How to cite this article: Randall Buth, “‘And’ or ‘But’—So What?,” Jerusalem Perspective 31 (1991): 13-15 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2568/].

מְתֻרְגְּמָן (me⋅tur⋅ge⋅MĀN) is Hebrew for “translator.” The articles in this series illustrate how a knowledge of the Gospels’ Semitic background can provide a deeper understanding of Jesus’ words and influence the translation process. For more articles in this series, click here.

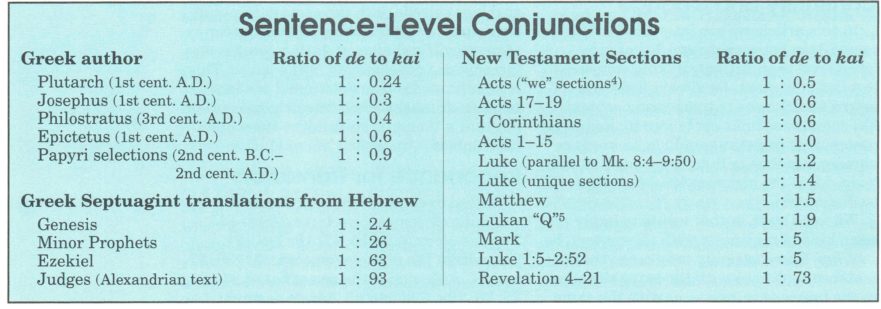

In another article (“Matthew’s Aramaic Glue”) we discussed the importance of words that hold a text together, focusing particularly on the Greek word τότε (tote, “then, at that time”). Here we examine two more linking particles: καί (kai, “and”), and δέ (de, “and; but”). These two Greek words affect translation, they affect our perception of a story, and they have some peculiarities that provide part of the data for understanding the background of the Gospels and the synoptic problem.

Many students ask how a Greek word like de can mean both “and” and “but.” De is also sometimes translated into English by “on the other hand,” “moreover,” “then,” “so,” “however,” or by nothing at all. Actually its true meaning is not expressed by English equivalents. In order to understand de, the student must see how it functions within Greek constructions, and how it differs from kai.

Continuity and Change

In this article we are interested in the comparison between de and kai as sentence-level conjunctions, linking sentences to a larger context. De always links sentences and clauses to their larger context. Kai sometimes links sentences to the larger context, but sometimes only joins words or phrases together or functions as the adverb “even.” It is the sentence-level kais that will be discussed.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium