”) mentioned in 1 Kgs. 14:29, and the book of Tobit, which begins with βίβλος λόγων Τωβιθ (biblos logōn Tōbith, “Book of the words of Tobit”),[33] the conjectured Hebrew source from which the Synoptic Gospels are descended may have been entitled סֵפֶר דִּבְרֵי יֵשׁוּעַ (sēfer divrē Yēshūa‘, “Scroll of the words of Jesus”). Why, then, have we entitled this work The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction rather than “The Scroll of the Words of Jesus: A Suggested Reconstruction?”

The first part of our answer is that “Scroll of the Words of Jesus” not only makes for a cumbersome title, but the overly literal translation fails to capture the meaning of דִּבְרֵי (divrē, “words of”) in the title. Each of the books whose title began with “Scroll of the Words of…” contained much more than a collection of sayings—they chronicled the entire reigns of kings or told the full story of the main character. A more dynamic translation would be “Scroll of the Acts and Sayings of Jesus,” but this too is rather cumbersome. “Life of” succinctly captures the essence of the conjectured Hebrew title of Jesus’ biography.

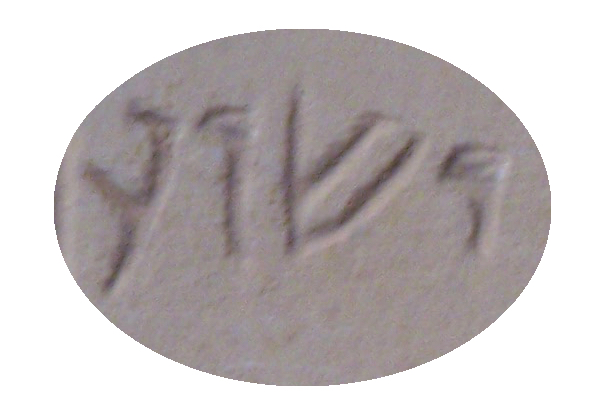

The name yēshūa‘ as it appears on a first-century ossuary discovered in Jerusalem (Rahmani no. 702). Photographed at the Israel Museum by Joshua N. Tilton.

And what about “Yeshua” in the title? יֵשׁוּעַ (yēshūa‘), a shortened form of the biblical יְהוֹשׁוּעַ (yehōshūa‘, “Joshua”),[34] was almost certainly the form of the name given to Jesus at his circumcision (Luke 2:21) by his parents, Joseph (Yosef) and Mary (Miryam).[35] Since our goal is to reconstruct the conjectured Hebrew biography of Jesus, we feel that using a Hebraic form of his name in the title is a convenient way to signal this commentary’s unique endeavor. For the same reason, we have used Hebraic names (e.g., Yohanan instead of John) in the pericope titles. Our dynamic translations also feature Hebraic names to signal that the dynamic translation is a translation of the Hebrew reconstruction.

Referring to Jesus as Yeshua also serves another useful function. Since יֵשׁוּעַ (Yēshūa‘) is usually spelled “Jeshua” and not “Jesus” in most English versions of the Hebrew Scriptures (for example, in Ezra 2:2 and 2 Chr. 31:15), these Bible translations can easily give the mistaken impression that Jesus’ name was unique. The truth, however, is quite the reverse. The name Yeshua was borne by at least five different persons in the Hebrew Scriptures.[36] By the first century C.E., Yeshua had become one of the most popular Jewish personal names.[37] Even in the New Testament we find another individual with the name Jesus (Col. 4:11). In order to correct the false impression that Jesus’ name was unique and to emphasize his Jewish identity and his solidarity with the people of Israel, we have chosen to refer to Jesus by his Hebrew name in the title of this work, a name he shared with many of his contemporaries: Yeshua.[38]

Codex Vaticanus or an Eclectic Text?

There are approximately 1,000 extant Greek manuscripts containing all or part of the Gospels. We have printed the text of Codex Vaticanus[39] for Matthew, Mark and Luke (Columns 1, 2 and 3) since this manuscript is usually regarded as the best of the major witnesses to the Gospels. During the past 350 years textual critics have collated the Greek manuscripts of the Synoptic Gospels. The result has been the production of eclectic texts such as the Nestle-Aland edition of the New Testament (Novum Testamentum Graece). The majority of readings in these scholarly editions are very sure (for example, there exist no variant manuscript readings for 642 [59.9%] of Matthew’s 1,071 verses, for 306 [45.1%] of Mark’s 678 verses, and for 658 [57.2%] of Luke’s 1,151 verses); however, an eclectic text is not identical to any existing manuscript. A scholar who wishes to ignore the evidence of the Lukan-Matthean minor agreements might appeal to variant readings in manuscripts of Matthew or Luke to disqualify many of these agreements. Since we have chosen to follow Codex Vaticanus, a real text, we are prevented from this kind of manipulation.

Arrangement of the Reconstruction

Within each section of the Life of Yeshua (LOY) commentary there will be a link to the reconstructed text for that pericope. Readers should refer to this reconstruction as they study the commentary.

Within each section of the Life of Yeshua (LOY) commentary there will be a link to the reconstructed text for that pericope. Readers should refer to this reconstruction as they study the commentary.

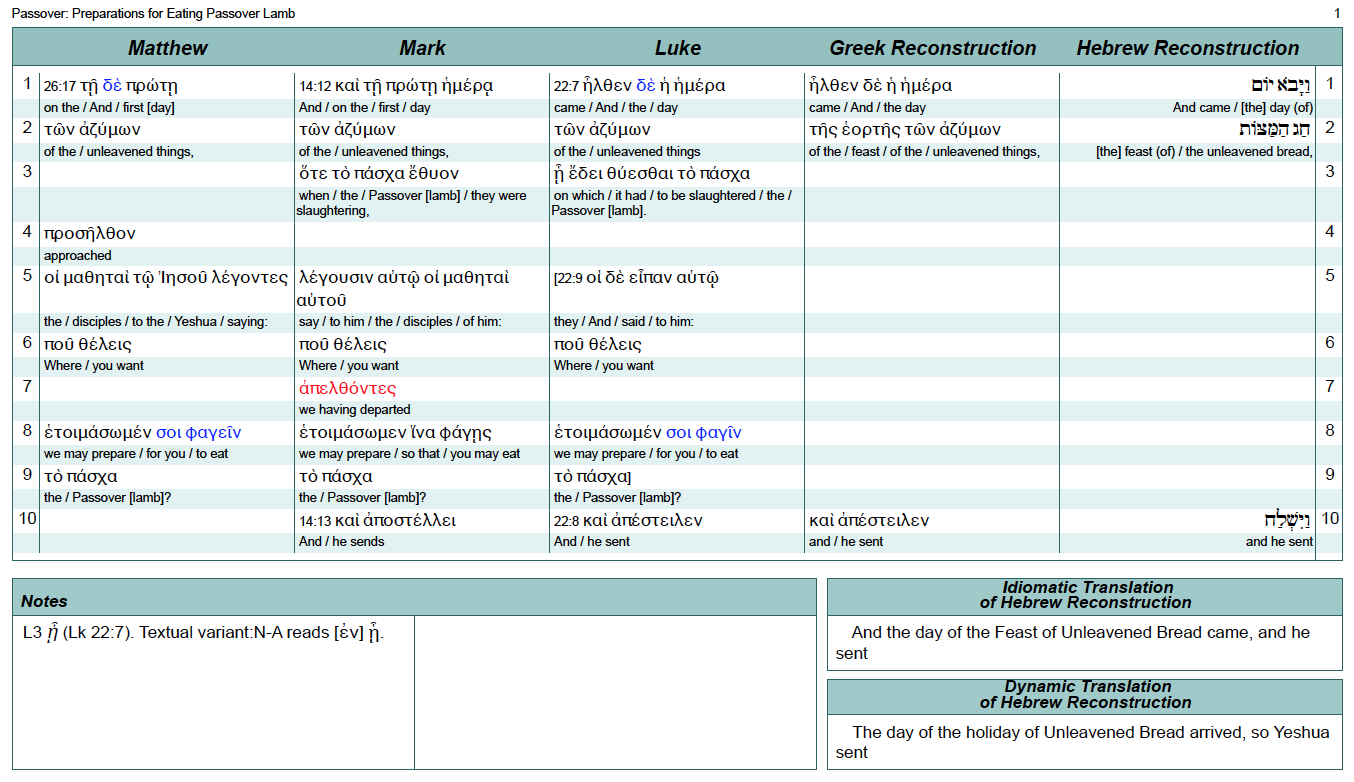

The upper panel of each page of the reconstruction contains five major columns: four columns of Greek and one column of Hebrew. (The numbers in the narrow far-left and far right columns at the beginning of each line are simply line designations for the Greek and Hebrew texts and are completely arbitrary.) Beginning in the upper left, from left to right, the first three columns contain the texts of the Synoptic Gospels, arranged in their traditional order: Matthew, Mark and Luke. The fourth column contains our Greek reconstruction of the Anthology, the most ancient of the conjectured pre-synoptic sources known to any of the authors of the canonical Gospels.[40] The fifth column contains a reconstruction of the conjectured Hebrew source we refer to as Life of Yeshua. Note that our arrangement of these columns roughly corresponds to the stages of Gospel transmisson as Lindsey described them. Closest to the reconstructed text of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua is the reconstruction of the Greek translation of the Life of Yeshua as preserved in the Anthology. Closest to the Anthology is Luke, followed by Mark, followed by Matthew. Running horizontally below each line of the Greek and Hebrew texts in each of the five columns is an interlinear, literal English translation, which makes it possible for readers who have no knowledge of Greek or Hebrew to follow the reconstruction process.

The bottom panel of each page is made up of three sections. General notes are presented on the left. These are usually brief comments about the Greek text, such as notes about spelling differences between Codex Vaticanus and the 27th Nestle-Aland edition, or variant readings in other ancient Greek MSS. To the right of the notes are boxes for two additional levels of English translation of the Hebrew reconstruction: an idiomatic translation which is as literal as possible while still being acceptable English, and a dynamic translation reflecting what a modern English-speaker might have written had he originally recorded the story.

Brackets within the reconstruction serve two purposes:

- within the texts of Matthew, Mark and Luke they indicate verses or parts of verses that have been duplicated and moved from their canonical location. This is done to highlight synoptic parallels. The bracketed words are also retained in their canonical location, but without brackets;

- brackets are employed in the interlinear and idiomatic English translations to indicate words that are not found in the Greek or Hebrew, but are necessary for the English sense.

In order to identify the Lukan-Matthean minor agreements against Mark in Triple Tradition pericopae, font colors are utilized. In the Matthew and Luke columns, blue coloring identifies minor agreements. There also exist in the Triple Tradition Lukan-Matthean agreements of omission, where Mark uses a word or phrase that is absent in the parallels of both Matthew and Luke. (At these points, Matthew and Luke agree to disagree with Mark by omitting words of Mark’s text.) Red coloring in the Mark column identifies such Markan additions.

A Word of Thanks

David Bivin and his co-author, Joshua Tilton, wish to express their gratitude and appreciation (in alphabetical order) to:

- Lauren Asperschlager, for her diligent and meticulous work as copy editor for The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction.

- Brian Becker, for his technical support and counsel. Brian created the Jerusalem Perspective website in the 1990s at the dawn of the age of personal computers, and continues to recreate the site as new technologies become available.

- Dr. Randall Buth, for his constructive criticism of our Greek and Hebrew reconstructions. Buth’s expertise in biblical languages makes his input invaluable.

- Pieter Lechner, who assisted David in brainstorming the layout of the reconstruction, and continues to advise us on every aspect of the project, including technical comments about the content of the commentary.

- Linda Pattillo for designing the trilingual templates on the Mellel platform with which we publish the reconstructions of the Life of Yeshua. Linda devoted hundreds of hours to the project, and we are extremely grateful to her.

Special thanks also are due to the creators of the Mellel word processor (www.mellel.com), Eyal and Ori Redler and Guy Hivroni. For ten years (1992-2002) David’s efforts to publish The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction were stymied because no word processor or layout program could be found that would allow Hebrew, Greek and English to be displayed in parallel columns or to be manipulated within these columns in the way David envisioned. However, Mellel has made David’s dream possible.

Finally, we wish to recognize the continuous yet cheerful efforts of the librarians at the Curtis Memorial Library in Brunswick, Maine and the librarians at the Rockland Public Library in Rockland, Maine, who have been so helpful in obtaining books and articles for Joshua’s research.

DedicationThe Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction is dedicated to the memory of Robert L. Lindsey. |

Abbreviations

General Abbreviations

- ∥ = parallel

- 1 Acts = Acts 1:1-15:34

- 2 Acts = Acts 15:35-28:31

- א = Codex Sinaiticus

- יי = We use the abbreviation יי to represent the Tetragrammaton wherever it appears in primary sources or in our Hebrew reconstruction.

- A = Codex Alexandrinus

- AB = Anchor Bible

- alt. = alternative, alternatively

- Anth. = the Anthology, the first of Luke’s two conjectured extracanonical sources (and, along with the canonical Gospel of Mark, one of Matthew’s two sources), displayed very Hebraic Greek.

- Aram. = Aramaic

- B = Codex Vaticanus

- BH = Biblical Hebrew[41]

- cent. = century

- chpt(s). = chapter(s)

- conj. = conjunction

- CRINT = Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum

- D = Codex Bezae

- dat. = dative

- DSS = the Dead Sea Scrolls

- DT = the Double Tradition

- ed. = edition; editor; edited by

- Eng. = English

- esp. = especially

- FR = the First Reconstruction, a revision and abridgment of Anth. FR is the second of Luke’s two conjectured extracanonical sources.

- frag. = fragment

- Gk. = Greek

- GR = the Greek reconstruction

- HB = the Hebrew Bible

- Heb. = Hebrew, Hebraic

- HR = the Hebrew reconstruction

- incl. = including

- Jos. = Josephus

- Kaufmann = the Kaufmann manuscript of the Mishnah.[42] This is the Mishnah manuscript that is cited throughout this work unless otherwise noted.

- κ.τ.λ. = και τα λοιπά (kai ta loipa, “and the rest”), the Greek equivalent to &c. or etc., used in abbreviated quotations of Greek text.

- L = line(s). The LOY reconstructions are broken down into small grammatical units, each of which occupies a single line in the reconstruction documents. The far left- and right-hand columns of the reconstruction panels contain the line numbers.

- Lat. = Latin

- lit. = literally

- Loeb = Loeb Classical Library

- LOY = Life of Yeshua

- LXX = the Septuagint

- MH = Middle (Mishnaic) Hebrew[43]

- MS(S) = manuscript(s)

- MT = the Masoretic Text

- NT = the New Testament

- 𝔓 = papyrus

- pace = (Lat., “with peace”) signals respectful disagreement

- Pseud. = Pseudepigrapha

- SG = the Synoptic Gospels

- TT = the Triple Tradition

- trans. = translation; translator; translated by

- U = unique (a pericope found in only one of the Synoptic Gospels)

- var. = variant

- WBC = Word Biblical Commentary

- x(x) = time(s)

Grammatical abbreviations

- abs. = absolute

- acc. = accusative

- act. = active

- adj. = adjective

- adv. = adverb

- aor. = aorist

- art. = article

- def. = definite

- dir. obj. = the Hebrew accusative particle אֵת, which typically precedes a definite direct object.

- fem. = feminine

- fut. = future tense

- gen. = genitive

- hist. pres. = historical present

- impf. = imperfect

- impv(s). = imperative(s)

- impsnl. = impersonal

- indic. = indicative

- inf. = infinitive

- masc. = masculine

- nom. = nominative

- neut. = neuter

- opt. = optative

- pass. = passive

- per. = person

- perf. = perfect

- plur. = plural

- poss. = possessive

- prep. = preposition

- pres. = present

- pron. = pronoun

- ptc. = participle

- sing. = singular

- subjv. = subjunctive

- subst. = substantive

- voc. = vocative

Ancient Sources

Abbreviations for rabbinic sources are listed below:

Abbreviations for all other ancient sources follow the SBL Handbook of Style.[44]

Bibliography

Primary Sources (Texts and Translations)

- Blackman = Philip Blackman, trans., Mishnayoth (7 vols.; London: Mishnah Press, 1951-1956).

- Blunt = A. W. F. Blunt, ed., The Apologies of Justin Martyr (Cambridge Patristic Texts; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1911).

- Braude-Kapstein = William G. Braude and Israel J. Kapstein, trans., Tanna Debe Eliyyahu: The Lore of the School of Elijah (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1981).

- Buber = Salomon Buber, ed., Midrasch Tanchuma (2 vols.; Wilna, 1885; repr., Jerusalem, 1963).*

- __________, ed. Midrash TehillimWilna, 1891; repr., Jerusalem, 1976).*

- __________, ed. Midrasch Echah Rabbati [Lamentations Rabbah] (Wilna, 1899).

- __________, ed. Agadath Bereschith (Krakau: Fischer, 1902).

- Charles = R. H. Charles, The Greek Versions of the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs (Oxford: Clarendon, 1908).

- Charlesworth = James H. Charlesworth, ed., The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (2 vols.; New York: Doubleday, 1983-1985).

- Danby = Herbert Danby, trans., The Mishnah: Translated from the Hebrew with Introduction and Brief Explanatory Notes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933).

- DSS Study Edition = Florentino García Martínez and Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar, eds. The Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition (2 vols.; Leiden: Brill, 1997-1998).

- Epstein-Melamed = J. N. Epstein and E. Z. Melamed, Mekhilta d’Rabbi Šim‘on b. Jochai (Jerusalem: Mekize Nirdamim, 1955; repr., Jerusalem: Hillel, 1980).

- Etelsohn = Baruch Etelsohn, ed., Kanfe Yonah: Midrash Rabbah on Song of Songs (Warsaw, 1876).

- Finkelstein = Louis Finkelstein, ed., Sifre on Deuteronomy (New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 2001).

- Friedmann = M. Friedmann (Meir Ish-Shalom), ed., Pesikta Rabbati (Vienna, 1880).

- __________ = M. Friedmann (Meir Ish-Shalom), ed., Seder Eliyahu Rabba und Seder Eliahu Zuta (Tanna d‘be Eliahu) (Vienna: Ahiasaf, 1902).

- __________ = M. Friedmann (Meir Ish-Shalom), ed., Pseudo-Seder Eliahu zuta (Vienna, 1904).

- Goldin = Judah Goldin, trans., The Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1955).

- Guggenheimer = Heinrich W. Guggenheimer, trans., Seder Olam: The Rabbinic View of Biblical Chronology (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005).

- Guillaumont = A. Guillaumont, H.-CH. Puech, G. Quispel, W. Till and Yassah ‘Abd Masīḥ, The Gospel According to Thomas: Coptic Text Established and Translated (Leiden: Brill; New York: Harper & Row, 1959).

- Hammer = Reuven Hammer, trans., Sifre: A Tannaitic Commentary on the Book of Deuteronomy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986).

- Higger = Michael Higger, ed., Massechtot Zeirot (New York: Monolin Press, 1929).*

- __________ = Michael Higger, ed., Seven Minor Treatises (New York: Bloch, 1930).

- __________ = Michael Higger, ed., The Treatises Derek Erez: Masseket Derek Erez, Pirke Ben Azzai, Tosefta Derek Erez (New York: DeBei Rabanan, 1935).**

- __________ = Michael Higger, ed., Massekhet Sofrim (New York: DeBei Rabanan, 1937).

- Hirshman = Marc Hirshman, ed., Midrash Kohelet Rabbah 1-6 Critical Edition Based On Manuscripts and Genizah Fragments (Jerusalem: Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, 2016).*

- Horovitz = H. S. Horovitz, Sifre d’be Rab: Fasciculus Primus: Sifre ad Numeros adjecto Sifre zutta (Frankfurt: J. Kaufmann, 1917).

- Howard = George Howard, ed. and trans., Hebrew Gospel of Matthew (Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press, 1995).

- Kiperwasser = Reuven Kiperwasser, ed., Midrashei Kohelet: Kohelet Rabbah 7-12; Kohelet Zuta 7-9: Critical Edition Based on Manuscripts and Geniza Fragments (Jerusalem: Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, 2021).*

- KJV = The King James (or Authorised) Version of the Bible

- Lauterbach = Jacob Z. Lauterbach, ed. and trans., Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael (2 vols.; 2d ed.; Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2004).

- Loeb = Flavius Josephus, Works (trans. H. St. J. Thackeray et al.; Loeb Classical Library; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1926-1965).

- __________ = Philo, Works (trans. F.H. Colson et al.; Loeb Classical Library; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1929-1953).

- Mandelbaum = Bernard Mandelbaum ed., Pesikta de Rav Kahana (2 vols.; New York: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1962).

- Margulies = Mordecai Margulies, ed., Midrash Wayyikra Rabbah: A Critical Edition Based on Manuscripts and Genizah Fragments with Variants and Notes (2 vols.; New York and Jerusalem: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1993).**

- Merkin = Moshe A. Merkin, ed., Midrash Rabbah (11 vols.; Tel Aviv: Yavneh, 1956-1967).

- MHNT = Modern Hebrew New Testament (Jerusalem: The Bible Society in Israel, 1976, 1991).

- N-A = Eberhard Nestle, Erwin Nestle, Barbara Aland and Kurt Aland, eds., Novum Testamentum Graece (27th ed.; Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelstiftung, 1993).

- Nestle-Aland = See N-A.

- NETS = A New English Translation of the Septuagint (ed. Albert Pietersma and Benjamin G. Wright; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- Neusner = Jacob Neusner, trans., The Mishnah: A New Translation (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1988).

- __________ = Jacob Neusner, trans., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew with a New Introduction (2 vols.; Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2002).

- __________ = Jacob Neusner, trans., The Jerusalem Talmud : A Translation and Commentary on CD (39 vols.; Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2009)

- NIV = New International Version of the Bible

- NRSV = New Revised Standard Version of the Bible

- Odeberg = Hugo Odeberg, ed., trans., 3 Enoch or The Hebrew Book of Enoch (New York: Ktav, 1973).

- Oxford Annotated Mishnah = Shaye J. D. Cohen, Robert Goldenberg and Hayim Lapin, eds., The Oxford Annotated Mishnah: A New Translation of the Mishnah With Introductions and Notes (3 vols.; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022).*

- Schechter = Solomon Schechter, ed., Aboth de Rabbi Nathan: Edited from Manuscripts with an Introduction, Notes and Appendices (2d ed.; New York: Philipp Feldheim, 1967).

- Soncino = The Babylonian Talmud (ed. Isidore Epstein; London: Soncino, 1935-1952).

- __________ = The Midrash Rabbah (ed. H. Freedman and Maurice Simon; 3d ed.; 10 vols.; London: Soncino, 1983).

- Tabory-Atzmon = Joseph Tabory and Arnon Atzmon, eds., Midrash Esther Rabbah: Critical Edition Based on Manuscripts (Jerusalem: Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, 2014).**

- Theodor-Albeck = Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds., Bereschit Rabba (3 vols.; Berlin: M. Poppelaur, 1912-1936).**

- Trollope = William Trollope, ed., S. Justini Philosophi et Martyris Cum Tryphone Judæo Dialogus (2 vols.; Cambridge: J. Hall, 1846-1847).

- VanderKam, Jubilees = James C. VanderKam, Jubilees: A Commentary (2 vols.; Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2018).*

- Weiss = Isaac H. Weiss, ed., Sifra (Jacob Schlossberg: Wien, 1862).

- Zlotnick = Dov Zlotnick, ed., The Tractate “Mourning” (Semahot): Regulations Relating to Death, Burial, and Mourning (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966).

- Zuckermandel = Moshe Zuckermandel, Die Tosefta nach den Erfurter und Wiener Handschriften mit Parallelstellen und Varianten (Trier: Pasewalk, 1880; repr., Jerusalem: 2004).

Secondary Sources (Commentaries, Reference Works, Scholarly Studies)

- Abbott, Clue = Edwin A. Abbott, Clue: A Guide Through Greek to Hebrew Scripture (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1900).

- Abbott, Corrections = __________, The Corrections of Mark Adopted by Matthew and Luke (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1901).

- Abbott, Fourfold = __________, The Fourfold Gospel (5 vols.; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1913-1917).

- ABD = David Noel Freedman, ed., Anchor Bible Dictionary (6 vols.; New York: Doubleday, 1992).

- Abrahams = Israel Abrahams, Studies in Pharisaism and the Gospels (2 vols.; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1917-1924).

- Aland = Kurt Aland, ed., Synopsis Quattuor Evangeliorum (Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 1963ff.).

- Albright-Mann = William Foxwell Albright and C. S. Mann, Matthew (AB 26; Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1971).

- Allen, Matt. = Willoughby C. Allen, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to St. Matthew (ICC; 3d ed.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1912 [orig. pub. 1907]).

- Allen, Mark = __________, The Gospel According to Mark (London: Rivingtons, 1915).

- Bacon = Benjamin Wisner Bacon, The Beginnings of Gospel Story (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1909).

- Bailey = Kenneth E. Bailey, Poet and Peasant and Through Peasant Eyes: A Literary-Cultural Approach to the Parables in Luke (Combined Edition; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983).

- BDAG = Walter Bauer, Frederick W. Danker, William F. Arndt, and F. Wilbur Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (3d ed.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000).

- BDB = Francis Brown, S. R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament (London: Clarendon Press, 1906; repr., Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2000).

- Beare, Earliest = Francis Wright Beare, The Earliest Records of Jesus (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1962).

- Beare, Matt. = __________, The Gospel of Matthew: Translation, Introduction and Commentary (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1981).

- Bendavid = Abba Bendavid, Biblical Hebrew and Mishnaic Hebrew (2 vols.; Tel Aviv: Dvir, 1967-1971) (Hebrew).

- Betz = Hans Dieter Betz, The Sermon on the Mount: Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995).

- Black = Matthew Black, An Aramaic Approach to the Gospels and Acts (2d ed.; Oxford: Clarendon, 1954).

- Bock = Darrell L. Bock, Luke (IVPNT; Downers Grove, Il.: IVP Academic, 1994).

- Boring-Berger-Colpe = M. Eugene Boring, Klaus Berger, and Carsten Colpe, Hellenistic Commentary to the New Testament (Nashville: Abingdon, 1995).

- Bovon = François Bovon, Luke: Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (3 vols.; trans. Donald S. Deer [Evangelium nach Lukas, 1989-2009]; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002, 2013, 2012).

- Brown = Raymond E. Brown, The Gospel According to John (2 vols.; Anchor Bible 29 and 29a; Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1966, 1970).

- A. B. Bruce = Alexander Balmain Bruce, The Synoptic Gospels (6th ed.; Expositors Greek Testament; London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1910 [orig. pub. 1897]).

- F. F. Bruce = F. F. Bruce, The Hard Sayings of Jesus (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1983).

- Buchanan = George Wesley Buchanan, The Gospel of Matthew (2 vols.; MBC; Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen, 1996).

- Bultmann = Rudolf Bultmann, The History of the Synoptic Tradition (trans. John Marsh [Die Geschichte der synoptischen Tradition, 1921]; New York: Harper & Row, 1963).

- Bundy = Walter E. Bundy, Jesus and the First Three Gospels (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1955).

- Cadbury, Style = Henry J. Cadbury, The Style and Literary Method of Luke (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1920; repr., New York: Kraus, 1969).

- Cadbury, Making = __________, The Making of Luke-Acts (London: SPCK, 1927; repr., Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1999).

- Catchpole = David R. Catchpole, The Quest for Q (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1993).

- Collins = Adela Yarbro Collins, Mark: A Commentary (Hermeneia; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2007).

- Conzelmann = Hans Conzelmann, The Theology of St. Luke (trans. Geoffrey Buswell [Die Mitte Der Zeit, 1954]; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1961).

- Creed = John Martin Creed, The Gospel according to St. Luke: The Greek Text with Introduction, Notes, and Indices (London: MacMillan, 1930).

- Crook = Zeba Crook, Parallel Gospels: A Synopsis of Early Christian Writing (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Culpepper = R. Alan Culpepper, Matthew: A Commentary (New Testament Library; Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2022).*

- Dalman = Gustaf H. Dalman, The Words of Jesus Considered in the Light of Post-Biblical Jewish Writings and the Aramaic Language: I. Introduction and Fundamental Ideas (trans. D. M. Kay [Die Worte Jesu, 1898]; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1902).

- Daube = David Daube, The New Testament and Rabbinic Judaism (London: University of London, Athlone, 1956).

- Davies-Allison = W. D. Davies and Dale C. Allison, Jr., A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew (3 vols.; ICC; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1988, 1991, 1997).

- Delitzsch = Franz Julius Delitzsch, Hebrew New Testament (11th ed.; British and Foreign Bible Society, 1891).

- Dibelius = Martin Dibelius, From Tradition to Gospel (trans. Bertram Lee Woolf; New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1935).

- Dos Santos = Elmar Camillo Dos Santos, An Expanded Hebrew Index for the Hatch-Redpath Concordance to the Septuagint (Jerusalem: Dugith, 1976).

- Edersheim = Alfred Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah (2 vols.; London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1883; repr. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1993).

- Edwards = James R. Edwards, The Gospel Accroding to Luke (PNTG; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015).

- Evans = Craig A. Evans, Mark 8:27-16:20 (WBC 34B; Dallas: Word Books, 2001).

- Even-Shoshan, Millon = Avraham Even-shoshan, Ha-Millon He-Hadash (Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer, 1966) (Hebrew).

- Even-Shoshan, Concordance = Avraham Even-Shoshan, ed., A New Concordance of the Bible (Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer, 1989).

- Fitzmyer = Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke (AB 28A and 28B; Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1981, 1985).

- Fleddermann = Harry T. Fleddermann, Q: A Reconstruction and Commentary (Leuven: Peeters, 2005).

- Flusser, Jesus = David Flusser, Jesus (3d ed.; Jerusalem: Magnes, 2001).

- Flusser, JOC = __________, Judaism and the Origins of Christianity (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1988).

- Flusser, JSTP1 = __________, Judaism of the Second Temple Period: Volume 1, Qumran and Apocalypticism (Grand Rapids and Jerusalem: Eerdmans, Jerusalem Perspective and Magnes Press, 2007).

- Flusser, JSTP2 = __________, Judaism of the Second Temple Period: Volume 2, Sages and Literature (Grand Rapids and Jerusalem: Eerdmans, Jerusalem Perspective and Magnes Press, 2009).

- Flusser, Sage = __________, The Sage from Galilee: Rediscovering Jesus’ Genius (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007).

- Foakes Jackson-Lake = The Beginnings of Christianity, Part I: The Acts of the Apostles (ed. F. J. Foakes Jackson and Kirsopp Lake; 5 vols.; London: Macmillan, 1920–33).

- France, Mark = R. T. France, The Gospel of Mark: A Commentary on the Greek Text (NIGTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002).

- France, Matt. = __________, The Gospel of Matthew (NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007).

- Fredriksen, From Jesus = Paula Fredriksen, From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988).

- Funk-Hoover = Robert W. Funk, Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar, The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus (New York: Macmillan, 1993).

- Geldenhuys = Norval Geldenhuys, The Gospel of Luke (NICNT; Grand Raptids: Eerdmans, 1951, repr. 1983).‡

- Gesenius = W. Gesenius, Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar (ed. E. Kautzsch; trans. A. E. Cowley; 2d ed.; Oxford: Clarendon, 1910).

- Gill = John Gill, Exposition of the Old and New Testaments (1746-1766) (9 vols.; London: Matthews & Leigh, 1809; repr., Paris, Ark.: Baptist Standard Bearer, 1989).

- Ginzberg = Louis Ginzberg, Legends of the Jews (2 vols.; 2d ed.; trans. Henrietta Szold and Paul Radin; Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2003).

- Gould = Ezra P. Gould, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to St. Mark (ICC; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1896).

- H. B. Green = H. Benedict Green, The Gospel According to Matthew in the Revised Standard Version: Introduction and Commentary (NCB; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975).

- J. Green = Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke (NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997).

- Guelich = Robert A. Guelich, Mark 1-8:26 (WBC 34A; Dallas: Word Books, 1989).

- Gundry, Mark = Robert H. Gundry, Mark: A Commentary on His Apology for the Cross (2 vols.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993).

- Gundry, Matt. =__________, Matthew: A Commentary on His Literary and Theological Art (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982).*

- Gundry, Use = __________, The Use of the Old Testament in St. Matthew’s Gospel With Special Reference to the Messianic Hope (Leiden: Brill, 1967).

- Haenchen = Ernst Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles: A Commentary (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1971).

- Hagner = Donald A. Hagner, Matthew (WBC 33A-33B; Dallas: Word Books, 1993, 1995).

- HALOT = Ludwig Koehler and Walter Baumgartner, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (trans. M. E. J. Richardson; electronic version by OakTree Software; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 2000).

- Harnack = Adolf von Harnack, The Sayings of Jesus: The Second Source of St. Matthew and St. Luke (trans. J. R. Wilkinson [Sprüche und Reden Jesu: die Zweite Quelle des Matthäus und Lukas, 1907]; New York: Putnam, 1908; repr., Eugene, Oreg.: Wipf and Stock, 2004).

- Hatch-Redpath = Edwin Hatch and Henry A. Redpath, A Concordance to the Septuagint and the Other Greek Versions of the Old Testament (Including the Apocryphal Books) (3 vols.; Oxford: Clarendon, 1897; repr., 2 vols.; Grand Rapids: Baker, 1983).

- Hawkins = John C. Hawkins, Horae Synopticae (2d ed.; Oxford: Clarendon, 1909).

- Hooker = Morna D. Hooker, The Gospel According to Saint Mark (Blacks New Testament Commentaries; London: A & C Black, 1991; repr. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1997).

- Huck = Albert Huck, Synopsis of the First Three Gospels (9th ed. rev. by Hans Lietzmann; English ed. by F. L. Cross; Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1959).

- Hurvitz = Avi Hurvitz, A Concise Lexicon of Late Biblical Hebrew: Linguistic Innovations in the Writings of the Second Temple Period (VTS 160; Leiden: Brill, 2014).

- JANT = Amy-Jill Levine and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds., The Jewish Annotated New Testament (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Jastrow = Marcus Jastrow, A Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature (2d ed.; New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1903; repr., Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2005).

- JE = Isidore Singer, ed., Jewish Encyclopedia (12 vols.; New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1901-1906).

- Jeremias, Parables = Joachim Jeremias, The Parables of Jesus (rev. ed.; trans. S. H. Hooke [Die Gleichnisse Jesu, 1947]; New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1963).

- Jeremias, Prayers = __________, The Prayers of Jesus (trans. C. Burchard and J. Reumann; London: SCM, 1967).

- Jeremias, Theology = __________, New Testament Theology: The Proclamation of Jesus (John Bowden trans. [Neutestamentliche Theologie, 1. Die Verkündigung Jesu, 1971]; New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1971).

- Jeremias, Sprache = __________, Die Sprache des Lukasevangeliums: Redaktion und Tradition im Nicht-Markusstof des dritten Evangeliums (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1980).

- Joüon-Muraoka = Paul Joüon and T. Muraoka, A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew (2 vols.; Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1996).

- JS1 = R. Steven Notley, Marc Turnage, and Brian Becker, eds., Jesus’ Last Week: Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels 1 (JCP 11; Leiden: Brill, 2006).

- JS2 = Randall Buth and R. Steven Notley, eds., The Language Environment of First-century Judaea: Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels 2 (JCP 26; Leiden: Brill, 2014).

- Kazen = Thomas Kazen, Jesus and Purity Halakhah: Was Jesus Indifferent to Impurity? (rev. ed.; Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2010).

- Keener = Craig S. Keener, A Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999).

- Kilpatrick = G. D. Kilpatrick, The Origins of the Gospel According to St. Matthew (Oxford: Clarendon, 1946).

- Klausner = Joseph Klausner, Jesus of Nazareth: His Life, Times, and Teaching (trans. Herbert Danby; New York: MacMillan, 1925).

- Kloppenborg = John S. Kloppenborg, The Formation of Q: Trajectories in Ancient Wisdom Collections (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987; repr. Harrisburg: Trinity Press International, 1999).

- Knox = Wilfred L. Knox, The Sources of the Synoptic Gospels (2 vols.; ed. H. Chadwick; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953-1957).

- Kutscher = Eduard Yechezkel Kutscher, A History of the Hebrew Language (ed. Raphael Kutscher; 2d ed.; Jerusalem: Magnes; Leiden: Brill, 1984).

- Lachs = Samuel Tobias Lachs, A Rabbinic Commentary on the New Testament: The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke (Hoboken, N.J.: Ktav, 1987).

- Lane = William L. Lane, The Gospel According to Mark: The English Text with Introduction, Exposition and Notes (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974).†

- LHNC = Robert Lindsey’s handwritten notes in the margins of his copy of William F. Moulton and Alfred S. Geden, eds., A Concordance to the Greek Testament According to the Texts of Westcott and Hort, Tischendorf, and the English Revisers (3d ed.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1926).

- LHNS = Robert Lindsey’s handwritten notes in the margins of his copy of Albert Huck, Synopsis of the First Three Gospels (9th ed. rev. by Hans Lietzmann; English ed. by Frank Leslie Cross; New York: American Bible Society, 1936).[45]

- Lightfoot = John Lightfoot, A Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica: Matthew-1 Corinthians (London: Oxford University Press, 1859; repr., 4 vols; Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1989 [orig. pub. as Horae Hebraicae et Talmudicae, 1658-1674]).**

- Lindsey, GCSG = Robert L. Lindsey, ed., A Comparative Greek Concordance of the Synoptic Gospels (3 vols.; Jerusalem: Dugith, 1985, 1988, 1989).

- Lindsey, HTGM = __________, A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark (2d ed.; Jerusalem: Dugith, 1973).

- Lindsey, JRL = __________, Jesus Rabbi & Lord: The Hebrew Story of Jesus Behind Our Gospels (Oak Creek, Wisc.: Cornerstone, 1990); Second edition, 2009, with emendations and updates, Jesus, Rabbi and Lord: A Lifetime’s Search for the Meaning of Jesus’ Words.

- Lindsey, TJS = __________, The Jesus Sources.

- Loos, Miracles = H. van der Loos, The Miracles of Jesus (Leiden: Brill, 1965).*

- LSJ = Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, and Henry Stuart Jones, A Greek-English Lexicon (9th ed.; Oxford: Clarendon, 1968).

- Luz = Ulrich Luz, Matthew: Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (3 vols.; trans. James E. Crouch [Das Evangelium nach Matthäus, 1985-2002]; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2001, 2005, 2007).

- Mann = C. S. Mann, Mark (AB 27; Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1986).

- Manson, Sayings = Thomas Walter Manson, The Sayings of Jesus as Recorded in the Gospels According to St. Matthew and St. Luke (London: SCM Press, 1957; repr., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979 [orig. pub. 1937]).

- Manson, Teaching = Thomas Walter Manson, The Teaching of Jesus: Studies of Its Form and Content (2d ed.; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959 [orig. pub. 1935]).

- Manson, Luke = William Manson, The Gospel of Luke (MNTC; London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1930).

- Marcus = Joel Marcus, Mark (2 vols.; AB 27; Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 2000; AB 27A; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009).

- Marshall = I. Howard Marshall, The Gospel of Luke: A Commentary on the Greek Text (NIGTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1978).

- Martin, Syntax 1 = Raymond Martin, Syntax Criticism of the Synoptic Gospels (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen, 1987).

- Martin, Syntax 2 = __________, Syntax Criticism of Johannine Literature, The Catholic Epistles, and the Four Gospel Passion Accounts (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen, 1989).

- McNeile = Alan Hugh McNeile, The Gospel According to St. Matthew (London: Macmillan, 1915).

- Meier, Marginal = John P. Meier, A Marginal Jew (5 vols.; New York: Doubleday, 1991-2016).*[46]

- Metzger = Bruce M. Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (London and New York: United Bible Societies, 1975).‡

- Milligan = George Milligan, Selections from the Greek Papyri (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1910; repr. 1912).

- Montefiore, RLGT = Claude G. Montefiore, Rabbinic Literature and Gospel Teachings (London: Macmillan, 1930).

- Montefiore, TSG = __________, The Synoptic Gospels (2 vols.; 2d ed.; London: Macmillan, 1927).

- Moule, Idiom = Charles F. D. Moule, An Idiom Book of New Testament Greek (2d ed.; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959).

- Moule, Birth = __________, The Birth of the New Testament (New York: Harper & Row, 1962).

- Moulton = James Hope Moulton, A Grammar of New Testament Greek; Vol. 1 (2d ed.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1906).

- Moulton-Geden = W. F. Moulton and A. S. Geden, A Concordance to the Greek Testament According to the Texts of Westcott and Hort, Tischendorf, and the English Revisers (4th ed.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1963 [repr. 1974]).

- Moulton-Howard = James Hope Moulton and Wilbert Francis Howard, A Grammar of New Testament Greek; Vol. 2 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1929).

- Moulton-Milligan = James Hope Moulton and George Milligan, The Vocabulary of the Greek Testament Illustrated from the Papyri and other Non-Literary Sources (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1930; repr. 1976).

- Muraoka, Lexicon = Takamitsu Muraoka, A Greek-English Lexicon of the Septuagint (Louvain: Peeters, 2009).

- Muraoka, Syntax = __________, A Syntax of Septuagint Greek (Leuven: Peeters, 2016).*

- Nolland, Luke = John Nolland, Luke (WBC 35A-35C; Dallas: Word Books, 1989, 1993, 1993).

- Nolland, Matt. = __________, The Gospel of Matthew: A Commentary on the Greek Text (NIGTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005).

- Notley-Safrai = R. Steven Notley and Ze’ev Safrai, Parables of the Sages: Jewish Wisdom from Jesus to Rav Ashi (Jerusalem: Carta, 2011).

- OHJDL = Catherine Hezser, ed., Oxford Handbook of Jewish Daily Life in Roman Palestine (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).*

- Plummer, Luke = Alfred Plummer, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to St. Luke (ICC; 5th ed.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1922 [orig. pub. 1896]).

- Plummer, Mark = __________, The Gospel According to St. Mark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1914).

- Plummer, Matt. = Alfred Plummer, An Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to S. Matthew (London: Elliot Stock, 1909).

- Pryke = E. J. Pryke, Redactional Style in the Marcan Gospel: A Study of Syntax and Vocabulary as guides to Redaction in Mark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978).

- Rahmani = L. Y. Rahmani, A Catalogue of Jewish Ossuaries in the Collections of the State of Israel (Jerusalem: The Israel Antiquities Authority and The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994).**

- Rainey-Notley = Anson F. Rainey and R. Steven Notley, The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006).

- Resch = Alfred Resch, Die Logia Jesu: nach dem griechischen und hebräischen Text wiederhergestellt (Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs, 1898).

- Robinson-Hoffmann-Kloppenborg = James M. Robinson, Paul Hoffmann and John S. Kloppenborg, eds., The Critical Edition of Q (Hermeneia; Leuven: Peeters; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2000).

- Safrai-Safrai = Shmuel Safrai and Ze’ev Safrai, Haggadah of the Sages (trans. Miriam Schlüsselberg; Jerusalem: Carta, 2009).

- Safrai-Stern = Shmuel Safrai and Menahem Stern, eds., The Jewish People in the First Century (2 vols.; CRINT I.1-2; Amsterdam: Van Gorcum; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1976) (vol. 1 and vol. 2 on the Internet Archive).

- Sandt-Flusser = Huub van de Sandt and David Flusser, The Didache: Its Jewish Sources and its Place in Early Judaism and Christianity (CRINT III.5; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002).

- Schürer = Emil Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (175 B.C.-A.D. 135) (ed. Geza Vermes, Fergus Millar and Matthew Black; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1979).

- Schweizer = Eduard Schweizer, The Good News According to Matthew (trans. David E. Green; Atlanta: John Knox, 1975).

- Segal = Moses H. Segal, A Grammar of Mishnaic Hebrew (Oxford: Clarendon, 1927).

- Smith = Morton Smith, Tannaitic Parallels to the Gospels (JBL Monograph Series VI; Society of Biblical Literature, 1951; repr. 1968).

- Snodgrass = Klyne R. Snodgrass, Stories with Intent: A Comprehensive Guide to the Parables of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008).

- Sokoloff = Michael Sokoloff, A Dictionary of Jewish Palestinian Aramaic of the Byzantine Period (2d ed.; Ramat-Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2002).

- Stern = Menahem Stern, Greek and Latin Authors on Jews and Judaism (3 vols.; Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1974, 1980, 1984).

- Strack-Billerbeck = Hermann L. Strack and Paul Billerbeck, Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud und Midrasch (4 vols.; Munich: Beck, 1922-1928).

- Strecker = Georg Strecker, The Sermon on the Mount: An Exegetical Commentary (trans. O. C. Dean, Jr. [Die Bergpredigt, 1985]; Nashville: Abingdon, 1988).

- Streeter = Burnett Hillman Streeter, The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins (2d ed.; London: Macmillan, 1930).

- Swete = Henry Barclay Swete, The Gospel According to St. Mark (3d rev. ed.; London: Macmillan, 1913 [orig. pub. 1898]).

- Taylor = Vincent Taylor, The Gospel According to St. Mark (2d ed.; London: Macmillan, 1966 [orig. pub. 1952]).

- TDNT = Gerhard Kittel and Gerhard Friedrich, eds., Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (trans. Geoffrey W. Bromiley; 10 vols.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1964-1976).[47]

- TDOT = G. Johannes Botterweck et al. eds., Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament (15 vols.; trans. John T. Willis et al.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974-2006).

- Thackeray = Henry St James Thackeray, A Grammar of the Old Testament in Greek According to the Septuagint (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1909).

- Theissen, Gospels = Gerd Theissen, The Gospels in Context: Social and Political History in the Synoptic Tradition (trans. Linda M. Maloney; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1991).

- Theissen, Miracle Stories = __________, The Miracle Stories of the Early Christian Tradition (trans. Francis McDonagh [Urchristliche Wundergeschichten, 1974]; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983).*

- Theissen, Social = __________, Social Reality and the Early Christians: Theology, Ethics, and the World of the New Testament (trans. Margaret Kohl; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992).*

- Tomson, If This Be = Peter J. Tomson, ‘If this be from Heaven…’ Jesus and the New Testament Authors in their Relationship to Judaism (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001).

- Tristram = H. B. Tristram, The Natural History of the Bible (9th ed.; London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1898 [1867]).*

- Trommii = Abrahami Trommii, Concordantiæ Græcæ Versionis Vulgo Dictæ Septuaginta Interpretum (2 vols.; Amsterdam, 1718) [Α-Λ, Μ-Ω].

- Turner = C. H. Turner, The Gospel According to St. Mark (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1931).

- Vermes, Jew = Geza Vermes, Jesus the Jew: A Historian’s Reading of the Gospels (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1981).

- Vermes, Religion = __________, The Religion of Jesus the Jew (London: SCM Press, 1993).

- Vermes, Authentic = __________, The Authentic Gospel of Jesus (London: Penguin, 2003).

- Wolter = Michael Wolter, The Gospel According to Luke (2 vols.; trans. Wayne Coppins and Christoph Heilig; Waco, Tex.: Baylor, 2016-2017).

- Witherington = Ben Witherington III, Matthew (SHBC; Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 2006).

- Young, JHJP = Brad H. Young, Jesus and His Jewish Parables: Rediscovering the Roots of Jesus’ Teaching (Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist, 1989).

- Young, JJT = __________, Jesus the Jewish Theologian (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1995).

- Young, MTR = __________, Meet the Rabbis: Rabbinic Thought and the Teachings of Jesus (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2007).

- Young, Parables = __________, The Parables: Jewish Tradition and Christian Interpretation (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1998).

- Zimmermann = Frank Zimmermann, The Aramaic Origin of the Four Gospels (New York: Ktav, 1979).

- Zohary = Michael Zohary, Plants of the Bible (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

* A single asterisk indicates that our copy of the book was purchased with a generous gift from Pieter Lechner.

** A double asterisk indicates that our copy of the book was purchased with a generous gift from Gary and Pearl Asperschlager.

† A dagger indicates that our copy came from the personal library of Rev. Wayne L. Sawyer.

‡ A double dagger indicates that our copy came from the personal library of Rev. Robert Cloutier.

Click here to view a Transliteration Guide to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction.

Click here to view the Scripture Key to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua (comparable to LOY’s Table of Contents).

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

- [1] The original version of this introduction was revised with the assistance of Joshua N. Tilton and Lauren S. Asperschlager. ↩