How to cite this article:

Joshua N. Tilton and David N. Bivin, “Teaching in Kefar Nahum,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2023) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/27447/].

Matt. 4:13-16; 7:28-29; Mark 1:21-28;

Luke 4:31-37[1]

וַיֵּלֶךְ אֶל כְּפַר נַחוּם עִיר הַגָּלִיל וְהָיָה מְלַמֵּד אֹתָם בַּשַּׁבָּתוֹת וּבְבֵית הַכְּנֶסֶת הָיָה אָדָם אֲשֶׁר רוּחַ הַטֻּמְאָה בּוֹ וַיִּזְעַק קוֹל גָּדוֹל הָא מַה לָּנוּ וָלָךְ יֵשׁוּעַ אִישׁ נָצְרָה בָּאתָ לְאַבֵּד אֹתָנוּ יְדַעְתִּיךָ מָה אַתָּה ***קְדוֹשׁ אֱלֹהִים*** [קִלְלַת אֱלֹהִים] וַיִּגְעַר בָּהּ יֵשׁוּעַ לֵאמֹר שִׁתְקִי צְאִי מִמֶּנּוּ וַיַּשְׁלִכֵהוּ הַשֵּׁד אֶל תּוֹכָם וַיֵּצֵא מִמֶּנּוּ וְלֹא הִזִּיקוֹ וַיְהִי פַּחַד עַל כֻּלָּם וַיְדַבְּרוּ אִישׁ אֶל רֵעֵהוּ לֵאמֹר מָה הַדָּבָר הַזֶּה שֶׁבְּרָשׁוּת וּבְעֹז הוּא מְצַוֶּה לְרוּחוֹת הַטֻּמְאָה וְהֵן יוֹצְאוֹת וַיֵּצֵא הַדָּבָר בְּכָל מָקוֹם

Yeshua went to Kefar Nahum, a city of the Galilee, and taught them every Sabbath.

Now in the synagogue was a man who had an impure spirit in him. And he cried out in a loud voice, “So then, Yeshua, man of Natzerah, what have you to do with us, the people of Kefar Nahum? I think you’ve come here to ruin our community! I know what you really are! You are an embarrassment to God!”

Then Yeshua rebuked the impure spirit, saying, “Be silent! Come out of him!” And the demon flung the man it had possessed into their midst as it came out of him. Nevertheless, it did him no harm.

Awe came over the people assembled in the synagogue. And they spoke to each other, saying, “What have we just witnessed? This man Yeshua issues authoritative and powerful commands to impure spirits and they come out of people we didn’t even know were possessed!” And word of this event spread everywhere.[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Teaching in Kefar Nahum click on the link below:

Story Placement

Teaching in Kefar Nahum appears in the Gospels of Luke and Mark, and although Matthew’s Gospel does not record the story of Jesus’ experience in Capernaum’s synagogue, Teaching in Kefar Nahum has also left its impression on Matthew’s Gospel.

In Luke’s Gospel Teaching in Kefar Nahum (Luke 4:31-37) follows the account of Jesus’ visit to his hometown in Nazareth (Nazarene Synagogue; Luke 4:14-30). This story order is distinctly odd, since in Nazarene Synagogue Jesus mentions having performed miracles in Capernaum (Luke 4:23), even though Luke had not yet recorded either a miracle or a visit to Capernaum. Because of Jesus’ remark in Luke 4:23, the author of Luke would have done better if he had made Nazarene Synagogue the sequel to Teaching in Kefar Nahum rather than its prequel. But there is evidence to suggest that the author of Luke did not invent his story order and that, in fact, it was not especially to his liking.

The evidence that the author of Luke based his story order on a source comes from Matthew’s Gospel, for Matthew, unlike Mark, knows of a sequence in which Jesus, having returned to the Galilee after his temptation, goes first to Nazareth and then to Capernaum (Matt. 4:12-13). Not only do Luke and Matthew agree on the order of Jesus’ movements, they also refer to Nazareth using the distinctive form Ναζαρά (Nazara [Matt. 4:13; Luke 4:16]), a form that does not appear elsewhere in the Synoptic Gospels. Since it boggles the mind to suppose that the authors of Luke and Matthew independently created the sequence Galilee→Nazareth→Capernaum and that their sole uses of the distinct form Ναζαρά in this independently invented sequence is a mere coincidence, we believe that the authors of Luke and Matthew inherited the sequence Galilee→Nazareth→Capernaum and the unique form Ναζαρά from their shared non-Markan source (see below, Comment to L1).

The evidence that the author of Luke was not enamored with the story order he inherited from his source (Return to the Galil→Nazarene Synagogue→Teaching in Kefar Nahum) comes from the redactional changes the author of Luke made to the pericopae on either side of Nazarene Synagogue. These redactional changes emphasize the positive response Jesus’ teaching elicited from his hearers (Luke 4:15, 32), a response that contrasts with the negative reaction to Jesus’ teaching in Nazareth.[3] The author of Luke’s redactional emphasis on the favorable impression Jesus’ teaching made on his listeners appears, therefore, to be an attempt at neutralizing the effect Nazarene Synagogue might have on Luke’s readers. Since Nazarene Synagogue is the first story in Luke’s Gospel in which Jesus appears in a synagogue, and since in that story the congregation responded negatively to Jesus’ teaching, the author of Luke feared that his readers would infer that Jesus’ contemporaries generally rejected Jesus’ teaching. In order to prevent his readers from drawing this inference, the author of Luke surrounded Nazarene Synagogue with reports of favorable responses to Jesus’ teaching. The fact that the author of Luke felt the need to thus surround Nazarene Synagogue with laudatory remarks concerning Jesus’ teaching ability suggests that the author of Luke felt constrained to preserve the pericope order he found in his source even though it did not serve his apologetic purpose. In any event, we believe Luke’s awkward placement of Teaching in Kefar Nahum after Nazarene Synagogue reflects the order of Luke’s non-Markan source, not the author of Luke’s lack of literary skill.

Viewed from the perspective of Lindsey’s hypothesis, Mark’s omission of Nazarene Synagogue from Luke’s Return to the Galil→Nazarene Synagogue→Teaching in Kefar Nahum sequence is a literary and logical improvement. Noting that in Luke 4:23 Jesus mentions miracles he had performed in Capernaum, the author of Mark put off his version of Nazarene Synagogue until he had reported several of Jesus’ miraculous deeds and made Capernaum the location of some of them.[4] Into the slot Nazarene Synagogue vacated, the author of Mark inserted his version of Yeshua Calls His First Disciples (Mark 1:16-20). Thus the call of the first disciples, which in Luke takes place after the Sabbath on which Jesus taught in the synagogue and exorcised the demon from the community, takes place in Mark prior to these events.[5]

In Matthew’s Gospel Teaching in Kefar Nahum seems to be missing, but in fact the author of Matthew has simply repurposed it. Teaching in Kefar Nahum lies just below the surface of Matthew’s narrative structure, and at the few places where it breaks through the surface it remains recognizable. We have already mentioned the first place where Teaching in Kefar Nahum breaks through the surface of Matthew’s narrative. It occurs in Matthew’s version of Return to the Galil, where Matthew, unlike Mark, but in agreement with Luke, refers to Jesus’ transition from Nazareth to Capernaum (Matt. 4:13).[6] By locating Capernaum in the tribal allotment of Zebulun and Naphtali (see below, Comment to L3), the author of Matthew took the opportunity afforded by this reference to Capernaum to claim that Jesus’ movements in the Galilee fulfilled prophecy (Matt. 4:14-16). The second place where Teaching in Kefar Nahum surfaces in Matthew’s Gospel is at the end of the Sermon on the Mount, where the crowds respond to Jesus’ authoritative teaching (Matt. 7:28b-29). Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount appears in exactly the same slot where Teaching in Kefar Nahum appears in Mark.[7] In Teaching in Kefar Nahum the congregants praise Jesus for his teaching ability even though Mark’s readers learn nothing of the content or even subject matter of Jesus’ teaching.[8] The author of Matthew corrected this deficiency by having Jesus deliver the Sermon on the Mount,[9] but because he did not consider the Capernaum synagogue to be a suitable location for this most monumental of sermons, the author of Matthew moved the location of Jesus’ preaching from the synagogue to a mountaintop. Nevertheless, the audience’s assessment of Jesus’ teaching in the Sermon on the Mount in Matt. 7:28b-29 echoes that of the congregants in Capernaum in Mark 1:22.[10]

There is a third place where Teaching in Kefar Nahum crops up in Matthew’s narrative structure, but this time without quite breaking through the surface. There was nothing to prevent the author of Matthew from returning to Mark’s pericope order after having replaced Teaching in Kefar Nahum with the Sermon on the Mount, but he did not do so. But neither did the author of Matthew adopt the order of his non-Markan source for the Sermon on the Mount (i.e., the Anthology [Anth.]), in which Jesus’ sermon was followed by Centurion’s Slave.[11] Instead, the author of Matthew did something far more subtle. Bypassing Shimon’s Mother-in-Law, Healings and Exorcisms and A Deserted Place, the author of Matthew picked up Mark’s narrative at Man with Scale Disease, which in Mark follows a notice that Jesus went preaching in the synagogues in all the Galilee and expelling demons (Mark 1:39). Teaching in Kefar Nahum is a concrete example of the activity Mark 1:39 describes, so it can be no accident that, having skipped the story of the exorcism Jesus performed in Capernaum’s synagogue, the author of Matthew resumed Mark’s narrative with Man with Scale Disease, right after this Markan summary.

The author of Matthew did not follow Mark’s story order for long, however. After returning to Mark’s sequence for Man with Scale Disease, Matthew once again parts ways with his Markan source. Where Mark has Jesus enter Capernaum for Bedridden Man (Mark 2:1), Matthew has Jesus enter Capernaum for Centurion’s Slave (Matt. 8:5), which, as we noted, followed Jesus’ sermon in Anth. Having brought Jesus into Capernaum, the author of Matthew was now able to take up Shimon’s Mother-in-Law and Healings and Exorcisms, two stories that in Mark are set in Capernaum and which the author of Matthew had previously bypassed.

From all we have observed above, it appears that none of the Synoptic Gospels, nor even Anth., preserves Teaching in Kefar Nahum at the point it appeared in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua. Nevertheless, internal evidence suggests that Luke and Anth. were correct in placing Teaching in Kefar Nahum prior to the calling of Jesus’ earliest disciples, since the disciples play no role in either the Lukan or Markan versions of the pericope. We have therefore placed Teaching in Kefar Nahum in the section of the reconstructed Hebrew Life of Yeshua entitled “Yeshua, the Galilean Miracle-Worker.” In this section Jesus taught and performed miraculous healings, but as yet had no full-time disciples.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum consists of two parts that parallel one another but do not actually intersect. In Part One (Luke 4:31-32) Jesus habitually teaches in Capernaum on the Sabbath and the people wonder at his teaching because Jesus’ word had authority. In Part Two (Luke 4:33-37) Jesus attends the local synagogue and is accosted by a demon-possessed individual. Jesus exorcises the demon and the congregants wonder at Jesus’ authority over the impure spirits. While the two stories mirror one another, the differences must not be overlooked. Part One describes a general state of affairs, whereas Part Two describes a specific incident. Part One takes place in Capernaum, while Part Two takes place in the synagogue. Part One is entirely narrated, but Part Two portrays “live” action. For this reason some scholars regard Part One as merely the narrative introduction of the pericope, but this ignores the independence of the two parts of Luke’s narrative. If Luke’s Part Two had been omitted, no one would have supposed that anything was missing. The positive response to Jesus’ teaching in Part One is not required for Luke’s Part Two to make sense.

|

Part One (Luke 4:31-32) |

Part Two (Luke 4:33-37) |

|

And he went down to Capernaum, a city of the Galilee. |

|

|

And he was teaching them on the Sabbaths. |

And in the synagogue was a man having the spirit of an impure demon. |

|

And he cried out in a loud voice, “Yikes! What is there for us and for you, Jesus of Nazara? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are—the Holy One of God!” |

|

|

And Jesus rebuked it, saying, “Be silenced and come out of him!” And throwing him into the middle, the demon went out of him, but did not harm him. |

|

|

And they were astonished at his teaching |

And dread came upon everyone and they spoke to one another saying, |

|

because his word was with authority. |

“What is this thing, that in authority and power he commands the impure spirits and they go out?” |

|

And the report about him went out into every place of the surrounding region. |

Despite being parallel, Parts One and Two of Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum are clearly unbalanced. Part One is a mere shadow of Part Two, a bland description compared to Part Two’s dramatic action and vivid details.

Mark’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum also falls into two parts,[12] but the two parts are more closely united than in Luke’s version. Both parts of Mark’s version take place in Capernaum’s synagogue (L19, L36),[13] both parts highlight Jesus’ teaching (L30, L65), and both parts emphasize Jesus’ personal authority (L31, L66), whereas in Luke Jesus’ personal authority is mentioned only in Part Two (L66); Luke’s Part One refers to the authority of Jesus’ word (L31), not the authority of Jesus’ person. Moreover, the two parts of Mark’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum take place on a single Sabbath, whereas in Luke Part One takes place over a series of Sabbaths, while Part Two occurs on a single Sabbath.[14] Viewed from the perspective of Lindsey’s hypothesis, it appears that the author of Mark took considerable trouble to more fully integrate Parts One and Two of the narrative he found in Luke’s Gospel. Since it is difficult to believe that the author of Luke would have attempted to divorce the teaching section of the narrative from the exorcism section, transmission from Luke to Mark is more credible than a Mark to Luke progression.

In our discussion of how Teaching in Kefar Nahum surfaces at various points early in Matthew’s Gospel we demonstrated the author of Matthew’s secondary use of this pericope. It is also clear that it was the Markan form of Teaching in Kefar Nahum that the author of Matthew knew, since he quoted the statement that Jesus “taught as one having authority and not as the scribes,” which occurs in Mark’s version of the pericope but not in Luke’s.

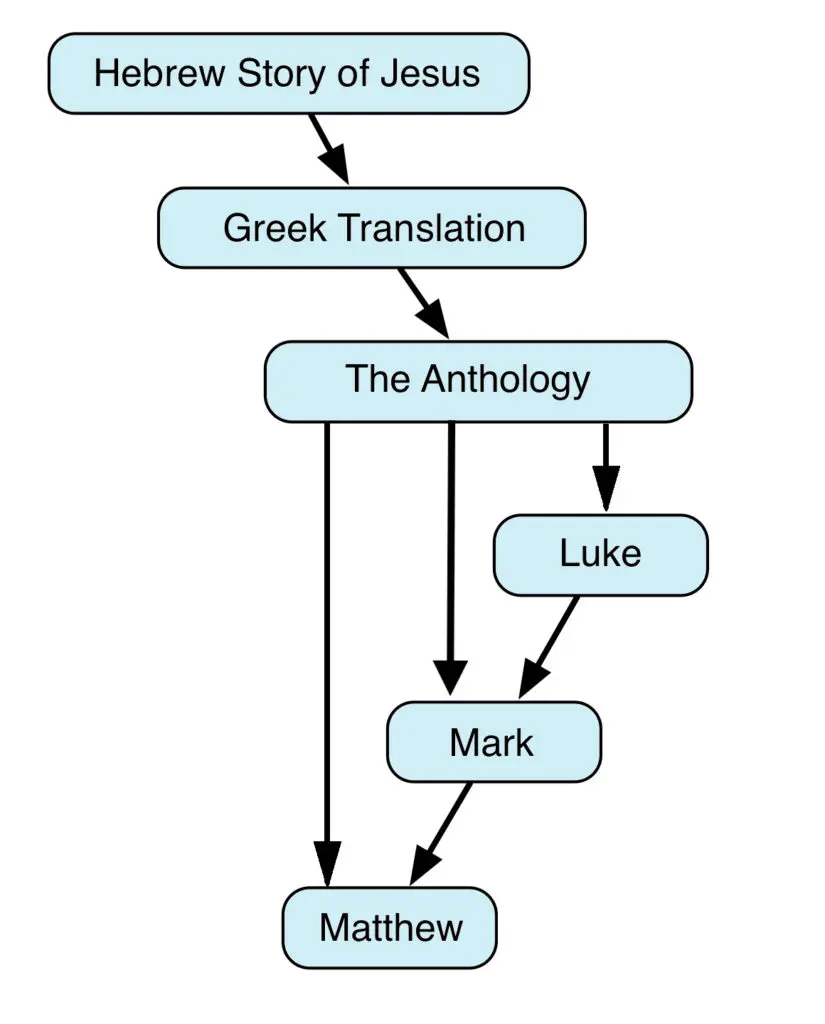

Thus, with respect to Teaching in Kefar Nahum, it is possible to establish a clear progression from Luke to Mark to Matthew. But what was Luke’s source for this pericope? Flusser believed that Teaching in Kefar Nahum passed through the hands of a pre-synoptic redactor before reaching the hands of the author of Luke.[15] In terms of Lindsey’s hypothesis this would mean that Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum is based on the First Reconstruction (FR), and, indeed, Lindsey attributed Luke’s version to that source.[16] On the other hand, parts of Luke’s Teaching in Kefar Nahum are highly Hebraic, a quality that indicates the Anthology (Anth.) as Luke’s source for this pericope. Also, we have found that Anth. was the source of Luke’s version of Yeshua’s Testing and Return to the Galil. In addition, the Lukan-Matthean agreement to refer to Jesus’ movement from Nazareth to Capernaum and the Lukan-Matthean agreement to use the rare form Ναζαρά in reference to Nazareth also suggest that Anth. may have been Luke’s source for Nazarene Synagogue. Since the author of Luke tended to stick with a source for large blocks of material instead of switching between sources from pericope to pericope, Luke’s reliance upon Anth. for these pericopae may be a clue that the author of Luke depended on Anth. for Teaching in Kefar Nahum too. Moreover, there is no reason why the redactional activity, which is clearly present in Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum, must be attributed to the First Reconstructor and not to the author of Luke himself. On the contrary, Teaching in Kefar Nahum contains features of specifically Lukan redaction that appear in both Anth. and FR pericopae.[17] Since the most conspicuous redactional activity in Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum reflects the specifically Lukan concern to neutralize the bad impression of Jesus’ teaching ability Nazarene Synagogue might give to readers of Luke’s Gospel, very little of the redactional activity that can be detected in Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum remains that could be attributed to FR. It therefore seems best to trace Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum to Anth., and to attribute whatever redactional activity we encounter in Luke’s version of the pericope to the author of Luke himself.

Crucial Issues

- Where were the boundaries of Zebulun and Naphtali?

- In what way did Jesus contrast with the scribes?

- What was the cause of the people’s amazement?

- For whom did the demon speak: itself plus its host, its fellow demons, or the people of Capernaum?

- What is the meaning of “Nazarene”?

Comment

L1 καὶ καταλιπὼν τὴν Ναζαρὰ ἐλθὼν κατῴκησεν (Matt. 4:13). The statement that Jesus “forsook” Nazareth and took up residence in Capernaum is couched in Matthean vocabulary,[18] and the notion that Jesus made Capernaum his permanent base is not found in Mark or Luke.[19] Neither is Matthew’s wording in L1 especially Hebraic (the piling up of participles is more typical of Greek composition), so it is unlikely that in L1 Matthew reflects the text of Anth. Nevertheless, Jesus’ movement from Nazareth to Capernaum is paralleled in Luke, though not in Mark. Moreover, that Lukan parallel contains the only other instance of the form Ναζαρά (Nazara) in the Synoptic Gospels.[20] So even in this redactional verse the author of Matthew gleaned some of his information from a source.[21] We believe that source was none other than Luke’s source for Nazarene Synagogue (i.e., Anth.). The author of Matthew evidently preferred the Markan version of this pericope, perhaps because of its placement, which, as we noted, is less problematic than in the Anth. and Lukan versions. Despite his decision to record his version of Nazarene Synagogue in its Markan position, here in L1 the author of Matthew betrayed his knowledge of Anth.’s different arrangement.[22]

καὶ εἰσπορεύονται (Mark 1:21). There are several indications that Mark’s wording in L1 is redactional. First, the verb εἰσπορεύεσθαι (eisporevesthai, “to enter”) occurs with higher frequency in Mark (8xx) than in Matthew (1x) or Luke (5xx), and with almost no Lukan agreement.[23] Second, Mark’s verb is in the present tense, and the use of the historical present is typical of Markan redaction.[24] Third, the form of Mark’s verb is plural because it includes the disciples from the previous pericope (Mark 1:16-20). But since the disciples play no further role in Mark’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum, and no role at all in Luke’s version, the inclusion of the disciples in L1 by the use of a third-person plural verb is probably the author of Mark’s attempt to smooth the transition into a pericope in which the disciples originally played no part.[25]

καὶ κατῆλθεν (Luke 4:31). Luke’s statement that Jesus went down from Nazareth to Capernaum is topographically accurate[26] and belies the assertions of some scholars that the author of Luke was ignorant of the geography of the Holy Land.[27] Indeed, it may be that by his use of κατέρχεσθαι (katerchesthai, “to go down,” “to descend”) the author of Luke displayed his personal acquaintance with the Galilee, since this verb is typical of the writings of Luke.[28] The only reason to hesitate to attribute κατέρχεσθαι in L1 to Lukan redaction is the Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark to used a verb prefixed with κατ- (Matthew: κατοικεῖν; Luke: κατέρχεσθαι). However, since both verbs are likely to be redactional, the use of the κατ- prefix in Matt. 4:13 and Luke 4:31 is probably just coincidental.

Jesus’ Probable Route from Nazareth to Capernaum. Map from R. Steven Notley’s In the Master’s Steps: The Gospels in the Land (Jerusalem: Carta, 2014), 14.καὶ ἐπορεύθη (GR). Since none of the synoptic evangelists appear to have reproduced Anth.’s wording in L1, it is up to us to imagine how Anth. might have been worded. It may be assumed that the pericope would have opened with a verb such as “he came,” “he arrived at,” or the like. The phrase καὶ ἐπορεύθη (kai eporevthē, “and he went”) is as good a guess as any, resembling the opening of Widow’s Son in Nain: καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῷ ἑξῆς ἐπορεύθη εἰς πόλιν καλουμένην Ναῒν (“And it happened on the following day he went to a city called Nain”; Luke 7:11).

וַיֵּלֶךְ (HR). On reconstructing πορεύεσθαι (porevesthai, “to go”) with הָלַךְ (hālach, “walk,” “go”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L2.

L2 εἰς Καφαρναοὺμ (GR). All three synoptic evangelists have the phrase εἰς Καφαρναούμ (eis Kafarnaoum, “into Capernaum”) in L2, and there is no reason to doubt that Anth.’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum was similarly set in Capernaum. We have therefore accepted this phrase for GR.

אֶל כְּפַר נַחוּם (HR). On reconstructing Καφαρναούμ with כְּפַר נַחוּם (kefar naḥūm, “Capernaum”), see Woes on Three Villages, Comment to L17.

L3 πόλιν τῆς Γαλιλαίας (GR). Some scholars opine that the author of Luke added the description of Capernaum as “a city of the Galilee” for the benefit of his Gentile readers.[29] At any rate, the description is often thought to be redactional.[30] But even Jewish readers in Judea may not have been familiar with the village of Capernaum,[31] so there is no reason why πόλιν τῆς Γαλιλαίας (polin tēs Galilaias, “a city of the Galilee”) could not have come from Anth. It is typical of sources translated into Greek from Hebrew to refer even to small towns as “cities” due to the (misleading) equation of עִיר (‘ir, “rural settlement”) and πόλις (polis, “Hellenized urban center”). The omission of πόλιν τῆς Γαλιλαίας in Mark’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum is readily explained by the reference to Jesus’ walking beside the Sea of Galilee in Mark 1:16, so there was no need to reiterate Capernaum’s location in the Galilee in Mark 1:21.

עִיר הַגָּלִיל (HR). On reconstructing πόλις with עִיר, see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L2.

On reconstructing Γαλιλαία (Galilaia, “Galilee”) with גָּלִיל (gālil, “Galilee”), see A Voice Crying, Comment to L18.

τὴν παραθαλασσίαν ἐν ὁρίοις Ζαβουλὼν καὶ Νεφθαλείμ (Matt. 4:13). The author of Matthew replaced Anth.’s description of Capernaum as “a city of the Galilee” with the more detailed (not to say precise) reference to “Capernaum-by-the-Sea in the borders of Zebulun and Naphtali.” The phrase τὴν παραθαλασσίαν (tēn parathalassian, “the one by the sea”) may have been partly inspired by Mark’s reference to Jesus’ walking beside the Sea of Galilee (παρὰ τὴν θάλασσαν τῆς Γαλιλαίας [para tēn thalassan tēs Galilaias]) in Mark 1:16,[32] but, like “in the borders of Zebulun and Naphtali,” it is mainly in the service of the Isaiah quotation to follow.[33] Describing Capernaum as “by the sea” justifies the author of Matthew’s application of “way of the Sea” in Isa. 8:23 to Jesus’ move to Capernaum.

The author of Matthew certainly did not copy the phrase ἐν ὁρίοις Ζαβουλὼν καὶ Νεφθαλείμ (en horiois Zaboulōn kai Nefthaleim, “in the borders of Zebulun and Naphtali”) from Anth. It is purely a segue into the quotation of Isa. 8:23-9:1,[34] for without this phrase the scriptural quotation is irrelevant. But despite its being redactional, could the statement that Capernaum lay in the borders of Zebulun and Naphtali nevertheless be factually correct? The first problem with Matthew’s statement is that it situates Capernaum within the territories of two tribes, which cannot be accurate.[35] The second problem is that according to Josh. 19:10-16 Zebulun’s territory did not extend to the lake commonly referred to as the Sea of Galilee. According to Josh. 19:32-39, only the tribe of Naphtali inherited territory along the shore of the lake (cf. Deut. 33:23). Hence, according to one rabbinic tradition, the tribe of Naphtali had exclusive fishing rights on the Sea of Galilee (t. Bab. Kam. 8:18).

In order to save the author of Matthew from committing a geographical error, some scholars interpret ἐν ὁρίοις Ζαβουλὼν καὶ Νεφθαλείμ as modifying Matthew’s entire sentence, such that Jesus’ leaving Nazareth and taking up residence in Capernaum all took place within the boundaries of Zebulun (Nazareth) and Naphtali (Capernaum).[36] However, as even Nolland, a proponent of this interpretation, admitted, this approach is difficult to reconcile with Matthew’s syntax.[37] Thus the effort to save Matthew’s geographical accuracy comes at the expense of the author of Matthew’s ability to write Greek.

Another approach might be to suppose that the author of Matthew’s placement of Zebulun’s territory on the lakeshore reflects a first-century understanding of the tribal allotments. Like the author of Matthew, Josephus claimed that Zebulun’s territory extended to the Sea of Galilee:

Ζαβουλωνῖται δὲ τὴν μέχρι Γενησαρίδος καθήκουσαν δὲ περὶ Κάρμηλον καὶ θάλασσαν ἔλαχον

They of Zabulon obtained the land which reaches to the (lake of) Genesar and descends well-nigh to Carmel and the sea. (Ant. 5:84; Loeb)[38]

Similarly, a rabbinic tradition may imply that Zebulun’s territory reached the lakeshore:

[זבולן לחוף ימים ישכן] ד″א זבולן לחוף ימים מה ראה יעקב שבירך זבולן ואחר כך יששכר, והלא יששכר גדול ממנו ויששכר היה ראוי לברך תחילה, אלא צפה וראה בית המקדש שעתיד ליחרב, ועתיד סנהדרי שתעקר משבטו שליהודה ולהיקבע בחלקו שלזבולון, שכתחילה גלתה לה סנהדרי וישבה לה ביבנה, ומיבנה לאושה, ומאושה לשפרעם, ומשפרעם לבית שערים, ומבית שערים לציפורי, וציפורי היה בחלקו שלזבולן, ואחרכך גלתה לטיבריה

Another interpretation: Zebulun will dwell by the shore of the seas [Gen. 49:13]. Why did Jacob see fit to bless Zebulun and only afterward Issachar? Was not Issachar older than he and therefore worthy to be blessed first? Rather, Jacob had a vision and saw that the Temple would be destroyed and the Sanhedrin would be uprooted from the tribe of Judah and relocated to the tribe of Zebulun. For at first the Sanhedrin was exiled to Yavneh [in Judah—DNB and JNT], and from Yavneh to Usha, and from Usha to Shepharam, and from Shepharam to Bet Shearim, and from Bet Shearim to Tzippori. And Tzippori was in Zebulun’s portion. And after that it was exiled to Tiberias. (Gen. Rab. 97:13 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 3:1220-1221])

At first glance this rabbinic tradition seems only to support the interpretation of Matt. 4:13 that places Nazareth in the territory of Zebulun, since Tzippori (Sepphoris) is only about three and a quarter miles from Nazareth.[39] But while this tradition singles out Sepphoris as belonging to Zebulun, it may be that all of the Galilean seats of the Sanhedrin—Usha, Shepharam, Bet Shearim, Tzippori and Tiberias—were understood to be within Zebulun’s territory, since the rabbinic tradition mentions only two tribes (Judah and Zebulun) in which the Sanhedrin was located. In any case, the tradition cannot have understood Usha, Shepharam or Bet Shearim to have been located in Issachar’s territory, since this would undermine the explanation for why Zebulun was blessed first despite Issachar’s seniority. Moreover, the reference to Zebulun’s connection to the sea only makes sense if Tiberias was located in Zebulun’s territory, for all the other Galilean seats of the Sanhedrin were landlocked. Thus, like Josephus, this rabbinic tradition likely extends Zebulun’s territory to the Sea of Galilee.

“The Wanderings of the Sanhedrin after 70 C.E.,” a map from Understanding the Jewish World from Roman to Byzantine times: Mishnah, Talmud, the Sages: An Introductory Atlas by Shmuel Safrai and Michael Avi-Yonah (Jerusalem: Carta, 2015), 11.It is possible, therefore, that the author of Matthew knew of contemporary traditions that extended Zebulun’s borders to the lake, or he may have reached this conclusion based on his own reading of Gen. 49:13,[40] which places Zebulun’s dwelling at the παράλιος (paralios, “seacoast”), which is roughly synonymous with παραθαλάσσιος (parathalassios, “by the sea”). But even if the author of Matthew did believe that Zebulun’s territory extended to the lake, his placement of Capernaum within the borders of two tribes, Zebulun and Naphtali, shows that he was not concerned about geographical precision[41] but about forcing Isa. 8:23 into a prediction of Jesus’ movements so that the stirring words of Isa. 9:1 (“the people dwelling in darkness have seen a great light,” etc.) could be applied to Jesus’ ministry.[42] It is unlikely that “the land of Zebulun” or “the land of Naphtali” had any more definite meaning for the author of Matthew than the other locations he pulled from the Isaiah passage (“way of the sea,” “beyond the Jordan,” “Galilee of the Gentiles”). These toponyms evoked for the author of Matthew the region(s) in which Jesus had performed miracles and proclaimed his message. For the author of Matthew that evocation was sufficient to justify his claim that Jesus’ residence in Capernaum fulfilled Isaiah’s prophecy.

L4-7 ἵνα πληρωθῇ τὸ ῥηθὲν διὰ Ἠσαΐου τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος (Matt. 4:14). In Matt. 4:14 we encounter the uniquely Matthean fulfillment formula ἵνα/ὅπως πληρωθῇ τὸ ῥηθὲν διά + personal name + τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος, also found in Matt. 8:17 and Matt. 12:17 (cf. Matt. 2:23; 13:35). This is only one variation of several stereotyped formulae, such as ἵνα πληρωθῇ τὸ ῥηθὲν (ὑπὸ κυρίου) διὰ τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος (Matt. 1:22; 2:15; 21:4) and τότε ἐπληρώθη τὸ ῥηθὲν διά + personal name + τοῦ προφήτου λέγοντος (Matt. 2:17; 27:9), that distinguish Matthew’s Gospel from the other Synoptic Gospels.[43] These fulfillment formulae and the quotations they introduce are clearly the author of Matthew’s redactional contribution to the synoptic tradition.

L8-17 (Matt. 4:15-16). Some scholars have maintained that Matthew’s quotation of Isa. 8:23-9:1 is independent of LXX,[44] some going so far as to claim that it represents a fresh—and in places more accurate—translation of the Hebrew text of Isaiah.[45] But while the quotation in Matt. 4:15-16 does indeed deviate from LXX, it is clearly derived from it.[46] Three features of Matthew’s quotation are best explained as due to Matthew’s dependence on LXX:

- The unusual spelling of Naphtali as Νεφθαλίμ (Nefthalim) agrees with the LXX translation of Isa. 8:23 (see below, Comment to L8-9).

- The incorrect rendering of גְּלִיל הַגּוֹיִם (gelil hagōyim, “region of the Gentiles”) as Γαλιλαία τῶν ἐθνῶν (Galilaia tōn ethnōn, “Galilee of the Gentiles”) agrees with LXX (see below, Comment to L12).

- The surprising rendering of בְּאֶרֶץ צַלְמָוֶת (be’eretz tzalmāvet, “in the land of the shadow of death”) as ἐν χώρᾳ καὶ σκιᾷ θανάτου (en chōra kai skia thanatou, “in the country and in the shadow of death”) agrees with LXX (see below, Comment to L16).

Since these three translations are not the most natural renderings of the Hebrew text and are not likely to have been formulated independently, the most probable and credible explanation for these agreements between Matthew’s quotation and LXX is Matthew’s direct dependence on LXX.

In LXX the Isaiah passage reads as follows:

τοῦτο πρῶτον ποίει, ταχὺ ποίει, χώρα Ζαβουλων, ἡ γῆ Νεφθαλιμ ὁδὸν θαλάσσης καὶ οἱ λοιποὶ οἱ τὴν παραλίαν κατοικοῦντες καὶ πέραν τοῦ Ιορδάνου, Γαλιλαία τῶν ἐθνῶν, τὰ μέρη τῆς Ιουδαίας ὁ λαὸς ὁ πορευόμενος ἐν σκότει, ἴδετε φῶς μέγα· οἱ κατοικοῦντες ἐν χώρᾳ καὶ σκιᾷ θανάτου, φῶς λάμψει ἐφ̓ ὑμᾶς

Do this first, do it soon, O country of Zebulun, the land of Naphtali, the way of the sea, and the rest of those dwelling on the seashore, and across the Jordan, Galilee of the Gentiles, the parts of Judea! O people walking in darkness, view a great light! And those dwelling in the country and in the shadow of death, a light will shine on you. (Isa. 8:23-9:1)

The most important differences between Matthew’s quotation and LXX are the omission of τοῦτο πρῶτον ποίει, ταχὺ ποίει (“do this first, do it soon”), οἱ λοιποὶ οἱ τὴν παραλίαν κατοικοῦντες (“the rest of those dwelling on the seashore”) and τὰ μέρη τῆς Ιουδαίας (“the parts of Judea”). The first and third of these omissions can be explained by the fact that they do not serve the author of Matthew’s redactional purpose. The author of Matthew did not wish to issue a summons but to present a predictive prophecy, so he dropped the opening imperative. Similarly, since the author of Matthew desired to present a prophecy of Jesus’ Galilean ministry, he dropped the reference to Judea.[47] His reason for dropping the reference to those dwelling on the seashore is less obvious. It may be that the author of Matthew felt that “the way of the sea” was sufficient to evoke the Sea of Galilee setting of Jesus’ ministry, or it may be that he wished to avoid the verb κατοικεῖν (katoikein, “to dwell”), which he changed to καθῆσθαι (kathēsthai, “to sit,” “to dwell”) elsewhere in this passage (see below, Comment to L15).

The author of Matthew also made a number of smaller adaptations to LXX. Many of these changes can also be explained in light of the author of Matthew’s redactional interests. For instance, in place of “region of Zebulun, the land of Naphtali” in L8-9 the author of Matthew wrote “land of Zebulun and land of Naphtali,” thereby fusing the two distinct geographical units into a single entity, which agrees with the author of Matthew’s localizing of Capernaum “in the borders of Zebulun and Naphtali” (Matt. 4:13 [L3]). The change from “walking in darkness” to “sitting in darkness” in L13 may be due to the author of Matthew’s preference for the static image of people “sitting” to the dynamic image of people “walking” because the static image better conveys a sense of anticipation and longing for deliverance, whereas the dynamic image suggests that the people walking about in the darkness are getting along with their lives. Having adopted the image of “sitting” in L13, the author of Matthew changed LXX’s οἱ κατοικοῦντες ἐν χώρᾳ (“the ones dwelling in the country”) to τοῖς καθημένοις ἐν χώρᾳ (“to the ones sitting in the country”; L15-16) for the sake of consistency. Also for consistency’s sake, the author of Matthew changed LXX’s imperative “View a great light!” to “they saw a great light,” which like his omission of LXX’s imperatives “Do this first! Do it soon!” allowed him to transform Isaiah’s exhortation into a predictive prophecy. Finally, the change from “a light will shine on you” to “a light has dawned on them” in L17 may be intended to allude to similar prophecies such as τότε ἀνατελεῖ ἐν τῷ σκότει τὸ φῶς σου (“then your light will dawn in the darkness”; Isa. 58:10)[48] or καὶ ἀνατελεῖ ὑμῖν τοῖς φοβουμένοις τὸ ὄνομά μου ἥλιος δικαιοσύνης (“and the sun of righteousness will dawn for you who fear my name”; Mal. 3:20 [Eng.: Mal. 4:2]),[49] or even ἀνατελεῖ ἄστρον ἐξ Ιακωβ (“a star will arise out of Jacob”; Num. 24:17).[50]

A few of the author of Matthew’s adaptations do bring the quotation in Matt. 4:15-16 closer to the Hebrew text of Isaiah than LXX’s translation. Thus 1) Matthew’s γῆ Ζαβουλὼν καὶ γῆ Νεφθαλίμ (“land of Zebulun and land of Naphtali”) in L8-9 is closer to אַרְצָה זְבֻלוּן וְאַרְצָה נַפְתָּלִי (“toward the land of Zebulun and toward the land of Naphtali”) than χώρα Ζαβουλων, ἡ γῆ Νεφθαλιμ (“country of Zebulun, the land of Naphtali”);[51] 2) in L11 Matthew omits the conjunction καί (kai, “and”) that precedes πέραν τοῦ Ιορδάνου (“beyond the Jordan”), which is like עֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן (“beyond the Jordan”) in the Hebrew text;[52] 3) Matthew’s verb εἶδεν (eiden, “it saw”) in L14 is closer to the רָאוּ (rā’ū, “they saw”) of MT than LXX’s imperative ἴδετε (“See [plur.]!”);[53] 4) Matthew’s verb καθῆσθαι (kathēsthai, “to sit”) in L15 is closer to the verb in the Hebrew text (יָשַׁב [“to sit,” “to dwell”]) than LXX’s κατοικεῖν (“to dwell,” “to reside”);[54] and 5) Matthew’s third-person plural pronoun αὐτοῖς (“to them”) in L17 is closer to the third-person plural suffix attached to the preposition עַל (‘al, “upon”) at the end of Isa. 9:1 (עֲלֵיהֶם [“upon them”]) than LXX’s second-person plural pronoun ὑμᾶς (hūmas, “you”).[55] However, since these changes can be explained on the basis of the author of Matthew’s redactional interests, the similarities to the Hebrew text are probably coincidental. This conclusion is supported by the fact that other Matthean adaptations of the LXX text further distance his quotation from the Hebrew original,[56] a strong indication that the author of Matthew was not attempting to bring the LXX quotation in line with the Hebrew text.[57] Thus 1) Matthew’s ὁ λαὸς ὁ καθήμενος (“the people sitting”) in L13 is further from the Hebrew text (הָעָם הַהֹלְכִים [“the people walking”]) than LXX’s ὁ λαὸς ὁ πορευόμενος (“the people walking”); 2) Matthew’s word order in L14 (φῶς εἶδεν μέγα [“a light | it saw | big”]) is further from the Hebrew text (רָאוּ אוֹר גָּדוֹל [“they saw | a light | big”]) than LXX’s ἴδετε φῶς μέγα (“see! | a light | big”);[58] 3) Matthew’s verb ἀνατέλλειν (anatellein, “to dawn,” “to rise”) in L17 is further from the Hebrew text (נָגַהּ [nāgah, “shine”]) than is LXX’s λάμπειν (lampein, “to shine”);[59] and 4) the dative case of Matthew’s third-person plural pronoun (αὐτοῖς [avtois, “to them”]) in L17 is further from the preposition in the Hebrew text (עַל [‘al, “upon”]) than is LXX’s preposition ἐφ̓ (ef, “upon”).[60]

L8-9 γῆ Ζαβουλὼν καὶ γῆ Νεφθαλείμ (Matt. 4:15). In L8 the author of Matthew used the Septuagintal form of the name “Zebulun.” His choice is significant because there were other options available. For example, he could have written γῆ Ζαβουλωνῖτις (gē Zaboulōnitis, “Zebulunite land”; cf. Jos., Ant. 7:58) or Ζαβουλωνῖται (Zaboulōnitai, “Zebulunites [land]”; Ant. 5:84). Matthew’s agreement with the LXX form of the name points to LXX dependence.

LXX dependence is even clearer in L9, where the author of Matthew adopted LXX’s spelling of Naphtali as Νεφθαλίμ (Nefthalim). This spelling only occurs 9xx in LXX,[61] compared to over forty instances of the spelling Νεφθαλι (Nefthali),[62] which is closer to the Hebrew form נַפְתָּלִי (naftāli). The fact that both Matthew and LXX use the rare spelling Νεφθαλίμ in their versions of Isa. 8:23 can be no coincidence.[63] The author of Matthew relied on LXX for his Isaiah quotation.

L10 ὁδὸν θαλάσσης (Matt. 4:15). The author of Matthew’s phrase ὁδὸν θαλάσσης (hodon thalassēs, “way of [the] sea”) agrees with LXX,[64] which is significant because there were other options for rendering דֶּרֶךְ הַיָּם (derech hayām, “way of the sea”) of which an independent translator of the Hebrew text might have availed himself. In Ezek. 41:12 the LXX translators rendered דֶּרֶךְ הַיָּם as πρὸς θάλασσαν (pros thalassan, “by the sea”), a translation that would have been more to the author of Matthew’s purpose. The phrase דֶּרֶךְ הַיָּם might also have been rendered ὁδὸν τῆς θαλάσσης (hodon tēs thalassēs, “way of the sea”), which, by including the definite article, is a more exact translation. The conformity of Matthew’s quotation to LXX points to the author of Matthew’s reliance on this translation.

L11 πέραν τοῦ Ἰορδάνου (Matt. 4:15). Matthew’s phrase πέραν τοῦ Ἰορδάνου (peran tou Iordanou, “beyond the Jordan”) agrees with LXX,[65] despite other options being available. In Josh. 7:7, for instance, the LXX translators rendered עֵבֶר הַיַּרְדֵּן (‘ēver hayardēn, “beyond the Jordan”) as παρὰ τὸν Ιορδάνην (para ton Iordanēn, “by the Jordan”), which might seem to be more congenial to the author of Matthew’s purpose. Other options might have been ὑπὲρ τὸν Ιορδάνην (hūper ton Iordanēn, “beyond the Jordan”; cf. Jos., J.W. 2:43; 4:450; 6:201; Ant. 5:93), τὸν περαῖον τοῦ Ἰορδάνου (ton peraion tou Iordanou, “the country opposite the Jordan”; cf. Jos., Ant. 5:74), τὴν πέραν τοῦ Ἰορδάνου χώραν (tēn peran tou Iordanou chōran, “the country beyond the Jordan”; cf. Jos., Ant. 8:37), or even just τὰ πέραν τοῦ Ἰορδάνου (ta peran tou Iordanou, “the parts beyond the Jordan”; cf. Jos., Ant. 7:198; 13:14). In view of the numerous options available to the author of Matthew, the conformity of Matthew’s quotation to LXX’s wording is telling.

Nevertheless, the author of Matthew did slightly deviate from LXX by omitting the καί (kai, “and”) before πέραν τοῦ Ἰορδάνου. This omission resembles the lack of a connecting vav in the Hebrew text.[66] Nevertheless, the author of Matthew may have had reasons of his own, unrelated to the Hebrew text of Isa. 8:23, for omitting LXX’s καί. Scholars have noted that “beyond the Jordan” does not really suit Matthew’s purpose of describing Jesus’ move from Nazareth to Capernaum,[67] unless, that is, the author of Matthew wrote from an eastern perspective. If the author of Matthew and the community for whom he wrote were located in Syria, as many scholars suppose, then the author of Matthew and his readers might have understood “beyond the Jordan” as qualifying “land of Zebulun and land of Naphtali,” since from their geographical point of view these areas were beyond the Jordan to the west.[68] However, in order for “beyond the Jordan” to qualify “land of Zebulun and land of Naphtali,” LXX’s καί had to be omitted. Alternatively, the author of Matthew’s desire to make Zebulun and Naphtali into a single entity might have led him to join these two items with καί and to omit the rest of LXX’s conjunctions in Isa. 8:23. This explanation rests on the supposition that the author of Matthew had as imprecise an understanding of what was meant by “Galilee of the Gentiles” as he did of “land of Zebulun and land of Naphtali,” such that he believed that the Galilee encompassed land on both sides of the River Jordan.[69] In either case, the omission of LXX’s καί can be explained by the author of Matthew’s redactional interests.

L12 Γαλειλαία τῶν ἐθνῶν (Matt. 4:15). Like LXX, Matthew’s quotation of Isa. 8:23 refers to Γαλιλαία τῶν ἐθνῶν (Galilaia tōn ethnōn, “Galilee of the Gentiles”).[70] The LXX translators had misunderstood the prophet’s informal designation גְּלִיל הַגּוֹיִם (gelil hagōyim, “district of the foreigners”) as a proper name, and the author of Matthew clearly shared their misconception.[71] While it is conceivable that the LXX translators and the author of Matthew independently arrived at this misunderstanding of Isaiah’s words, the numerous points of agreement between Matthew’s quotation and LXX make Matthean dependence on LXX the simpler and more obvious explanation.

L13 ὁ λαὸς ὁ καθήμενος ἐν σκότει (Matt. 4:16 [best reading]). The words ὁ λαός (ho laos, “the people”) and ἐν σκότει (en skotei, “in darkness”) are identical to the LXX translation.[72] These agreements of Matthew’s quotation with LXX must be emphasized because neither translation is inevitable. An independent translator could have rendered Isaiah’s הָעָם (hā‘ām, “the people”) as τὸ γένος (to genos, “the race”; cf. Gen. 26:10) or τὸ ἔθνος (to ethnos, “the people group”). Likewise, an independent translator could have rendered Isaiah’s בַּחֹשֶׁךְ (baḥoshech, “in the darkness”) as ἐν τῷ σκότει (en tō skotei, “in the darkness”; cf. Josh. 2:5; Isa. 49:9; 58:10) or εἰς τὸ σκότος (eis to skotos, “in the darkness”; cf. Isa. 47:5) or ἐν τῷ γνόφῳ (en tō gnofō, “in the darkness”; cf. Job 17:13). The agreement of Matthew’s quotation with LXX in these respects points to Matthew’s Septuagintal dependence.

Where Matthew’s quotation disagrees with LXX in L13, it sharply diverges from the Hebrew text. Whereas the LXX translators rendered הַהֹלְכִים (haholchim, “the ones walking”) as ὁ πορευόμενος (ho porevomenos, “the one walking”), Matthew’s quotation has ὁ καθήμενος (ho kathēmenos, “the one sitting”).[73] As we stated above in Comment to L8-17, it seems likely that the author of Matthew changed LXX’s wording because he preferred the static image of the people sitting and waiting passively for deliverance to the dynamic image of people actively walking about in the darkness, as though they had begun to cope on their own. It also appears that the author of Matthew had a redactional preference for the verb καθῆσθαι (kathēsthai, “to sit”), since this verb appears several times in Matthew, either in unique passages or without agreement from the synoptic parallels.[74] That the author of Matthew’s adaptation of LXX’s translation of Isa. 9:1 takes the quotation further away from the Hebrew text in such a conspicuous manner while at the same time serving his redactional interest argues against the view that the Isaiah quotation in Matt. 4:15-16 represents a direct translation of the Hebrew text independent of LXX.

L14 φῶς εἶδεν μέγα (Matt. 4:16). Matthew’s noun φῶς (fōs, “light”) and his adjective μέγας (megas, “big”) are identical to those in LXX, but other options would have been available to an independent translator. Instead of φῶς, an independent translator might have rendered אוֹר (’ōr, “light”) as φωτισμός (fōtismos, “light”; cf. Ps. 26[27]:1; 43[44]:4; 77[78]:14; 138[139]:11; Job 3:9) or φέγγος (fengos, “light”; cf. Job 22:28; 41:10).[75] And instead of μέγας, an independent translator might have chosen a less literal option such as ἱκανός (hikanos, “sufficient,” “large”; cf. Acts 22:6) or λαμπρός (lampros, “bright”).

The mood and person of the verb “to see” are different in Matthew and LXX. Whereas Matthew’s verb is indicative and in the third-person singular, the LXX verb is imperative and in the second-person plural. While these differences might be explained as independent renderings of an unpointed ראו in Isa. 9:1,[76] we must not ignore that the author of Matthew is presenting a prophecy he believes was fulfilled not by his readers but by the people of Galilee who witnessed Jesus’ teaching and healing. Therefore, a descriptive prophecy in the third person suited the author of Matthew better than a second-person exhortation. So it is unlikely that the deviation of Matthew’s quotation from LXX reflects anything other than the author of Matthew’s redactional concerns.

L15 καὶ τοῖς καθημένοις (Matt. 4:16). Here, Matthew’s quotation differs significantly from LXX. Whereas LXX has the nominative case and a participial form of κατοικεῖν (katoikein, “to dwell,” “to reside”), Matthew’s quotation uses the dative case and a participial form of καθῆσθαι (kathēsthai, “to sit”). It is true that καθῆσθαι is a more literal equivalent of יָשַׁב (yāshav, “sit,” “dwell”), the verb that occurs in the Hebrew text of Isa. 9:1, than κατοικεῖν,[77] but there are two reasons unrelated to the Hebrew text of Isaiah that might explain why the author of Matthew preferred “sit” to “reside.” First, as we noted above in Comment to L13, the author of Matthew probably preferred vocabulary that evoked passive yearning for deliverance, whereas “reside” might sound as if the people in death’s shadow were doing their best to make themselves comfortable by making homes for themselves. The other reason is that the author of Matthew had already used the verb κατοικεῖν to describe Jesus’ making a home for himself in Capernaum. Since the author of Matthew did not want to include Jesus among those upon whom the light dawned—for the author of Matthew, Jesus was the dawning light—he opted for a different verb.[78] Thus it is not necessary to suppose that the author of Matthew worked from or even knew the Hebrew text of Isaiah to explain how Matthew’s quotation arrived at a more literal equivalent of יָשַׁב than LXX.

L16 ἐν χώρᾳ καὶ σκιᾷ θανάτου (Matt. 4:16). The wording of Matthew’s quotation in L16 conforms exactly with LXX and clearly points to the author of Matthew’s dependence on this translation.[79] The conjunction καί (“and”) has no equivalent in the Hebrew text of Isa. 9:1, and other options such as ἐν (τῇ) γῇ σκιᾶς θανάτου (en [tē] gē skias thanatou, “in the land of the shadow of death”) and ἐπὶ (τῆς) γῆς σκιᾶς θανάτου (epi [tēs] gēs skias thanatou, “on the land of the shadow of death”) would have been available to an independent translator.

L17 φῶς ἀνέτειλεν αὐτοῖς (Matt. 4:16). The wording of Matthew’s quotation in L17 is unlike LXX and the Hebrew text of Isa. 9:1.[80] As we stated above in Comment to L8-17, by changing LXX’s wording the author of Matthew may have intended to allude to some other messianic prophecy such as Balaam’s prophecy of a star coming from Jacob (Num. 24:17), a prophecy that evidently influenced the author of Matthew’s telling of the story of the Magi, or Malachi’s reference to the sun of righteousness arising with healing in its wings (Mal. 3:20), which would not be unlikely since elsewhere in his Gospel the author of Matthew interpreted Malachi’s prophecies messianically (Matt. 11:10). In any case, Matthew’s wording in L17 does not reflect a translation of the Hebrew text of Isa. 9:1 independent of LXX.

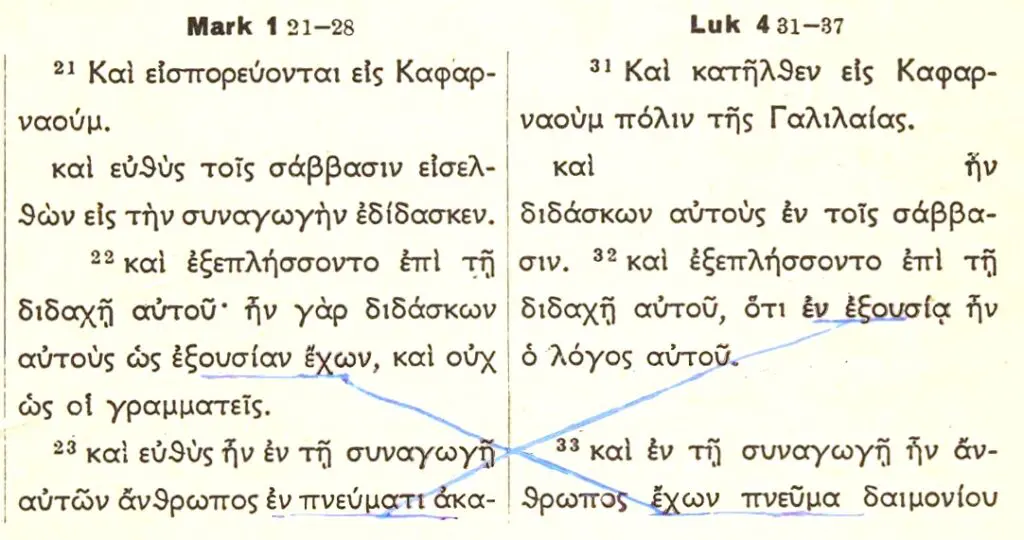

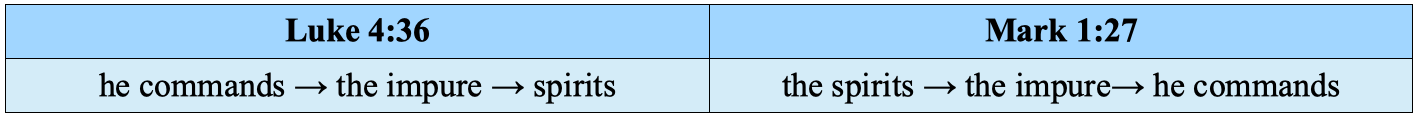

L18-21 In L18-21 we encounter a curious inverse relationship between the wording of the Lukan and Markan versions of Teaching in Kefar Nahum. Luke begins with Jesus’ teaching (L20), moves on to the audience (L20), and concludes with the Sabbath (L21). Mark begins with the Sabbath (L18), moves on to the audience (L19), and ends with Jesus’ teaching (L20).

The inverse relationship is obscured somewhat by the fact that in Mark’s version the reference to Jesus’ audience is oblique, being inferred from Jesus’ entry into the synagogue (L19), whereas Luke’s reference to Jesus’ audience in L20 is explicit (“them”), even if it is non-specific.

Inversion of Luke’s word order was one of the author of Mark’s redactional techniques.[81]

L18 καὶ εὐθέως τοῖς σάββασιν (Mark 1:21). Although in L18 the text of Codex Vaticanus reads εὐθέως (evtheōs, “immediately”), critical texts indicate that εὐθύς (evthūs, “immediately”) was the original reading. In Mark’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum εὐθύς occurs three times (L18, L35, L73), each at a change of scene. The first instance of εὐθύς marks the beginning of the teaching scene in the synagogue, the second instance of εὐθύς marks the exorcism scene in the synagogue, and the third instance of εὐθύς marks the closing scene in which Jesus’ fame spreads far and wide. Since the repeated use of εὐθύς is characteristic of Markan redaction,[82] we agree with those scholars who regard its presence in L18 as a Markan addition to the original story.[83]

Mark’s use of a plural form of σάββατον (sabbaton, “Sabbath”) to refer to one particular Sabbath is not ungrammatical,[84] but neither is it necessary. The author of Mark could just as easily have written τῷ σαββάτῳ (tō sabbatō, “on the Sabbath”) and no one would have skipped a beat. On the other hand, in Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum the plural form of σάββατον does serve a necessary function, since Luke’s version describes Jesus’ habit of teaching regularly on the Sabbath.[85] From the perspective of Lindsey’s hypothesis of Markan dependence on Luke, Mark’s use of τοῖς σάββασιν (tois sabbasin, “in the Sabbaths”) appears to be a verbal relic, a linguistic feature carried over from an earlier source that no longer has a vital function in its present context.

Having picked up the plural form of σάββατον from Luke in Teaching in Kefar Nahum, the author of Mark went on to use it in Lord of Shabbat (Mark 2:23) and Man’s Withered Hand (Mark 3:2, 4), where Luke’s version has singular forms of σάββατον (Luke 6:1, 7, 9).[86] Apart from its being relatively infrequent, Mark’s use of σάββατον in the plural with a singular sense fits the profile of a Markan stereotype.

L19 εἰσελθὼν εἰς τὴν συναγωγὴν (Mark 1:21). The author of Mark is careful to make Jesus enter Capernaum’s synagogue at the beginning of the pericope, thereby creating greater unity between Parts One and Two of Teaching in Kefar Nahum than in the version in Luke. Luke’s version of the pericope does not specify a location for Jesus’ habitual Sabbath day lessons,[87] and it may be that Jesus, like many rabbinic sages, taught the people out of doors in an open-air venue such as an orchard, vineyard or hillside.[88] The Sabbath was an ideal time for an itinerant sage to teach audiences larger than the closed group of his full-time disciples. On the Sabbath, farmers, day laborers, servants and other workers were released from their daily routines and had leisure to attend a sage’s public lessons. The reputation Jesus gained from these informal lessons may explain how Jesus came to be invited to formally address the members of the Capernaum synagogue. Compared to the Lukan version of the story, Mark’s version elevates Jesus’ status by having Jesus “immediately” enter the synagogue and begin teaching, whereas in Luke’s version Jesus’ invitation to teach in the synagogue had to be earned. It is hard to believe that the author of Luke would have demoted Jesus and presented a less unified version of the story by omitting the reference to the synagogue at the opening of the pericope had it occurred in his source. On the other hand, the author of Mark’s addition of the synagogue to the version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum he read in Luke makes perfect sense. We therefore regard Mark’s reference in L19 to Capernaum’s synagogue as redactional.

L20 ἦν διδάσκων αὐτοὺς (GR). Hebrew does not have an exact equivalent to the imperfect tense, which Mark employs in L20 (ἐδίδασκεν [edidasken, “he was teaching”]). To describe habitual action Mishnaic Hebrew used הָיָה + participle, which is equivalent to Luke’s ἦν + participle (ἦν διδάσκων [ēn didaskōn, “he was teaching”]) in L20. Luke’s Hebraic Greek might be due to his use of a source translated from Hebrew. For that reason we have accepted Luke’s wording in L20 for GR.

וְהָיָה מְלַמֵּד אֹתָם (HR). On reconstructing διδάσκειν (didaskein, “to teach”) with לִמֵּד (limēd, “teach”), see Lord’s Prayer, Comment to L5. Neither the Lukan nor the Markan versions of Teaching in Kefar Nahum indicate the content of Jesus’ teaching. In terms of content, the author of Matthew was probably on the right track when he made the Sermon on the Mount the replacement for Teaching in Kefar Nahum. Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount contains two epitomes of Jesus’ message: the Beatitudes and the Lord’s Prayer. Both the Beatitudes and the Lord’s Prayer describe the Kingdom of Heaven not merely as a concept but as a way of life to be pursued. Since the Kingdom of Heaven was the focus of so much of Jesus’ teaching, the odds that Jesus’ teaching in Capernaum concerned this subject are good.

L21 ἐν τοῖς σάββασιν (Luke 4:31). Since Luke’s sentence describes Jesus’ habitual practice of teaching on the Sabbath, we think it is best to interpret the plural form of σάββατον (sabbaton, “Sabbath”) in L21 literally: Jesus taught on several consecutive Sabbaths.[89]

בַּשַּׁבָּתוֹת (HR). In LXX most instances of σάββατον occur as the translation of שַׁבָּת.[90] Likewise, the LXX translators rendered most instances of שַׁבָּת as σάββατον.[91] In any case, there can hardly be any more suitable option for HR than שַׁבָּת, since the noun σάββατον is a Hellenized form of the Hebrew term שַׁבָּת.[92]

L22-25 καὶ ἐγένετο ὅτε ἐτέλεσεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς τοὺς λόγους τούτους (Matt. 7:28). Matthew’s wording in L22-25 is Hebraic and contains two apparent agreements with Luke against Mark, namely ἐγένετο (egeneto, “it was”) in L22 (≈ Luke, L58) and the noun λόγος (logos, “word”) in L25 (≈ Luke, L31). Nevertheless, these minor agreements are distant and, probing deeper, we discover that the source for Matthew’s wording in L22-25 is not Anth.’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum but Anth.’s version of Sermon’s End (cf. Luke 7:1).[93] What the author of Matthew has done in Matt. 7:28-29 is to combine Anth.’s version of Sermon’s End (Matt. 7:28a) with Mark’s version of the congregation’s reaction to Jesus in Teaching in Kefar Nahum (Matt. 7:28b-29).[94] This explains why Matthew’s wording in Matt. 7:28a is so Hebraic (the author of Matthew followed a Hebraic-Greek source [Anth.]) and reveals that the apparent minor agreements with Luke in L22 (≈ L58) and L25 (≈ L31) are in fact mere coincidences. Thus Matthew’s wording in L22-25 cannot help us with the reconstruction of Teaching in Kefar Nahum, but it is vital for reconstructing Anth.’s conclusion to Jesus’ most famous sermon.

L22-34 (Mark 1:22 ∥ Luke 4:32). The verse that makes Teaching in Kefar Nahum a two-part pericope is Luke 4:32 (∥ Mark 1:22). Without this verse Teaching in Kefar Nahum would form a single cohesive narrative.[95] It is also clear that the people’s reaction to Jesus’ teaching in Luke 4:32 (∥ Mark 1:22) parallels the people’s reaction to Jesus’ exorcism in Luke 4:36 (∥ Mark 1:27). These observations have led some scholars to suppose that the people’s reaction to Jesus’ teaching in L22-34 is an interpolation modeled on the people’s response to the exorcism in L58-70.[96] We agree with this conclusion, but the question remains: Who made the interpolation? Was it the author of Mark, who was then followed by the author of Luke? Or was it the author of Luke, who was followed by the author of Mark? Whereas most scholars today would presume the former, we believe the latter option offers a more adequate explanation for why and how the interpolation was made.

Flusser argued that Luke 4:32 was composed on the basis of a faulty understanding of Luke 4:36.[97] According to Luke 4:36, the congregants were astounded at the exorcism Jesus performed and wondered aloud, τίς ὁ λόγος οὗτος (tis ho logos houtos, “What is this logos?”). This question was intended to be understood as asking, “What is this thing?” but the redactor who penned Luke 4:32 (mis)understood τίς ὁ λόγος οὗτος as asking, “What is this word?” Evidently the redactor supposed Jesus had uttered a mysterious word of power that defeated the demon.[98] In any case, this misunderstanding was possible because the more usual meaning of λόγος (logos) is “word.” The redactor did not realize that the noun λόγος in the people’s question τίς ὁ λόγος οὗτος (“What is this logos?”) was a translation of the Hebrew noun דָּבָר (dāvār, “word,” “thing”), which in context would have naturally been understood as “What is this happening?” or “What’s going on here?”[99] But in Greek translation the noun λόγος in the people’s question is conspicuous (cf. Mark’s [para]phrasing of the question as τί ἐστιν τοῦτο [ti estin touto, “What is this?”]), and it was precisely because λόγος stands out that the redactor attributed to it a significance the translator did not intend. Believing that the people had reacted to Jesus’ word of command, whose authority the demons respected, the redactor composed a response to Jesus’ teaching in which the people react to the authority of Jesus’ word.

Flusser’s explanation works with regard to Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum, but does not apply to Mark’s version. Mark’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum does not contain the word λόγος. Neither can Mark 1:22 be construed as a misunderstanding of Mark 1:27. On the contrary, the people’s reaction to the exorcism in Mark 1:27 presupposes the notion that Jesus’ teaching was authoritative, which is first expressed in Mark 1:22. According to Mark 1:27, people respond by saying, “Not only does Jesus teach a new authoritative doctrine, he also commands demons and they listen to him.” In both Mark 1:22 and Mark 1:27 Jesus’ authority is manifested in his teaching; not so in Luke 4:36, where Jesus’ authority is (exclusively) manifested in his ability to issue demons orders. Mark 1:27 harks back to Mark 1:22, tying Parts One and Two of the pericope together, but Luke 4:36 does not require Luke 4:32 to make sense.

The fact that the people’s questions in Mark 1:22 and Mark 1:27 are interconnected, whereas the people’s question in Luke 4:36 is independent of the question in Luke 4:32, is significant. It either suggests that the author of Mark took steps to integrate the two parts of the narrative he found in Luke or that the author of Luke took steps to disentangle the two parts of the narrative he found in Mark. We find the former explanation to be more plausible. The likelihood that Luke 4:32 shows that the original meaning of the people’s question in Luke 4:36 was lost in translation is also significant. It suggests that the wording of the people’s question in Luke 4:36 is more primitive than the parallel wording in Mark 1:27.

In Flusser’s view, the redactor who penned Luke 4:32 was pre-Lukan, and the reason he penned the people’s reaction to Jesus’ teaching was that Jesus’ appearance in Capernaum’s synagogue was the first occasion on which Jesus was reported to have taught in public in the pre-Lukan Gospel.[100] As this was the first account of Jesus’ teaching, the pre-Lukan editor was not content merely to mention this momentous occasion in passing. He therefore composed Luke 4:32 on the model of Luke 4:36 in order to give greater prominence to Jesus’ teaching while retaining the style of his source. The reason Flusser believed that the redactor who penned Luke 4:32 was pre-Lukan is that in Luke’s Gospel Teaching in Kefar Nahum does not describe the first occasion on which Jesus taught publicly. In Luke, Jesus’ first public address is delivered in Nazareth (Luke 4:14-30). Flusser assumed that the author of Luke was responsible for the position of Nazarene Synagogue, having inserted it between Return to the Galil (Luke 4:14-15) and Teaching in Kefar Nahum (Luke 4:31-37). But as we have discussed in the Story Placement section above, there is strong evidence (two points of Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark) to suggest that the author of Luke did not insert Nazarene Synagogue between Return to the Galil and Teaching in Kefar Nahum, but that the Return to the Galil→Nazarene Synagogue→Teaching in Kefar Nahum sequence was already present in his source. We also discussed that, despite retaining this sequence, the author of Luke was eager to prevent his readers from forming the impression that Jesus’ teaching generally received a negative response from his audience (as happened in Nazareth). The author of Luke therefore added a reference to the people’s receptivity to Jesus’ teaching in Return to the Galil to counterbalance the unreceptiveness Jesus’ message encountered in Nazareth.[101] We believe the same motivation accounts for the insertion of Luke 4:32 into Teaching in Kefar Nahum, and therefore there is no need to posit a pre-Lukan redactor as the author of this verse. The author of Luke himself had sufficient motive for adding the notice about the positive response Jesus’ teaching received in Capernaum. He probably did not notice that his insertion divided the pericope into two parallel parts, with Part One being a mere shadow of Part Two.

L26 ἐξεπλήσσοντο (Luke 4:32). The astonishment the synagogue worshippers felt at Jesus’ teaching (Luke 4:32) parallels the shock (θάμβος [thambos]; L59) that came upon everyone when Jesus exorcised the demon (Luke 4:36).

ἐξεπλήσσοντο (Mark 1:22). In Luke the antecedent of the verb ἐξεπλήσσοντο (exeplēssonto, “they were astonished”) is clearly expressed: “they” are the “them” (αὐτούς; L20) Jesus had been teaching (i.e., the people of Capernaum).[102] In Mark the antecedent of ἐξεπλήσσοντο should be the same as the antecedent of the previous third-person plural verb, εἰσπορεύονται (eisporevontai, “they go in”; L1), namely the disciples. But since the disciples play no role in the story, the author of Mark probably meant that it was the people in the synagogue who were astonished. It was the author of Mark’s redactional activity in L19, where “entering the synagogue” replaces Luke’s “them” (see above, Comment to L18-21), that caused the proper antecedent of Mark’s verb in L26 to be erased.

L27 οἱ ὄχλοι (Matt. 7:28). The author of Matthew corrected Mark’s grammar by providing οἱ ὄχλοι (hoi ochloi, “the crowds”) as the missing antecedent.[103] “The crowds” are not appropriate for the synagogue setting of Teaching in Kefar Nahum, but the phrase ties in neatly with the opening of the Sermon on the Mount, where the author of Matthew described the crowds that surrounded Jesus (Matt. 5:1).[104] It is just possible, however, that οἱ ὄχλοι is (also?) the product of cross-pollination with Matt. 22:33 (∥ Mark 11:18), which is really a doublet of Matt. 7:28 ∥ Mark 1:22. According to Matt. 22:33, the crowds in the Temple were astonished at Jesus’ teaching. Since the author of Matthew sometimes allowed the wording of parallel sayings to influence one another, a phenomenon we refer to as Matthean cross-pollination, and since we know from Mark 11:18 that οἱ ὄχλοι appeared in Matthew’s source for Matt. 22:33, it may be that οἱ ὄχλοι crossed over into Matt. 7:28 from Matt. 22:33.

L30 ἐπὶ τῇ διδαχῇ αὐτοῦ (Luke 4:32). Flusser noted that, apart from Luke 4:32 and the parallels in Mark 1:22 and Matt. 7:28, there is never agreement between all three evangelists to use the noun διδαχή (didachē, “teaching”).[105] Matthew agrees with Mark to write διδαχή on one further occasion (Matt. 22:33 ∥ Mark 11:18), which we just discussed in the previous comment. The noun διδαχή occurs three more times in Mark, a second time in Teaching in Kefar Nahum (Mark 1:27 [L65]) and twice in what Flusser referred to as “frame sentences” (Mark 4:2; 12:38). The Lukan-Matthean agreements against these Markan instances of διδαχή indicate that they are the product of Markan redaction.[106] The author of Matthew used the noun διδαχή once on his own in a clearly redactional explanation identifying the “leavened bread of the Pharisees and Sadducees” as the “teaching of the Pharisees and Sadducees” (Matt. 16:12). Since Flusser considered Luke 4:32 to be redactional, he concluded that none of the instances of διδαχή in the Synoptic Gospels can be traced to a pre-synoptic source. We agree.

Flusser also cited the difficulty of reverting the noun διδαχή to Hebrew as an additional reason for regarding Luke 4:32 as redactional.[107] We are not convinced of the strength of this argument. In his Hebrew translation of the New Testament, Delitzsch translated ἐπὶ τῇ διδαχῇ αὐτοῦ (epi tē didachē avtou, “at his teaching”) in Luke 4:32 as עַל תּוֹרָתוֹ (‘al tōrātō, “at his Torah” or “at his teaching”), which is a perfectly legitimate translation. In his Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark, Lindsey adopted the same translation of ἐπὶ τῇ διδαχῇ αὐτοῦ in Mark 1:22.[108] Nevertheless, we might have expected the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua to have translated תּוֹרָה (tōrāh, “Torah”) as νόμος (nomos, “law”), as he probably did in other pericopae.[109] We think an even better reconstruction of ἐπὶ τῇ διδαχῇ αὐτοῦ would be עַל תַּלְמוּדוֹ (‘al talmūdō, “at his teaching”).[110] While it would be fascinating to consider the implications of a pre-synoptic source making reference to Jesus’ Talmud, we agree with Flusser that Luke 4:32 cannot be traced back to the original story of Jesus. For this reason we have omitted ἐπὶ τῇ διδαχῇ αὐτοῦ from GR and a Hebrew equivalent from HR.

L31 ὅτι ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ ἦν ὁ λόγος αὐτοῦ (Luke 4:32). In L31 the author of Luke stresses not what Jesus taught but how it was taught: his word (singular) was spoken “in authority.” It is a little strange that the author of Luke did not write οἱ λόγοι αὐτοῦ (hoi logoi avtou, “his words”), using the plural as he did elsewhere in his Gospel (Luke 1:20; 4:22; 6:47; 9:44; 24:17, 44) and Acts (Acts 2:22; 5:5, 24; 15:15; 16:36; 20:35). Flusser accounted for this peculiarity by suggesting that the reference to Jesus’ authoritative “word” in Luke 4:32 was modeled after Luke 4:36, in which the people asked, “What is this thing [λόγος ⟨sing.⟩], that in authority and power he commands the impure spirits and they go out?”[111]

Apart from Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum, where ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ (en exousia, “in authority”) occurs twice (L31, L66), the phrase ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ is rare in the Synoptic Gospels, occurring only in the question ἐν ποίᾳ ἐξουσίᾳ ταῦτα ποιεῖς (en poia exousia tavta poieis, “By what authority do you do these things?”; Matt. 21:23; Mark 11:28; Luke 20:2), posed to Jesus in the narrative introduction to the Wicked Tenants parable, and in Jesus’ response to this question (Matt. 21:24, 27; Mark 11:29, 33; Luke 20:8). It is true that ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ also occurs twice in Acts (Acts 1:7; 5:4), but only in the early sections of this book, where the author of Luke was most likely to have been following a source. The lack of evidence for the author of Luke’s habitually adding ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ to his sources strengthens our supposition that, like ὁ λόγος, the phrase ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ in Luke 4:32 also derives from Luke 4:36.

L31-32 ἦν γὰρ διδάσκων αὐτοὺς ὡς ἐξουσίαν ἔχων (Mark 1:22). Whereas Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum celebrates the manner of Jesus’ teaching (his word was authoritative), the Markan and Matthean parallels celebrate the force of Jesus’ personality: he was teaching them ὡς ἐξουσίαν ἔχων (hōs exousian echōn, “as one possessing authority”).[112] It is difficult to believe that if he had been reworking Mark’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum the author of Luke would have toned down the laudatory remarks about Jesus’ person, choosing instead to focus on the authority of Jesus’ word. But the reverse scenario is entirely credible. It is easy to imagine the author of Mark preferring to stress Jesus’ authoritative personality over the quality of Jesus’ teaching. And note this: Mark’s phrase ἦν γὰρ διδάσκων αὐτούς (ēn gar didaskōn avtous, “for he was teaching them”) echoes Luke’s wording in L20 (ἦν διδάσκων αὐτούς). The author of Mark copied Luke’s wording, but he inserted it into an explanatory γάρ clause, a type of narrative clause that is especially typical of Markan redaction.[113]

By shifting the emphasis away from Jesus’ teaching and onto Jesus’ personality, the author of Mark eliminated the term λόγος, which, on account of its repetition and awkwardness (the singular form in L31, its ambiguousness in L64), is so conspicuous in Luke’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum. From the perspective of Lindsey’s hypothesis we can understand why the term λόγος in Teaching in Kefar Nahum had lost its significance for the author of Mark. It was precisely the ambiguousness of λόγος in the question τίς ὁ λόγος οὗτος (“What is this logos?”) that allowed the author of Luke to model the people’s response to Jesus’ teaching on their response to the exorcism. By wrongly understanding τίς ὁ λόγος οὗτος as asking, “What is this word?” the author of Luke concluded that Jesus had uttered some magical word of power to exorcise the demon. Therefore, when he composed the people’s reaction to Jesus’ teaching he explained that Jesus’ “word” had authority. But with the addition of Luke 4:32 to the narrative, the meaning of τίς ὁ λόγος οὗτος in Luke 4:36 was no longer ambiguous. Luke 4:32 had prepared the author of Mark to understand λόγος in both verses as meaning “word.” Yet the clarity of λόγος in Luke’s pericope also robbed this term of its interest. It no longer needed to be interpreted and explained, and so became easy to dispense with. For the author of Mark it was more attractive and interesting in L31-32 to attribute authority to Jesus’ person than his word, and in L65 the author of Mark supplied an answer to the question “What is this word?”: the “word” was none other than the “new teaching” born of Jesus’ personal authority (L66). Thus the same process that led to the elimination of λόγος in Mark’s version of Teaching in Kefar Nahum also led to the elimination of the phrase ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ. No longer was Jesus’ word spoken “in authority” (L31), rather Jesus taught “as one having authority” (L31-32), and no longer did Jesus issue commands “in authority” (L66), rather Jesus’ “new teaching” stemmed from his personal authority (L66).

Lindsey noted that Mark’s phrase ἦν γὰρ διδάσκων αὐτοὺς ὡς ἐξουσίαν ἔχων (“for he was teaching them as one possessing authority”) “can be put into Hebrew only by resorting to awkward circumlocution.”[114] Indeed, in his Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark Lindsey rendered ἦν γὰρ διδάσκων αὐτοὺς ὡς ἐξουσίαν ἔχων as כִּי הָיָה מְלַמְּדָם כְּאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר הָרְשׁוּת בְּיָדוֹ (ki hāyāh melamdām ke’ish ’asher hāreshūt beyādō, “because he was teaching them like a man who the authority was in his hand”),[115] which may be compared to Delitzsch’s translation of this phrase as כִּי הָיָה מְלַמְּדָם כְּאִישׁ שִׁלְטוֹן (ki hāyāh melamdām ke’ish shilṭōn, “because he was teaching them like a ruler man,” or alternatively, “because he was teaching them like a man of authority”).

Some scholars have proposed a more elegant reconstruction of “he was teaching them as one possessing authority”: הָיָה מְלַמְּדָם כְּמוֹשֵׁל (hāyāh melamdām kemōshēl, “he was teaching them like a teller of parables”).[116] This reconstruction rests on the supposition that ὡς ἐξουσίαν ἔχων is a mistranslation of כְּמוֹשֵׁל, which can either mean “like a ruler” or “like a teller of meshalim [i.e., proverbs, parables, etc.]”). Making this suggestion attractive are the facts that 1) Jesus did tell parables to illustrate his teaching and 2) the scribes did enjoy considerable authority in Jewish society (cf., e.g., m. Sanh. 11:3),[117] such that Mark’s assertion that Jesus taught as one having authority and not as the scribes is false. Nevertheless, there are serious problems with this reconstruction. First, even if an underlying Hebrew source had referred to Jesus as a מוֹשֵׁל (mōshēl, “teller of parables”), ἐξουσίαν ἔχων (exousian echōn, “one having authority”) is a bizarre translation. Usually when the LXX translators encountered מוֹשֵׁל they rendered it as ἄρχων (archōn, “ruler”)[118] or some other term for “ruler.” Second, that מוֹשֵׁל means “teller of parables” has not been established. We do, indeed, find examples of מוֹשֵׁל in the sense of “teller of proverbs” or “reciter of verses” (Num. 21:27; Ezek. 16:44), but these are confined to Biblical Hebrew. We never find מוֹשֵׁל in the sense of “teller of story parables” in post-biblical Hebrew sources.[119] Third, when the LXX translators encountered מוֹשֵׁל in the sense of “teller of proverbs” they understood its meaning and translated it correctly. So even if we granted for the sake of argument that מוֹשֵׁל could be used in the sense of “teller of parables,” there is no reason why a Greek translator should have misunderstood it. And finally, contrasting “tellers of parables” with the scribes is not really an improvement over the contrast between “one having authority” and the scribes, since, like Jesus, the ancient scribes told parables. Thus this ingenious suggestion does not pose a serious challenge to our view that “he taught them as one having authority” reflects the author of Mark’s rewriting of Luke, which shifts the locus of Jesus’ authority from his teaching to his person and transforms a laudatory statement about Jesus into a polemic against the Jewish authorities.

L32 ἔχων (Mark 1:22). Lindsey hinted that the author of Mark borrowed the phrase ἐξουσίαν ἔχων (exousian echōn, “having authority”) from Luke’s version of the Entrusted Funds parable, where the returning master rewards his most faithful servant saying, ἴσθι ἐξουσίαν ἔχων ἐπάνω δέκα πόλεων (“Be one having authority over ten cities”; Luke 19:17).[120] We think the origin of Mark’s phrase lies closer to hand. Mark’s phrase ἐξουσίαν ἔχων (“[one] having authority”) is similar to Luke’s description in L38-39 of the demoniac as ἄνθρωπος ἔχων πνεῦμα δαιμονίου ἀκαθάρτου (anthrōpos echōn pnevma daimoniou akathartou, “a person having a spirit of an impure demon”; Luke 4:33). Oddly, Mark’s description of the demoniac as ἄνθρωπος ἐν πνεύματι ἀκαθάρτῳ (anthrōpos en pnevmati akathartō, “a person in an impure spirit”; Mark 1:23) resembles the reason Luke gives in L31 for why the people were astonished at Jesus’ teaching: ἐν ἐξουσίᾳ ἦν ὁ λόγος αὐτοῦ (en exousia ēn ho logos avtou, “his word was in authority”; Luke 4:32). In other words, there is an inverse or chiastic relationship between the statements on authority and the descriptions of the demoniac.[121]

L33 καὶ οὐχ ὡς οἱ γραμματεῖς (Mark 1:22). Numerous scholars have asked in what way Jesus’ authoritative teaching contrasted with that of the scribes, and many have answered by referring to the way in which the rabbinic sages cited halachot, testimony and other traditions in the names of their predecessors. Citing the teachings of earlier and more important sages, these scholars claim, is how the scribes taught, whereas Jesus did not need to cite authority for his teaching.[122] We take a dim view not only of this answer but of the question itself. As we have already noted, the contrast between Jesus as “one having authority” and the scribes is a false dichotomy.[123] Mark’s assertion is polemical and cannot be taken at face value.[124] Among first-century Jews the scribes commanded respect and their teachings carried authority.[125] When it is recognized that the claim in Mark 1:22 that Jesus taught “as one having authority and not as the scribes” is not a statement of historical fact but a snippet of polemically charged propaganda, then there is no point in asking in what way the scribes’ teaching lacked authority. There is no point in asking because there is no substance behind the author of Mark’s claim.

Even the answer so many scholars have given to the question “In what way did the scribes lack authority in comparison to Jesus?” is problematic. First, it is anachronistic to attribute the method of citing halachot prevalent among the rabbis of the Mishnah and the Talmud to the scribes of the Second Temple period. Second, it is a mistake to equate the rabbinic sages of the Mishnah and the Talmud with the scribes of the Second Temple period. The fact is, the author of Mark did not explain how the scribes lacked authority, and if asked, he probably could not have done so.[126] He made an unsubstantiated assertion because he wanted to draw a contrast between Jesus and the scribes, who were to feature as Jesus’ main opponents in the stories to follow (Mark 2:6, 16; 3:22). The misleading answer that Jesus differed from the scribes by not citing the names of earlier and more learned rabbis has its roots in later Christian anti-Judaism and should be weeded out from modern discussions about the historical Jesus.

L34 αὐτῶν (Matt. 7:29). To Mark’s reference to οἱ γραμματεῖς (hoi grammateis, “the scribes”) the author of Matthew added the pronoun αὐτῶν (avtōn, “their”).[127] While Mark’s contrast between Jesus and the scribes could still be viewed as an inner-Jewish critique, Matthew’s transformation of “the scribes” into “their scribes” places the author of Matthew and his readers outside the Jewish community.[128] In doing so, the author of Matthew opposes Christianity to Judaism.