How to cite this article:

David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “Innocent Blood,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2021) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/22415/].

(Matt. 23:34-36; Luke 11:49-51)[1]

Updated: 1 March 2026

לְפִיכָךְ אַף חָכְמַת אֱלֹהִים אָמְרָה אֶשְׁלַח בָּהֶם נְבִיאִים וּשְׁלִיחִים וַחֲכָמִים וְסוֹפְרִים מֵהֶם יַהֲרֹגוּ מֵהֶם יִרְדֹּפוּ וְיִדָּרֵשׁ כָּל דָּם נָקִי שָׁפוּךְ עַל הָאָרֶץ מִיַּד הַדּוֹר הַזֶּה מִדַּם הֶבֶל וְעַד דַּם זְכַרְיָה הָאוֹבֵד בֵּין הַמִּזְבֵּחַ וּבֵין הַבַּיִת אָמֵן אֲנִי אוֹמֵר לָכֶם יִדָּרֵשׁ מִיַּד הַדּוֹר הַזֶּה

“Thus Lady Wisdom herself declared, ‘I will send them prophets and emissaries, sages and scribes. They will kill the former and harry the latter. Therefore, this generation will have to answer for all the innocent blood poured out on the holy land, from the murder of Hevel down to that of Zecharyah, who died between the altar and the Temple.’

“Alas, what Lady Wisdom said is also true of you! God will demand from this generation all the innocent blood ever poured out because you will not repent.”[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Innocent Blood click on the link below:

Story Placement

In the Gospels of Matthew and Luke Innocent Blood occurs in similar, though not identical, contexts. In Matthew Innocent Blood is placed between Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees, which in Matthew consists of a series of seven woes pronounced against the scribes and Pharisees (Matt. 23:13-32), and Jesus’ Lament for Yerushalayim (Matt. 23:37-39). In Luke Innocent Blood is sandwiched between several woes pronounced against Pharisees and Torah experts (Luke 11:42-48) and a final woe pronounced against Torah experts (Luke 11:52). Meanwhile, Luke’s version of Jesus’ Lament for Yerushalayim occurs in an altogether different context (Luke 13:34-35). The Lukan-Matthean agreement to associate Innocent Blood with Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees likely reflects the arrangement of these two pericopae in the Anthology (Anth.).

It was probably the Anthologizer who brought the series of woes and Innocent Blood together. The different styles in which they are composed (woe pronouncements versus quotation of a pseudepigraphical source) and the different audiences to which they are addressed (Pharisees or other leaders addressed in the second person versus “this generation” spoken of in the third person) suggest that these two pericopae did not originally form a literary unit.[3] An associative method of placing similarly themed pericopae at the end of larger blocks of material appears to have been typical of the Anthologizer’s editorial style. Elsewhere we have observed that the Anthologizer placed Like Children Complaining, which mentions John the Baptist, at the end of a larger block of material concerning Jesus and John the Baptist.[4] Likewise, the Anthologizer appears to have tacked Woes on Three Villages at the end of the Sending the Twelve discourse because Woes on Three Villages mentions the destruction of Sodom, as does a saying that occurs toward the end of the Sending the Twelve discourse.[5]

The author of Luke is probably responsible for tucking Innocent Blood inside the series of woes.[6] Tucking tacked-on pericopae inside discourses seems to have been one of the author of Luke’s methods for more fully integrating units of loosely connected pericopae. The author of Luke had employed this method when he tucked Woes on Three Villages inside the Sending discourse by combining Jesus’ saying about the fate of inhospitable towns with Woes on Three Villages.[5]

The author of Matthew is probably responsible for associating Innocent Blood with Lament for Yerushalayim. This conclusion is supported by the likelihood that the author of Matthew supplemented Anth.’s block of material centered on the series of woes and Innocent Blood with additional sayings (e.g., Matt. 23:2-3, 8-10, 11-12, 16-22, 33). It is also supported by the likelihood that the author of Luke copied his version of Lament for Yerushalayim from a source different than that from which he had copied the series of woes in Luke 11 parallel to those in Matt. 23. For whereas the Lukan and Matthean versions of the series of woes exhibit quite low levels of verbal agreement, the Lukan and Matthean versions of Lament for Yerushalayim are characterized by strong verbal identity.[7] The Lukan and Matthean versions of Innocent Blood, too, are characterized by relatively low levels of verbal agreement. Thus, the author of Luke probably took the series of woes and Innocent Blood from a source that did not associate them with Jesus’ Lament for Yerushalayim, otherwise the author of Luke probably would have agreed with Matthew’s placement of Lament for Yerushalayim, though in a version that was worded rather differently than Matthew’s.

All this leaves us to consider where Innocent Blood might have appeared in relation to other pericopae in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua. Flusser noted that Innocent Blood shares certain themes and vocabulary in common with Generations That Repented Long Ago.[8] These include warnings of societal disaster, condemnation of violence,[9] the term σοφία (sofia, “wisdom”; Generations That Repented Long Ago, L13; Innocent Blood, L2) and the phrase ἡ γενεὰ αὕτη (hē genea havtē, “this generation”; Generations That Repented Long Ago, L10, L17; Innocent Blood, L17, L26). Both pericopae are also united by the notion of persons from the scriptural past—whether the Queen of Sheba or the people of Nineveh in Generations That Repented Long Ago, or the two murder victims, Abel and Zechariah, in Innocent Blood—condemning Jesus’ contemporaries. Innocent Blood’s reference to sending prophets and wise men also fits neatly with the figures of Solomon (a wise man) and Jonah (a prophet) who feature in Generations That Repented Long Ago. These shared features suggest that Innocent Blood may have belonged to the same narrative-sayings complex as Generations That Repented Long Ago, a complex we have entitled “Choose Repentance or Destruction.”

For an overview of the complete “Choose Repentance or Destruction” complex, click here.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

Innocent Blood has a complicated and unusual transmission history. According to Luke’s version of Innocent Blood, Jesus quoted an otherwise unknown Second Temple-period Jewish source in which the Wisdom of God[10] speaks to “this generation” about the murders of Abel (Gen. 4) and Zechariah (2 Chr. 24).[11] In having Jesus quote from a pre-existing Jewish source, Luke’s version is surely correct, since a parallel to the source Jesus quoted is embedded in the book of Jubilees.[12] As scholars have noted, the Jubilees passage itself is deeply indebted to 2 Chr. 24:17ff., which recounts the murder of Zechariah the priest.[13] It will therefore be useful to present the scriptural verses, the Jubilees passage and the quotation spoken by the Wisdom of God in parallel columns:

| 2 Chr. 24:17-23 | Jubilees 1:10-13[14] | Jesus’ Pseudepigraphon (reconstructed) |

| And after the death of Jehoiada the princes of Judah came and prostrated themselves to the king [i.e., Joash—DNB and JNT]. Then the king listened to them. And they abandoned the house of the LORD, the God of their fathers, and they served the Asherahs and the idols, and there was wrath against Judah and Jerusalem because of this, their guilt. | And many will perish and they will be taken captive and will fall into the hands of the enemy, because they have forsaken My ordinances and My commandments, and the festivals of My covenant, and My sabbaths…and My sanctuary which I have allowed for Myself in the midst of the land, that I should set My name upon it, and that it should dwell (there). And they will make to themselves high places and groves and graven images, and they will worship, each his own (graven image), so as to go astray… | |

| So he sent them prophets to return them to the LORD, and they testified against them, but they did not listen. And the Spirit of God endued Zechariah son of Jehoiada the priest, and he stood above the people and he said to them, “Thus has God spoken: Why are you transgressing the LORD’s commandments? But you will not have success because you have forsaken the LORD and he has forsaken you.” | And I will send witnesses unto them, that I may witness against them, but they will not hear, | I will send to them prophets and apostles, and sages and scribes, |

| And they conspired against him and stoned him with stones by the king’s command in the courtyard of the house of the LORD. And Joash the king did not remember the faithfulness that Jehoiada his father had done for him, but he killed his son. | and will slay the witnesses also, and they will persecute those who seek the law, and they will abrogate and change everything so as to work evil before my eyes. | and some of them they will kill, and some of them they will persecute, |

| And as he died he said, “Let the LORD see and require it!” And at the turn of the year the army of Aram arose against him and came to Judah and Jerusalem and destroyed all the princes of the people from among the people, and all their spoil they sent to the king of Damascus. | And I shall hide My face from them and I shall deliver them into the hand of the Gentiles for captivity, and for a prey, and for devouring, and I shall remove them from the midst of the land, and I shall scatter them amongst the Gentiles. | so that all the innocent blood poured on the earth will be required of this generation, from the blood of Abel unto the blood of Zechariah, who perished between the altar and the sanctuary. |

The scriptural account describes how Joash, one of the kings of Judah, being misled by the princes of the people, turned away from the LORD to worship idols. When rebuked by the prophets, he refused to listen. Even worse, the king conspired with the princes to murder Zechariah the priest, his most outspoken critic. But as he died Zechariah called out to the LORD to avenge his blood, which God did by sending the Arameans to attack the kingdom of Judah.

The book of Jubilees, which styles itself as revelation given to Moses of Israel’s entire history from the creation until the end of time, made the story of Joash’s infidelity paradigmatic for the entire people of Israel. Like Joash, the whole people would forsake the Temple and worship idols. Like Joash, all Israel would refuse to listen to the witnesses God sent to them. And like Joash, they would even go so far as to kill the prophets and persecute those who studied the Torah. Finally, all Israel would experience destruction and exile (it is the Babylonian exile to which Jubilees refers), just as the princes of the people had been destroyed by the Arameans in the days of King Joash.

Like Jubilees, the source from which Jesus quoted was probably a retelling of Israel’s history. Perhaps it was written in the form of a testament or an apocalypse.[15] But the pseudepigraphon was unlike Jubilees in two important respects. First, whereas Jubilees abstracted the events of Zechariah’s murder, distilling a pattern of disobedience→prophet sending→prophet killing→destruction that would become paradigmatic for Israel’s history writ large, the pseudepigraphical work from which Jesus quoted retained the specific details of Zechariah’s murder and even elaborated them by locating the precise spot in the Temple where Zechariah had been killed. Second, whereas Jubilees ostensibly dates from the time of Moses, the pseudepigraphon from which Jesus quoted probably presented itself as having been written shortly before the Babylonian exile. This (fictional) dating is suggested by the prophet sending→prophet killing→destruction pattern we observed in Jubilees. Although Jesus’ pseudepigraphon declined to abstract the details of the pattern, the pattern itself holds. Blood will be required from “this generation” not only for Zechariah’s murder but also for the shedding of all innocent blood since the murder of Abel. What generation in Israel’s history had endured punishment commensurate with such a magnitude of guilt? Only the generation that had experienced the destruction of Jerusalem and the exile to Babylon. Therefore, the generation the Wisdom of God addresses in Jesus’ pseudepigraphon must be identified as the generation that went into exile.

There are additional indications that the generation the Wisdom of God addresses in Jesus’ pseudepigraphon is the generation of the exile. The Torah stipulates that bloodshed defiles the sanctity of the land of Israel (Num. 35:33-34)[16] and that exile is a consequence of defiling the land (Lev. 18:24-28).[17] Moreover, 2 Kgs. 24:3-4 explicitly states that the spilling of innocent blood was the reason for the destruction of Jerusalem and the deportation of Judah’s population to Babylon.[18] In addition, post-Second Temple-period Jewish sources attribute the high casualties the Babylonians inflicted during the destruction of Jerusalem to the outstanding blood-debt Israel owed on account of the murder of Zechariah the priest.[19] Thus, the emphasis Jesus’ pseudepigraphon placed on innocent blood, especially that of Zechariah the priest, which defiled the holy land suggests that the generation it (ostensibly) addressed was none other than the generation that went into exile in Babylon.

Pseudepigraphical works that retell scriptural stories of the past were often written as commentaries on the present. The book of 4 Ezra, for instance, purports to tell the story of the scriptural Ezra’s struggle to come to terms with the destruction of Solomon’s Temple, but its actual purpose was to help its readers come to terms with the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E.[20] It seems likely, therefore, that although the pseudepigraphon from which Jesus quoted alluded to the Babylonian exile, its real purpose was to suggest that the generation to which the author of the pseudepigraphon belonged was just as guilty of bloodshed and just as deserving of punishment as the generation of the exile. By quoting this pseudepigraphical source, Jesus appropriated its message for his generation: because his generation had refused to renounce violence, it would be held responsible for all the innocent blood that had been spilled down through the ages.[21] And being responsible for so much bloodshed, Jesus’ generation could only anticipate catastrophic destruction. What the Babylonian Empire had done to the kingdom of Judah, Jesus’ generation would experience at the hands of the Roman Empire.

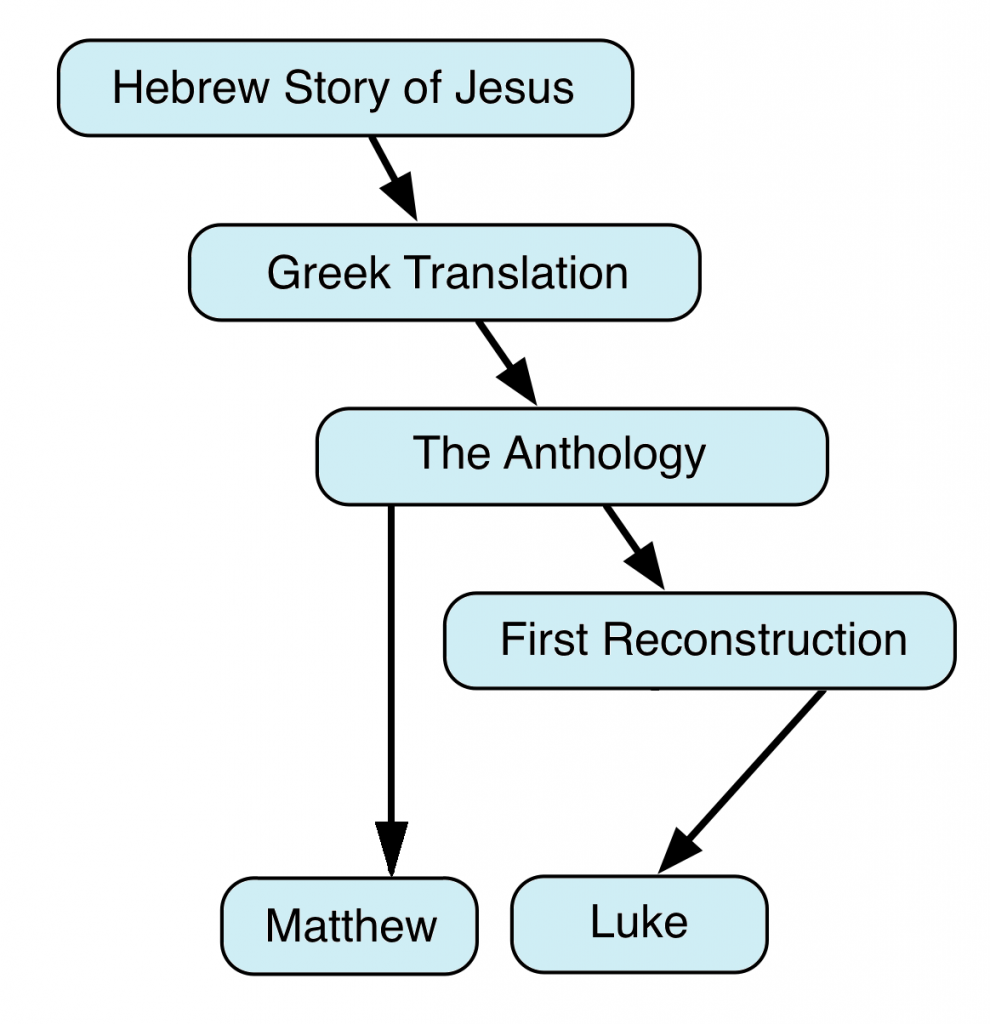

It is possible to discern that in Innocent Blood Jesus quoted a pseudepigraphical source in order to reapply its message to his own generation only because the author of Luke faithfully preserved the wording of his source. Three factors indicate that Luke’s source for Innocent Blood was the First Reconstruction (FR). First, as we noted in the Story Placement discussion above, the authors of Luke and Matthew agreed to link Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees and Innocent Blood in their respective Gospels. This common linkage suggests that these two pericopae were already united in their sources. Since Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees is a DT (Double Tradition) pericope characterized by low verbal agreement, it is probable that the author of Luke copied Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees from FR. And if the author of Luke copied Innocent Blood from the same source as Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees, it follows that the author of Luke probably copied Innocent Blood from FR too. Second, while much of the verbal disparity between the Lukan and Matthean versions of Innocent Blood must be attributed to pervasive Matthean redaction (see the Comment section below), some of the verbal disparity is probably due to the editorial activity of the First Reconstructor. Third, signs of Greek stylistic polishing in Innocent Blood (see below, Comment to L9, Comment to L16 and Comment to L24) are characteristic of the redactional work of the First Reconstructor.

Matthew’s version of Innocent Blood depends on the Anthology, the only source the author of Matthew and the author of Luke had in common.

A Christian addition to 4 Ezra contains a parallel to Innocent Blood:

Thus says the Lord Almighty: Have I not entreated you as a father entreats his sons or a mother her daughters or a nurse her children, that you should be my people and I should be your God, and that you should be my sons and I should be your father? I gathered you as a hen gathers her brood under her wings. But now, what shall I do to you? I will turn my face from you; for I have rejected your feast days, and new moons, and circumcisions of the flesh. I sent you my servants the prophets, but you have taken and slain them and torn their bodies in pieces; their blood I will require of you, says the Lord. (5 Ezra 1:28-32 [trans. Charlesworth, 1:526])

The allusion to Jesus’ Lament for Yerushalayim combined with the reworking of Innocent Blood in the Christian addition to 4 Ezra points to dependence on the Gospel of Matthew, in which these two pericopae appear adjacent to one another, but the vocabulary of “requiring blood” echoes the wording of Luke’s version of Innocent Blood. The reference to feast days and new moons which God rejects, on the other hand, is perversely reminiscent of the parallel to Innocent Blood in the book of Jubilees, in which Israel is censured for abandoning God’s festivals and sabbaths (Jub. 1:11).[22]

Crucial Issues

- What does Jesus’ use of a pseudepigraphical source tell us about his place in first-century Jewish society?

- Is the Innocent Blood pericope inherently anti-Jewish?

Comment

L1 διὰ τοῦτο (GR). Since both the Lukan and Matthean versions of Innocent Blood open with the words διὰ τοῦτο (dia touto, “on account of this,” “therefore”), we can be reasonably confident that this phrase also occurred in Anth. It is possible that the Anthologizer added διὰ τοῦτο in order to tie Innocent Blood to the preceding woe in Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees, but since Lindsey believed that the Anthologizer’s activities were restricted to rearranging the order in which pericopae appeared, we think it is more likely that διὰ τοῦτο was copied from the Greek translation of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

לְפִיכָךְ (HR). On reconstructing διὰ τοῦτο with לְפִיכָךְ (lefichāch, “therefore”), see Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry, Comment to L3. Some scholars have suggested that διὰ τοῦτο in L1 corresponds to Hebrew לָכֵן (lāchēn, “therefore”).[23] However, in Mishnaic Hebrew לָכֵן had given way to לְפִיכָךְ.[24] Since we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in a Mishnaic style of Hebrew, we have preferred the latter for HR.

L2 καὶ ἡ σοφία τοῦ θεοῦ εἶπεν (GR). As we stated in the Conjectured Stages of Transmission discussion above, Luke is surely correct in attributing the first person declaration concerning the sending of prophets and the requirement of blood in L3-23 to the Wisdom of God.[25] It is highly unlikely that the author of Luke, who exhibits no particular interest in personified Wisdom elsewhere in his Gospel or in Acts, would have attributed a saying of Jesus to the Wisdom of God.[26] The author of Matthew, on the other hand, had a strong motive for eliminating the attribution of L3-23 to the Wisdom of God and transferring them directly to Jesus: he wanted to transform Innocent Blood into a prediction of the tribulations the Matthean community had endured.[27]

אַף חָכְמַת אֱלֹהִים אָמְרָה (HR). On reconstructing καί (kai, “and”) with אַף (’af, “also”), see Return of the Twelve, Comment to L10. On reconstructing σοφία (sofia, “wisdom”) with חָכְמָה (ḥochmāh, “wisdom”), see Generations That Repented Long Ago, Comment to L13.

There is only a single instance of the phrase “wisdom of God” in the Hebrew Bible:

כִּי חָכְמַת אֱלֹהִים בְּקִרְבּוֹ לַעֲשׂוֹת מִשְׁפָּט

…for the wisdom of God [חָכְמַת אֱלֹהִים] was within him [i.e., Solomon] to do justice. (1 Kgs. 3:28)

ὅτι φρόνησις θεοῦ ἐν αὐτῷ τοῦ ποιεῖν δικαίωμα

…for the wisdom of God [φρόνησις θεοῦ] was in him to do justice. (3 Kgdms. 3:28)

The scriptural connection between the Wisdom of God and Solomon strengthens our suggested placement of Innocent Blood following Generations That Repented Long Ago, which makes reference to Solomon’s wisdom. Might the personified Wisdom of God be the “something greater” than Solomon’s wisdom referred to in Generations That Repented Long Ago? And might the prophecy of doom the Wisdom of God articulates be the “something greater” than Jonah’s prophecy of destruction?

On reconstructing θεός (theos, “god”) with אֱלֹהִים (’elohim, “God”), see Four Soils interpretation, Comment to L21.

Since in Innocent Blood Wisdom appears to be personified—as she is in the book of Proverbs (Prov. 1:20-33; 8:1-36; 9:1-12), Ben Sira (Sir. 24:1-22) and the Gospels (Matt. 11:19 ∥ Luke 7:35)—we have reconstructed εἶπεν (eipen, “he/she/it said”) with the feminine form אָמְרָה (’āmerāh, “she said”).

L3 ἀποστελῶ (GR). Although Matthew’s “Behold! I am sending…” looks Hebraic, it is likely to be redactional,[28] at least in Innocent Blood.[29] In Matthew’s Gospel the phrase ἰδοὺ ἐγὼ ἀποστέλλω (idou egō apostellō) occurs 3xx (Matt. 10:16; 11:10; 23:34). The first of these occurs in “The Harvest Is Plentiful” and “A Flock Among Wolves” (L49), which belongs to the Sending the Twelve discourse, where Jesus declares, “Behold! I am sending you like sheep among wolves” (Matt. 10:16 ∥ Luke 10:3). Since the author of Matthew transformed Innocent Blood into a prediction of persecutions to come, it is likely that he lifted ἰδοὺ ἐγὼ ἀποστέλλω out of “A Flock Among Wolves” and inserted it into Innocent Blood as a replacement for Anth.’s ἀποστελῶ (apostelō, “I will send”). That this was the author of Matthew’s procedure is especially likely given the other instances of borrowing from the Sending the Twelve discourse evident in his version of Innocent Blood (see below, Comment to L8, Comment to L9-10 and Comment to L12). We have therefore accepted Luke’s future tense ἀποστελῶ for GR.[30]

אֶשְׁלַח (HR). On reconstructing ἀποστέλλειν (apostellein, “to send”) with שָׁלַח (shālaḥ, “send”), see “The Harvest Is Plentiful” and “A Flock Among Wolves,” Comment to L49.

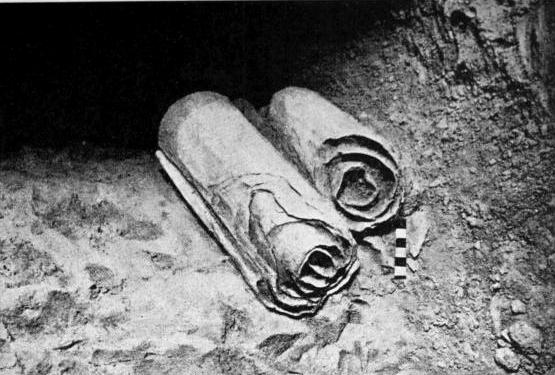

That the future tense is the best option for HR is confirmed by a Hebrew fragment of the passage of Jubilees that parallels the words spoken by the Wisdom of God in Innocent Blood:

ואשלחה אל[יהם] עדים ל[העיד…] ואת מבקשי[ ה]תורה ירדופ[ו …]

And I will send [ואשלחה] to [them] witnesses to[ witness…] and the seekers of [the ]Torah they will purs[ue….] (4QJuba [4Q216] II, 12-13)

L4 εἰς αὐτοὺς (GR). Not only did the author of Matthew change the speaker from the Wisdom of God to Jesus, he also changed the audience from the generation of the Babylonian exile to the scribes and Pharisees mentioned previously in Matthew 23. In order to effect this change, the author of Matthew, beginning in L4 and continuing through L24, changed the address from the third person (“they,” “them”) to the second person (“you”).[31] This change not only transferred the guilt for the murder of the innocents directly to the scribes and Pharisees, it also helped to integrate Innocent Blood into its Matthean context, in which the woes of Woes Against Scribes and Pharisees and Jesus’ Lament for Yerushalayim address the audience in the second person.[32] Luke’s third-person plural αὐτούς (avtous, “them”) preserves Anth.’s wording via FR.[33]

There is greater uncertainty regarding which preposition, Matthew’s πρός (pros, “to,” “toward”) or Luke’s εἰς (eis, “to,” “into”), is original. In the LXX translation of 2 Chr. 24:19 the preposition is πρός (καὶ ἀπέστειλεν πρὸς αὐτοὺς προφήτας [“and he sent to them prophets”]), but there is no reason to assume that the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua consulted the LXX translation of this verse. Luke’s εἰς, on the other hand, looks more like the preposition -בְּ (be–, “in”), which occurs in the Hebrew text of 2 Chr. 24:19 (וַיִּשְׁלַח בָּהֶם נְבִאִים [“and he sent in them prophets”]). Complicating the question is the parallel in Jub. 1:12, where the preposition in the Hebrew fragment is אֲלֵיהֶם (’alēhem) (ואשלחה אל[יהם] עדים [“and I will send to (them) witnesses”]; 4QJuba II, 12). Under these circumstances, either Matthew’s or Luke’s preposition could be original. However, since Matthew’s version of Innocent Blood is heavily redacted, we have accepted Luke’s εἰς for GR.

בָּהֶם (HR). As we noted above, Luke’s prepositional phrase εἰς αὐτούς (eis avtous, “into them”) looks like בָּהֶם (bāhem, “in them” or “against them”), which occurs in the Hebrew text of 2 Chr. 24:19, the verse upon which Wisdom’s declaration is based. Other options for HR are אֲלֵיהֶם (“to them”), which is supported by the Hebrew fragment of Jub. 1:12, and לָהֶם (lāhem, “to them”), which would be more typical of Mishnaic Hebrew. Usually when reconstructing direct speech we prefer a Mishnaic style of Hebrew, but here Jesus is quoting from a Second Temple source that paraphrased 2 Chr. 24:19.

L5 προφήτας καὶ ἀποστόλους (GR). Luke and Matthew agree to write “prophets,” but only Luke’s version has “apostles.” Many scholars regard Luke’s καὶ ἀποστόλους (kai apostolous, “and apostles”) as secondary on the grounds that “apostle” is a distinctively Christian term, and therefore the author of Luke was attempting to Christianize Innocent Blood by adding καὶ ἀποστόλους to his text.[34] However, a Christianizing tendency is not evident elsewhere in Luke’s version of Innocent Blood, and “apostle” is not an exclusively Christian term.[35] As we noted in Choosing the Twelve, Comment to L10-11, Greek and Latin sources use the terms ἀπόστολος/apostolos to refer to official messengers of the Jewish patriarch. These officers appear to be identical to the שְׁלִיחִים (sheliḥim, “messengers,” “emissaries”) of the nasi mentioned in rabbinic sources. Thus, supposing Luke’s ἀπόστολος reflects שָׁלִיחַ in the underlying Hebrew text, it is unwarranted to claim that the author of Luke has Christianized his source. Moreover, it appears that the author of Matthew avoided the term ἀπόστολος, which occurs only once in his Gospel (Matt. 10:2).[36] In view of these facts, we have accepted Luke’s καὶ ἀποστόλους for GR.

נְבִיאִים וּשְׁלִיחִים (HR). On reconstructing προφήτης (profētēs, “prophet”) with נָבִיא (nāvi’, “prophet”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L22.

While Wolter is correct in noting that the pairing of “prophet” and “apostle” is not attested in Jewish sources,[37] there is a rabbinic tradition according to which שָׁלִיחַ (“emissary”) is regarded as a synonym for “prophet”:

עשרה שמות נקרא נביא אלו הן. ציר. נאמן. עבד. שליח. חוזה. צופה. רואה. חלום. נביא. איש אלהים.

By ten names were prophets called, and they are: ambassador, faithful, servant, emissary [שָׁלִיחַ], visionary, watchman, seer, dreamer, prophet, man of God. (Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version A, 34:7 [ed. Schechter, 102])

Thus, Luke’s pairing of “prophet” and “apostle” is neither un-Jewish nor un-Hebraic.

On reconstructing ἀπόστολος (apostolos, “apostle”) with שָׁלִיחַ (shāliaḥ, “emissary”), see Choosing the Twelve, Comment to L10-11.

L6 καὶ σοφοὺς καὶ γραμματεῖς (GR). Many scholars believe that Matthew’s “sages and scribes” is original because these are distinctly Jewish terms and would not have been added by a Christian writer.[38] In fact, neither σοφός (sofos, “wise person,” “sage”) nor γραμματεύς (grammatevs, “scribe”) is distinctly Jewish. Both are professional terms that cross ethnic, religious and geo-political boundaries (cf. Acts 19:35; 1 Cor. 1:20). Scribes were professional copyists, accountants, archivists, etc., and wise men (sages) were academics, consultants, advisers, and the like.[39] Despite the misapprehension among New Testament scholars that the terms “sage” and “scribe” were uniquely Jewish terms, there are good reasons for regarding Matthew’s inclusion of these terms as original.

First, sages and scribes are strongly associated with wisdom,[40] therefore it is quite natural for the personified Wisdom of God to send sages and scribes along with prophets and apostles to rebuke those who had fallen into error.[41] Second, the author of Matthew shows no particular interest in sages (σοφοί [sofoi, “wise persons”]) elsewhere in his Gospel,[42] so it is unlikely he would have added the term here.[43] It is even more difficult to suppose that the author of Matthew added “scribes” to the list of Wisdom’s messengers, since the author of Matthew spent the better part of chapter 23 condemning the Pharisees and scribes.[44] Third, rabbinic sources portray the sages as the successors of the prophets,[45] so a similar idea may have been operative in the speech attributed to the Wisdom of God.[46]

More decisive than any of the previous arguments, however, is the parallel to Innocent Blood found in Jubilees:

| Jubilees 1:12 (trans. Charles) | Jesus’ Pseudepigraphon (reconstructed) |

| And I will send witnesses unto them, that I may witness against them, but they will not hear, and will slay the witnesses also, and they will persecute those who seek the law [מְבַקְּשֵׁי הַתּוֹרָה]. | I will send to them prophets and apostles and sages and scribes, and some of them they will kill, and some of them they will persecute. |

“Prophets and apostles” in the speech attributed to the Wisdom of God corresponds to the “witnesses” in Jubilees (cf. 2 Chr. 24:19), while “sages and scribes” corresponds (formally and conceptually) to “seekers of the Torah.”[47] This parallelism is so strong that it is impossible to dismiss Matthew’s “sages and scribes” as secondary.[48]

The First Reconstructor, whom Lindsey described as an epitomizer of Anth., probably eliminated “sages and scribes” in order to keep the focus of this pericope on the prophets. Thus, “sages and scribes” was likely absent in the source from which the author of Luke copied Innocent Blood.

וַחֲכָמִים וְסוֹפְרִים (HR). On reconstructing σοφός (sofos, “wise”) with חָכָם (ḥāchām, “wise”), see Yeshua’s Thanksgiving Hymn, Comment to L7.

On reconstructing γραμματεύς (grammatevs, “scribe”) with סוֹפֵר (sōfēr, “scribe”), see Call of Levi, Comment to L41.

The coupling of חָכָם with סוֹפֵר is attested in biblical and post-biblical sources:

אֵיכָה תֹאמְרוּ חֲכָמִים אֲנַחְנוּ וְתוֹרַת יי אִתָּנוּ אָכֵן הִנֵּה לַשֶּׁקֶר עָשָׂה עֵט שֶׁקֶר סֹפְרִים

How can you say, “We are sages [חֲכָמִים], and the Torah of the LORD is with us”? But behold! The false pen of the scribes [סֹפְרִים] has made it false. (Jer. 8:8)

πῶς ἐρεῖτε ὅτι σοφοί ἐσμεν ἡμεῖς, καὶ νόμος κυρίου ἐστὶν μεθ᾿ ἡμῶν; εἰς μάτην ἐγενήθη σχοῖνος ψευδὴς γραμματεῦσιν.

How will you say, “We are sages [σοφοί], and the Torah of the Lord is with us”? A false pen has become useless to the scribes [γραμματεῦσιν]. (Jer. 8:8)

ויהי דויד בן ישי חכם ואור כאור השמש וסופר ונבון ותמים בכול דרכיו לפני אל ואנשים

And David son of Jesse was a sage [חָכָם] and a light like the light of the sun and a scribe [סוֹפֵר] and prudent and perfect in all his ways before God and human beings. (11QPsa [11Q5] XXVII, 2-3)

אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹסֵי בֶּן קִסְמָא פַּעַם אַחַת הָיִיתִי מְהַלֵּךְ בַּדֶּרֶךְ וּפָּגַע בִּי אָדָם אֶחָד וְנָתַן לִי שָׁלוֹם וְהֶחֱזַרְתִּי לוֹ שָׁלוֹם אָמַר לִי רַבִּי מֵאֵיזֶה מָקוֹם אָתָּה אָמַרְתִּי לוֹ מֵעִיר גְּדוֹלָה שֶׁל חֲכָמִים וְשֶׁל סוֹפְרִים אָנִי

Rabbi Yose ben Kisma said, “On one occasion I was walking along the road, and a certain man met me. He gave me a greeting, and I returned a greeting to him. He said to me, ‘Rabbi, what place do you come from?’ I said, ‘From a great city of sages [חֲכָמִים] and scribes [סוֹפְרִים].’” (m. Avot 6:9 [ed. Blackman, 4:548])

איסי בן יהודה היה מונה שבחן של חכמים ר″מ חכם וסופר

Issi ben Yehudah would enumerate the talents of the sages. “Rabbi Meir is a sage [חָכָם] and a scribe [סוֹפֵר]….” (b. Sot. 67a)

עד שאדם מוטל גולם לפני מי שאמר והיה העולם הראה לו דור דור וחכמיו דור דור ושופטיו דור דור וסופריו ודורשיו ומנהיגיו

While Adam was still an unformed mass before the One who spoke and the world came into being, he showed him each generation and its sages [וחכמיו], each generation and its judges, each generation and its scribes [וסופריו] and its interpreters and its leaders. (Gen. Rab. 24:2 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 1:231])

L7 ἐξ αὐτῶν ἀποκτενοῦσιν (GR). The Lukan and Matthean versions of Innocent Blood are mainly in agreement in L7, except that Luke has the coordinating conjunction καί (kai, “and”) at the beginning of the phrase, and Matthew’s version has a direct accusation (“you will kill”) instead of the original third-person prediction (“they will kill”) preserved in Luke.[49] From GR we have omitted Luke’s καί,[50] since a conjunction in HR is not strictly necessary, although it is possible that καί is original.

מֵהֶם יַהֲרֹגוּ (HR). Scholars often point to the use of ἐξ αὐτῶν (ex avtōn, “[some] from them”) as the object of a verb as a Semitic[51] or Septuagintal[52] feature of the Innocent Blood pericope. This Hebraic usage likely reflects מֵהֶם (mēhem, “[some] from them”) in the underlying Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

On reconstructing ἀποκτείνειν (apokteinein, “to kill”) with הָרַג (hārag, “kill”), see Yohanan the Immerser’s Execution, Comment to L25.

The parallel to Innocent Blood in Jubilees suggests that the “some” who will be killed are to be identified with the first subset of those sent to Israel by the Wisdom of God, namely the prophets and emissaries, since according to Jub. 1:12 it is the witnesses (i.e., prophets) who are killed and the seekers of the Torah (parallel to the sages and scribes in Innocent Blood) who are persecuted.

The prophet-killing motif we encounter in Innocent Blood and Jubilees also occurs in other Second Temple Jewish sources including 1 Enoch and the Martyrdom of Isaiah.[53] The motif also surfaces in early Christian sources (cf., e.g., Matt. 23:37-39 ∥ Luke 13:34-35; 1 Thess. 2:14-16).

L8 καὶ σταυρώσετε (Matt. 23:34). “And you will crucify” is probably a Matthean addition to Innocent Blood,[54] since a parallel to this phrase is lacking in the Lukan version as well as in Jub. 1:12. Moreover, καὶ σταυρώσετε (kai stavrōsete, “and you will crucify”) is likely a reminiscence of Matt. 10:38 (καὶ ὃς οὐ λαμβάνει τὸν σταυρὸν αὐτοῦ [kai hos ou lambanei ton stavron avtou, “and whoever does not take his cross”]), since Matthew’s version of Innocent Blood is replete with echoes from Matthew chapter 10 (see above, Comment to L3, and below, Comment to L9-10 and Comment to L12).

L9-10 καὶ ἐξ αὐτῶν μαστειγώσετε ἐν ταῖς συναγωγαῖς ὑμῶν (Matt. 23:34). “You will scourge in your synagogues” is also to be regarded as a Matthean addition. This accusation echoes Matt. 10:17, which states, καὶ ἐν ταῖς συναγωγαῖς αὐτῶν μαστιγώσουσιν ὑμᾶς (kai en tais sūnagōgais avtōn mastigōsousin hūmas, “and in their synagogues they will scourge you”).[55] Note especially the dissociative language the author of Matthew employed in this accusation:[56] in the author of Matthew’s mind the synagogues belonged to others; he regarded himself and the members of his church as separate and distinct from the Jewish community.[57]

L9 καὶ ἐξ αὐτῶν (GR). Whereas the reference to synagogue whippings is likely to be redactional, Matthew’s καὶ ἐξ αὐτῶν (kai ex avtōn, “and [some] from them”) might preserve the wording of Anth.[58] As we noted above in Comment to L7, the use of ἐξ αὐτῶν as the object of a verb is Hebraic, and מֵהֶם, the Hebrew equivalent of ἐξ αὐτῶν, is required in HR. The First Reconstructor’s Greek polishing of Anth.’s wording is probably responsible for the omission of a second ἐξ αὐτῶν in Luke’s version of Innocent Blood.

מֵהֶם (HR). The following examples are comparable to our Hebrew Reconstruction in L9:

סמים מה סמים הללו מהן ירוקין מהן אדומים מהן שחורים מהם לבנים כך שמים פעמים ירוקין פעמים אדומים פעמים שחורים פעמים לבנים

Samim: pigments. Regarding pigments, some of them [מֵהֶן] are green, some of them [מֵהֶן] are red, some of them [מֵהֶן] are black, some of them [מֵהֶן] are white, so shamayim [the heavens] are sometimes green, sometimes red, sometimes black, sometimes white. (Gen. Rab. 4:7 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 1:31])

בשעה שבא הקב″ה לבראת את אדם הראשון נעשו מלאכי השרת כיתים וחבורות חבורות, מהם אומרים יברא מהם אומרים אל יברא

When the Holy One, blessed be he, was about to create the first human, the ministering angels formed factions and companies. Some of them [מֵהֶם] were saying, “Let him be created!” Some of them [מֵהֶם] were saying, “Let him not be created!” (Gen. Rab. 8:5 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 1:60])

אין בהם פסולת אלא מהם בעלי מקרא מהם בעלי משנה מהם בעלי תלמוד מהם בעלי אגדה

…there is no waste material among them. Rather, some of them [מֵהֶם] are masters of Scripture, some of them [מֵהֶם] are masters of Mishnah, some of them [מֵהֶם] are masters of Talmud, some of them [מֵהֶם] are masters of Aggadah. (Gen. Rab. 41:1 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 1:388])

Although the conjunction καί (“and”) probably occurred in Anth., the above-cited examples demonstrate that a corresponding conjunction in Hebrew is unnecessary. Thus, καί in L9 was likely a stylistic concession of the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua to the demands of Greek style.

L11 διώξουσιν (GR). Both Luke and Matthew have forms of the verb διώκειν (diōkein, “to pursue”) in L11. Matthew’s second-person plural form διώξετε (diōxete, “you will pursue”) reflects his redactional program of transforming the Wisdom of God’s speech into Jesus’ accusation against the Pharisees. Luke’s third-person plural form διώξουσιν (diōxousin, “they will pursue”) preserves Anth.’s wording via FR.

יִרְדֹּפוּ (HR). In LXX most instances of διώκειν (“to pursue”) occur as the translation of רָדַף (rādaf, “pursue”).[59] We also find that the LXX translators rendered most instances of רָדַף with διώκειν or related compound verbs.[60] Our selection of רָדַף for HR is corroborated by the Hebrew fragment of Jub. 1:12, which reads: ואת מבקשי[ ה]תורה ירדופ[ו …] (“and the seekers of Torah they will pursue”; 4QJuba II, 13). The Jubilees fragment also suggests that it is the second subset of those whom the Wisdom of God sends (i.e., sages and scribes) who will be pursued.

L12 ἀπὸ πόλεως εἰς πόλιν (Matt. 23:34). The reference to persecution probably reminded the author of Matthew of Jesus’ instructions in Matt. 10:23, which state: ὅταν δὲ διώκωσιν ὑμᾶς ἐν τῇ πόλει ταύτῃ φεύγετε εἰς τὴν ἑτέραν (hotan de diōkōsin hūmas en tē polei tavtē fevgete eis tēn heteran, “when they pursue you in this city, flee to the other”).[61] This recollection inspired the author of Matthew to write ἀπὸ πόλεως εἰς πόλιν (apo poleōs eis polin, “from city to city”) in L12.[62]

L13 ὅπως ἔλθῃ ἐφ᾿ ὑμᾶς (Matt. 23:35). In L13 the author of Matthew continued his practice of changing the address to the second person plural so as to inculpate the Pharisees for the killing of the prophets and the murder of the innocent. The author of Matthew composed the words ὅπως ἔλθῃ ἐφ᾿ ὑμᾶς πᾶν αἷμα (hopōs elthē ef hūmas pan haima, “so that all the blood might come upon you”; L13-14) in order to foreshadow the uniquely Matthean (and clearly redactional) scene in the passion narrative where Pontius Pilate washes his hands and declares himself to be innocent of Jesus’ blood, and the Jewish mob affirms Pilate’s innocence with the words τὸ αἷμα αὐτοῦ ἐφ᾿ ἡμᾶς καὶ ἐπὶ τὰ τέκνα ἡμῶν (to haima avtou ef hēmas kai epi ta tekna hēmōn, “His blood be upon us and upon our children!”; Matt. 27:25).[63] As we will discuss below, it is Luke’s version that preserves Anth.’s wording in L13 via FR.

Hagner supposed that Matthew’s “all the blood might come upon you” is original because it reflects the scriptural idiom of blood being on one’s head,[64] but the head metaphor is conspicuously absent from Matthew’s wording. Nolland more cogently suggested that Matthew’s wording must be original because it preserves a non-Septuagintal Hebraism reflecting נָתַן דָּם עַל (nātan dām ‘al, “put blood upon”), used in the sense of “make responsible for the blood of” in the following examples:[65]

אַךְ יָדֹעַ תֵּדְעוּ כִּי אִם מְמִתִים אַתֶּם אֹתִי כִּי דָם נָקִי אַתֶּם נֹתְנִים עֲלֵיכֶם

But know full well that if you kill me, you are putting innocent blood upon yourselves [i.e., making yourselves responsible for my innocent blood—DNB and JNT]…. (Jer. 26:15)

ἀλλ᾿ ἢ γνόντες γνώσεσθε ὅτι, εἰ ἀναιρεῖτέ με, αἷμα ἀθῷον δίδοτε ἐφ᾿ ὑμᾶς

But knowing you will know that if you kill me, you are putting innocent blood on yourselves…. (Jer. 33:15)

וַיִּקְרְאוּ אֶל יי וַיֹּאמְרוּ אָנָּה יי אַל נָא נֹאבְדָה בְּנֶפֶשׁ הָאִישׁ הַזֶּה וְאַל תִּתֵּן עָלֵינוּ דָּם נָקִיא

And they [i.e., the men on Jonah’s ship—DNB and JNT] cried to the LORD and said, “Please, LORD, please do not let us perish because of the life of this man, and do not put innocent blood on us [i.e., do not make us responsible for Jonah’s blood—DNB and JNT]….” (Jonah 1:14)

καὶ ἀνεβόησαν πρὸς κύριον καὶ εἶπαν Μηδαμῶς, κύριε, μὴ ἀπολώμεθα ἕνεκεν τῆς ψυχῆς τοῦ ἀνθρώπου τούτου, καὶ μὴ δῷς ἐφ᾿ ἡμᾶς αἷμα δίκαιον

And they cried to the Lord and said, “Let it not be, Lord! Do not let us be destroyed on account of the life of this man, and do not put on us innocent blood….” (Jonah 1:14)

We note, however, that putting blood on oneself (as in Jer. 26:15) and putting blood on someone else (as in Jonah 1:14) is rather different than blood coming upon someone of its own accord (as in Matt. 23:35). This (by no means insignificant) distinction stretches the credibility of the non-Septuagintal Hebraism Nolland believed he had discovered. To our mind it is unnecessary to search for a Semitic background to Matthew’s wording in L13;[28] a grammatical parallel occurs in the Gospel of John:

Ιησοῦς οὖν εἰδὼς πάντα τὰ ἐρχόμενα ἐπ᾿ αὐτὸν ἐξῆλθεν καὶ λέγει αὐτοῖς· τίνα ζητεῖτε;

Therefore Jesus, knowing all the [things] coming upon him [πάντα τὰ ἐρχόμενα ἐπ᾿ αὐτὸν], went out and he says to them, “Whom are you seeking?” (John 18:4)

As in Matt. 23:35, so in John 18:4, something (Matt.: blood; John: unspecified happenings) comes upon someone (or some group of persons) to his (or their) great detriment.

If a scriptural background for Matthew’s vocabulary in L13 must be sought, then it is possible that the author of Matthew hoped to echo the threats in Deuteronomy that if Israel is disobedient, ἐλεύσονται ἐπὶ σὲ πᾶσαι αἱ κατάραι αὗται (“all these curses will come upon you”; Deut. 28:15, 45; cf. Deut. 30:1).

ἵνα ἐκζητηθῇ (GR). Luke’s ἵνα ἐκζητηθῇ (hina ekzētēthē, “so that it might be required”) is a clear allusion to the story of the murder of Zechariah in the Temple:[66]

וּכְמוֹתוֹ אָמַר יֵרֶא יי וְיִדְרֹשׁ

And as he [i.e., Zechariah—DNB and JNT] died, he said, “Let the LORD see and require [it]!” (2 Chr. 24:22)

καὶ ὡς ἀπέθνῃσκεν, εἶπεν Ἴδοι κύριος καὶ κρινάτω

And as he died, he said, “May the Lord see and judge!” (2 Chr. 24:22)

Note, however, that the allusion to 2 Chr. 24:22 is not based on LXX! If a reader of the LXX version of the story asked herself, “What was it that Zechariah wanted God to do?” she would probably conclude that Zechariah wanted God to witness the fact of his murder and deliver justice. Nothing in the LXX version suggests that Zechariah wanted God to see his blood or demand his blood from his killers. But if a reader of the Hebrew text asked himself the same question, he might very well conclude that it was precisely his blood that Zechariah wanted God to see and to demand from his killers. The focus on blood is not explicit in the Hebrew text of 2 Chr. 24:22, but it is suggested by the idiom דָּרַשׁ דָּם (dārash dām, “demand blood,” i.e., “hold someone responsible for another’s death”). It would be a reasonable inference for any Hebrew speaker familiar with the idiom דָּרַשׁ דָּם to conclude that וְיִדְרֹשׁ (veyidrosh, “and let him demand”) referred specifically to Zechariah’s blood.[67]

Since the author of Luke had no knowledge of Hebrew, he had no way of knowing that Zechariah’s dying request referred to seeing and demanding his blood. Therefore, he had no motive for writing “so that the blood might be demanded.” Without knowledge of Hebrew the author of Luke could not even have detected the allusion to 2 Chr. 24:22 in L13.[68] It staggers the mind to suppose that the author of Luke accidentally created an allusion to 2 Chr. 24:22. Moreover, ἐκζητεῖν ἀπό (ekzētein apo, “to seek out from”) in the sense of “hold accountable for” is not a normal Greek expression.[69] The only reasonable conclusion is that the words ἵνα ἐκζητηθῇ came from Luke’s source.[70]

וְיִדָּרֵשׁ (HR). The Greek construction ἵνα + subjunctive typically indicates purpose (“so that”), but it can also be used to indicate consequence (“with the result that”),[71] which is the most likely meaning here.[72] In LXX ἵνα + subjunctive often occurs as the translation of -וְ + imperfect.[73] The following examples are illustrative of this pattern:

שֵׁשֶׁת יָמִים תַּעֲשֶׂה מַעֲשֶׂיךָ וּבַיּוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי תִּשְׁבֹּת לְמַעַן יָנוּחַ שׁוֹרְךָ וַחֲמֹרֶךָ וְיִנָּפֵשׁ בֶּן־אֲמָתְךָ וְהַגֵּר

Six days you will do your work, but on the seventh day you will rest, so that your ox and your donkey may rest, and your maidservant’s son and the sojourner may be refreshed [וְיִנָּפֵשׁ]. (Exod. 23:12)

ἓξ ἡμέρας ποιήσεις τὰ ἔργα σου, τῇ δὲ ἡμέρᾳ τῇ ἑβδόμῃ ἀνάπαυσις, ἵνα ἀναπαύσηται ὁ βοῦς σου καὶ τὸ ὑποζύγιόν σου, καὶ ἵνα ἀναψύξῃ ὁ υἱὸς τῆς παιδίσκης σου καὶ ὁ προσήλυτος

Six days you will do your work, but the seventh day is a respite, so that your ox and your beast of burden may rest, and so that [ἵνα] your maidservant’s son and the proselyte may be refreshed [ἀναψύξῃ]. (Exod. 23:12)

וּמָשַׁחְתָּ אֹתָם וּמִלֵּאתָ אֶת־יָדָם וְקִדַּשְׁתָּ אֹתָם וְכִהֲנוּ לִי

And you will anoint them and fill their hand and sanctify them, and they will be priests [וְכִהֲנוּ] for me. (Exod. 28:41)

καὶ χρίσεις αὐτοὺς καὶ ἐμπλήσεις αὐτῶν τὰς χεῖρας καὶ ἁγιάσεις αὐτούς, ἵνα ἱερατεύωσίν μοι

And you will anoint them and fill their hands and sanctify them, so that they will be priests [ἵνα ἱερατεύωσίν] to me. (Exod. 28:41)

We believe Luz was on the right track when he asked whether ἵνα ἐκζητηθῇ (hina ekzētēthē, “so that it might be demanded”) echoes וְיִדְרֹשׁ (veyidrosh, “and let him require it”) in 2 Chr. 24:22.[74] In LXX ἐκζητεῖν (ekzētein, “to seek out”) usually occurs as the translation of either דָּרַשׁ (dārash, “seek,” “demand”) (about 70xx) or בִּקֵּשׁ (biqēsh, “seek,” “ask”) (about 30xx).[75] We also find that the LXX translators rendered דָּרַשׁ more often with ἐκζητεῖν than with any other verb.[76] Moreover, the LXX translators rendered דָּרַשׁ with ἐκζητεῖν in each of the four scriptural instances of דָּרַשׁ דָּם (dārash dām, “demand blood”; Gen. 9:5; 42:22; Ezek. 33:6; Ps. 9:13).[77]

Luke’s passive ἐκζητηθῇ (“might be sought out”) indicates that in L13 the root [no_word_wrap]ד-ר-ש[/no_word_wrap] should occur in the nif ‘al stem. An example of נִדְרַשׁ (nidrash, “be demanded”) occurs in the story of Joseph and his brothers:

וַיַּעַן רְאוּבֵן אֹתָם לֵאמֹר הֲלוֹא אָמַרְתִּי אֲלֵיכֶם לֵאמֹר אַל־תֶּחֶטְאוּ בַיֶּלֶד וְלֹא שְׁמַעְתֶּם וְגַם־דָּמוֹ הִנֵּה נִדְרָשׁ

And Reuben answered them saying, “Did I not say to you, ‘Do not sin by this boy’? But you did not listen. And also his blood, behold, it is being demanded [נִדְרָשׁ; LXX: ἐκζητεῖται].” (Gen. 42:22)

L14 πᾶν αἷμα δίκαιον (GR). Whereas Luke’s version refers to “the blood of all the prophets,” Matthew’s version refers to “all [the] righteous blood.” There are several reasons that lead us to suppose that in this case Matthew’s version is more original than Luke’s.[78] First, it is strange that the Wisdom of God, having sent prophets, emissaries, sages and scribes, should hold the perpetrators responsible for the blood of the prophets only, and not for the blood of the others. Second, Abel was not regarded as a prophet in ancient Jewish sources.[79] Some ancient traditions may have regarded Abel as a proto-priest on account of the acceptable sacrifices he offered (Gen. 4:4),[80] but Luke’s version of Innocent Blood is the only ancient source to suggest that Abel was a prophet.[81] Abel’s non-prophetic status, therefore, makes him highly unsuitable as an example of a prophet whose blood will be required. Third, it is unlikely that the author of Matthew would have deleted “all the blood of the prophets” from Innocent Blood had it occurred in his source. Such a deletion by the author of Matthew is improbable because the phrase “blood of the prophets” occurs in Matthew’s version of the preceding woe, where the Pharisees are said to claim that they would not have participated ἐν τῷ αἵματι τῶν προφητῶν (en tō haimati tōn prophētōn, “in the blood of the prophets”; Matt. 23:30). The author of Matthew took extensive measures in Innocent Blood to strengthen the ties to the preceding woes against the Pharisees, changing the speaker to Jesus by dropping the reference to the Wisdom of God (L2), changing the tense of ἀποστέλλειν from future to present (L3), changing the address to the second person in order to make the Pharisees the prophet-killers (L4, L7, L8, L9, L10, L11, L13, L21), and importing the verb φονεύειν (fonevein, “to murder”; L21) from the preceding woe in Matt. 23:31 (see below, Comment to L21). Having taken such pains, it is unlikely that the author of Matthew would have weakened the ties between Innocent Blood and the preceding woes by changing “blood of the prophets” had it occurred in his source. Fourth, Matthew’s πᾶν αἷμα δίκαιον (pan haima dikaion, “all [the] righteous blood”) reverts easily to Hebrew (see below) and makes good sense in this pericope. Those who killed the prophets and emissaries will be held accountable not only for this misdeed but for every instance of wrongful bloodletting since history began.

We suspect that it was either the First Reconstructor or the author of Luke who wrote τὸ αἷμα πάντων τῶν προφητῶν (to haima pantōn tōn profētōn, “the blood of all the prophets”) in place of Anth.’s πᾶν αἷμα δίκαιον (“all [the] righteous blood”), having picked up “blood of the prophets” from Anth.’s version of the preceding woe (cf. Matt. 23:30).[82]

כָּל דָּם נָקִי (HR). On reconstructing πᾶς (pas, “all,” “every”) with כָּל (kol, “all,” “every”), see Demands of Discipleship, Comment to L32.

On reconstructing αἷμα (haima, “blood”) with דָּם (dām, “blood”), see Calamities in Yerushalayim, Comment to L5.

The LXX translators rendered the phrase כָּל דָּם (kol dām, “all blood”) as πᾶν (τὸ) αἷμα (pan [to] haima, “all [the] blood”) in Lev. 3:17; 4:7, 30, 34; 7:26; 17:10; 4 Kgdms. 16:15.

The LXX translators usually rendered the phrase דָּם נָקִי (dām nāqi, “innocent blood”) as αἷμα ἀναίτιον (haima anaition, “innocent blood”; Deut. 19:10, 13; 21:8, 9) or αἷμα ἀθῷον (haima athōon, “innocent blood”; Deut. 27:25; 1 Kgdms. 19:5; 4 Kgdms. 21:16; 24:4 [2xx]; Ps. 93[94]:21; 105[106]:38; Jer. 7:6; 19:4; 22:3, 17; 33[26]:15), but occasionally they rendered דָּם נָקִי as αἷμα δίκαιον (haima dikaion, “righteous blood”; Prov. 6:17; Joel 4:19; Jonah 1:14). Had the author of Matthew intended to imitate LXX usage, we would have expected him to choose either αἷμα ἀθῷον (the most common) or αἷμα ἀναίτιον (perhaps the most familiar because of its frequency in Deuteronomy). Matthew’s αἷμα δίκαιον (“righteous blood”) looks more like a direct translation from a Hebrew source than a Septuagintism.

The complete phrase כָּל דָּם נָקִי (kol dām nāqi, “all [the] innocent blood”) that we have adopted for HR is not attested in the Hebrew Bible, DSS or rabbinic sources. It does occur, however, in the writings of Rabbi David Kimhi (1160-1235 C.E.):

כי הנה ה′ יוצא ממקומו. על דרך משל כמו שאמר גם כן ויצא ה′ ונלחם בגוים ההם וכל עונם שקדם יפקד עליהם בעת ההיא וכל דם נקי ששפכו יפקד עליהם

For behold! The LORD is going out from his place [to visit the sin of the inhabitants of the land upon them. And the land will reveal its blood and will no longer cover its slain] [Isa. 26:21]. “Going out from his place” is a metaphor, as when it also says, And the LORD will go out and battle against those nations [Zech. 14:3]. And all their iniquity that was before he will visit upon them at that time. And all [the] innocent blood [וְכָל דָּם נָקִי] that they shed he will visit upon them. (Commentary on Isaiah 26:20 [ed. Finkelstein, 153])[83]

It is useful to note that according to a rabbinic tradition Zechariah’s blood is termed דָּם נָקִי:

שבע עבירות עברו ישראל באותו היום הרגו כהן ונביא ודיין ושפכו דם נקי וטימאו את העזרה ושבת ויום הכיפורים היה

With seven transgressions Israel transgressed in that day [i.e., the day of Zechariah’s murder—DNB and JNT]: they killed a priest and a prophet and a judge, and they poured out innocent blood [דָּם נָקִי], and they made the court [of the Temple] impure, and it was a Sabbath and the Day of Atonement. (y. Taan. 4:5 [25a])

|

The second-century B.C.E. tombstone of a murdered Jewish girl from Delos pictured to the right bears the following inscription:

|

L15 ἐκχυννόμενον (GR). Since Luke’s τὸ ἐκκεχυμένον (to ekkechūmenon, “that which was poured out”) looks like an adaptation of Anth.’s wording to accommodate τὸ αἷμα πάντων τῶν προφητῶν (“the blood of all the prophets”; L14), we have accepted Matthew’s participle ἐκχυννόμενον (ekchūnnomenon, “being poured out”) for GR.

שָׁפוּךְ (HR). In LXX most instances of ἐκχεῖν (ekchein, “to pour out”) occur as the translation of שָׁפַךְ (shāfach, “pour out”).[85] Likewise, the LXX translators rendered most instances of שָׁפַךְ with ἐκχεῖν.[86] The passive participle שָׁפוּךְ (shāfūch, “poured out”) corresponds to the participial form of ἐκχεῖν adopted for GR. Compare our reconstruction to the following example from the Psalms:

לָמָּה יֹאמְרוּ הַגּוֹיִם אַיֵּה אֱלֹהֵיהֶם יִוָּדַע בגיים [בַּגּוֹיִם] לְעֵינֵינוּ נִקְמַת דַּם עֲבָדֶיךָ הַשָּׁפוּךְ

Why must the Gentiles say, “Where is their god?” Let the vengeance of the poured out [הַשָּׁפוּךְ] blood of your servants be made known to the Gentiles before our eyes! (Ps. 79:10)

μήποτε εἴπωσιν τὰ ἔθνη Ποῦ ἐστιν ὁ θεὸς αὐτῶν; καὶ γνωσθήτω ἐν τοῖς ἔθνεσιν ἐνώπιον τῶν ὀφθαλμῶν ἡμῶν ἡ ἐκδίκησις τοῦ αἵματος τῶν δούλων σου τοῦ ἐκκεχυμένου

…lest the Gentiles say, “Where is their god?” And let it be known among the Gentiles before our eyes the vengeance of the poured out [τοῦ ἐκκεχυμένου] blood of your servants. (Ps. 78:10)

L16 ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς (GR). Matthew’s ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς (epi tēs gēs, “upon the earth”), which reverts easily to Hebrew, appears to reflect a typically Jewish concern for the ritual purity and sanctity of the holy land.[87] Luke’s ἀπὸ καταβολῆς κόσμου (apo katabolēs kosmou, “from the foundation of the world”), on the other hand, occurs in Greek compositions (John 17:24; Eph. 1:4; Heb. 4:3; 9:26; 1 Peter 1:20)[88] and is relatively difficult to reconstruct in Hebrew.[89] Moreover, the author of Matthew used the phrase ἀπὸ καταβολῆς κόσμου elsewhere in his Gospel (Matt. 13:35; 25:34), so there is no reason to suppose that he would have rejected it here.[90] It therefore seems likely that the First Reconstructor wrote “from the foundation of the world” in place of Anth.’s “upon the earth.”[91] Attributing “from the foundation of the world” to FR answers the objection that ἀπὸ καταβολῆς κόσμου is not Lukan vocabulary.[92] Thus, “on the earth” likely reflects the wording of Matthew’s source,[93] and we have accordingly accepted ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς for GR.

עַל הָאָרֶץ (HR). On reconstructing ἐπί (epi, “upon”) with עַל (‘al, “upon”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L11.

On reconstructing γῆ (gē, “earth,” “land”) with אֶרֶץ (’eretz, “land,” “earth”), see Sending the Twelve: Conduct in Town, Comment to L118.

L17 ἀπὸ τῆς γενεᾶς ταύτης (GR). The author of Matthew, who changed the address to the second person plural, was obliged to omit “from this generation” in L17.[94] Luke’s inclusion of this phrase is certainly original.[95]

מִיַּד הַדּוֹר הַזֶּה (HR). In Hebrew, when blood is demanded from someone, “from” is usually expressed as מִיָּד (miyād, “from [the] hand”).[96] The LXX translators usually rendered מִיָּד literally as ἐκ (τῆς) χειρός (ek [tēs] cheiros, “from [the] hand”) or ἐκ (τῶν) χειρῶν (ek [tōn] cheirōn, “from [the] hands”).[97] Less frequently the LXX translators rendered מִיָּד as ἀπὸ (τῆς) χειρός (apo [tēs] cheiros, “from [the] hand”) or ἀπὸ (τῶν) χειρῶν (apo [tōn] cheirōn, “from [the] hands”).[98] In other instances, however, the LXX translators did not render מִיָּד literally, but preferred simply to use a preposition such as παρά (para, “from”),[99] ἐκ (ek, “from”)[100] or ἀπό (apo, “from”).[101] There are even a very few instances in which the LXX translators altogether omitted an equivalent to מִיָּד, as we see in the following example:

וּבִקֵּשׁ יי מִיַּד אֹיְבֵי דָוִד

…and may the LORD seek [recompense] from the hand of the enemies of David. (1 Sam. 20:16)

καὶ ἐκζητήσαι κύριος ἐχθροὺς τοῦ Δαυιδ

…and may the Lord seek out the enemies of David. (1 Kgdms. 20:16)[102]

Given the tendency of Greek translators to sometimes give non-literal translations of מִיָּד, and in view of the normal Hebrew idiom “demand blood from the hand,” we feel justified in reconstructing ἀπό in L17 as מִיָּד.

On reconstructing γενεά (genea, “generation”) with דּוֹר (dōr, “generation”), see Generations That Repented Long Ago, Comment to L10. The phrase “this generation” forms a verbal link between Generations That Repented Long Ago (L10, L17) and Innocent Blood (L17, L26).

Manson was probably correct when he observed that the theme of repentance lies just below the surface of this saying.[103] Had Israel repented of its violence, “this generation” would have been spared. Thus, the theme of repentance inherent in the Innocent Blood pericope forms another bond linking it to Generations That Repented Long Ago, as well as to Sign-Seeking Generation, which is the pericope that follows Innocent Blood in the reconstructed “Choose Repentance or Destruction” complex. In all likelihood, the generation the Wisdom of God addressed was (ostensibly) the generation of the Babylonian exile. Nevertheless, Jesus believed her words had continuing relevance for the generation to which he belonged.

L18 ἀπὸ αἵματος Ἅβελ (GR). It is likely that the author of Matthew added the definite article τοῦ (tou, “the”) before αἵματος (haimatos, “blood”), since the omission of the definite article, as in Luke’s version, is more Hebraic.[104] Likewise, the author of Matthew was probably responsible for adding the title τοῦ δικαίου (tou dikaiou, “the righteous”) to Abel’s name.[105] Although Turnage has noted that certain ancient Jewish sources describe Abel as δίκαιος (dikaios, “righteous”; Philo., Q.G. 1:59; Jos., Ant. 1:53),[106] this appears to be a Hellenistic Jewish convention. There are no rabbinic sources that refer to Abel as הֶבֶל הַצַּדִּיק (hevel hatzadiq, “Abel the Righteous”), nor do we find this designation in DSS. We have therefore accepted Luke’s wording in L18 for GR.

מִדַּם הֶבֶל (HR). On reconstructing αἷμα (haima, “blood”) with דָּם (dām, “blood”), see above, Comment to L14.

In Innocent Blood Abel’s name is given as Ἅβελ (Habel), the form we also encounter in LXX as the transliteration of הֶבֶל (hevel).[107] When Josephus referred to Abel he preferred to use the Hellenized form Ἄβελος (Abelos; Ant. 1:52, 53, 54, 55, 67).

The phrase “blood of Abel” is not common in Hebrew sources, but examples such as the following do occur:

נטית ימינך מגיד שהים זרקן ליבשה והיבשה זורקן לים אמרה היבשה ומה אם בשעה שלא קבלתי אלא דמו של הבל שהוא יחיד נאמר לי ועתה ארור אתה מן האדמה וגו′ ועכשיו האיך אני יכולה לקבל דמן של אוכלוסין הללו

You stretched out your right hand [Exod. 15:12]. This tells us that the sea was throwing them [i.e., the bodies of the drowned Egyptians—DNB and JNT] to the dry land, and the dry land was throwing them to the sea. The dry land said, “Now if when I received the blood of Abel [דָּמוֹ שֶׁל הֶבֶל], who was but a single [person], it was said of me, Cursed are you from the ground [Gen. 4:11] etc., how will I now be able to receive the blood of these crowds?” (Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Shirata §9 [ed. Lauterbach, 212])

Peels supposed that in Innocent Blood the figures of Abel and Zechariah were not merely opposed to one another temporally by standing at the beginning and end of a violent history, he suggested that they were contrasted in other ways: “Abel was murdered in secret, in the field, far away from the altar, and without a witness. Zechariah was openly murdered by the altar, in public, on orders from the chief justice.”[108] We wonder, however, whether the author of the Wisdom of God’s words quoted in Innocent Blood was more impressed by what these two figures were believed to have had in common. As we noted in Comment to L14, Abel may have been regarded as a proto-priest, and it is even possible that the altar upon which Abel presented his offering was understood to have occupied the same location as the altar in the Temple in Jerusalem, just as the altar upon which Isaac was bound was believed to have been built on the Temple Mount.[109] If Abel’s blood was spilled on the future site of the Temple, it is all the more appropriate that his blood would be demanded of those who continued to do violence in and around the Temple.

L19 ἕως αἵματος Ζαχαρίου (GR). As in L18, the author of Matthew is probably responsible for adding the definite article τοῦ before αἵματος.[110] Most New Testament scholars suggest that Zechariah is mentioned because his is the last murder to be mentioned in Scripture according to the order of the books in the Jewish Bible, which places the books of Chronicles at the end.[111] Thus, “from Abel to Zechariah” spans all the murders in Scripture “from A to Z”[112] and “from cover to cover.”[113] The difficulty with this suggestion is that it anachronistically projects the concept of “Bible” back into the Second Temple period.[114] In Jesus’ time there was no such thing as a Bible as we conceive of it today, in which the entirety of Scripture was collected into a single omnibus. Scripture was not thought of as a single book, but as a library made up of diverse scrolls. There is evidence to suggest that scrolls containing the entire Torah were common in the Second Temple period, and scrolls containing the twelve minor prophets also existed.[115] But there were certainly no scrolls that began with Genesis and ended with 2 Chronicles and included everything else in between.[116]

Even if the practical impossibility of creating such a massive scroll could have been overcome, no scroll could have encompassed the entirety of Scripture, since the discussion concerning which books belonged to the sacred library of Scripture and which books did not was still ongoing at the end of the Second Temple period and beyond.[117] Given the historical circumstances, it is not at all clear that it is even possible to refer to an “order” of the Jewish Scriptures in the time of Jesus. As the Scriptures were a collection of scrolls, it is more likely that they were held in particular groupings (Torah, Prophets, Writings) than that they had any set order.[118] Therefore, it is dubious whether the position the books of Chronicles occupied in the library of Scripture had any bearing on the selection of the figures of Abel and Zechariah in the words attributed to the Wisdom of God.[119] More important to the singling out of Abel and Zechariah are their similarities: both served in a priestly capacity, both were murdered (possibly in the same location), and Abel’s blood cried out for vengeance while Zechariah cried out for his blood to be avenged.[120]

וְעַד דַּם זְכַרְיָה (HR). Although nothing in the Greek text supports the inclusion of the conjunction -וְ (ve–, “and”) prefixed to עַד (‘ad, “until”), in our reconstruction we have added the conjunction to HR because, as we noted in The Kingdom of Heaven Is Increasing, Comment to L6, numerous examples of עַד→מִן in MT have the coordinating conjunction -וְ prefixed to עַד.[122] There we also noted that the LXX translators frequently omitted an equivalent to -וְ when they rendered וְעַד→מִן constructions into Greek. Therefore, we feel justified in adding the conjunction -וְ to HR despite its lack of support in the Greek text.

On reconstructing ἕως (heōs, “until”) with עַד (‘ad, “until”), see Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, Comment to L22.

On reconstructing the name Ζαχαρίας (Zacharias, “Zechariah”) as זְכַרְיָה (zecharyāh, “Zechariah”), see A Voice Crying, Comment to L27.

L20 υἱοῦ Βαραχίου (Matt. 23:35). Matthew’s description of Zechariah as υἱοῦ Βαραχίου (huiou Barachiou, “son of Berechiah”) has generated a great deal of scholarly discussion because it conflicts with the scriptural account in 2 Chr. 24:19-22, in which the priest Zechariah is identified as the “son of Jehoiada” (MT: בֶּן יְהוֹיָדָע [ben yehōyādā‘]; LXX: τοῦ Ιωδαε [tou Iōdae]). The explanations scholars have given for this discrepancy between 2 Chr. 24:20 and Matt. 23:35 are:

- There has been an accidental confusion (or possibly an intentional fusion) of the pre-exilic priest Zechariah son of Jehoiada (2 Chr. 24:20) and the post-exilic prophet Zechariah son of Berechiah (Zech. 1:1).

- The Zechariah son of Berechiah referred to in Innocent Blood is not to be identified with the pre-exilic priest, but with a certain Zechariah son of Baris (ὑιὸν Βάρεις [huion Bareis])

If the first explanation is correct, the fusion or confusion of the two Zechariahs could either be the doing of the author of Matthew (in which case, υἱοῦ Βαραχίου is redactional) or the doing of the anonymous author of the pseudepigraphon in which the words of the Wisdom of God were recorded (in which case, either the First Reconstructor or the author of Luke eliminated υἱοῦ Βαραχίου having recognized the error). On the other hand, if we are correct in determining that in Innocent Blood Jesus quoted from a pre-existing Second Temple-period Jewish pseudepigraphon based on 2 Chr. 24:19-22, then the second explanation can only be correct if the author of Matthew added υἱοῦ Βαραχίου to his source.[123] The second explanation, however, has very little to commend it.[124] The names Berechiah and Baris are not identical,[125] and it is doubtful that the author of Matthew was well acquainted with the events that took place in Jerusalem during the revolt against Rome.[126] Even if he had been aware of the murder of Zechariah son of Baris by the Zealots, it is unlikely that he would have placed a reference to this event on the lips of Jesus, since having Jesus refer to an event that took place after his crucifixion in the past tense would have been an obvious fabrication.

Although there is no a priori reason why the pseudepigraphon Jesus quoted could not have fused or confused the pre-exilic Zechariah son of Jehoiada with the post-exilic Zechariah son of Berechiah,[127] we think it is more likely that υἱοῦ Βαραχίου is a Matthean addition. Luz pointed out that “son of Berechiah,” being in tension with the scriptural account in 2 Chr. 24:19-22, is the more difficult reading and that difficult readings have a strong claim to originality. He therefore argued that the author of Luke omitted υἱοῦ Βαραχίου in order to eliminate the contradiction with the scriptural story.[128] We doubt, however, that the author of Luke was capable of identifying the Zechariah mentioned in Innocent Blood with the individual whose murder is described in 2 Chr. 24:19-22, since according to the LXX version of the story this individual was named Αζαριας τοῦ Ιωδαε (Azarias tou Iōdae, “Azariah the [son] of Iodae”; 2 Chr. 24:20). Therefore, even if the author of Luke had read “Zechariah son of Berechiah” in his source, there is no reason why he should have found this reading to be problematic. On the contrary, as Fitzmyer observed, identifying this unknown (to the author of Luke) Zechariah with the post-exilic Zechariah son of Berechiah would have served the author of Luke’s redactional interests (cf. L14), since this identification would have certified the Zechariah mentioned in Innocent Blood as a prophet.[129]

It would have been just as difficult for the author of Matthew as for the author of Luke to have realized that the Zechariah mentioned in Innocent Blood was the same person as the Azariah mentioned in the LXX version of 2 Chr. 24:19-22. It is not surprising, therefore, that he incorrectly identified the Zechariah mentioned in Innocent Blood with the post-exilic prophet, who was undoubtedly the most famous of the scriptural Zechariahs[130] and in whom the author of Matthew displayed a particular interest.[131] Since “son of Berechiah” is best explained as a Matthean addition, we have omitted υἱοῦ Βαραχίου from GR.[132]

L21 τοῦ ἀπολομένου (GR). In place of Luke’s τοῦ ἀπολομένου (tou apolomenou, “the one destroyed”) Matthew’s version of Innocent Blood reads ὃν ἐφονεύσατε (hon efonevsate, “whom you murdered”). Matthew’s second person accusation is certainly redactional (see above, Comment to L4), and it is likely that the verb with which this accusation is expressed, φονεύειν (fonevein, “to murder”), is redactional, too.[133] It is difficult to see why the First Reconstructor or the author of Luke would have changed φονεύειν to ἀπολλύειν (apollūein, “to destroy”) if the former had occurred in their source, but changing ἀπολλύειν to φονεύειν is an intensification in keeping with the accusatory style the author of Matthew adopted in Innocent Blood.[134] Note, too, that in Calamities in Yerushalayim (L13, L21), which probably stemmed from Anth., the verb ἀπολλύειν was used to compare the impending destruction that threatened Jesus’ audience with the martyrdom of the Galilean pilgrims and the tragedy that befell the victims of the collapse of the tower in Siloam (Luke 13:1-5). Even more telling is the presence of the verb φονεύειν in Matthew’s version of the woe that precedes Innocent Blood (Matt. 23:31). It seems likely that the author of Matthew imported φονεύειν into Innocent Blood from the preceding woe in order to knit the two pericopae more closely together. In view of these facts, we have accepted Luke’s wording in L21 for GR.

הָאוֹבֵד (HR). On reconstructing ἀπολλύειν (apollūein, “to destroy,” “to lose”) with אָבַד (’āvad, “lose,” “destroy”), see Calamities in Yerushalayim, Comment to L13. An example of the participle ἀπολόμενος (apolomenos, “being destroyed”; substantive: “destroyed one”) occurring as the translation of אוֹבֵד (’ōvēd, “lost,” “perishing”) appears in Isaiah:

וּבָאוּ הָאֹבְדִים בְּאֶרֶץ אַשּׁוּר וְהַנִּדָּחִים בְּאֶרֶץ מִצְרָיִם

…and the lost ones [הָאֹבְדִים] in the land of Assyria will come, also the ones scattered in the land of Egypt…. (Isa. 27:13)

καὶ ἥξουσιν οἱ ἀπολόμενοι ἐν τῇ χώρᾳ τῶν Ἀσσυρίων καὶ οἱ ἀπολόμενοι ἐν Αἰγύπτῳ

…and the lost ones [οἱ ἀπολόμενοι] in the land of the Assyrians and the lost ones in Egypt will come…. (Isa. 27:13)

An alternative reconstruction might be הֶהָרוּג (hehārūg, “the one who was killed”), since in Esther we find an example of a participial form of ἀπολλύειν occurring as the translation of הָרוּג:

בָּא מִסְפַּר הַהֲרוּגִים בְּשׁוּשַׁן הַבִּירָה לִפְנֵי הַמֶּלֶךְ

…the number of those killed [הַהֲרוּגִים] in Susa the citadel came before the king. (Esth. 9:11)

ἐπεδόθη ὁ ἀριθμὸς τῷ βασιλεῖ τῶν ἀπολωλότων ἐν Σούσοις

…the number was given to the king of those destroyed [ἀπολωλότων] in Susa. (Esth. 9:11)

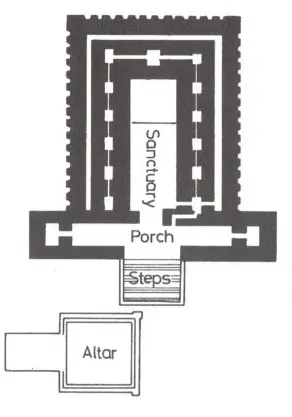

L22-23 μεταξὺ τοῦ θυσιαστηρίου καὶ τοῦ οἴκου (GR). In L22-23 the Lukan and Matthean versions of Innocent Blood are mainly in agreement, the only differences being whether the altar is mentioned in the first place (Luke) or the second (Matt.) and whether the Temple is referred to as the “sanctuary” (Matt.) or the “house” (Luke). There is no discernible reason why the Temple→altar or altar→Temple order was changed and therefore no way to determine which order was original. As to “sanctuary” versus “house,” the former, ναός (naos, “shrine,” “sanctuary”), looks like a Greek stylistic improvement over οἶκος (oikos, “house”), which likely reflects Hebrew usage (see below).[135] If so, Luke’s τοῦ οἴκου (tou oikou, “the house”) probably preserves, via FR, the wording of Anth.[136] Since it was probably the author of Matthew who tinkered with Anth.’s wording by replacing “house” with “sanctuary,” perhaps it is reasonable to suspect that he was also responsible for creating the Lukan-Matthean disagreement regarding the order Temple→altar vs. altar→Temple,[137] but this is merely a guess.

בֵּין הַמִּזְבֵּחַ וּבֵין הַבַּיִת (HR). In LXX the preposition μεταξύ (metaxū, “between”) is exceedingly rare, occurring only once in a book contained in MT (Judg. 5:27). In that sole instance μεταξύ serves as the translation of בֵּין (bēn, “between”). While the repetition of μεταξύ before each location would have been redundant in Greek, Hebrew usually requires בֵּין…וּבֵין (bēn…ūvēn; cf. Gen. 1:4, 14, 18; 3:15), בֵּין…לְבֵין (bēn…levēn; cf. Isa. 59:2) or -בֵּין…וּלְ (bēn…ūle–; cf. Joel 2:17).

In LXX the great majority of instances of θυσιαστήριον (thūsiastērion, “altar”) occur as the translation of מִזְבֵּחַ (mizbēaḥ, “altar”).[138] Likewise, the LXX translators rendered the vast majority of instances of מִזְבֵּחַ as θυσιαστήριον.[139]

Nestle suggested that ναός (“sanctuary”) in Matt. 23:35 and οἶκος (“house”) in Luke 11:51 were translation variants of אוּלָם (’ūlām, “porch”), noting that we find the expression “between the porch and the altar” in Ezek. 8:16 and Joel 2:17.[140] It is far more likely, however, that the disagreements between the Lukan and Matthean parallels are due to redaction at the Greek stage of transmission than reflecting alternate translations of a Hebrew (or Aramaic) tradition or text.[141] Moreover, in addition to instances of “between the porch and the altar,” we also find instances of “from between the altar and the house of the LORD” (2 Kgs. 16:14) or “to the altar and the house” (2 Kgs. 11:11; 2 Chr. 23:10). Since “house” is a Hebraic way of referring to the Temple shrine (cf., e.g., Ezek. 40:47),[142] there is no reason to suppose that anything other than בַּיִת (bayit, “house”) stood behind Luke’s οἶκος.

On reconstructing οἶκος with בַּיִת, see Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, Comment to L33.

Second Chronicles merely states that Zechariah was killed “in the court of the house of the LORD” (2 Chr. 24:21). Why, then, does Innocent Blood specify the location as between the altar and the Temple shrine? Kalimi’s suggestion that the Gospel writers “did not refer to the location of the murder precisely as it appears in Chronicles, since it was not really an important part of [their] core message”[143] is really no solution but merely highlights the problem. If the precise location was not important to them, why bother to be more specific about it than the scriptural text?

Like the Gospels, a rabbinic tradition localizes Zechariah’s murder more specifically than does the story in 2 Chr. 24:19-22:

רבי יודן שאל לרבי אחא איכן הרגו את זכריה בעזרת הנשים או בעזרת ישראל אמר לו לא בעזרת ישראל ולא בעזרת הנשים אלא בעזרת הכהנים

Rabbi Yudan asked Rabbi Aha, “Where did they kill Zechariah? In the Court of Women or the Court of Israel?” He said to him, “Neither in the Court of Israel nor in the Court of Women, but in the Court of the Priests.” (y. Taan. 4:5 [25a])

This rabbinic tradition locates Zechariah’s murder in more or less the same area as the Gospels do in Innocent Blood. The reason for locating Zechariah’s murder in the Court of the Priests in the rabbinic tradition is to increase the culpability of Zechariah’s murderers. Not only did they shed innocent blood, they did so on the most sacred ground of the Temple courts. This same motivation may have been operative in the pseudepigraphon from which Jesus quoted. That the specification of the location of Zechariah’s murder no longer serves a clear purpose in Innocent Blood is a strong argument in support of our conclusion that Jesus did indeed draw the words attributed to the Wisdom of God from a pre-existing source.[144]

L24 ἀμὴν λέγω ὑμῖν (GR). In L24 there is Lukan-Matthean agreement to write λέγω ὑμῖν (legō hūmin, “I say to you”), but the two Gospels disagree about whether this statement should be introduced with ἀμήν (amēn, “Amen!”) or ναί (nai, “yes”). Nevertheless, it is clear that some sort of affirmation introduced λέγω ὑμῖν in Anth. The probability is that Matthew’s highly Hebraic ἀμήν[145] is original,[146] while Luke’s ναί is a concession to Greek style likely introduced by the First Reconstructor.[147]

אָמֵן אֲנִי אוֹמֵר לָכֶם (HR). On reconstructing ἀμήν (amēn, “Amen!”) with אָמֵן (’āmēn, “Amen!”), see Sending the Twelve: Conduct in Town, Comment to L115.

Beginning in L24 Jesus gives his own assessment of the words the Wisdom of God had addressed to the generation of the Babylonian exile.[148] What had been true of that generation would also be true of his.

L25 ἐκζητηθήσεται ἀπὸ (GR). As in L13, Luke’s “it will be sought out from” is to be preferred to Matthew’s “all this will come upon,”[149] since it was Jesus’ intention to simultaneously affirm and reapply Wisdom’s message to his own generation.

יִדָּרֵשׁ מִיַּד (HR). On reconstructing ἐκζητεῖν (ekzētein, “to seek out”) with דָּרַשׁ (dārash, “seek”), see above, Comment to L13.

On reconstructing ἀπό (apo, “from”) with מִיָּד (miyād, “from [the] hand”), see above, Comment to L17.

L26 τῆς γενεᾶς ταύτης (GR). Except for differences in case due to the use of different prepositions in L25, the Lukan and Matthean versions of Innocent Blood are united in their indictment of “this generation.”