How to cite this article:

Joshua N. Tilton and David N. Bivin, “Quieting a Storm,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2022) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/25610/].

Matt. 8:18, 23-27; Mark 4:35-41; Luke 8:22-25[1]

Updated: 4 December 2025

וַיְהִי בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם וַיֵּרֶד לִסְפִינָה הוּא וְתַלְמִידָיו [וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם נַעֲבֹר לְעֵבֶר הַיָּם ⟨וַיַּעַבְרוּ⟩] וְהָיוּ בָּאִים וְהִנֵּה סַעַר גָּדוֹל עָמַד עֲלֵיהֶם בַּיָּם לְטֹבְעָן וְהוּא שָׁכַב בְּיַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה וַיֵּרָדֵם וַיִּקְרְבוּ וַיָּעִירוּ אוֹתוֹ לֵאמֹר אֲדוֹנֵנוּ אֲדוֹנֵנוּ נֹאבֵד וַיֵּעוֹר וַיִּגְעַר בָּרוּחוֹת וּבַמַּיִם וַיָּנַח [הַיָּם ⟨מִזַּעְפּוֹ⟩] וַיְהִי שָׁלוֹם גָּדוֹל וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם הַאֲמִינוּ בֵּאלֹהִים וַיִּירְאוּ הָאֲנָשִׁים יִרְאָה גְדוֹלָה וַיִּתְמְהוּ לֵאמֹר מָה הַדָּבָר הַזֶּה שֶׁהוּא מְצַוֶּה אַף לָרוּחוֹת וְאַף לַמַּיִם וְהֵם שׁוֹמְעִים לוֹ

Sometime around then Yeshua boarded a boat—he and his disciples. [And Yeshua said to them, “Let’s cross over to the opposite shore.” ⟨So they crossed over.⟩] Now as they were sailing, a huge storm overtook them on the lake that was liable to sink them. But Yeshua had lain down at the back of the boat and was sound asleep. So the disciples went to Yeshua and woke him up. “Lord! Lord!” they exclaimed. “We’re all about to die!”

At that, Yeshua woke up and rebuked the blowing winds and splashing waters, whereupon the lake stopped its raging and a profound calm took its place. Then Yeshua said to his disciples, “Trust God!”

Yet the disciples were very much afraid. Looking in awe at one another, they said, “How is it that Yeshua commands the elements and they obey him?”[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Quieting a Storm click on the link below:

| “Power of Faith” complex |

| Quieting a Storm ・ Faith Like a Mustard Seed |

Story Placement

Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm does not give precise information regarding when the events it describes took place, nor even the location from which Jesus and his companions launched the boat in which they crossed the lake.[3] Unlike the Markan and Matthean versions of Quieting a Storm, Luke’s version does not even provide an indication as to the time of day (or night) when Jesus and his companions set sail.

Nevertheless, Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm (Luke 8:22-25) occurs in the same chapter as Luke’s parables excursus (Luke 8:4-18), which is followed by Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers (Luke 8:19-21). The proximity of Quieting a Storm to Luke’s parables excursus is probably what inspired the author of Mark to set Quieting a Storm (Mark 4:35-41) on the same day as Jesus’ delivery of his parables discourse (Mark 4:1-34), all of which takes place in Mark following Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers (Part 2) (Mark 3:31-35).[4] This being the case, we regard Mark’s connection of the events described in Quieting a Storm to the events described in Mark’s parables discourse as entirely artificial.[5] The Markan placement of Quieting a Storm on the same day as Jesus’ delivery of a parables discourse is a literary construct, not a historical recollection.

Perhaps because the author of Matthew did not find Quieting a Storm connected to a parables discourse in the Anthology (Anth.), he felt free to relate these events in a context different from Mark’s. In Matthew, Quieting a Storm takes place on the same day as Centurion’s Slave (Matt. 8:5-13), Shimon’s Mother-in-law (Matt. 8:14-15) and Healings and Exorcisms (Matt. 8:16-17), all of which are presented as having taken place in Capernaum. As was the case in Mark, the Matthean setting of Quieting a Storm is also artificial. The author of Matthew combined events his sources indicated had taken place in Capernaum and presented them as having occurred on a single day. Matthew’s “day in Capernaum” is likewise a literary construct, not a historical recollection.

Into the framework of Quieting a Storm the author of Matthew inserted his version of Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple (Matt. 8:19-22).[6] Thus, in Matthew’s Gospel, Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, like the previous events in Matthew 8, takes place in or near Capernaum. In Luke’s version of Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, by contrast, there is no Capernaum connection. Splicing one episode or saying into another pericope occurs in all three Gospels,[7] and it is often an indication of redactional activity.

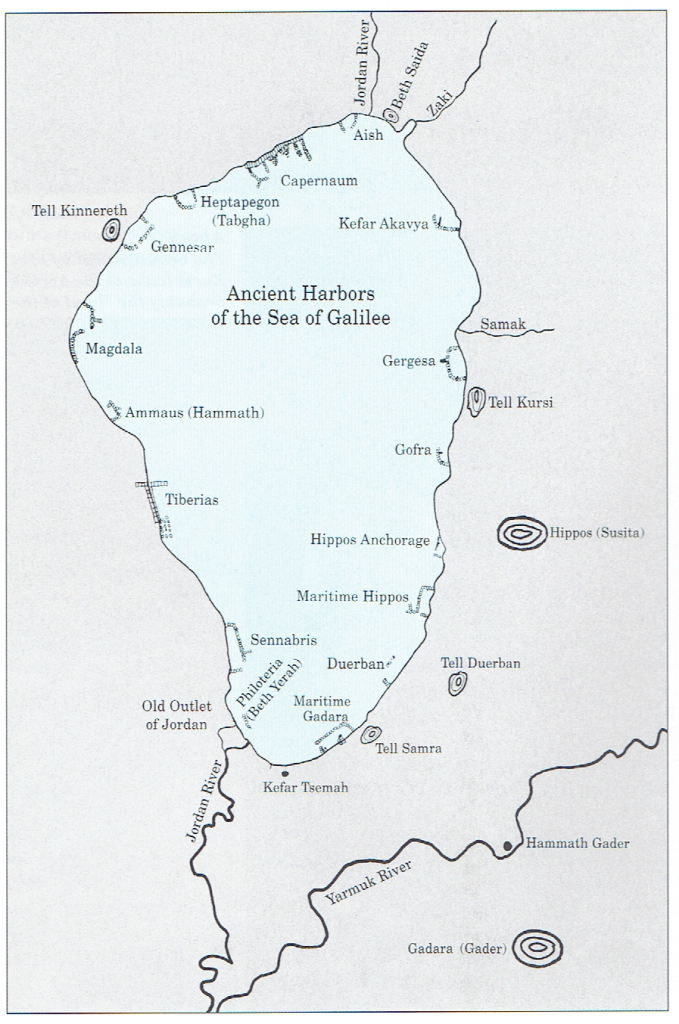

Having concluded that the placements of Quieting a Storm in Mark and Matthew are secondary, and given the fact that Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm supplies no detailed information regarding chronology or location, all that can be surmised is that the event took place during the Galilean stage of Jesus’ ministry sometime after Jesus had acquired a following of disciples. If the placement of Possessed Man in Girgashite Territory as the sequel to Quieting a Storm in all three Synoptic Gospels preserves a historical reminiscence, then Jesus and his companions must have launched their boat somewhere on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, since their destination lay on the eastern shore of the lake. There are no stories of Jesus having visited Tiberias or any village on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee south of that city, so a starting point at Magdala, Capernaum or any of the villages that lay between is probable.

We have placed Quieting a Storm close to the end of the Galilean stage of Jesus’ ministry on the assumption that Jesus must have resumed itinerating with his disciples following the mission of the twelve apostles. The high expectations Jesus has of his companions in Quieting a Storm implies an advanced stage of discipleship appropriate for the post-apostolic mission period. Perhaps news of John the Baptist’s execution was the occasion for Jesus’ withdrawal from the tetrarchy of Herod Antipas.

For reasons we will discuss in Faith Like a Mustard Seed, we believe Quieting a Storm may once have belonged to a larger literary unit consisting not only of a narrative incident, but continuing with a certain amount of teaching material. For an overview of how this larger literary unit, which we call the “Power of Faith” complex, may have been shaped, click here.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

Adherents to the Two-source Hypothesis must assume that both the Lukan and Matthean versions of Quieting a Storm are independently based upon Mark’s. However, those who subscribe to Robert Lindsey’s solution to the Synoptic Problem, which posits that Luke’s Gospel is a source for Mark’s, and Mark’s Gospel is a source for Matthew’s, cannot help but notice that of the three versions of Quieting a Storm Luke’s version is the most coherent. According to Luke’s account, Jesus and his disciples are caught in a storm while crossing the Sea of Galilee by boat. Jesus, who had fallen asleep, is wakened by the disciples, who inform him that they are in mortal danger.[8] Instead of being frightened, Jesus rebukes the elements, asks the disciples what has become of their faith, and the astonished disciples wonder how Jesus is able to command the forces of nature. Mark’s version is different. According to Mark, when the disciples are frightened by the storm, they awake Jesus with an accusatory question: “Don’t you care that we are going to die?” The question presupposes both that Jesus was aware of the present danger and that he was able to do something about it. But since Jesus had been sleeping, the presumption that he was aware of their peril is illogical.[9] Just as illogical in Mark is the disciples’ amazement at Jesus’ ability to command the storm to cease, since their question presupposes their belief that he was able to do just that. Why should they be astonished when Jesus did precisely what they expected him to do? Matthew’s version of Quieting a Storm suffers from a similar inconsistency. Fearing for their lives, the disciples wake Jesus with the prayer “Lord! Save us!” It is obvious from their petition that they believed Jesus was able to deliver them from their dangerous predicament. But Jesus responds to the disciples’ plea by rebuking them for having little faith. Yet how can the disciples’ faith have been deficient when they fully expected Jesus to save them?

The Two-source Hypothesis also struggles to explain (or explain away) the numerous Lukan-Matthean “minor agreements” against Mark in this pericope. Taken individually, the various explanations Markan priorists offer for how the authors of Matthew and Luke independently made identical changes to Mark’s version of Quieting a Storm seem plausible. But the sheer number of “minor agreements” in Quieting a Storm is staggering. It boggles the mind to assume that two independent authors would have made so many of the same “corrections” to Mark’s story. The Lukan-Matthean “minor agreements” against Mark can be grouped into two classes: positive agreements of wording and negative agreements of omission.

Positive Lukan-Matthean agreements against Mark in Quieting a Storm include:

- L1: δέ in Matthew and Luke vs. καί in Mark

- L9: ἐμβαίνειν in Matthew and Luke vs. παραλαμβάνειν in Mark

- L11: εἰς [τὸ] πλοῖον in Matthew and Luke vs. ἐν τῷ πλοίῳ in Mark

- L13: οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ in Matthew and Luke vs. the absence of a direct reference to the disciples in Mark

- L22: preposition + definite article + noun for body of water in Matthew and Luke vs. the absence of a reference to the body of water in Mark

- L31: προσελθόντες in Matthew and Luke vs. the absence of anyone “approaching” Jesus in Mark

- L33: λέγοντες in Matthew and Luke vs. καὶ λέγουσιν αὐτῷ in Mark

- L34: use of a title indicating mastery in Matthew (κύριε) and Luke (ἐπιστάτα) vs. “teacher” in Mark

- L53: ἐθαύμασαν λέγοντες in Matthew and Luke vs. καὶ ἔλεγον in Mark

- L58: ὑπακούουσιν in Matthew and Luke vs. ὑπακούει in Mark

Negative Lukan-Matthean agreements against Mark in Quieting a Storm include:

- Omission of evening (ὀψίας γενομένης) in L3

- Omission of “leaving” (καὶ ἀφέντες) the crowd in L8

- Omission of Jesus’ prior locality in the boat (ὡς ἦν) in L10

- Omission of other boats accompanying Jesus in L12-13

- Omission of Jesus’ lying in the stern on a pillow in L28-29

- Omission of a question addressed to Jesus in L35-36

- Omission of an equivalent to “he said” (εἶπεν) in L42

- Omission of direct speech (σιώπα πεφείμωσο) in L43

- Omission of a reference to the wind in L44

- Omission of “big fear” (φόβον μέγαν) in L52

Agreements of omission are, admittedly, less weighty as evidence that the authors of Matthew and Luke each made use of a non-Markan version of Quieting a Storm, since two authors who sought to pare down the wording of their source might well select the same items for deletion, but two authors agreeing to use the same (or nearly the same) wording at precisely the same points while independently reworking Mark’s text strains credulity.[10] The Lukan-Matthean agreements against Mark in Quieting a Storm are hardly negligible and demand a more satisfactory explanation than mere chance.[11]

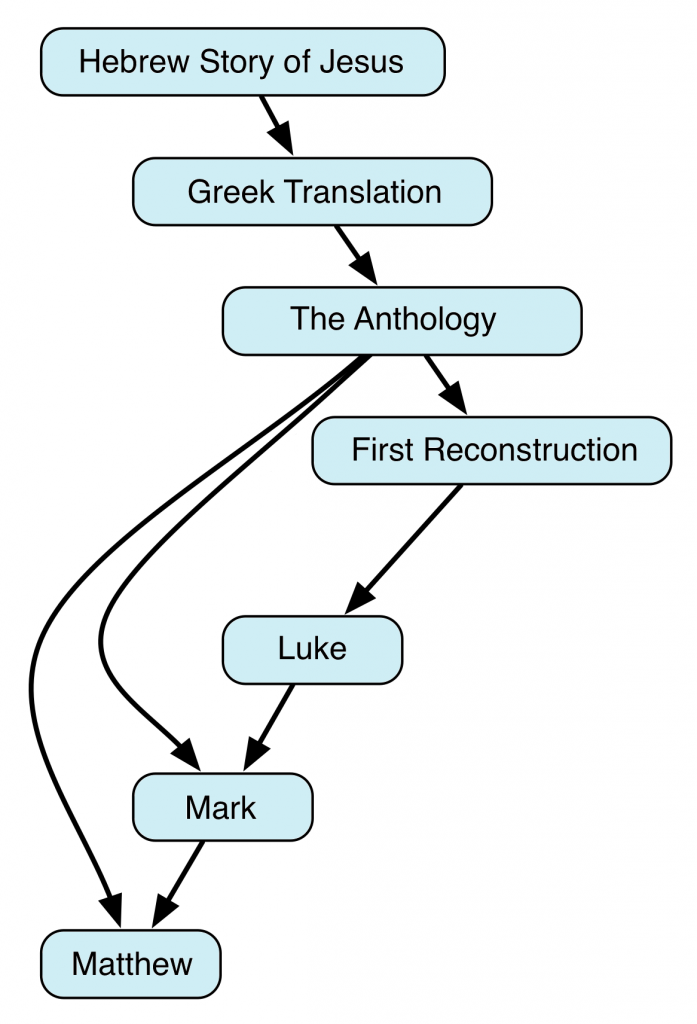

It is far more credible that most of the Lukan-Matthean minor agreements against Mark reflect the use of a non-Markan source by the authors of Luke and Matthew. Luke, which according to Lindsey was composed prior to Mark, is entirely free of Markan influence. Matthew, which according to Lindsey is the latest of the Synoptic Gospels, combines Mark’s wording with that of a pre-synoptic source. Luke and Matthew agree against Mark whenever the author of Matthew preferred the wording of his non-Markan source to Mark’s and the author of Luke reproduced the wording of his pre-synoptic source.

The explanation Lindsey’s hypothesis offers for the Lukan-Matthean agreements against Mark in Quieting a Storm is that these verbal agreements ultimately originated from the same pre-synoptic source, a source Lindsey called the Anthology (Anth.). For Quieting a Storm the author of Luke made use of a redacted version of Anth.’s account from a parallel source Lindsey called the First Reconstruction (FR). The author of Matthew blended the wording of Mark’s version of Quieting a Storm with Anth.’s. The “minor agreements” between Matthew and Luke were achieved whenever two conditions converged: 1) when the author of Matthew preferred Anth.’s wording to Mark’s and 2) when Luke’s source (FR) retained the wording of Anth. When these two conditions were met, the authors of Matthew and Luke agreed, not by chance, but on account of literary dependence on non-Markan sources.

What are the reasons for supposing the author of Luke copied Quieting a Storm from FR rather than directly from Anth.? First, we have found that the pericopae preceding Quieting a Storm in Luke 8 were copied from FR,[12] and since the author of Luke tended to copy large sections from his sources rather than alternating between sources for every other story, FR is a likely candidate as the source behind Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm. Second, portions of Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm, particularly at the opening of the narrative, are difficult to reconstruct in Hebrew. Resistance to Hebrew retroversion is more typical of pericopae the author of Luke copied from FR than of those copied from Anth., since it was the First Reconstructor’s method to polish Anth.’s Hebraic-Greek style. Third, Quieting a Storm contains vocabulary (e.g., ἐν μιᾷ τῶν ἡμερῶν, L2; διέρχεσθαι, L15; λίμνη, L16, L22; ἐπιστάτης, L34) typical of pericopae copied from FR (see below, Comment to L2, Comment to L15 and Comment to L34). These three reasons explain our conclusion that the author of Luke copied Quieting a Storm from FR.

Crucial Issues

- Is Quieting a Storm a kind of exorcism narrative?

- How would first-century readers understand Quieting a Storm’s significance?

Comment

L1 καὶ λέγει αὐτοῖς (Mark 4:35). In numerous ways the author of Mark sought to tie his version of Quieting a Storm to the parables discourse that precedes it. One strategy he used to achieve this goal was to use pronouns to refer to the main characters (Jesus and the disciples) rather than calling them by name.[13] As a result, readers had to refer back to Mark 4:34 to identify the “them” in L1 as the disciples,[14] and all the way back to Mark 3:7, well before the parables discourse, to identify the speaker as Jesus. The effect of using pronouns is to give the impression of continuity between one pericope and the next.

Nevertheless, the author of Mark’s use of the historical present (λέγει [legei, “he says”]) in L1 is un-Hebraic, especially in comparison to the ἐγένετο δὲ + temporal marker + finite verb construction with which Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm opens. Since the use of the historical present is typical of Markan redaction,[15] we can safely attribute Mark’s wording in L1 to the author of Mark’s editorial activity rather than to his non-Lukan source.[16]

ἰδὼν δὲ ὁ Ἰησοῦς (Matt. 8:18). Matthew’s description of Jesus seeing the crowds likewise creates continuity between Quieting a Storm and that which went before. In Matthew’s case, Healings and Exorcisms (Matt. 8:16-17) precedes the introduction to Quieting a Storm (Matt. 8:18). Since a link between Healings and Exorcisms and Quieting a Storm exists only in Matthew’s Gospel, the connection is more likely to be a literary construct of the author of Matthew’s making than a historical recollection. This conclusion has led to our rejection of Matthew’s wording in L1 for GR.

καὶ ἐγένετο (GR). Simply because we rejected Mark’s and Matthew’s introductions to Quieting a Storm we cannot automatically accept Luke’s wording for GR. This is especially the case in pericopae the author of Luke copied from FR, since there is no guarantee that the First Reconstructor preserved the wording of Anth.

In the present case, however, the construction with which Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm opens (ἐγένετο δὲ + time marker + finite verb) is highly Hebraic,[17] as we have already noted. It therefore seems likely that Luke’s opening is based on something that appeared in Anth., even if that something has been slightly altered in the course of transmission. Even more Hebraic than ἐγένετο δὲ + time marker + finite verb would be καὶ ἐγένετο + time marker + finite verb, and it may be that this is one case where the Lukan-Matthean “minor agreement” against Mark to write δέ (de, “but”) instead of Mark’s καί (kai, “and”) is merely a coincidence, the result of two redactors (Matthew and FR) improving the Greek of their respective sources (Mark in the case of Matthew; Anth. in the case of FR). Thus, we have adopted a slightly modified version of Luke’s wording in L1 for GR.

L2 ἐν ἐκείναις ταῖς ἡμέραις (GR). As in L1, so in L2 we have adopted a slightly modified version of Luke’s wording for GR. Luke’s phrase ἐν μιᾷ τῶν ἡμερῶν (en mia tōn hēmerōn, “in one of the days”) never occurs in LXX,[18] and although this phrase could be reconstructed as בְּאַחַד הַיָּמִים (be’aḥad hayāmim, “in one of the days”), no such phrase occurs as the introduction to a story in MT, DSS or early rabbinic sources. But while “in one of the days” may be unheard of in Hebrew, בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם (bayāmim hāhēm, “in those days”) is attested in MT at the opening of narratives.[19] The LXX translators typically rendered בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם as ἐν ταῖς ἡμέραις ἐκείναις (en tais hēmerais ekeinais, “in those days”).[20] We might, therefore, regard ἐν μιᾷ τῶν ἡμερῶν in Luke 8:22 as a paraphrase of ἐν ἐκείναις ταῖς ἡμέραις in Anth. Mark’s ἐν ἐκείνῃ τῇ ἡμέρᾳ (en ekeinē tē hēmera, “in that day”) could then be seen as, inter alia, an attempt to reconcile Anth.’s plural phrase “in those days” with Luke’s singular phrase “in one of the days.” Of course, the author of Mark was also interested in synchronizing Quieting a Storm with his earlier parables discourse, so we cannot rely too heavily on Mark’s testimony. In any case, we believe ἐν ἐκείναις ταῖς ἡμέραις is a good option for GR. We adopted precisely this phrase for GR in Yerushalayim Besieged, L33.

The temporal phrase ἐν μιᾷ τῶν ἡμερῶν also occurs elsewhere in Luke (Luke 5:17; 20:1), but it never appears in Mark or Matthew. We have yet to determine whether the other pericopae in which ἐν μιᾷ τῶν ἡμερῶν occurs are derived from Anth. or FR, so we cannot say whether ἐν μιᾷ τῶν ἡμερῶν is characteristic of Lukan redaction or the vocabulary of FR. However, the fact that the phrase ἐν μιᾷ τῶν ἡμερῶν never occurs in the book of Acts hints that it may be the First Reconstructor who is responsible for ἐν μιᾷ τῶν ἡμερῶν in Luke.

בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם (HR). On reconstructing ἡμέρα (hēmera, “day”) with יוֹם (yōm, “day”), see Choosing the Twelve, Comment to L1.

L3 ὀψίας γενομένης (Mark 4:35). Mark’s version of Quieting a Storm opens with two time markers: “on that day” in L2 and “at evening” in L3. The author of Mark undoubtedly added the second time marker in order for his placement of Quieting a Storm on the same day as the parables discourse to make sense. The author of Mark depicts the events described in Quieting a Storm as taking place late in the day after Jesus had spoken to the crowds in parables.[21] There may be an additional reason that motivated the author of Mark to add “at evening,” however. The timing of the narrative late in the day goes some way toward explaining how Jesus could have slept through the raging storm.[22] The author of Mark’s explanation was that the storm overtook the seafarers at the normal time for sleeping.

Two considerations strengthen our supposition that Mark’s temporal phrase in L3 is redactional.[23] First, the time marker is expressed with a genitive absolute construction. Genitives absolute are un-Hebraic; as a consequence, they rarely appeared in Anth. On the other hand, the insertion of genitive absolute constructions is characteristic of Markan redaction. All genitive absolute constructions in Mark must therefore be eyed with suspicion. Second, genitives absolute involving ὀψία (opsia, “latter part of the day,” “evening”) are particularly Markan.[24] Four of Matthew’s seven instances of a genitive absolute phrase including the time marker ὀψία are taken over from Mark (Matt. 8:16 [= Mark 1:32]; 14:23 [= Mark 6:47]; 26:20 [= Mark 14:17]; 27:57 [= Mark 15:42]). Genitive absolute phrases including ὀψία never occur in Luke and are unlikely to have occurred in Anth. on account of their un-Hebraic quality. Thus, it is likely that all six of Mark’s instances of genitive absolute involving ὀψία are redactional.

While Mark’s setting of Quieting a Storm at evening helps explain how this story could have taken place on the same day as Jesus’ parables discourse, it creates a difficulty in his overall narrative.[25] If Quieting a Storm took place at evening, at what time did Jesus reach the opposite shore? According to all three Synoptic Gospels, when Jesus reached the shore he encountered a man (or men) afflicted by demons. Jesus drove the demons out, and the people nearby asked Jesus to leave, whereupon Jesus crossed the lake once more. Could all of this have happened on the same evening? It seems unlikely. To resolve this difficulty some scholars have proposed that Jesus and his companions spent the entire night crossing the lake and that the author of Mark simply failed to note that the events described in Possessed Man in Girgashite Territory took place on the following morning.[26] But an all-night boat trip to cross the lake, which at its broadest is only eight miles wide, seems excessive. It is true that we do not know Jesus’ starting point (see the Story Placement discussion above) nor the exact time of Jesus’ departure according to Mark’s chronology, but according to one ancient testimony it took only two hours to cross the lake by boat.[27] Therefore, the suggestion that it took Jesus and the disciples all night to cross the lake—were they rowing around in circles for hours on end?—beggars belief.[28]

This chronological difficulty does not exist in Luke’s Gospel, since the Lukan version of Quieting a Storm does not include a reference to evening. In Matthew’s version of Quieting a Storm ὀψίας γενομένης is missing, too, but the author of Matthew could afford to omit this time marker because he had already signaled the late hour in his version of Healings and Exorcisms (Matt. 8:16) (see above, Comment to L1).

L4 ὄχλον περὶ αὐτὸν (Matt. 8:18). According to Matthew, it was the presence of the many persons seeking to be healed that prompted Jesus to depart (see above, Comment to L1). However, the term ὄχλος (ochlos, “crowd”) does not occur in any synoptic version of Healings and Exorcisms (Matt. 8:16-17; Mark 1:32-34; Luke 4:40-41). The author of Matthew evidently picked up ὄχλος from Mark 4:36 (L8). It is unlikely, therefore, that Matthew’s wording in L4 was taken from Anth. We have accordingly omitted the contents of L4 from GR and HR.

L5-6 διέλθωμεν εἰς τὸ πέραν (Mark 4:35). In Mark’s version of Quieting a Storm it is Jesus’ command that sets the action in motion. In Luke, on the other hand, Jesus and the disciples board the boat before Jesus indicates his desired destination. Either sequence is credible, so it is difficult to decide which sequence is more original. As we will discuss below (see Comment to L19), the First Reconstructor was not averse to rearranging details if he felt doing so made for a smoother, more logical presentation. Therefore, it is not impossible to suppose that the First Reconstructor transposed the order of events by placing the embarkation ahead of Jesus’ command. But it is hard to see how doing so would have been a literary improvement, and Luke’s Greek in L14-16, where Jesus issues the command, reverts reasonably well to Hebrew (see below). We have, therefore, adopted the Lukan order of events for GR and HR.

ἐκέλευσεν ἀπελθεῖν εἰς τὸ πέραν (Matt. 8:18). The author of Matthew converted the direct speech recorded in Mark 4:35 into narrative. That this conversion is redactional, and not a reflection of Anth., is suggested by the author of Matthew’s use of the verb κελεύειν (kelevein, “to command”) in L5. In the Synoptic Gospels κελεύειν is almost entirely concentrated in Matthew, occurring 7xx in Matthew, 0xx in Mark, and only 1x in Luke.[29] It is unlikely that the author of Luke would have avoided κελεύειν had it occurred in his source(s), however, for although κελεύειν appears only once in Luke’s Gospel, this verb occurs seventeen times in Acts (Acts 4:15; 5:34; 8:38; 12:19; 16:22; 21:33, 34; 22:24, 30; 23:3, 10, 35; 25:6, 17, 21, 23; 27:43).[30] All of this suggests that κελεύειν is usually, if not always, redactional in Matthew. We therefore conclude that in L5-6 the author of Matthew was paraphrasing Mark rather than copying Anth.[31]

L7 Having described how Jesus gave an order to depart for the opposite shore of the lake, the author of Matthew interrupted the progression of Quieting a Storm by inserting into it his version of Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple.[32] This insertion of Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple into Quieting a Storm is a literary construct created by the author of Matthew. It is not a historical reminiscence of the day on which Quieting a Storm took place. Thus, France’s suggestion that the limited capacity of the boat into which Jesus was about to embark was the (or a) reason why Jesus turned away the prospective disciples mentioned in Matt. 8:19-22[33] is certainly not correct.

L8 καὶ ἀφέντες τὸν ὄχλον (Mark 4:36). Writing “and leaving the crowd” is one of the ways the author of Mark tied his version of Quieting a Storm to the preceding parables discourse.[34] The crowd is the same as that mentioned in Mark 4:1, whose gathering had forced Jesus to enter the boat. Moreover, as Gundry noted, in Mark 4:36 it is only the disciples who do the “leaving” (L8) and “taking” (L9); Jesus was already located in the boat.[35]

On the redactional character of Mark’s setting of the parables discourse, see Four Soils Parable, Comment to L4-5, 11-17.

L9 παραλαμβάνουσιν αὐτὸν (Mark 4:36). Whereas in Matthew and Luke Jesus actively boards the boat, in Mark Jesus is passively taken along in the boat by the disciples. Jesus’ passivity in Mark 4:36 foreshadows Jesus’ sleep in Mark 4:38.[36]

καὶ ἐνέβη (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark to describe Jesus’ embarkation using the verb ἐμβαίνειν (embainein, “to embark”) strongly suggests that some such description appeared in Anth. Nevertheless, both Luke’s wording and Matthew’s resist Hebrew retroversion. Luke’s wording defies normal Hebrew word order, while Matthew’s dative absolute construction has no Hebrew counterpart. It is likely, therefore, that both authors (or perhaps the First Reconstructor in Luke’s case) paraphrased Anth.’s description rather than copying it exactly. While Luke’s pronoun αὐτός (avtos, “he”) is out of Hebrew word order in L9, αὐτός would fit perfectly in L13 (see below), so perhaps the First Reconstructor moved αὐτός from there to a more emphatic position in L9. GR in L9 and L13 reflects this supposition.

וַיֵּרֶד (HR). Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew expressed “embark” with the verb יָרַד (yārad, “descend”), as the following examples illustrate:

וַיָּקָם יוֹנָה לִבְרֹחַ תַּרְשִׁישָׁה מִלִּפְנֵי יי וַיֵּרֶד יָפוֹ וַיִּמְצָא אָנִיָּה בָּאָה תַרְשִׁישׁ וַיִּתֵּן שְׂכָרָהּ וַיֵּרֶד בָּהּ לָבוֹא עִמָּהֶם תַּרְשִׁישָׁה מִלִּפְנֵי יי

And Jonah arose to flee to Tarshish from before the LORD, and he went down to Jaffa and found a boat bound for Tarshish. And he paid the fare and embarked [וַיֵּרֶד; LXX: καὶ ἐνέβη] upon it to sail with them to Tarshish from before the LORD. (Jonah 1:3)

טיטוס הרשע נכנס לבית קדש הקדשים וחרבו שלופה בידו וגידד שתי פרכות ונטל שתי זונות והציע ספר תורה תחתיהן ובעלן על גבי המזבח ויצאת חרבו מליאה דם. מן דאמ′ מדם הקדשים ומן דאמ′ מדם שעיר שליום הכיפורים. התחיל מחרף ומגדף כלפי למעלה…מה עשה כינס כל כלי בית המקדש ונתנן לתוך גרגותני אחת וירד לו לספינה….

Titus the wicked entered the Holy of Holies, and his drawn sword was in his hand, and he cut the two curtains. And he took two prostitutes, and he spread out a Torah scroll under them and had sexual relations with them on the altar, and his sword came out full of blood. There are some who say it was from the blood of the sacrifices, and there are some who say[37] it was from the blood of the goat for the Day of Atonement. He began reviling and blaspheming concerning the Exalted One…. What did he do [next]? He gathered all the Temple’s vessels and he put them in a single net and he embarked on a boat [וְיָרַד לוֹ לִסְפִינָה]…. (Lev. Rab. 22:3 [ed. Margulies, 2:499-500])

Jesus’ embarkation is the first of several parallels between Quieting a Storm and the story of Jonah’s sea voyage.[38] Like Jonah, Jesus boards a boat. Like Jonah, Jesus sleeps through a storm. Like Jonah, Jesus is awakened by fellow passengers. And as in Jonah, the people aboard the boat are filled with awe when the storm abates.[39]

Is there some great theological significance to the parallels between Quieting a Storm and the story of Jonah? And does the similarity to the story of Jonah call the veracity of Quieting a Storm into question? One way to arrive at an answer to these questions is to compare Quieting a Storm to other stories in ancient Jewish literature that are modeled on Jonah’s high-sea adventure. The first concerns the miracle associated with the doors that Nicanor donated to the Temple:

מהו נס שנעשה בהן אמרו כשהיה ניקנור מביאם מאלכסנדריא של מצרים עמד עליהן נחשול שבים לטבען ונטלו אחד מהן והטילוהו לים ובקשו להטיל את השני ולא הניחן ניקנור אמ′ להם אם אתם מטילין את השיני הטילוני עמו היה מצטער ובא עד שהגיע לנמילה של יפו כיון שהגיעו לנמילה של יפו היה מבעבע ועולה מתחת הספינה ויש אומ′ אחת מן חיה שבים בלעה אותו וכיון שהגיע ניקנור לנמילה של יפו פלטתו והטילתו ליבשה

What was the miracle that was done for them [i.e., Nicanor’s doors]? They said that when Nicanor was bringing them from Alexandria in Egypt a gale of the sea [נחשול שבים; Yerushalmi: סַעַר גָּדוֹל (“a great storm”)] rose against them to sink them. And they took one of them and threw it into the sea. And they sought to throw in the second, but Nicanor did not permit them. He said to them, “If you throw in the second, throw me in with it. He was remorseful, but they went until they reached the harbor of Jaffa. As soon as they reached the harbor of Jaffa it was bubbling and it came up from under the boat. And there are those who say one of the beasts of the sea swallowed it, and as soon as Nicanor arrived at the harbor of Jaffa it vomited it and threw it on dry land. (t. Yom. 2:4; Vienna MS; cf. y. Yom. 3:6 [19a-b]; b. Yom. 38a)

Features the story of Nicanor and the story of Jonah have in common are life-threatening storms, the tossing overboard of cargo, the request of the protagonist to be thrown into the sea, the miraculous recovery of what was thrown overboard when a sea creature vomits it onto dry land, and the location of Jaffa. Undoubtedly, the story of Nicanor’s doors was modeled on the story of Jonah, but there does not appear to have been a theological motivation for doing so. The point of the Nicanor story is not to suggest that Nicanor was a second, greater Jonah, as some scholars claim is the point of the parallels between Jonah’s story and Quieting a Storm.[40] Nor can we safely conclude from the fact that Nicanor’s story was crafted in such a way as to bring out the similarities with the Jonah story that the story of Nicanor’s doors is entirely fictitious. Certainly the sea monster is an embellishment, and likewise Nicanor’s melodramatic demand to be thrown into the sea along with the second door is suspicious, but the overall scenario in which one of Nicanor’s doors was lost overboard in a storm only to be washed up on land is credible. Only hyper-skepticism demands that the story be dismissed out of hand.

Let us examine another ancient Jewish tale crafted to echo the story of Jonah:

מעשה בתינוק אחד שהיו באין בספינה ועמד עליהן נחשול בים והיו צועקין לאלוהן כעניין שנ’ ויראו המלחים ויצעקו איש אל אלהיו אמ′ להן אותו תינוק עם מתי אתם נשטין זעקו למי שברא הים

An anecdote concerning a certain child. They were sailing in a boat and a gale [נַחְשׁוֹל; Yerushalmi: סַעַר גָּדוֹל (“a great storm”)] arose against them in the sea, and they were crying out to their Canaanite gods, as it is said, And the sailors were afraid and they called out, each to his god [Jonah 1:5]. That child said to them, “How long [Erfurt MS: עַד מָתַי] are you going to be foolish? Cry out to the One who created the sea!” (t. Nid. 5:17; Vienna MS; cf. y. Ber. 9:1 [63b])

This story is not only crafted in such a way as to bring out the similarities to Jonah, it explicitly compares the Gentile seafarers (Phoenician traders from Tyre or Sidon?)[41] to the mariners in the Jonah story. Both groups of sailors cried out to their gods without effect, and, like Jonah, who declared in the midst of the storm, “I fear the LORD who made the sea and the dry land” (Jonah 1:9), the youth declared his faith in the One who created the sea. But are we justified in concluding that the story of the youth on the ship is pure fantasy simply because it has these traits in common with Jonah? We think not. There is no reason why a precocious Jewish youth could not seize the opportunity afforded by the storm to extol the virtues of his religion to the panic-stricken passengers. And is there any particular theological agenda driving the comparison between the Jewish youth and the prophet Jonah? Apparently not. The motive appears to be literary rather than theological. The tradents who passed on the stories of the youth at sea and Nicanor’s doors enjoyed framing them with scriptural motifs and images. Noting the similarities and differences between these stories and the scriptural accounts brought enjoyment to the listeners and storytellers alike.[42]

Likewise, in the case of Quieting a Storm, the points of contact with the story of Jonah neither have a theological agenda nor do they undermine the basic historicity of the account. There is nothing implausible about Jesus and his disciples being caught in a storm while crossing the Sea of Galilee. Neither is it unlikely that whereas the disciples were stricken with panic, Jesus demonstrated extraordinary faith in the face of the storm.[43] If it be granted that miracles are possible, then there is no reason why Jesus could not have quelled the storm. The points of contact with the story of Jonah (boarding the boat, sleeping through a storm, being wakened by fellow passengers) were not included in the narrative for the sake of some theological agenda (e.g., to prove that “a greater than Jonah is here”). Rather, these similarities were highlighted for aesthetic reasons. The audience’s familiarity with the Jonah story kept them in suspense as they waited to see whether things would turn out for Jesus the same as or differently than they had for Jonah.

L10 ὡς ἦν (Mark 4:36). The author of Mark’s addition of “as he was” in L10 is simply a reminder to his audience that Jesus was already in the boat, where he had been since he began teaching the crowds (Mark 4:1).[44] This reminder creates continuity between the parables discourse and Quieting a Storm,[45] but the continuity is literary rather than historical. There is no connection between these events in Luke or Matthew. The link is the author of Mark’s invention. As such, it has been excluded from GR and HR.

L11 εἰς πλοῖον (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreement to write εἰς (eis, “into”) instead of Mark’s ἐν (en, “in”) commends the adoption of their preposition for GR. Moreover, the phrase ἐν τῷ πλοίῳ (en tō ploiō) is indicative of Markan redaction.[46] While in Codex Vaticanus “boat” lacks a definite article in both Luke and Matthew, critical editions read εἰς τὸ πλοῖον (eis to ploion, “into the boat”) in Matt. 8:23, so it is not clear that the omission of the definite article is a true “minor agreement” against Mark. In any case, we have omitted the definite article from GR.

לִסְפִינָה (HR). We considered several options for reconstructing πλοῖον (ploion, “ship,” “boat”). In LXX πλοῖον usually occurs as the translation of אֳנִיָּה (’oniyāh, “ship,” “boat”), but אֳנִיָּה had become obsolete in Mishnaic Hebrew. It is true that we prefer to reconstruct narrative in a biblicizing style of Hebrew, but it may have sounded strange to first-century readers to hear of Jesus sailing in an אֳנִיָּה. The archaic word might have given the impression that Jesus put out in an antique vessel. In his Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark, Lindsey translated πλοῖον in Mark’s version of Quieting a Storm as סִירָה (sirāh, “small boat”),[47] but סִירָה is a Modern Hebrew term that did not have the meaning “boat” in Biblical or Mishnaic Hebrew[48] and is therefore not a viable option for HR. One reconstruction Lindsey rejected is דּוּגִית (dūgit), a term for a type of fishing boat in Mishnaic Hebrew. Lindsey rejected this reconstruction on the grounds that a דּוּגִית, with a capacity for only two or three passengers, is too small to have carried Jesus and his disciples.[49] The word used for “boat” in the stories of Nicanor’s doors and the precocious Jewish youth is סְפִינָה (sefināh). The advantages to reconstructing πλοῖον with סְפִינָה are twofold: it is a term that was still in use in the first century, and the only occurrence of סְפִינָה in the Hebrew Scriptures is in the story of Jonah,[50] so reconstructing πλοῖον with סְפִינָה does not obscure the connection between Quieting a Storm and the Jonah story.

While סְפִינָה is a term for ships that plied the Mediterranean Sea, סְפִינָה was also used for boats that floated up and down the Jordan River (b. Shab. 83b), so סְפִינָה is a term that could easily be applied to craft that traversed the Lake of Gennesar.

In 1986 a boat was discovered on the shore of the lake near Magdala that dates to the first century C.E. When the boat was still in use it had a mast and a sail, it measured about 29 feet long, 8 feet across, and 4 feet deep,[51] and was able to carry fifteen or more adults.[52] The boat, which had a deck in the stern, was typical of boats used by fishermen who fished with seine nets.[53] A boat such as this is probably what is referred to in Quieting a Storm.[54]

L12-13 καὶ ἄλλα πλοῖα ἦν μετ᾽ αὐτοῦ (Mark 4:36). Mark’s statement that other boats accompanied Jesus raises questions for which the author of Mark provides no answers. Were these boats lost in the storm? Did they benefit from the miraculous calming of the wind and water? Why are they not mentioned when Jesus reaches the other side? Some scholars take this irrelevant detail as evidence that the author of Mark reported a historical recollection of an eyewitness,[55] while other scholars more soberly maintain that the reference to other boats is a verbal relic taken over from Mark’s source that no longer makes sense because of the author of Mark’s editorial activity.[56] Yet other scholars have suggested that the author of Mark added the notice about the other boats in order to show what measures Jesus was forced to take to get away from the crowds,[57] or to show that Jesus’ following had increased substantially, so that one boat was not big enough to carry all of them.[58]

The absence of a reference to other boats in Luke and Matthew suggests that additional boats accompanying Jesus were not mentioned in Anth., and yet this evidence is not as strong as it might be, since the author of Matthew simply could have omitted this detail because of the unanswered questions it raises. In addition to the Lukan-Matthean agreement of omission, two further factors have led us to suppose that the reference to the additional boats is the author of Mark’s own invention. First, the additional boats detract from the Jonah typology present in Quieting a Storm.[59] Second, we have determined that εἶναι μετά (einai meta, “to be with”) at various places elsewhere in Mark is redactional.[60] That the author of Mark redactionally inserted εἶναι μετά elsewhere in his Gospel increases the likelihood that εἶναι μετά is also redactional here. Since the reference to the other boats appears to be a Markan contribution to Quieting a Storm, we have omitted this detail from GR and HR.

L12 ἠκολούθησαν αὐτῷ (Matt. 8:23). In place of Mark’s reference to other boats “being with” Jesus, Matthew’s Gospel describes the disciples “following” Jesus. The presence of ἀκολουθεῖν (akolouthein, “to follow”) in Matt. 8:23 ties Quieting a Storm more closely to the version of Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple that the author of Matthew inserted between Jesus’ order to depart across the lake and the boarding of the boat (see above, Comment to L7).[61] In Matthew’s version of Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple ἀκολουθεῖν is prominent in the accounts of both prospective disciples. The first prospective disciple asks to follow Jesus (Matt. 8:19). Jesus invites the second prospective disciple to follow him (Matt. 8:22). Since the insertion of Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple into Quieting a Storm is redactional, the use of ἀκολουθεῖν in Matt. 8:23 to tie these pericopae together is likely to be redactional too. Thus, we have rejected Matthew’s wording in L12 for GR.

L13 αὐτὸς καὶ οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark to make reference to Jesus’ disciples is a fairly strong indication that the disciples were referred to in Anth.[62] Streeter overstated his case when he dismissed the significance of this “minor agreement” by claiming that “the disciples” were the inevitable choice for naming Jesus’ traveling companions.[63] The author of Luke refers to Jesus’ companions as “the Twelve” both before (Luke 8:1) and after (Luke 9:1) Quieting a Storm. The author of Matthew refers to Jesus’ companions as “the men” in Quieting a Storm itself (Matt. 8:27; see below, Comment to L51). So, options other than “the disciples” were available to both authors. Thus, the Lukan-Matthean minor agreement is probably more than mere coincidence.

As we noted above in Comment to L9, Luke’s pronoun αὐτός (avtos, “he”) fits better in L13 than in L9 from the point of view of Hebrew syntax. The sentence structure of our reconstruction is comparable to the opening verse of the book of Ruth:

| GR | Ruth 1:1 (LXX) |

| καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν ἐκείναις ταῖς ἡμέραις καὶ ἐνέβη εἰς πλοῖον αὐτὸς καὶ οἱ μαθηταὶ αὐτοῦ | καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῷ κρίνειν τοὺς κριτὰς…καὶ ἐπορεύθη ἀνὴρ ἀπὸ Βαιθλεεμ τῆς Ιουδα τοῦ παροικῆσαι ἐν ἀγρῷ Μωαβ, αὐτὸς καὶ ἡ γυνὴ αὐτοῦ καὶ οἱ υἱοὶ αὐτοῦ |

| And it happened in those days and he embarked upon a boat, he and his disciples. | And it happened in the judging of the judges…and a man went from Bethlehem of Judea to reside in the field of Moab, he and his wife and his sons. |

| HR | Ruth 1:1 (MT) |

| וַיְהִי בַּיָּמִים הָהֵם וַיֵּרֶד לִסְפִינָה הוּא וְתַלְמִידָיו | וַיְהִי בִּימֵי שְׁפֹט הַשֹּׁפְטִים…וַיֵּלֶךְ אִישׁ מִבֵּית לֶחֶם יְהוּדָה לָגוּר בִּשְׂדֵי מוֹאָב הוּא וְאִשְׁתּוֹ וּשְׁנֵי בָנָיו |

| And it was in those days and he embarked upon a boat, he and his disciples. | And it was in the days of the judging of the judges…and a man went from Bethlehem of Judah to live in the plains of Moab, he and his wife and his two sons. |

הוּא וְתַלְמִידָיו (HR). On reconstructing μαθητής (mathētēs, “pupil,” “disciple”) with תַּלְמִיד (talmid, “pupil,” “disciple”), see Lord’s Prayer, Comment to L4.

An anecdote reported in rabbinic sources bears striking similarities to Quieting a Storm:

מעשה ברבן גמליאל שהיה בא בספינה והיו תלמידיו עמו ועמד עליהן סער גדול בים אמ′ לו רבי התפלל עלינו אמר אלהינו רחם עלינו אמ′ לו רבי כדאי אתה שיחול שם שמים עליך אמר אלהי רחם עלינו

An anecdote concerning Rabban Gamliel, who was sailing in a boat and his disciples were with him. And a great storm arose against them in the sea. They said to him, “Rabbi! Pray for us!” He said, “Our God, have mercy on us.” They said to him, “Rabbi! You are worthy that the name of Heaven should be profaned on your behalf.” He said, “My God, have mercy on us.” (Midrash Tannaim 25:3 [ed. Hoffmann, 172])

Like Jesus in Quieting a Storm, Rabban Gamliel[64] traveled by boat with his disciples and was caught in a storm. And like Jesus’ disciples, Rabban Gamliel’s disciples turned to their master for help.

There are also striking differences between Quieting a Storm and the anecdote about Rabban Gamliel. Unlike Quieting a Storm, the rabbinic anecdote does not make much use (if any) of Jonah typology.[65] Also unlike Quieting a Storm, no miracle is reported. The anecdote implies that Rabban Gamliel’s second prayer was effective, but we are not told that the storm rapidly abated. It may simply be that the rabbi and his disciples weathered the storm and lived to tell the tale. The anecdote does, however, paint an exalted portrait of Rabban Gamliel, much as Quieting a Storm presents an exalted image of Jesus.[66] The rabbinic anecdote illustrates the principle that the divine name may be profaned for the sake of a spiritual virtuoso (מחילין שם שמים על היחיד). In the anecdote Rabban Gamliel initially declines to separate himself from his companions, praying, “Our God, have mercy on us.” But when this prayer proves ineffective, Rabban Gamliel highlights his unique status, praying, “My God, have mercy on us.”

L14-17 (GR). Whether to include Jesus’ instruction to cross the lake in GR is a difficult decision. On the one hand, the instruction is not strictly necessary for the story to make sense, and since the First Reconstructor tended to abbreviate as well as improve Anth.’s Greek style, it is hard to explain why the First Reconstructor would have added these lines if they had not occurred in his source. Thus, we might conclude that Jesus’ instruction to cross the lake appeared in Anth. On the other hand, some of the vocabulary in L14-17 is typical of FR pericopae (see below, Comment to L15), which might indicate that the First Reconstructor did compose these lines. While it could be the case that L14-17 are an FR expansion, we think it is more likely that the First Reconstructor paraphrased instructions he found in Anth. Nevertheless, because L14-17 is in doubt, we have placed these lines in brackets for GR and HR.

L14 [καὶ εἶπεν πρὸς αὐτούς (GR). Luke’s wording in L14 poses no difficulty whatsoever with regard to Hebrew retroversion. Moreover, we have accepted the phrase εἶπεν πρὸς αὐτούς (eipen pros avtous, “he said to them”) elsewhere in LOY (cf., e.g., Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations, L10; Call of Levi, L58; Friend in Need, L1; Yeshua, His Mother and Brothers, L32-33; “The Harvest Is Plentiful” and “A Flock Among Wolves,” L40-41). We therefore feel comfortable adopting Luke’s wording in L14 for GR.

L15 διαπεράσομεν (GR). The verb διέρχεσθαι (dierchesthai, “to go through”), which occurs in Luke 8:22, may be indicative of FR redaction. It is certainly the case that διέρχεσθαι occurs in a much higher concentration in Luke than in Mark or Matthew,[67] and several of the Lukan instances of διέρχεσθαι appear in what are likely to be FR pericopae (Luke 5:15; 9:6; 17:11; 19:1). It may be, however, that the First Reconstructor wrote διέρχεσθαι in place of a different verb in Anth. such as διαπερᾶν (diaperan, “to cross over”). Not only his predilection for διέρχεσθαι but also the proximity of the cognate πέραν (peran, “across”) in L16 could explain such a change. It is upon this hypothesis that we have adopted διαπερᾶν in place of Luke’s διέρχεσθαι for GR. Note that instead of the subjunctive mood of διέλθωμεν (dielthōmen, “we might go through”) we have adopted the future tense form διαπεράσομεν (diaperasomen, “we will cross over”) for GR. We suspect that the First Reconstructor was also responsible for the subjunctive mood in L15.

נַעֲבֹר (HR). In LXX the verb διαπερᾶν is rare, but on the two occasions on which διαπερᾶν has a Hebrew equivalent in MT that equivalent is עָבַר (‘āvar, “cross”). Compare our reconstruction to the following question in Deuteronomy:

מִי יַעֲבָר לָנוּ אֶל עֵבֶר הַיָּם

Who will cross over for us to the other side of the sea? (Deut. 30:13)

τίς διαπεράσει ἡμῖν εἰς τὸ πέραν τῆς θαλάσσης

Who will cross over for us to the other side of the sea? (Deut. 30:13)

L16 εἰς τὸ πέραν τῆς θαλάσσης (GR). We suspect that the noun λίμνη (limnē, “lake”) is a correction to Anth.’s wording introduced by the First Reconstructor or the author of Luke. Whereas Hebrew has a single noun for any large body of water, יָם (yām), Greek distinguishes between a freshwater lake, λίμνη, and a saltwater θάλασσα (thalassa, “sea”). Nevertheless, the LXX translators were not always careful to distinguish between freshwater lakes and saltwater seas,[68] and we might expect the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua to have been equally as lax. A Greek author such as the First Reconstructor or the author of Luke, on the other hand, would likely be more sensitive to the distinction.[69] Later Greek writers antagonistic to Christianity would take the Gospels to task for referring to the freshwater lake in Galilee as a “sea,” as, for instance, in the following quotations from an unknown Greek philosopher:

οἱ γοῦν τὴν ἀλήθειαν τῶν τόπων ἀφηγούμενοί φασι θάλασσαν μὲν ἐκεῖ μὴ εἶναι, λίμνην δὲ μικρὰν ἐκ ποταμοῦ συνεστῶσαν ὑπὸ τὸ ὄρος κατὰ τὴν Γαλιλλαίαν χώραν παρὰ πόλιν Τιβεριάδα….

But those who relate the truth about that locality say that there is not a sea [θάλασσαν] there, but a small lake [λίμνην] coming from a river under the hill in the country of Galilee, beside the city of Tiberias…. (Macarius Magnes, Apocriticus 3:6 [ed. Harnack, 42])[70]

πῶς δὲ καὶ πάντες οἱ χοῖροι ἐκεῖνοι συνεπνίγησαν, λίμνης οὐ θαλάσσης βαθείας ὑπαρχούσης

And how did all those pigs drown, as it is a lake [λίμνης], not a deep sea [θαλάσσης]? (Macarius Magnes, Apocriticus 3:6 [ed. Harnack, 40])

Either the First Reconstructor, who ever sought to improve Anth.’s Greek, or the author of Luke could have changed θάλασσα to λίμνη in Quieting a Storm to save Christians from embarrassment.

לְעֵבֶר הַיָּם (HR). In LXX when the adverb πέραν (peran, “across”) occurs as a substantive (definite article + πέραν [“the far side”]) it usually does so as the translation of עֵבֶר (‘ēver, “far side”).[71] We also find that the LXX translators more often rendered עֵבֶר with πέραν than with any other alternative.[72]

The vast majority of instances of θάλασσα (thalassa, “sea”) in LXX occur as the translation of יָם (yām, “large body of water,” usually, “sea”).[73] Likewise, the LXX translators nearly always rendered יָם as θάλασσα.[74]

L17 ⟨καὶ διεπέρασαν⟩] (GR). We have, most unusually, placed GR for L17 within a double set of brackets. We have done so because of our great uncertainty whether anything equivalent to Luke’s “and they set out” occurred in Anth. Our uncertainty arises from the fact that the verb ἀνάγεσθαι (anagesthai, “to put out to sea,” “to launch”) does not occur elsewhere in the Gospels, but does appear with a fairly high frequency in Acts (Acts 13:13; 16:11; 18:21; 20:3, 13; 21:1, 2; 27:2, 4, 12, 21; 28:10, 11).[75] There is a high probability, therefore, that the author of Luke added καὶ ἀνήχθησαν (kai anēchthēsan, “and they put out from shore”) or that he wrote καὶ ἀνήχθησαν in place of something else in his source (FR). That something else in FR may have been καὶ διῆλθον (kai diēlthon, “and they went through”), which may itself have been the First Reconstructor’s replacement for καὶ διεπέρασαν (kai dieperasan, “and they crossed over”) in Anth. (see above, Comment to L15). All of this is highly speculative, but since the possibility remains that Luke’s wording in L17 retains an echo, however faint, of Anth.’s wording, we have preferred to place GR and HR in brackets rather than exclude L17 entirely.

[⟨וַיַּעַבְרוּ⟩ (HR). On reconstructing διαπερᾶν (diaperan, “to cross over”) with עָבַר (‘āvar, “cross”), see above, Comment to L15.

L18 πλεόντων δὲ αὐτῶν (GR). Typically we regard genitive absolute constructions with great suspicion, since they are un-Hebraic and frequently in the Gospels the product of Greek redaction. There are additional grounds for hesitancy with regard to Luke’s πλεόντων δὲ αὐτῶν (pleontōn de avtōn, “as they were sailing”), namely the verb πλεῖν (plein, “to sail”) does not occur elsewhere in the Synoptic Gospels,[76] but does occur 4xx in Acts (Acts 21:3; 27:2, 6, 24).[77] Moreover, we suspect that the reference to Jesus’ sleep in Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm (L19) has been moved up from its original position (see below, Comment to L19). Nevertheless, genitives absolute did sometimes occur in sources translated to Greek from Hebrew, and therefore probably also occurred in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

The genitive absolute construction in L18 deserves careful consideration because it is so similar to the wording of storm narratives in rabbinic sources. Versions of the stories of Nicanor’s doors and the precocious Jewish youth at sea, cited above in Comment to L9, and a story about Rabban Gamliel all contain statements equivalent to “as he/they was/were sailing” when describing the onset of a storm:

היו באין בספינה ועמד עליהן סער גדול בים

As they [i.e., Nicanor and his traveling companions—DNB and JNT] were sailing [הָיוּ בָּאִין] in a boat a great storm arose against them in the sea…. (y. Yom. 3:6 [19a-b])

היו באין בספינה ועמד עליהן נחשול בים

As they [i.e., the Jewish youth and his traveling companions—DNB and JNT] were sailing [הָיוּ בָּאִין] in a boat a gale arose against them in the sea…. (t. Nid. 5:17; Vienna MS)

ר″ג היה בא בספינה עמד עליו נחשול לטבעו

As Rabban Gamliel was sailing [הָיָה בָּא] in a boat a gale arose against him to sink him…. (b. Bab. Metz. 59b)

From these rabbinic accounts it appears that “as he was sailing” or “as they were sailing” was a stock phrase in descriptions of the onset of a storm. That “as they were sailing” should also appear in Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm in close proximity to the onset of the storm suggests that perhaps the earliest version of Quieting a Storm made similar use of stereotypical descriptions of the onset of storms. Thus, we have cautiously accepted Luke’s wording in L18 for GR.

וְהָיוּ בָּאִים (HR). Neither Biblical nor Mishnaic Hebrew had a specialized verb meaning “to sail.” Instead, Hebrew made do with the verb בָּא (bā’, “come,” “go,” “arrive”), as we saw in the examples cited above. The same usage is found in Jonah 1:3, where the LXX translators correctly rendered בָּא with πλεῖν (plein, “to sail”):

וַיֵּרֶד יָפוֹ וַיִּמְצָא אָנִיָּה בָּאָה תַרְשִׁישׁ וַיִּתֵּן שְׂכָרָהּ וַיֵּרֶד בָּהּ לָבוֹא עִמָּהֶם תַּרְשִׁישָׁה מִלִּפְנֵי יי

And he went down to Jaffa and found a ship sailing [lit., “going”] for Tarshish. And he paid the fare and boarded it [lit., “went down in it”] to sail [לָבוֹא, lit., “to go”] with them to Tarshish away from the LORD. (Jonah 1:3)

καὶ κατέβη εἰς Ιοππην καὶ εὗρεν πλοῖον βαδίζον εἰς Θαρσις καὶ ἔδωκεν τὸ ναῦλον αὐτοῦ καὶ ἐνέβη εἰς αὐτὸ τοῦ πλεῦσαι μετ̓ αὐτῶν εἰς Θαρσις ἐκ προσώπου κυρίου

And he went down to Joppa and found a boat bound for Tarsis, and he paid the fare and he boarded it to sail [τοῦ πλεῦσαι] with them to Tarsis from the face of the Lord. (Jonah 1:3)

The use of בָּא in the sense of “sail” also occurs in halachic discussions, for instance:

ספינה שהיתה באה בים ועמד עליה נחשול והקילו ממשאה

A boat that was sailing [בָּאָה (bā’āh, lit., “going”)] in the sea and a storm arose against it and they lightened its cargo…. (t. Bab. Metz. 7:14; Vienna MS)

The combination of הָיָה + participle in the sense of “as [he, she, it] was doing something” is characteristic of Mishnaic rather than Biblical Hebrew. If וְהָיוּ בָּאִים (vehāyū bā’im, “as they were sailing”) occurred in Quieting a Storm along with vav-consecutives (L1, L9, L14, L17, L30, L31, L32, L40, L41, L44, L46, L47, L50, L53) and vocabulary and forms that were discontinued in Mishnaic Hebrew (e.g., הִנֵּה in L20; לֵאמֹר in L33, L53), then we must assume that Quieting a Storm was composed in a mixed style of Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew such as we encounter in the baraita in b. Kid. 66a.

L19 ἀφύπνωσεν (Luke 8:23). The notice about Jesus’ sleep in Luke’s version of Quieting a Storm seems out of place whether we view it from the perspective of the story of Jonah, where we read a description of a storm (Jonah 1:4) before we hear about Jonah’s sleeping below deck (Jonah 1:5), or whether we view it from the perspective of stock descriptions in rabbinic sources of the onset of storms, where “while he/they was/were sailing” is followed by “and a storm arose” (see above, Comment to L18). We suspect that the First Reconstructor moved the notice about Jesus’ sleep from its original position in L30 to its present position in L19, which he deemed to be more logical.[78] Our attribution of this change to the First Reconstructor rather than to the author of Luke is supported by the fact that the verb ἀφυπνοῦν (afūpnoun, “to fall asleep”) occurs only this once in the Synoptic Gospels but nowhere else in NT. That the author of Luke did not use ἀφυπνοῦν in Acts, despite describing sleep in Acts 12:6 and Acts 20:9-10, may point to the First Reconstructor as the originator of ἀφυπνοῦν in Quieting a Storm.

L20 καὶ ἰδοὺ (GR). We believe Matthew’s highly Hebraic “And behold! A great storm on the sea!” reflects the wording of Anth. The First Reconstructor and the author of Luke both tended to avoid ἰδού (idou, “Behold!”), so Luke’s καὶ κατέβη (kai katebē, “and it descended”) may be regarded as a stylistic improvement to Anth.’s wording introduced by the First Reconstructor or, perhaps, the author of Luke. Mark’s καὶ γίνεται (kai ginetai, “and becomes”) may also be a paraphrase of Anth.’s καὶ ἰδού. In any case, Mark’s use of the historical present tense looks like Markan redaction.[79]

We note that in LXX we sometimes find genitive absolute constructions followed by καὶ ἰδού, such as we have in our Greek Reconstruction (L18-20), as in the following examples:

αὐτῶν δὲ ἀγαθυνθέντων τῇ καρδίᾳ αὐτῶν καὶ ἰδοὺ οἱ ἄνδρες τῆς πόλεως υἱοὶ παρανόμων περιεκύκλωσαν τὴν οἰκίαν

While they were good [αὐτῶν δὲ ἀγαθυνθέντων; MT: הֵמָּה מֵיטִיבִים] in their hearts, and behold [καὶ ἰδοὺ]! The men of the city, sons of lawlessness, surrounded the house…. (Judg. 19:22)

αὐτῶν εἰσπορευομένων εἰς μέσον τῆς πόλεως καὶ ἰδοὺ Σαμουηλ ἐξῆλθεν εἰς ἀπάντησιν αὐτῶν

While they were entering [αὐτῶν εἰσπορευομένων; MT: הֵמָּה בָּאִים] into the middle of the city, and behold [καὶ ἰδοὺ]! Samuel came out to their meeting. (1 Kgdms. 9:14)

καὶ ἐγένετο αὐτῶν πορευομένων ἐπορεύοντο καὶ ἐλάλουν, καὶ ἰδοὺ ἅρμα πυρὸς καὶ ἵπποι πυρὸς καὶ διέστειλαν ἀνὰ μέσον ἀμφοτέρων

And it happened while they were walking [αὐτῶν πορευομένων; MT: הֵמָּה הֹלְכִים], they were walking and talking, and behold [καὶ ἰδοὺ]! A chariot of fire and horses of fire! And they separated between both…. (4 Kgdms. 2:11)

καὶ ἐγένετο αὐτῶν θαπτόντων τὸν ἄνδρα καὶ ἰδοὺ εἶδον τὸν μονόζωνον….

And it happened while they were burying [αὐτῶν θαπτόντων; MT: הֵם קֹבְרִים] the man, and behold [καὶ ἰδοὺ]! They saw the lightly armed man…. (4 Kgdms. 13:21)

Similar to our reconstruction, in each of the examples cited above a participial phrase followed by a וְהִנֵּה (vehinēh, “And behold!”) clause was rendered in LXX with a genitive absolute construction followed by a καὶ ἰδού clause. These examples bolster our confidence in our decisions for GR and HR in L18-20 of Quieting a Storm.

L21 σεισμὸς μέγας (GR). Whereas the Lukan and Markan versions of Quieting a Storm refer to the storm as a λαῖλαψ ἀνέμου (lailaps anemou, “windstorm”),[80] Matthew’s version refers to it as a σεισμός (seismos, “shaking”). The noun σεισμός can be used for earthquakes, but it can also denote tremors and upheavals of various kinds.[81] Some scholars attribute the presence of σεισμός in Matt. 8:24 to the author of Matthew’s special interest in earthquakes,[82] but despite the use of the noun σεισμός, it is clearly a storm on the sea, not a quaking of the earth, that the author of Matthew describes in Quieting a Storm. Other scholars have made the convoluted suggestion that the σεισμός in Matt. 8:24 would have reminded readers of the tumultuous times leading up to the eschaton, which would include, inter alia, earthquakes and persecution, and since Matthew’s readers had experienced (or currently were experiencing) persecution, the use of σεισμός in Quieting a Storm would enable Matthew’s readers to more easily identify with the plight of the disciples.[83] A simpler and, in our view, more probable explanation is that the author of Matthew wrote σεισμός because this was the term he found in Anth. Supposing σεισμός (“disturbance”) was Anth.’s reading, λαῖλαψ ἀνέμου (“windstorm”) could be regarded as a Greek improvement introduced by the First Reconstructor, which was then passed on to Luke. Mark’s λαῖλαψ μεγάλη ἀνέμου (lailaps megalē anemou, “big windstorm”) would then be a compromise between σεισμὸς μέγας (“big disturbance”) in Anth. and λαῖλαψ ἀνέμου (“windstorm”) in Luke.

Note that none of the synoptic evangelists used the description κλύδων μέγας (klūdōn megas, “big raging water”) found in Jonah 1:4. It seems that despite the clear Jonah imagery in Quieting a Storm, neither the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua nor any of the authors of the Synoptic Gospels attempted to imitate the Septuagint’s vocabulary.[84]

סַעַר גָּדוֹל (HR). Two terms for “storm” appear in rabbinic storm narratives: נַחְשׁוֹל (naḥshōl, “gale”) and סַעַר גָּדוֹל (sa‘ar gādōl, “great storm”). Since נַחְשׁוֹל and סַעַר גָּדוֹל occur in parallel accounts of the same stories,[85] it is clear that the two terms are interchangeable. Perhaps נַחְשׁוֹל was the colloquial term while סַעַר גָּדוֹל was intended to invoke the story of Jonah (cf. Jonah 1:4). Since we think σεισμὸς μέγας occurred in Anth., it is probable that this was a non-Septuagintal rendering of סַעַר גָּדוֹל.

In LXX σεισμός is usually the translation of רַעַשׁ (ra‘ash, “shaking,” “earthquake”)[86] and never occurs as the translation of סַעַר (sa‘ar, “storm”).[87] But in Jer. 23:19 the phrase ἰδοὺ σεισμὸς παρὰ κυρίου (idou seismos para kūriou, “Behold! A shaking from the Lord”) occurs as the translation of הִנֵּה סַעֲרַת יי (hinēh sa‘arat YY, “Behold! A storm of the LORD”). The rendering of סְעָרָה (se‘ārāh, “storm”), a close cognate of סַעַר, as σεισμός in Jer. 23:19 strengthens the credibility of our reconstruction in L21.

On reconstructing the adjective μέγας (megas, “big”) with גָּדוֹל (gādōl, “big”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L22.

Gustaf Dalman (1855-1941) described two occasions in the early twentieth century on which he personally experienced windstorms on the Sea of Galilee:

The months from March to July are generally the windiest, with the west wind predominating. Autumn and winter are quieter, which does not, however, exclude some stormy days. The members of the Archaeological Institute experienced such a bad day on April 9, 1907. We ourselves rode in the morning to the Seven Springs, but saw boats on the lake struggling against wind and waves. One of them, which was to have brought one of our company over the lake, landed in the land of Ginnesar, far from its destination, because the majority of the sailors considered a further journey impossible. (Dalman, Sacred Sites and Ways, 182-183)[88]

Coming [on April 6, 1908—DNB and JNT] from the eastern edge below Hippos [or Susita, near the modern-day kibbutz of Ein Gev—DNB and JNT], we wished to sail northward along the shore in order to land again in Bethsaida. But a strong wind rising at noon from the east made it impossible to land, and drove us to Capernaum. (Dalman, Sacred Sites and Ways, 176)[89]

L22 ἔστη ἐπ̓ αὐτοὺς ἐν τῇ θαλάσσῃ (GR). The surest part of our reconstruction in L22 is the prepositional phrase ἐν τῇ θαλάσσῃ (en tē thalassē, “in the sea”), which is supported by the Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark’s omission to write preposition + definite article + noun for body of water. As we discussed above in Comment to L16, Luke’s use of λίμνη (limnē, “lake”) is probably a substitution introduced by the First Reconstructor for Anth.’s improper use of θάλασσα (thalassa, “sea”) in reference to the lake in Galilee. Thus, Matthew’s ἐν τῇ θαλάσσῃ (en tē thalassē, “in the sea”) is more likely to reflect Anth.’s wording than Luke’s εἰς τὴν λίμνην (eis tēn limnēn, “into the lake”).

Whereas Matthew has an aorist form of the verb γίνεσθαι (ginesthai, “to be”), we have adopted an aorist form of ἑστάναι (hestanai, “to stand”) for GR. Matthew’s ἐγένετο (egeneto, “it was”) may be a reflection of Mark’s γείνεται (geinetai, “it becomes”) in L20, while ἔστη (estē, “it stood”) reflects our supposition that the earliest form of Quieting a Storm drew on the stock descriptions of boats caught in storms found in rabbinic sources. In those rabbinic accounts we encounter variations on “a storm arose against him/them” in which the verb for “arose” is עָמַד (‘āmad, “stand”): וְעָמַד עֲלֵיהֶן סַעַר גָּדוֹל בַּיָּם (ve‘āmad ‘alēhen sa‘ar gādōl bayām, “and a great storm arose against them [i.e., Rabban Gamliel and his disciples] in the sea”; Midrash Tannaim 25:3); עָמַד עָלָיו נַחְשׁוֹל לְטֹבְעוֹ (‘āmad ‘ālāv naḥshōl leṭov‘ō, “a storm arose against him [i.e., Rabban Gamliel] to sink him”; b. Bab. Metz. 59b); עָמַד עֲלֵיהֶן נַחְשׁוֹל שֶׁבַּיָּם לְטֹבְעָן (‘āmad ‘alēhen naḥshōl shebayām leṭov‘ān, “a storm of the sea arose against them [i.e., Nicanor and his companions] to sink them”; t. Yom. 2:4); וְעָמַד עֲלֵיהֶן סַעַר גָּדוֹל בַּיָּם (ve‘āmad ‘alēhen sa‘ar gādōl bayām, “and a great storm arose against them [i.e., Nicanor and his companions] in the sea”; y. Yom. 3:6 [19a-b]); עָמַד עָלָיו נַחְשׁוֹל שֶׁבַּיָּם לְטֹבְעוֹ (‘āmad ‘ālāv naḥshōl shebayām leṭov‘ō, “a storm of the sea arose against him [i.e., Nicanor] to sink him”; b. Yom. 38a); וְעָמַד עֲלֵיהֶן נַחְשׁוֹל בַּיָּם (ve‘āmad ‘alēhen naḥshōl bayām, “and a storm arose against them [i.e., the Jewish youth and his companions] in the sea”; t. Nid. 5:17); עָמַד עֲלֵיהֶם סַעַר גָּדוֹל בַּיָּם (‘āmad ‘alēhem sa‘ar gādōl bayām, “a great storm arose against them [i.e., the Jewish youth and his companions] in the sea”; y. Ber. 9:1 [63b]). In the continuation of a variant version of the story of Titus cited above in Comment to L9 we likewise read, עָמַד עָלָיו נַחְשׁוֹל שֶׁבַּיָּם לְטוֹבְעוֹ (‘āmad ‘ālāv naḥshōl shebayām leṭōv‘ō, “a storm of the sea arose against him [i.e., Titus] to sink him”; b. Git. 56b). Even if the author of Matthew saw καὶ ἰδοὺ σεισμὸς μέγας ἔστη ἐπ̓ αὐτοὺς ἐν τῇ θαλάσσῃ (“And behold! A great shaking stood upon them in the sea”) in Anth., as we suppose, he may not have understood the underlying Hebrew idiom and, like the First Reconstructor, preferred to adopt a substitute.

עָמַד עֲלֵיהֶם בַּיָּם (HR). On reconstructing ἑστάναι (hestanai, “to stand”) with עָמַד (‘āmad, “stand”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L14. The rabbinic sources cited in the preceding paragraph demonstrate why we think עָמַד is a good choice for HR.

On reconstructing ἐπί (epi, “on,” “upon”) with עַל (‘al, “on,” “upon,” sometimes “against”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L11.

On reconstructing θάλασσα (thalassa, “sea”) with יָם (yām, “sea”), see above, Comment to L16.

As in L18, so in L22 we have adopted Mishnaic-style Hebrew for HR despite our general preference for biblicizing Hebrew when reconstructing narrative. The result is a mixed style of Hebrew such as we encounter in the baraita preserved in b. Kid. 66a.

L23-26 It is our belief that neither Luke nor Mark nor Matthew preserves Anth.’s wording in describing the effects of the storm upon the boat and its passengers. Luke has “and they were being filled and they were in danger.” Luke’s Greek is difficult to reconstruct in Hebrew,[90] and the vocabulary is unique to Luke in the Synoptic Gospels.[91] Probably Luke’s wording reflects the First Reconstructor’s paraphrase of the description he read in Anth.[92]

In place of Luke’s colorless statement of the bare facts that they were filling up and in danger, Mark has a description of how the filling up was taking place (“the waves were tossing into the boat”; L23-24) followed by a ὥστε (hōste, “so that”) clause (viz., “so that the boat was already full”).[93] The author of Mark may have picked up “waves” from Luke 8:24, where Jesus rebukes “the waves of water” (L42). The ὥστε clause has no syntactical parallel in Luke, but the information it conveys, “so that the boat was already full,” is essentially the same as Luke’s “they were being filled” (L24). We wonder, however, whether Mark’s ὥστε clause reflects something the author of Mark found in Anth.

Matthew’s “so that the boat was being covered by the waves” is a simplification of Mark’s wording, and the passive + ὑπό construction does not revert readily to Hebrew. Some scholars suppose that “so that the boat was being covered by the waves” means that the waves hid the boat from view,[94] but the author of Matthew does not tell his readers that there were witnesses in other boats or on the shore from whom the boat might be hidden. Perhaps, therefore, it is best to take Matthew’s meaning to be that the waves were covering the boat by washing over it.

L25 ὥστε βυθίζειν αὐτούς (GR). Recovering the wording of Anth. when what we find in each of the Synoptic Gospels appears to be redactional is extremely challenging, but in the present case we have the rabbinic storm narratives to guide us. In the rabbinic storm narratives we have collected, we frequently find “a storm arose” followed by a purpose clause, either לְטֹבְעוֹ (leṭov‘ō, “to sink him”) or לְטֹבְעָן (leṭov‘ān, “to sink them”). In Greek this purpose clause might be represented as ὥστε βυθίζειν αὐτόν (hōste būthizein avton, “in order to sink him”) or ὥστε βυθίζειν αὐτούς (hōste būthizein avtous, “in order to sink them”; cf. Luke 5:7). Just as we suppose the First Reconstructor changed “And behold! A great storm arose against them in the sea” to “And a windstorm descended onto the lake,” so we suppose he changed “in order to sink them” to “and they were being filled and were in danger.” The author of Mark, who knew both Luke and Anth., paraphrased a combination of their descriptions resulting in his description of the waves followed by a ὥστε clause. The author of Matthew wished to streamline Mark’s wording, and since he found a ὥστε clause in both his sources, he composed a ὥστε clause of his own.

לְטֹבְעָן (HR). The verb טָבַע (ṭāva‘, “sink”) occurs in Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew. As we have seen, it was common to include טָבַע in the infinitive with a pronominal suffix in rabbinic storm narratives.[95] The idiom has a mild personifying effect, attributing intentionality to the storm (“the storm arose against him/them to sink him/them”), but we should be cautious of reading too much into the idiom. None of the rabbinic storm narratives we have surveyed portray the storms as having personal agency. The idiom may have its origin in a mythical understanding of storms, but if so, the mythical understanding was no longer activated simply by the use of the idiom.

L27 καὶ αὐτὸς (GR). As we noted above in Comment to L19, we believe the First Reconstructor repositioned the reference to Jesus’ repose to what he deemed to be a more logical location, describing how Jesus fell asleep before the onset of the storm. The Markan and Matthean placement of the notice about Jesus’ sleep is reminiscent of the story of Jonah, where the storm is described before it is stated that Jonah was asleep below deck. Indeed, “and he…was sleeping” in Mark and Matthew even looks like the disjunctive clause in Jonah 1:5:

וְיוֹנָה יָרַד אֶל יַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה וַיִּשְׁכַּב וַיֵּרָדַם

But Jonah had gone down to the farthest part of the ship and had lain down and had gone sound to sleep. (Jonah 1:5)

Ιωνας δὲ κατέβη εἰς τὴν κοίλην τοῦ πλοίου καὶ ἐκάθευδεν καὶ ἔρρεγχεν

But Jonah went down into the belly of the ship and was sleeping and snoring. (Jonah 1:5)

Since Mark’s καὶ αὐτός (kai avtos, “and he”) is even more Hebraic than Matthew’s αὐτὸς δέ (avtos de, “but he”), we have accepted Mark’s wording for GR.[96]

L28 ἐκοιμήθη ἐν τῇ πρύμνῃ (GR). Mark’s description of Jesus asleep in the stern is so like the description of Jonah’s sleep below deck that it cannot easily be dismissed as redactional. Although the imagery is nearly the same, Mark’s wording is not that of LXX, so it is unlikely that the author of Mark was attempting to conform his version of Quieting a Storm to the story of Jonah. Mark’s wording could, however, reflect a source that alluded in Greek to the story of Jonah while bypassing LXX. Anth. was just such a source. The scriptural allusions in Anth. are usually independent of LXX; they reflect the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua’s direct translation of his Hebrew source. Thus, whereas the LXX translators rendered יַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה (yarketē hasefināh, “the farthest part of the boat”) in Jonah 1:5 as ἡ κοίλη τοῦ πλοίου (hē koilē tou ploiou, “the belly of the boat”), an independent translator might have rendered the same phrase more succinctly as ἡ πρύμνα (hē prūmna, “the stern”).[97]

Aside from the allusion to the Jonah story, there are two additional reasons why a description of Jesus’ location in the boat is likely to have been present in Anth. First, Jesus’ location in the stern explains how Jesus could have remained asleep despite the storm.[98] Boats such as the one discovered near Magdala had decks at the stern where fishing nets were stored.[99] The space under the deck would have provided a space for Jesus to sleep that would have sheltered him from the wind, the splashing of waves, and the falling of rain that would otherwise certainly have awakened him.[100] Second, Jesus’ location at the stern below the deck would explain an otherwise mysterious detail in the Lukan and Matthean versions of Quieting a Storm. According to Luke and Matthew, the disciples approached Jesus in order to awaken him, which suggests that Jesus was in a space separate from the other passengers. Beneath the deck at the stern is the most probable location for the disciples to have approached Jesus. The omission of Jesus’ location in Luke and Matthew probably reflects the epitomizing tendencies of the First Reconstructor and the author of Matthew.

There is one point in L28 at which the author of Mark may have changed the wording of his source. Mark has the verb ἦν (ēn, “he was being”), of which, despite its blandness, the author of Mark was fond (cf. his insertion of ἦν in L10). What verb might Anth. have used instead? It cannot escape our notice that Jonah 1:5 attributes three actions to the prophet: Jonah “went down” (יָרַד) below deck, he “lay down” (וַיִּשְׁכַּב), and he “slept soundly” (וַיֵּרָדַם). For boats as small as those that plied the Sea of Galilee יָרַד (yārad, “go down”) might not be the right verb for lying down beneath the stern deck, but שָׁכַב (shāchav, “lie down”) would do nicely. We could therefore imagine that the Hebrew Life of Yeshua said וְהוּא שָׁכַב בְּיַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה וַיֵּרָדֵם (vehū’ shāchav beyarketē hasefināh vayērādēm, “but he lay down in the back of the boat and slept soundly”), imitating the wording of Jonah as closely as possible while remaining true to the physical realities of a small fishing vessel. Such a statement might have been translated as καὶ αὐτὸς ἐκοιμήθη ἐν τῇ πρύμνῃ καὶ ἐκάθευδεν (kai avtos ekoimēthē en tē prūmnē kai ekathevden), by which the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua meant, “and he lay in the stern and slept,” but which the author of Mark might have understood as “and he slept in the stern and slept,” since the verb κοιμᾶν (koiman) can mean both “to lie down” and “to sleep.” Regarding the first sleeping verb as redundant, the author of Mark could easily have replaced ἐκοιμήθη (ekoimēthē, “he fell asleep”) with ἦν (ēn, “he was being”).

שָׁכַב בְּיַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה (HR). In LXX most instances of κοιμᾶν (koiman, “to lie down,” “to sleep”) occur as the translation of שָׁכַב (shāchav, “lie down”).[101] We also find that the LXX translators rendered שָׁכַב more often as κοιμᾶν than as any other verb.[102]

The noun πρύμνα (prūmna, “stern”) does not occur in LXX. As we noted above, the LXX translators rendered the phrase יַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה in Jonah 1:5 as ἡ κοίλη τοῦ πλοίου (hē koilē tou ploiou, “the belly of the boat”), but πρύμνα might be regarded as a less literalistic translation of יַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה. The use of the noun יַרְכָתַיִם (yarchātayim, “furthest parts”) in a construct phrase with the sense of “back of the __” is well attested in the Hebrew Scriptures, for instance:

וּלְיַרְכְּתֵי הַמִּשְׁכָּן יָמָּה תַּעֲשֶׂה שִׁשָּׁה קְרָשִׁים

And for the back of the tabernacle [יַרְכְּתֵי הַמִּשְׁכָּן] to the west you must make six frames. (Exod. 26:22)

וְדָוִד וַאֲנָשָׁיו בְּיַרְכְּתֵי הַמְּעָרָה יֹשְׁבִים

…but David and his men were sitting in the back of the cave [יַרְכְּתֵי הַמְּעָרָה]. (1 Sam. 24:4)

Whereas in Jonah 1:5 יַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה means “deep inside the ship,” i.e., “below deck,” in Quieting a Storm יַרְכְּתֵי הַסְּפִינָה would mean “at the back of the boat.”

L29 ἐπὶ τὸ προσκεφάλαιον (Mark 4:38). The portrayal of Jesus asleep at the stern has a strong parallel in the story of Jonah, where the prophet sleeps below deck despite the raging of the storm. The detail about Jesus’ pillow, on the other hand, has no parallel in the story of Jonah. This peculiar detail is also conspicuously absent in the parallel versions of Quieting a Storm in Matthew and Luke. While some scholars have regarded the mention of Jesus’ pillow as proof that Mark’s story is derived from an eyewitness account,[103] it is equally plausible that the author of Mark added the pillow reference in order to make the scene more vivid.[104]