How to cite this article: David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2020) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/20054/].

Luke 3:10-14[1]

Updated: 18 December 2025

וַיִּשְׁאָלוּהוּ הָאֻכְלוּסִים לֵאמֹר מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה וַיַּעַן וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ שְׁנֵי חֲלוּקוֹת יִתֵּן לְמִי שֶׁאֵין לוֹ וּמִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ מַה יֹּאכַל כָּכָה יַעֲשֶׂה וַיָּבֹאוּ מוֹכְסִים לִטְבּוֹל לְפָנָיו וַיֹּאמְרוּ לוֹ מוֹרֵנוּ מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם אַל תִּפָּרְעוּ מֵאָדָם יוֹתֵר מִמַּה שֶּׁקָּצוּב לָכֶם וַיִּשְׁאָלוּהוּ אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹטִים לֵאמֹר מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם אַל תַּחְמֹסוּ וְאַל תַּעֲשֹׁקוּ אָדָם וְתִתְרַצּוּ בְּאָפְסַנְיוֹתְכֶם

The people in the crowd asked Yohanan, “What should we do to bring our repentance to fruition?”

“Whoever owns two sets of clothing should share with those who have nothing to wear,” he replied. “And whoever has food to eat should share with those who are going hungry.”

Some toll collectors also came to Yohanan to be purified under his supervision, and they asked, “Teacher, what should we do to bring our repentance to fruition?”

“Don’t take more toll money from anyone than what the authorities have assigned to you,” he replied.

Some soldiers asked Yohanan, “What should we do to bring our repentance to fruition?”

“Don’t extort or oppress anyone,” he replied. “Rather, be satisfied with your keep.”[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations, click on the link below:

Story Placement

Between Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance and Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse, the author of Luke included a pericope in which the people in John’s audience are given a voice. In response to the Baptist’s demand to make fruit worthy of repentance, the members of his audience ask, “What [fruit of repentance] might we make?”[3] This question, repeated by different segments of John’s audience, is a logical response to the Baptist’s message, and therefore does not appear to be an intrusion from a separate source into Luke’s account of John the Baptist. The ease with which Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations reverts to Hebrew likewise argues against attributing this pericope to Lukan authorship or to any source other than the Anthology (Anth.), the source from which the other pericopae on John the Baptist in Luke 3 are derived.

The question remains, however, why the author of Matthew would have omitted Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations if it appeared in Anth., as we suppose. We believe the answer lies in the editorial changes the author of Matthew made to the opening of Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance, where he changed the identity of John’s audience from the diverse crowds (as in Luke 3:7) to the Pharisees and Sadducees (Matt. 3:7).[4] This change of the audience’s composition excluded the presence of toll collectors and soldiers, and, given the author of Matthew’s entirely negative attitude toward the Pharisees and Sadducees, the author of Matthew had no motive for placing the question “What fruit of repentance should we make?” on the lips of these two Jewish groups. In Matthew’s Gospel John the Baptist’s audience is portrayed in an entirely negative light and John’s message to them is solely one of condemnation. In order to include Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations the author of Matthew would have needed to introduce new members of the cast, as it were, and to portray the Baptist in a less uncompromising light, neither of which served his purpose of condemning from the very outset of his Gospel the Pharisees and Sadducees. Thus, excluding Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations served the author of Matthew’s literary and theological agendas.[5]

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

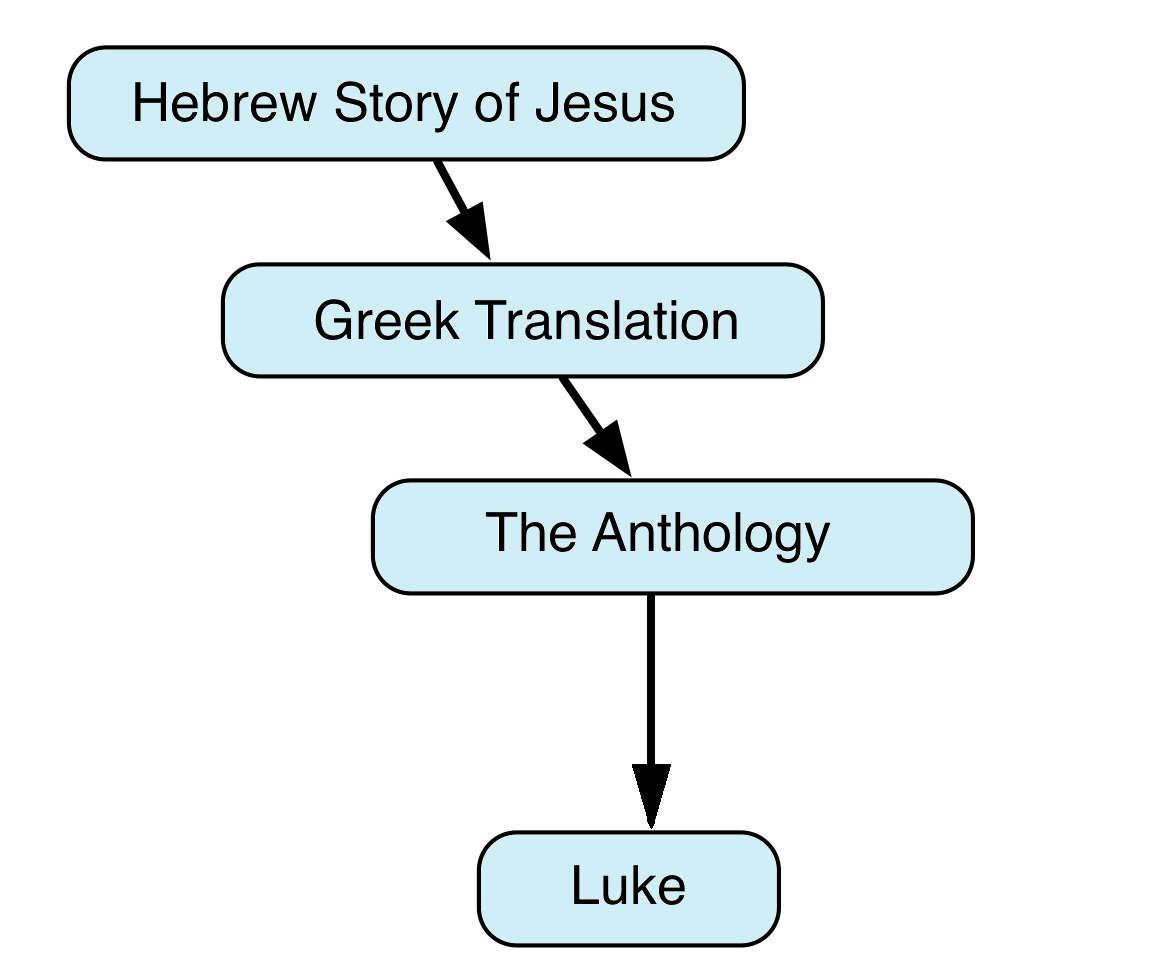

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

As we noted above, the relative ease with which Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations reverts to Hebrew suggests that the author of Luke copied this pericope from his Hebraic-Greek source, the Anthology (Anth.), the source he shared with the author of Matthew.[6] This conclusion is also supported by the author of Luke’s habit of copying large blocks of Anth. material without insertions from his second source, the First Reconstruction (FR).[7]

As we noted above, the relative ease with which Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations reverts to Hebrew suggests that the author of Luke copied this pericope from his Hebraic-Greek source, the Anthology (Anth.), the source he shared with the author of Matthew.[6] This conclusion is also supported by the author of Luke’s habit of copying large blocks of Anth. material without insertions from his second source, the First Reconstruction (FR).[7]

Scholars who deny that Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations belonged to the source common to the authors of Luke and Matthew, usually referred to as “Q,” often do so on the grounds that the pericope is absent in Matthew and that the portrayal of John the Baptist in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations is different from how the Baptist is portrayed in the pericopae definitely ascribed to Q.[8] But as we noted above in the Story Placement discussion, the author of Matthew had strong literary and theological motives for omitting this pericope, an observation that tends to neutralize the first grounds for denying the ascription of Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations to the shared Lukan and Matthean source. The dissimilarity of the portrayal of John the Baptist in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations from his portrayal in undisputed Q pericopae amounts to the Baptist’s practical instruction in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations versus his eschatological orientation in Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance and Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse. However, since John the Baptist’s eschatological warnings were motivated by a desire to induce practical changes of behavior in the present (i.e., repentance), the contrast between the portrayal of John in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations and other pericopae should not be overemphasized.

Indeed, there appears to be a thematic continuity uniting Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance and Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations of which the author of Luke was unaware, namely John the Baptist’s Essene-like suspicion of the dangers of wealth. In Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance we noted that John’s message seems to have been indebted to Zephaniah’s prophetic words about the coming of the LORD’s wrath (Zeph. 1:18-2:3), a warning that opens with the words “Neither their silver nor their gold will be able to deliver them on the day of the LORD’s wrath” (Zeph. 1:18). If this prophetic warning stood in the background of John’s message, it might help explain why each of his exhortations to the various groups that questioned him deals in some way with the correct handling of possessions and property. Since possessing wealth would be of no avail in stemming the tide of God’s wrath, John recommended the people use their property in ways that would actualize their repentance.[9]

Not only does the content of John’s teaching in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations indicate literary continuity, but hortatory instruction and eschatological prediction should be regarded as complimentary rather than as mutually exclusive.[10] The eschatological orientation of the Essenes did not prevent them from detailed elaboration of the proper performance of the commandments in their writings. On the contrary, they regarded their study of Torah as their way of fulfilling the prophetic call to “prepare the way of the LORD” (Isa. 40:3; 1QS VIII, 12-16). It should not be surprising, therefore, to find John the Baptist engaging in practical instruction in his role as the Voice summoning his generation to prepare the LORD’s way.[11] Moreover, Josephus, the only ancient writer outside the New Testament to bear witness to John the Baptist, described him as a teacher of morals (Ant. 18:117).[12] While Josephus’ suppression of John’s eschatological message was certainly tendentious, his portrayal of the Baptist as giving his audience practical instruction was probably not fabricated. The author of Luke appears to be the only ancient historian to have captured both sides of the Baptist’s character, making his portrait of John the Baptist the most valuable and accurate we possess.

Another challenge some scholars have mounted against the ascription of Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations to the source shared by the authors of Luke and Matthew is the suggestion that the author of Luke composed Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations as a way of clearing John the Baptist of suspicion of anti-Roman sentiments and intentions.[13] According to this view, the author of Luke wrote Luke 3:10-14 in order to present John the Baptist as accepting the legitimacy of Roman imperial rule by portraying John as willing to accept its local representatives—toll collectors and soldiers—as candidates for baptism. The weakness of this argument is that if it had been the author of Luke’s intention to portray John the Baptist as pro-Roman, he did so in an extremely clumsy and ineffectual manner.

The assumption behind John’s instructions to the toll collectors and soldiers is that, left to their own devices, they will abuse their positions of authority in order to exploit and harass the subjugated population. Rather than succeeding in portraying John the Baptist as pro-Roman, Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations conveys a highly subversive message about the workings of the Roman imperialist government. It is unlikely that the Roman government, which did not regard freedom of speech as an inalienable human right, would have listened to John’s message—coming from the mouth of a non-citizen in a distant and insignificant tetrarchy—with a sympathetic ear. If this was the best the author of Luke could offer up to prove that John the Baptist was pro-Roman, he would have done better to remain silent.

We, on the other hand, do not regard the author of Luke as a well-intentioned but hapless defender of John the Baptist. Luke’s portrayal of John as willing to bear with the status quo resembles an Essene-style resolve to act toward the governing authorities “like a slave to the one ruling him and like someone oppressed before one domineering him” (1QS IX, 22-23).[14] For John the Baptist, as for the Essenes, active transformation of the social order was not on his agenda. That transformation God would accomplish when the times had reached their fulfillment.

Crucial Issues

- Should the soldiers who came to John the Baptist be identified as Jews or Gentiles?

- What inferences should be drawn from the fact that John did not require the soldiers to forsake their military service?

Comment

L1 καὶ ἐπηρώτησαν αὐτὸν οἱ ὄχλοι λέγοντες (GR). Apart from his use of an imperfect verb, Luke’s wording in L1 is highly Hebraic, reverting word-for-word to Hebrew. Since the author of Luke probably was responsible for the imperfect ἔλεγεν (elegen, “he was saying”) in Luke 3:7 (see Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance, Comment to L4), it is likely that he also was responsible for the imperfect ἐπηρώτων (epērōtōn, “they were asking”) here in Luke 3:10.[15] For GR we have replaced the imperfect verb with the aorist ἐπηρώτησαν (epērōtēsan, “they asked”).

וַיִּשְׁאָלוּהוּ הָאֻכְלוּסִים לֵאמֹר (HR). On reconstructing ἐπερωτᾶν (eperōtan, “to ask”) with שָׁאַל (shā’al, “ask”), see Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L5-6. On reconstructing ὄχλος (ochlos, “crowd”) with אֻכְלוּס (’uchlūs, “crowd”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L4.

We have reconstructed L1 using the BH-style infinitive לֵאמֹר (lē’mor, “to say”) rather than the MH-style לוֹמַר (lōmar, “to say”). This decision, together with our use of vav-consecutive (וַיִּשְׁאָלוּהוּ), reflects our preference for reconstructing narrative in a biblicizing style of Hebrew. Biblicizing style combined with post-biblical Hebrew words, such as אֻכְלוּס, is typical of late Second Temple literary works, such as the fragment of an historical account preserved in b. Kid. 66a.

The crowds, who were introduced as early as A Voice Crying (L53), and who were indirectly referenced in Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance (L1), are finally given the opportunity to speak for themselves.

L2 τί ποιήσωμεν (GR). Just as we suspect that the author of Luke inserted the conjunction οὖν (oun, “therefore”) in Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance (L4), so we believe he may have added it to the wording of his source here in L2.[16] Including οὖν makes for stylistically better Greek, and it was probably added for that reason, so we have accordingly omitted οὖν from GR. On the other hand, the two Lukan-Matthean agreements to write οὖν in Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance (L10 and L19), which indicate the presence of this conjunction in Anth., caution us against being dogmatic with respect to this conclusion.

Pomegranate fruit. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In Codex Bezae the laconic question τί ποιήσωμεν (ti poiēsōmen, “What might we do/make?”; Luke 3:10, 12, 14) is completed by the additional words ἵνα σωθῶμεν (hina sōthōmen, “in order that we might be saved”). Since a similar question is posed in Acts 16:30 (τί με δεῖ ποιεῖν ἵνα σωθῶ [“What is required of me to do in order that I might be saved?”]), and since in Luke’s version of the Four Soils interpretation we read that the word of God is taken from the hearts of certain hearers ἵνα μὴ…σωθῶσιν (“in order that they might not be saved”; Luke 8:12),[17] we might suppose that ἵνα σωθῶμεν in Luke 3:10, 12, 14 is original. But against this conclusion is the unlikelihood that scribes would have dropped ἵνα σωθῶμεν from these verses had they been aware of this reading.

The scribe who produced Codex Bezae, being familiar with these instances of ἵνα σωθῶμεν in the writings of Luke, may have assumed that ἵνα σωθῶμεν correctly completed the questions addressed to John the Baptist. Rice, on the other hand, suggested that the Bezae scribe added ἵνα σωθῶμεν under the influence of Luke’s quotation of Isa. 40:5, which implies that because of John the Baptist’s ministry “all flesh will see the salvation of God” (LXX). By adding ἵνα σωθῶμεν to the questions addressed to John, the Bezae scribe made the Baptist’s fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy explicit.[18]

In any case, it is highly unlikely that ἵνα σωθῶμεν was part of the question put to John the Baptist in Anth., not only because ἵνα + subjunctive clauses are un-Hebraic and therefore unlikely to reflect the Greek translation of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua,[19] but also because the addition of “in order to be saved” to the question obscures the original connection between the question and the Baptist’s demand to produce the fruit of repentance.[20] A more correct expansion of the laconic question would have been τί καρπὸν ποιήσωμεν (ti karpon poiēsōmen, “What fruit might we make?”).

מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה (HR). On reconstructing ποιεῖν (poiein, “to do”) with עָשָׂה (‘āsāh, “do”), see Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L8. In LXX we often find variations of questions formulated with τί + ποιεῖν as the translation of עָשָׂה + מַה.[21] In Judg. 13:8 τί ποιήσωμεν (ti poiēsōmen, “What might we do?”), the exact wording in GR, occurs as the translation of מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה (mah na‘aseh, “What will we do?”), the wording we have adopted for HR.[22]

L3 ἀποκριθεὶς δὲ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς (GR). The only change the author of Luke likely made to Anth.’s wording in L3 was to use the imperfect ἔλεγεν (elegen, “he was saying”) in place of the aorist εἶπεν (eipen, “he said”).[23] See our discussion of a similar exchange of a perfect verb with an imperfect verb in Comment to L1.

וַיַּעַן וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם (HR). On reconstructing ἀποκρίνειν (apokrinein, “to answer”) with עָנָה (‘ānāh, “answer”), see Call of Levi, Comment to L56.

L4 מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ שְׁנֵי חֲלוּקוֹת (HR). On reconstructing ὁ ἔχων (ho echōn, “the one having”) with מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ (mi sheyēsh lō, “who that there is to him”), see Four Soils parable, Comment to L61.

On reconstrcting δύο (duo, “two”) with שְׁנַיִם / שְׁתַּיִם (shenayim [masc.] / shetayim [fem.], “two”), see Sending the Twelve: Commissioning, Comment to L30.

On reconstructing χιτών (chitōn, “tunic”) with חָלוּק (ḥālūq, “tunic”), see Sending the Twelve: Conduct on the Road, Comment to L74.

Sculpture of a man wearing the garment known as the χιτών (chitōn). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The garment to which John the Baptist referred was the one worn next to the skin, usually made of linen.[24] Since men and women both wore the same type of clothing,[25] the Baptist’s admonition would have applied equally to all members of his audience.

According to Hippolytus of Rome (ca. 170-236 C.E.), the Essenes did not own two tunics (χιτῶνας…δύο…οὐ κτῶνται; Refutation of All Heresies, 9:20),[26] their limited wardrobe being an expression of their commitment to voluntary poverty. The source of Hippolytus’ information is not known; it is not found in Josephus’ discussion of the Essenes, to which Hippolytus’ account bears strong resemblance. Some scholars have suggested that Hippolytus did not rely on Josephus’ account, but on the same first-century source Josephus himself had used.[27] Since there is no reason for Hippolytus to have made up this detail about the Essenes’ practices,[28] and given the possibility that it comes from an early source, the report that the Essenes did not own two sets of clothing appears credible.[29] John’s insistence that the same standards regarding personal property should be observed by those coming to his baptism suggests that the Baptist envisioned a radical democratization of the Essene concept of the community of goods.[30] In place of the Essenes’ closed system of collective ownership, intended to keep the Essenes separate from the morally impure society at large, John expected all his fellow Israelites to share all their belongings with those in need.

L5 δότω τῷ μὴ ἔχοντι (GR). We suspect that the compound verb μεταδιδόναι (metadidonai, “to distribute,” “to share”) in L5 may be the product of Lukan redaction. Compound verbs are often indicative of Greek stylistic polishing and, accordingly, μεταδιδόναι is rare in LXX, occurring only once as the translation of a Hebrew term.[31] We think it is likely, therefore, that Anth. had the imperative δότω (dotō, “Give!”) from the simple verb διδόναι (didonai, “to give”). Otherwise, the author of Luke appears to have accepted the wording of Anth. in L5.

יִתֵּן לְמִי שֶׁאֵין לוֹ (HR). On reconstructing διδόναι with נָתַן (nātan, “give”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L18. John’s answer is laconic. He neither specified what the one owning two tunics ought to give, nor what the one who does not have lacks. Did John mean that a person who is wealthy enough to own two tunics should merely give alms to those who are not fortunate enough to own two sets of clothing? Or did he intend “the one who does not have” to be understood in an absolute sense, namely there is only an obligation to give to a person who is completely without possessions of any kind? Such narrow readings of John’s exhortation render it almost completely null, since one would be hard pressed to find a human being who is absolutely without any possession whatsoever, and allowing his hearers to purchase repentance for a nominal sum hardly seems consistent with the Baptist’s severe demeanor. While we considered reconstructions such as יִתֵּן אֶחָד לְמִי שֶׁאֵין לוֹ חָלוּק (“Let him give one [tunic] to one who has no tunic”), which would make John’s intention explicit, this is not supported by the Greek text and the context makes John’s meaning plain. We have therefore declined to make HR more explicit than GR.

First-century C.E. still-life fresco from Pompeii. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

L6 וּמִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ מַה יֹּאכַל כָּכָה יַעֲשֶׂה (HR). On reconstructing ὁ ἔχων (ho echōn, “the one having”) with מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ (mi sheyēsh lō, “who that there is to him”), see above, Comment to L4. How the plural noun βρώματα (brōmata, “foodstuffs”) ought to be reconstructed is uncertain. In LXX βρῶμα (brōma, “food”) usually occurs as the translation of אֹכֶל (’ochel, “food”) or, less often, מַאֲכַל (ma’achal, “food”).[32] These are certainly viable options for HR, but they do not explain the plural form of the Greek noun. Searching in Hebrew sources for ways of expressing “one who has food,” we noted the phrases מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ מַה יֹּאכַל (mi sheyēsh lō mah yo’chal, “one who has something to eat”) and מִי שֶׁאֵין לוֹ מַה יֹּאכַל (mi she’ēn lō mah yo’chal, “one who has nothing to eat”), which occur several times in rabbinic texts. An example is found in the following rabbinic statement:

מי שיש לו מה יאכל היום ואומר מה אני אוכל למחר הרי זה מחוסר אמנה

Whoever has something that he can eat [מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ מַה יֹּאכַל] today but says, “What will I eat tomorrow?”: behold, this is one who lacks faith. (Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Vayassa‘ chpt. 3 [ed. Lauterbach, 1:234-235])[33]

Perhaps the indeterminate phrase מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ לוֹ מַה יֹּאכַל prompted the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua to use the plural noun βρώματα (brōmata, “foodstuffs”) while rendering Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations into Greek.

In LXX the adverb ὁμοίως (homoiōs, “likewise”) is rather uncommon and rarely has a Hebrew equivalent. Where there is a Hebrew equivalent, ὁμοίως occurs twice as the translation of -כְּ (ke–, “as,” “like”; Prov. 1:27; 4:18).[34] Perhaps in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations ὁμοίως was used to translate the adverb כָּכָה (kāchā, “thus,” “in this manner”). The following examples of כָּכָה are similar to our reconstruction:

כָּכָה תַּעֲשֶׂה לַלְוִיִּם בְּמִשְׁמְרֹתָם

Thus [כָּכָה] you will do to the Levites in their divisions. (Num. 8:26)

וְאִם־כָּכָה אַתְּ עֹשֶׂה לִּי הָרְגֵנִי נָא הָרֹג אִם־מָצָאתִי חֵן בְּעֵינֶיךָ

If thus [כָּכָה] you do to me, then kill me outright, if I have found favor in your eyes. (Num. 11:15)

כָּכָה יֵעָשֶׂה לַשּׁוֹר הָאֶחָד אוֹ לָאַיִל הָאֶחָד

In this manner [כָּכָה] it will be done with each bull or with each ram…. (Num. 15:11)

כָּכָה יֵעָשֶׂה לָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר לֹא־יִבְנֶה אֶת־בֵּית אָחִיו

In this manner [כָּכָה] it will be done to the man who will not build his brother’s house! (Deut. 25:9)

חִזְקוּ וְאִמְצוּ כִּי כָכָה יַעֲשֶׂה יי לְכָל־אֹיְבֵיכֶם אֲשֶׁר אַתֶּם נִלְחָמִים אוֹתָם

Be strong and courageous, for thus [כָכָה] the LORD will do to all your enemies against whom you wage battle. (Josh. 10:25)

ככה יעשו שנה בשנה כול יומי ממשלת בליעל

Thus [כָּכָה] they will do year by year all the days of the dominion of Belial. (1QS II, 19)

Another option for reconstructing ὁμοίως is כֵּן (kēn, “thus,” “in this manner”). The following examples of the adverb כֵּן are similar to our reconstruction:

כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה אֹתוֹ אֱלֹהִים כֵּן עָשָׂה

According to all that God commanded him, thus [כֵּן] he did. (Gen. 6:22)

וַיֹּאמְרוּ כֵּן תַּעֲשֶׂה כַּאֲשֶׁר דִּבַּרְתָּ

And they said, “Thus [כֵּן] you should do, even as you have spoken.” (Gen. 18:5)

כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יי אֶת־מֹשֶׁה וְאַהֲרֹן כֵּן עָשׂוּ

Even as the LORD commanded Moses and Aaron, thus [כֵּן] they did. (Exod. 12:28)

כַּאֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה כֵּן יֵעָשֶׂה לּוֹ

…even as he did, thus [כֵּן] it will be done to him. (Lev. 24:19)

כַּאֲשֶׁר דִּבֶּר יי אֶל־מֹשֶׁה כֵּן עָשׂוּ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל

Even as the LORD had spoken to Moses, thus [כֵּן] the children of Israel did. (Num. 5:4)

כְּפִי נִדְרוֹ אֲשֶׁר יִדֹּר כֵּן יַעֲשֶׂה

…according to his vow that he vowed, thus [כֵּן] he must do…. (Num. 6:21)

כַּאֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יי אֶת־מֹשֶׁה עַבְדּוֹ כֵּן־צִוָּה מֹשֶׁה אֶת־יְהוֹשֻׁעַ וְכֵן עָשָׂה יְהוֹשֻׁעַ

As the LORD commanded Moses his servant, thus [כֵּן] Moses commanded Joshua, and thus [וְכֵן] Joshua did. (Josh. 11:15)

John’s instruction regarding the sharing of food is even more laconic than his instruction about clothing, but as in the former case, his intention is clear: those who have food for the present, even if it is only a little, ought to share with those who have nothing to eat. This exhortation was as applicable to the relatively impoverished as it was to the excessively wealthy. John’s instructions about food and clothing prefigure Jesus’ attempts in Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry to allay the fears of his disciples—who had given up their possessions and livelihoods in order to follow Jesus—about food and drink and clothing. We may suppose, therefore, that Jesus and his full-time disciples are examples of first-century Jews who had followed John’s instructions as he had intended them to be carried out.

L7 ἦλθον δὲ τελῶναι βαπτισθῆναι (GR). We have accepted all of Luke’s wording for GR with the exception of the καί (kai, “and”) which follows the δέ (de, “but”) in Luke 3:12, since the addition of καί after δέ is characteristic of Lukan redaction.[35]

וַיָּבֹאוּ מוֹכְסִים לִטְבּוֹל לְפָנָיו (HR). On reconstructing ἔρχεσθαι (erchesthai, “to come”) with בָּא (bā’, “come”), see Demands of Discipleship, Comment to L8. On reconstructing τελώνης (telōnēs, “toll collector”) with מוֹכֵס (mōchēs, “toll collector”), see Call of Levi, Comment to L10.

Saint John the Baptist and the Pharisees (Saint Jean-Baptiste et les pharisiens) by the artist James Tissot. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The toll collectors who came to John the Baptist were almost certainly Jews, like the disciple Levi, who collected tolls on imported goods that passed through the territory governed by Herod Antipas. On toll collecting in the Gospels, see Call of Levi, Comment to L10.

On reconstructing the passive infinitive βαπτισθῆναι (baptisthēnai, “to be immersed”) with לִטְבּוֹל לְפָנָיו (litbōl lefānāv, “to immerse in his presence”), see A Voice Crying, Comment to L57.

L8 καὶ εἶπον πρὸς αὐτόν (GR). We have accepted all of Luke’s wording in L8 for GR. In critical editions we find the spelling εἶπαν (eipan, “they said”) in place of εἶπον (eipon, “they said”), which is the reading of Codex Vaticanus. There is no difference in meaning between the two forms of the verb.

L9 διδάσκαλε τί ποιήσωμεν (GR). Why are the toll collectors the only group to address John the Baptist as “teacher”? Did the author of Luke add this title of address to his source? If so, why did he not add it in L2 and L14? Did the author of Luke remove it from the first and last question? If so, why did he retain it in L9? Since there are no satisfactory answers to these questions, we are left to conclude that the author of Luke included the respectful address in L9, but not in the other cases, because this is how the questions appeared in Anth. Why only the toll collectors addressed John the Baptist in this way remains mysterious.

מוֹרֵנוּ מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה (HR). Elsewhere we have reconstructed διδάσκαλος (didaskalos, “teacher”) with רַב (rav, “master”),[36] and this remains a viable option for HR in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations. Given the Baptist’s similarity to the Essenes, however, we have preferred מוֹרֶה (mōreh, “teacher,” “instructor”) for HR, which is also a more literal equivalent of διδάσκαλος. According to DSS, the Essenes referred to the founder of their sect as מוֹרֶה הַצֶּדֶק (mōreh hatzedeq, “the teacher of righteousness”; cf., e.g., 1QpHab I, 13; II, 2; V, 10), and it seems reasonable to suppose that other leaders within the Essene community and leaders of movements distinct from, but close to, the Essenes would also have borne the title מוֹרֶה.

On reconstructing τί ποιήσωμεν (ti poiēsōmen, “What might we do?”) with מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה (mah na‘aseh, “What will we do?”), see above, Comment to L2.

L11 μηδὲν πλέον παρὰ τὸ διατεταγμένον ὑμῖν πράσσετε (GR). Although placing the imperative πράσσετε (prassete, “Extract money!”) after μηδέν (mēden, “nothing”) would make for a more Hebraic word order, for GR we have accepted Luke’s wording as it is. The Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua did not always reproduce the exact word order of his source.

Bas-relief on a third-century C.E. tombstone of a Pannonian merchant or tax collector. The deceased is shown sitting at a table, ledger in hand, counting his coins while his clerk reads accounts from a scroll. Image courtesy of the National Museum of Serbia.

אַל תִּפָּרְעוּ מֵאָדָם יוֹתֵר מִמַּה שֶּׁקָּצוּב לָכֶם (HR). The verb πράσσειν (prassein, “to do,” “to exact payment”) is relatively uncommon in LXX, but where it does occur it usually does so as the translation of עָשָׂה (‘āsāh, “make,” “do”) or פָּעַל (pā‘al, “act,” “do”).[37] Since neither of these verbs suits the context of Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations, we must seek an alternative reconstruction.

The semantic range of πράσσειν includes not only “to exact payment,” but also “to punish.”[38] This same semantic range is covered by the MH verb נִפְרַע (nifra‘) when accompanied by the preposition מִן (min, “from”). The following statement from the Babylonian Talmud supplies an example:

אין הקב″ה נפרע מן האדם עד שתתמלא סאתו

The Holy One, blessed is he, does not punish [lit., “exact payment from”] a person until his measure is filled up. (b. Sot. 9a)

A statement in the Mishnah uses the extraction of payment expressed with נִפְרַע מִן as a metaphor for divine reckoning:

וְהַגַּבָּאִים מְחַזְּ

ירִים תָּמִיד בְּכָל יוֹם וְנִפְרָעִין [מִן] הָאָדָם לְדַעְתּוֹ וְשֶׁלֹּא לְדַעְתּוֹ…but the collectors always come around every day and exact payment from a person with his consent or without his consent…. (m. Avot 3:16)

The imagery in the rabbinic metaphor is similar to the real-life scenario envisioned in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations. This is especially the case since the noun גַּבַּיי (gabai, “collector”) was used to refer to collectors of the poll tax, and as such was sometimes coupled with מוֹכֵס (mōchēs, “toll collector”) in reference to persons suspected of unfairly extracting more payment from unwary or defenseless victims than was their due (cf. t. Bab. Metz. 8:26). Indeed, these two classes of professionals are singled out in the aforementioned Tosefta passage as examples of persons for whom repentance is difficult because of the challenge of making restitution to everyone they had cheated.[39] Their similar semantic ranges and their use in similar contexts commend נִפְרַע מִן as a solid option for reconstructing πράσσειν in L11.

The construction -יוֹתֵר מִמַּה שֶּׁ (yōtēr mimah she-, “more than what is…”), which we have used to reconstruct πλέον παρὰ τὸ διατεταγμένον (pleon para to diatetagmenon, “more than the assigned”), is attested in rabbinic sources. An example is found in the description of the high priests’ public reading of Scripture in the Temple:

וְגוֹלֵל אֶת הַתּוֹרָה וּמַנִּיחָהּ בְּחֵיקוֹ וְאוֹמֵ′ יֹתֶר מִמָּה שֶׁקָּרִיתִי לִפְנֵיכֵם כָּתוּב

…and [having finished] he rolls up the Torah [scroll] and places it in his bosom and says, “More than what [-יֹתֶר מִמָּה שֶׁ] I have read before you is written.” (m. Sot. 7:7; cf. m. Yom. 7:1)[40]

We owe our reconstruction of τὸ διατεταγμένον ὑμῖν (to diatetagmenon hūmin, “the [amount] assigned to you”) as קָצוּב לָכֶם (qātzūv lāchem, “assigned to you”) to Gill’s observation that the Babylonian Talmud refers to a toll collector who has no assigned limit (מוֹכֵס שֶׁאֵין לוֹ קִצְבָה; b. Ned. 28a).[41] The Talmud’s reference to a toll collector who has no limit comes in response to the Mishnah’s ruling that it is permissible to lie to toll collectors in order to evade payment (m. Ned. 3:4).[42] This was the opinion of Bet Hillel, and likely comes from the period before the destruction of the Temple when the schools of Hillel and Shammai were still divided. The perspective expressed in the Mishnah is one that resents Roman imperialism and the government of its puppet rulers, the Herodians. The view expressed in the Talmud, on the other hand, is a diaspora perspective, which assumes it is natural to be ruled by foreign rulers in a foreign land. Under diaspora conditions the guiding principle was “the law of the land is the law,” and therefore the Mishnah’s permissiveness toward evading tolls is regarded in the Talmud as setting a dangerously destabilizing precedent. In order to limit the scope of the Mishnah’s ruling, a Babylonian sage suggests that lying in order to evade tolls is only allowed when the government has put no restrictions on the amount the toll collector is permitted to collect, in other words, when the toll collector has no קִצְבָה (qitzvāh, “limit”). The cognate verb קָצַב (qātzav) can mean “define an amount,” “determine” or “limit,” and as such makes for a suitable reconstruction of διατάσσειν (diatassein, “to appoint,” “to assign”)—τὸ διατεταγμένον being a substantive passive participle of this verb—in Luke 3:13.

We find an example of -קָצוּב לְ (qātzūv le–, “assigned to [someone/something]”), parallel to our reconstruction, in the following statement:

כל מזונותיו של אדם קצובים לו מראש השנה ועד יום הכפורים

The whole of a person’s [annual] provision of food is assigned to him [קְצוּבִים לוֹ] [during the period] from Rosh HaShanah to Yom Kippur. (b. Betz. 16a)

L12 ἐπηρώτησαν δὲ αὐτὸν (GR). As in L1, we believe that the imperfect ἐπηρώτων (“they were asking”) is likely secondary.[23] Whether the change was made by the author of Luke or by a later scribe—a possibility given Bezae’s ἐπηρώτησαν (“they asked”) in Luke 3:14—it is probable that the aorist ἐπηρώτησαν was the reading of Anth.

וַיִּשְׁאָלוּהוּ (HR). On reconstructing ἐπερωτᾶν (eperōtan, “to ask”) with שָׁאַל (shā’al, “ask”), see above, Comment to L1.

L13 στρατευόμενοι λέγοντες (GR). From GR we have omitted the conjunction καί (kai, “and”), which looks like another example of the author of Luke’s editorial δὲ καί construction (see above, Comment to L7). Otherwise, the author of Luke appears to have faithfully transmitted Anth.’s wording in L13. Note that whereas the term for “soldier” in Luke 3:14 is the substantive participle στρατευόμενος (stratevomenos, “one serving as a soldier”), a term that does not reoccur in Luke or Acts, elsewhere in his writings the author of Luke preferred to use the nouns στρατιώτης (stratiōtēs, “soldier”; Luke 7:8; 23:36; Acts 10:7; 12:4, 6, 18; 21:32 (2xx), 35; 23:23, 31; 27:31, 32, 42; 28:16) or στράτευμα (stratevma, “soldier”; Luke 23:11; Acts 23:10, 27) to refer to soldiers. Thus the use of στρατευόμενος in Luke 3:14 cannot be attributed to Lukan style, but probably reflects the wording of his source (Anth.).

אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹטִים לֵאמֹר (HR). Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew are surprisingly wanting in terms for “soldier.” Perhaps this is a reflection of Israel’s historical experience, since there does not appear to have been a standing Israelite army during the period of the monarchy, and throughout most of the Second Temple period Israel was ruled by Gentile kingdoms. The most common word for “soldier” that we encounter in rabbinic sources, אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹט (’isṭeraṭyōṭ, “soldier”), is a loanword based on the Greek term στρατιώτης (stratiōtēs, “soldier”).[43] Examples of אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹט include:

מעשה ששילח המלכות שני איסטרטיוטות ללמוד תורה מרבן גמליאל

It happened that the [Roman] empire sent two soldiers [אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹטוֹת] to study Torah from Rabban Gamliel…. (y. Bab. Kam. 4:3 [19b])

שני תלמידים משלר′ יהושע שינו עטיפתם בשעת השמד פגע בהם איסטרטיוט אחד משומד אמר להם אם בניה אתם תנו נפשכם עליה ואם אין אתם בניה למה אתם נהרגין עליה

Two disciples from those of Rabbi Yehoshua changed their cloaks during the time of persecution. A certain soldier [אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹט], an apostate, met them. He said to them, “If you are her sons [i.e., the Torah’s], give your life for her. But if you are not her sons, why be killed for her?” (Gen. Rab. 82:8 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 2:984-985])

למלך שנכנס למדינה ועמו דוכסין ואיפרכין ואיסטראטיאוטין

[It may be compared] to a king who entered a province and with him were generals and governors and soldiers [אִיסְטְרַאטִיאוֹטִין]…. (Lev. Rab. 18:1 [ed. Margulies, 1:396])

מעשה בשני בניו של [ר′] צדוק הכהן הגדול שנשבו אחד זכר ואחת נקבה, נפל זה לאחד איסטרטיוט, [וזו לאחד איסטרטיוט]

An anecdote concerning two children of [Rabbi] Zaddok the high priest who were captured, one a boy and the other a girl. The boy fell to [the lot of] a certain soldier [אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹט] [and the girl to that of a certain other soldier (אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹט)]. (Lam. Rab. 1:16 §46 [ed. Buber, 42a])[44]

Who were the soldiers that came to John the Baptist? Although it occasionally has been suggested that they were Gentiles,[45] this seems highly improbable[46] in light of the instruction John gave them. Had the soldiers who approached John been Gentiles, it would have made better sense for John to have exhorted them to stop worshipping idols and turn to the God of Israel than for him to advise them not to take advantage of civilians by abusing their authority. Moreover, John’s warning to the crowds, which included the soldiers, that appealing to their Abrahamic descent would be useless (Matt. 3:9; Luke 3:8), presupposes that the makeup of John’s audience was entirely Jewish.[47]

Two soldiers depicted in a fresco from the Dura Europos synagogue. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Some scholars have suggested that by “soldiers” Luke intended a Jewish police force who supported the work of Jewish toll collectors,[48] but they do not cite sources proving that such police backup actually existed. We do, however, hear of Jewish soldiers who were in the service of the Herodian rulers.[49] According to Josephus, Herod the Great established a Jewish military colony called Bathyra on the frontier with Trachonitis (Ant. 17:23-31). Jewish soldiers from this colony remained in the service of Philip the tetrarch (Ant. 17:27), a contemporary of John the Baptist, and in the service of Agrippa II (Ant. 17:31), who was in power around the time of the Jewish revolt against Rome, which broke out in 66 C.E. Since Jewish soldiers from Bathyra were active in the time of John the Baptist, and since Bathyra on the Trachonite frontier was not too distant from the Galilee, where we presume John’s activities were focused, it is possible that the soldiers who came out to John were from this very military colony.[50] It is also possible that the Jewish soldiers mentioned in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations were in the service of Herod Antipas.[51]

L14 τί ποιήσωμεν (GR). From GR we have omitted καὶ ἡμεῖς (kai hēmeis, “and we”), which we suspect was added by the author of Luke as a stylistic improvement that signaled the culmination of the question-and-answer exchange. If καὶ ἡμεῖς were to be retained, it might be reconstructed as אַף אָנוּ (’af ’ānū, “also we”; cf. Lord’s Prayer, L20).

מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה (HR). On reconstructing τί ποιήσωμεν (ti poiēsōmen, “What might we do?”) with מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה (mah na‘aseh, “What will we do?”), see above, Comment to L2.

L16 אַל תַּחְמֹסוּ (HR). The verb διασείειν (diaseiein, “to shake violently,” “to intimidate”) is extremely rare in LXX, occurring once in the Greek-composed 3 Maccabees (3 Macc. 7:21) and once as a variant reading in Job 4:14 as the translation of הִפְחִיד (hifḥid, “cause dread”). In first-century papyri διασείειν is attested with the sense “to extort,” which is the meaning of the verb in Luke 3:14.[52] Here is the fragmentary text of one such document:

[ὀμνύω Τιβέριον Κα]ίσαρα Νέον Σεβαστὸν Αὐτοκράτορα [θεοῦ Διὸς Ἐλευθε]ρ[ίου] Σεβαστοῦ υἱὸν εἶ μὴν [μὴ συνε]ιδέναι με μηδενὶ διασεσειμέ[νωι ἐπὶ] τῶν προκειμένων κωμῶν ὑπὸ [ — ]ος στρατιώτου καὶ τῶν παρ᾽ αὐτοῦ.

I swear by Tiberius Caesar Novus Augustus Imperator, son of the deified Jupiter Liberator Augustus, that I know of no one in the village aforesaid from whom extortions have been made [διασεσειμένωι] by the soldier [ — ] or his agents. (P. Oxy. 240)[53]

The fact that a Roman official in Egypt needed to take an oath attesting to his ignorance of extortion taking place indirectly attests to the prevalence among soldiers of extorting the civilian population.

In Hebrew the verb most often used to refer to extortion is חָמַס (ḥāmas, “do violence,” “extort”). An example of חָמַס in this sense is found in the following critique of the Roman Empire:

מלכות הרשעה הזו גוזלת וחומסת

This wicked empire robs and extorts [חוֹמֶסֶת]…. (Gen. Rab. 65:1 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 2:713])

Adopting חָמַס for HR seems particularly appropriate given the use in DSS of the phrases הוֹן חָמָס (hōn ḥāmās, “wealth of extortion”; 1QS X, 19) and הוֹן אַנְשֵׁי חָמָס (hōn ’anshē ḥāmās, “wealth of men of extortion”; 1QpHab VIII, 11) to refer to ill-gotten treasures, and given the Baptist’s proximity to Essene thought.[54]

L17 וְאַל תַּעֲשֹׁקוּ אָדָם (HR). In LXX the verb συκοφαντεῖν (sūkofantein, “to slander”) usually occurs as the translation of עָשַׁק (‘āshaq, “oppress,” “take advantage”).[55] Since עָשַׁק fits the context of Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations, and having found no better alternative, we have adopted it for HR. Below we cite examples in which עָשַׁק (“oppress”) is associated with חָמַס (“extort”):

טוב מי שהוא עושה צדקה מעוטה משלו ממי שהוא גוזל וחומס ועושק ועושה צדקות גדולות משל אחרים

Better is one who performs a little charity from his own property than one who robs and extorts [חוֹמֵס] and oppresses [עוֹשֵׁק] and does a lot of charity from the property of others. (Eccl. Rab. 4:5 §1)

ראה את בני אדם בעונותיהן שהן עושקין וגוזלין וחומסין זה בזה

He saw the sons of Adam in their sins, that they were oppressing [עוֹשְׁקִין] and robbing and extorting [חוֹמְסִין] one another. (Eliyahu Rabbah §[15]16 [ed. Friedmann, 75])

The noun אָדָם (’ādām, “person”) in L17 represents our reconstruction of μηδείς (mēdeis, “no one”), which occurs in L16. Elsewhere we have reconstructed μηδείς with אִישׁ (’ish, “man”).[56]

L18 וְתִתְרַצּוּ בְּאָפְסַנְיוֹתְכֶם (HR). In LXX the verb ἀρκεῖν (arkein, “to suffice”) is rare, but sometimes occurs as the translation of the root [no_word_wrap]מ-צ-א[/no_word_wrap] with the sense of “enough” or “sufficient” (Josh. 17:16; cf. Num. 11:22). We have not succeeded in finding examples of this usage of [no_word_wrap]מ-צ-א[/no_word_wrap] in MH, however, and have therefore sought an alternative for our reconstruction. Another possibility would be to reconstruct John’s exhortation as יִהְיוּ דַי לָכֶם (yihyū dai lāchem, “let them be enough for you”), but such a reconstruction does not greatly resemble the Greek text. We have therefore preferred to construct ἀρκεῖν with הִתְרַצֶּה (hitratzeh), which has the meaning “be satisfied” when aided by the preposition -בְּ (be-, “in,” “with”). Reconstructing with the reflexive הִתְרַצֶּה mirrors the middle/passive form of ἀρκεῖν in Luke 3:14 and allows for a word-for-word correspondence between GR and HR.

An example of -הִתְרַצֶּה בְּ with the meaning “be satisfied with” occurs in the following rabbinic statement:

מתיר את הפס ומתרצה בכסף

He opens his palm [for a bribe] and is satisfied with [-מִתְרַצֶּה בְּ] silver. (Gen. Rab. 78:12 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 2:931])

The noun ὀψώνιον (opsōnion, “provision,” “pay”) occurs 3xx in LXX, but only in books for which there is no Hebrew parallel (1 Esd. 4:56; 1 Macc. 3:28; 14:32). In the ancient papyri this term usually occurs with reference to a soldier’s keep or allowance while in active service, rather than to the payment he was given upon discharge,[57] and the same holds true in early Jewish and Christian writings (1 Macc. 14:32; 1 Cor. 9:7). Lightfoot noted long ago that ὀψώνιον entered the Hebrew language as אָפְסַנְיָא (’ofsanyā’, “provision,” “supply for an army”).[58] The earliest attestation of this loanword from Greek is found in the Mishnah, in an exposition of the commands pertaining to Jewish kings:

וְכֶסֶף וְזָהָב לֹא יַרְבֶּה לּוֹ אֶלָּא כְּדֵי שֶׁיִּתֵּן אֶפְסֶנְיָיא

…and silver and gold he must not amass for himself [Deut. 17:17], but [he may amass wealth] in order to give provision [אֶפְסֶנְיָיא] [to his soldiers]. (m. Sanh. 2:4)

Another early example is found in a tannaic midrash on Exodus:

מלך בשר ודם עומד במלחמה ואינו יכול לזון את חיילותיו ולא לספק להם אופסניות

A king of flesh and blood engages in warfare and he is not able to feed his troops or to supply them with provisions [אוֹפְסַנְיוֹת]. (Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Shirata chpt. 4 [ed. Lauterbach, 1:190])[59]

Reconstructing with אָפְסַנְיָא seems preferable not only because this term is specific to soldiers, and therefore fits the context of Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations, but also because we would have expected to find the noun μισθός (misthos, “wage”) in Luke 3:14 if the underlying Hebrew text had used the more generic term שָׂכָר (sāchār, “wage”).[60]

Redaction Analysis[61]

| Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations | |||

| Luke | Anthology | ||

| Total Words: |

73 | Total Words: |

68 |

| Total Words Identical to Anth.: |

64 | Total Words Taken Over in Luke: |

64 |

| % Identical to Anth.: |

87.67 | % of Anth. in Luke: |

94.12 |

| Click here for details. | |||

The ease with which Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations reverts to Hebrew suggests that the author of Luke copied this pericope from Anth. with a high degree of fidelity. The few changes that he made to Anth.’s wording were stylistic improvements, such as the use of the imperfect tense (L1, L3, L12), the replacement of a simple verb with a compound form (L5), and the addition of conjunctions (L2, L7, L13). Such changes made the story easier for fluent Greek speakers to listen to; they did not affect the essential meaning of the story as it had appeared in Anth.

Results of This Research

1. Should the soldiers who came to John the Baptist be identified as Jews or Gentiles? Josephus informs us that there were Jewish soldiers who served King Herod the Great and his successors, so there certainly were Jewish soldiers in the vicinity at the time John was proclaiming his immersion of repentance for the release of sins. Moreover, John’s exhortation to the soldiers presumes a certain baseline (i.e., exclusive worship of Israel’s God) that could not be assumed of Gentiles, not even of Gentile God-fearers.[62] Without strong evidence to the contrary, it is best to assume that the soldiers John the Baptist addressed were of Jewish extraction. Thus the suggestion, which has occasionally been put forward, that John’s baptism of soldiers somehow prefigured the Gentile mission stands on very shaky historical ground.

2. What inferences should be drawn from the fact that John did not require the soldiers to forsake their military service? Christian theologians have conscripted John the Baptist’s tacit acceptance of military service in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations in polemics over whether Christians are permitted to engage in warfare. Martin Luther’s statement is typical: “There can be no doubt that it was his [i.e., John the Baptist’s—DNB and JNT] task to point to Christ, witness for him, and teach about him; that is to say, the teaching of the man who was to lead a truly perfected people to Christ had of necessity to be purely New Testament and evangelical. John confirms the soldiers’ calling, saying that they should be content with their wages. Now if it had been un-Christian to bear the sword, he ought to have censured them for it and told them to abandon both wages and sword, else he would not have been teaching them Christianity aright.”[63] In this defense of military service, as in so much else, Luther echoed the opinions of St. Augustine.[64]

The approach taken by Luther and Augustine is, however, methodologically unsound. John the Baptist was not a Christian, nor even a follower of Jesus, and there is no reason to assume that John the Baptist shared all of Jesus’ opinions or that Jesus shared all of John’s. Indeed, Jesus was quite explicit that, although he held John the Baptist in high esteem, he did not regard him as a participant in his own redemptive movement, the Kingdom of Heaven (Matt. 11:11; Luke 7:28; see Yeshua’s Words about Yohanan the Immerser). Might John’s tolerance of military service, which is difficult to reconcile with Jesus’ ethic of love for one’s enemies and turning the other cheek, have been one of the dividing issues between John the Baptist and Jesus?

It is interesting to observe that prior to the reign of Constantine, and continuing for sometime thereafter, John the Baptist’s instruction to the soldiers was regarded as sub-Christian, in other words, the teaching of a wise and holy man but not equal to that of Jesus’ teaching, which was incumbent upon all his followers. Tertullian, a third-century Church father, drew a distinction on the issue of military service between the biblical heroes of the pre-Christian past and Jesus’ new covenant teaching: “One soul cannot be due to two masters—God and Caesar. And yet Moses carried a rod, and Aaron wore a buckle, and John (Baptist) is girt with leather,[65] and Joshua the son of Nun leads a line of march; and the People warred: if it pleases you to sport with the subject. But how will a Christian man war, nay, how will he serve in peace, without a sword, which the Lord has taken away? For albeit soldiers had come unto John, and had received the formula of their rule…still the Lord, afterward, in disarming Peter, unbelted every soldier” (On Idolatry §19).[66] Similarly, a church order from the fourth or fifth century entitled Testamentum Domini (or “Testament of our Lord”) had this to say about candidates for Christian baptism: “If anyone be a soldier or in authority, let him be taught not to oppress or to kill or to rob, or to be angry or to rage and afflict anyone. But let those rations suffice him which are given to him. But if they wish to be baptized in the Lord, let them cease from military service or from the [post of] authority, and if not let them not be received” (Testamentum Domini 2:2).[67] According to this source, soldiers admitted for pre-baptism instruction were to be held to the standard demanded by John the Baptist, but in order to be baptized as Christians, soldiers were required to forsake military service.[68]

Returning to the question at hand, regarding what inferences ought to be drawn from John’s tacit acceptance of Jewish military service, we believe that the Baptist’s stance reflects his kinship with the Essenes. The Essenes believed that taking open and active measures to change the political status quo was forbidden, since God had ordained the times and the jurisdiction of the powers that be. As such, Herod the Great, whose paranoia drove him to execute members of his own family, regarded the Essenes as harmless, despite their refusal to make oaths of loyalty to his throne (Ant. 15:368-371). According to Essene doctrine, the members of the sect were to show complete submission to the authorities while clinging to their resentment and grievances in their heart, storing them up for the day of vengeance. For Essene pacifism was conditional; the War Scroll documents their vision of military victory over the Sons of Darkness in the final cosmic battle between God and Belial.

Unlike the Essenes, John the Baptist did not require his followers to withdraw from society, but apparently he did maintain the Essene doctrine of submission to the ruling authorities. Outside the confines of the sectarian community, submission took on a different mode: the authorities could be obeyed not only from outside the government, “like someone oppressed before one domineering him” (1QS IX, 22-23), but also from within. According to John, soldiers who were already serving the ruling authorities should continue to carry out their duties, but not exploit their power for personal gain.

Conclusion

In Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations the people in John’s audience ask him what types of action constituted the fruit worthy of repentance that he demanded. His answers reflect a negative attitude toward wealth and an ideology of patient submission to authorities reminiscent of Essene doctrines.

[/private] Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Notes

- For abbreviations and bibliographical references, see “Introduction to ‘The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction.’” ↩

- This translation is a dynamic rendition of our reconstruction of the conjectured Hebrew source that stands behind the Greek of the Synoptic Gospels. It is not a translation of the Greek text of a canonical source. ↩

- On the audience’s question τί ποιήσωμεν (ti poiēsōmen, “What might we do?”) as a follow up to the Baptist’s demand to ποιήσατε καρπὸν ἄξιον τῆς μετανοίας (poiēsate karpon axion tēs metanoias, “Do/make fruit worthy of repentance”; Matt. 3:8; cf. Luke 3:8), see E. H. Scheffler, “The Social Ethics of the Lucan Baptist (Lk 3:10-14),” Neotestamentica 24.1 (1990): 21-36, esp. 27; J. Liebenberg, “The Function of the Standespredigt in Luke 3:1-20: A Response to E H Scheffler’s The Social Ethics of the Lucan Baptist (Lk 3:10-14),” Neotestamentica 27.1 (1993): 55-67, esp. 60-62. ↩

- See Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance, Comment to L1-2. ↩

- Cf. Kazen, 232 n. 128. ↩

- Other scholars, too, have attributed Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations to the source common to Luke and Matthew. See Plummer, Luke, 90; Marshall, 142. Cf. Knox, 2:4; Davies-Allison, 1:311. ↩

- The material on John the Baptist in Luke 7 is an example of a large block of material copied from Anth. without intrusions from FR. See our introduction to the “Yohanan the Immerser and the Kingdom of Heaven” complex. ↩

- See Foakes Jackson-Lake, 1:103; Scheffler, “The Social Ethics of the Lucan Baptist (Lk 3:10-14),” 28. ↩

- J. Duncan M. Derrett (“The Baptist’s Sermon: Luke 3,10-14,” Bibbia e Oriente 37.3 [1995]: 155-165) suggested that the text upon which the Baptist’s exhortations are based is Exod. 23:1-13, with special attention to the Sabbatical Year commands in Exod. 23:11. While this suggestion would cohere with our impression that John the Baptist was motivated by a Sabbatical/Jubilee ideology, his reliance upon Exod. 23:1-13 in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations is difficult to verify. ↩

- Pace Hartwig Thyen, “ΒΑΠΤΙΣΜΑ ΜΕΤΑΝΟΙΑΣ ΕΙΣ ΑΦΕΣΙΝ ΑΜΑΡΤΙΩΝ,” in The Future of our Religious Past: Essays in Honour of Rudolf Bultmann (ed. James M. Robinson; trans. Charles E. Carlston and Robert P. Scharlemann; New York: Harper & Row, 1971), 131-168, esp. 136-137. See Meier, Marginal, 2:40-42. ↩

- Cf. Tomson, If This Be, 131. ↩

- Other scholars, too, have noted the similarities between the portrayals of John in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations and in the writings of Josephus. See Foakes Jackson-Lake, 1:106; Bundy, 49 §3; David Flusser, “The Baptism of John and the Dead Sea Sect,” in his Jewish Sources in Early Christianity: Studies and Essays (Tel Aviv: Sifriat Poalim, 1979), 81-112, esp. 83-84 (in Hebrew); Meier, Marginal, 2:61-62. ↩

- Cf., e.g., Ernst Bammel, “The Baptist in Early Christian Tradition,” New Testament Studies 18 (1971-1972): 95-128, esp. 105-106; Brent Kinman, “Luke’s Exoneration of John the Baptist,” Journal of Theological Studies 44.2 (1993): 595-598. ↩

- Cf. David Flusser, “The Half-shekel in the Gospels and the Qumran Community” (Flusser, JSTP1, 327-333, esp. 333). ↩

- Cf. LHNS, 11 §3. A textual variant in Codex Bezae reads ἐπηρώτησαν (epērōtēsan, “they asked”), exactly as in our reconstruction. If Codex Bezae preserves the original reading of Luke 3:10, then it was not the author of Luke, but a later scribe, who made the stylistic improvement by replacing ἐπηρώτησαν (“they asked”) with ἐπηρώτων (“they were asking”). ↩

- Cf. LHNS, 11 §3. ↩

- On the secondary nature of ἵνα μὴ…σωθῶσιν in Luke 8:12, see Four Soils interpretation, Comment to L34. ↩

- See George E. Rice, The Alteration of Luke’s Tradition by the Textual Variants in Codex Bezae (Ph. D. dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, 1974), 50-52. ↩

- According to Lindsey, the Anthologizer (i.e., the creator of Anth.) did not change the wording of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua. ↩

- See Scheffler, “The Social Ethics of the Lucan Baptist (Lk 3:10-14),” 25-26. ↩

- In Gen. 4:10, for instance, τί ἐποίησας (“What have you done?”) is the translation of מֶה עָשִׂיתָ (“What have you done?”). Likewise, in Gen. 27:37 τί ποιήσω (“What might I do?”) is the translation of מָה אֶעֱשֶׂה (“What will I do?”). ↩

- The question τί ποιήσωμεν also occurs as the translation of מַה נַּעֲשֶׂה in Judg. 21:7, 16; 1 Kgdms. 5:8; 6:2; 2 Kgdms. 16:20; 2 Chr. 20:12; Song 8:8. In NT the question τί ποιήσωμεν appears in Acts 2:37; 4:16. ↩

- See LHNS, 11 §3. ↩ ↩

- On the clothing worn by first-century Jews, see Shmuel Safrai, “Religion in Everyday Life” (Safrai-Stern, 2:793-833, esp. 797-798); Dafna Shlezinger-Katzman, “Clothing” (OHJDL, 362-381). ↩

- See Shlezinger-Katzman, “Clothing” (OHJDL, 368). ↩

- Text according to Emmanuel Miller, ed., Origenis Philosophumena (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1851). ↩

- On Hippolytus’ source of information regarding the Essenes, see Morton Smith, “The Description of the Essenes in Josephus and the Philosophumena,” Hebrew Union College Annual 29 (1958): 273-313; Geza Vermes and Martin D. Goodman, The Essenes According to the Classical Sources (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1989), 62-63. For a different view, see Albert I. Baumgarten, “Josephus and Hippolytus on the Pharisees,” Hebrew Union College Annual 55 (1984): 1-25. ↩

- Since it was his intention to demonstrate how the Essenes were in error, Hippolytus had no reason to “Christianize” the Essenes by suggesting that they adhered to the teachings of John the Baptist (Luke 3:11) or to the instructions Jesus gave to the apostles (Matt. 10:10; Mark 6:9; Luke 9:3). ↩

- But see Smith, “The Description of the Essenes in Josephus and the Philosophumena,” 290. ↩

- Cf. David Flusser, “Jesus’ Opinion about the Essenes” (Flusser, JOC, 150-168, esp. 162-163). ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 2:915. The sole instance where μεταδιδόναι occurs as the translation of a Hebrew term, that term is הִשְׁבִּיר (hishbir, “purchase grain”; Prov. 11:26), which is not suitable for HR in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations. ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 1:231. ↩

- Additional examples of מִי שֶׁיֵּשׁ/אֵין לוֹ מַה יֹּאכַל occur in m. Moed Kat. 3:4; m. Ned. 4:7, 8; 5:6; t. Moed Kat. 1:11. ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 2:993. ↩

- On the insertion of καί after δέ as an editorial trait of the author of Luke, see Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance, Comment to L17. ↩

- On reconstructing διδάσκαλος with רַב, see Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, Comment to L5. ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 2:1201. ↩

- See LSJ, 1460-1461. ↩

- On the discussion of the collectors of tolls and the poll tax in t. Bab. Metz. 8:26, see Call of Levi, Comment to L68. ↩

- Additional examples of -יוֹתֵר מִמַּה שֶּׁ are found in m. Ket. 3:9 and t. Bab. Bat. 2:20. ↩

- See Gill, 7:339. ↩

- For a discussion on the rabbinic debate over evading tolls, see Louis Ginzberg, “The Significance of the Halachah for Jewish History,” in his On Jewish Law and Lore (New York: Atheneum, 1970), 86-89. ↩

- See Jastrow, 92. ↩

- A variant form of the loanword for “soldier,” סְטַרְטְיוֹט (seṭarṭeyōṭ) (see Jastrow, 973) instead of אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹט (’isṭeraṭyōṭ) as in the previous examples, is also attested:

ב″ו מכתיב לו סטרטיוטין גבורים בריאים כדי ללבוש קסדא ושריון וכלי זיין והקב″ה הכתיב סטרטיוטין שלו שאינן נראין שנא′ עושה מלאכיו רוחות

Flesh and blood enlists for himself soldiers [סְטַרְטְיוֹטִין] who are brave and healthy so that they can wear helmets and mail and bear arms, but the Holy One, blessed is he, enlists soldiers [סְטַרְטְיוֹטִין] who are not seen, as it is said, he makes his messengers winds [Ps. 104:4]. (Exod. Rab. 15:22)

Since this is the only source in which we have located the form סְטַרְטְיוֹט, and since this source is late compared to the others we have cited, we have preferred the spelling אִיסְטְרַטְיוֹט for HR. ↩

- Tertullian (mid-second to mid-third cent. C.E.), for instance, appears to have assumed that the toll collectors and soldiers who came to John the Baptist were Gentiles, since he contrasted them with the “sons of Abraham” (On Modesty chpt. 10). More recently, the identification of the soldiers as Gentiles has been tentatively put forward by J. Green (180). ↩

- Cf. Montefiore, TSG, 2:387; Fitzmyer, 1:470; Davies-Allison, 308 n. 38. ↩

- Cf. Christopher M. Tuckett, “John the Baptist in Q,” in his Q and the History of Christianity: Studies on Q (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1996), 107-137, esp. 115. ↩

- See Plummer, Luke, 92; Jeremias, Theology, 48 n. 3, 110; Marshall, 143; Nolland, Luke, 1:150. Jeremias’ argument that στρατευόμενος (stratevomenos) refers to police whereas στρατιώτης (stratiōtēs) refers to soldiers is weakened by the fact that Josephus used the term στρατευόμενος to refer to soldiers (cf., e.g., J.W. 5:555; 6:54; Ant. 11:46; 19:357; 20:176). The term στρατευόμενος also refers to a soldier in 2 Tim. 2:4. ↩

- On Jewish military service in the Roman period, see Shimon Applebaum, “Jews and Service in the Roman Army,” Roman Frontier Studies: Proceedings of the 7th International Congress, Tel Aviv 1967 (1971): 181-184; idem, “The Legal Status of the Jewish Communities in the Diaspora” (Safrai-Stern, 1:420-463, esp. 458-460). Schoenfeld’s accusation that “the participation of Jews in the Roman military is a topic that is underemphasized or frankly ignored by historians” applies to “Appelbaum [sic.],” who “claims that Jews in the Roman army were ‘renegades,’” is wholly unjustified. Applebaum’s use of the term “renegade” (“Jews and Service in the Roman Army,” 182), as any careful reader of his article will immediately agree, does not reflect his own value judgment, but echoes the vocabulary of an ancient source (Gen. Rab. 82:8 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 2:984-985], cited above) that refers to an apostate Jew who became a soldier during the Hadrianic persecutions. See Andrew J. Schoenfeld, “Sons of Israel in Caesar’s Service: Jewish Soldiers in the Roman Military,” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 24.3 (2006): 115-126, quotation on 116. ↩

- From Josephus (Life §46) and rabbinic sources (y. Pes. 6:1 [39b]) we hear of inhabitants of Bathyra who are active in Jerusalem. If the solders mentioned in Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations came from Bathyra, the Galilee was certainly closer to home than Jerusalem. ↩

- In addition to Jewish soldiers in the service of Herodian rulers, Josephus mentions a Jewish military colony in Egypt at Leontopolis, which existed from the time of Antiochus IV Epiphanes until shortly after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem (see J.W. 7:420-436; Ant. 13:62-73, 284-287, 351-355; 14:131-132). We also learn from Josephus that in the first half of the first century C.E. the Parthian king Artabanus III made two Jewish brothers military commanders in Mesopotamia (Ant. 18:310-370). ↩

- See Moulton-Milligan, 153. ↩

- Text and translation according to Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, eds. and trans., The Oxyrhynchus Papyri: Part II (London: Egypt Exploration Fund, 1899), 184. ↩

- On the anti-imperialist critique implied by the Essene slogans הוֹן חָמָס and הוֹן אַנְשֵׁי חָמָס, see David Flusser, “The Roman Empire in Hasmonean and Essene Eyes” (Flusser, JSTP1, 175-206, esp. 194-197). ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 2:1301. ↩

- On reconstructing μηδείς with אִישׁ, see Sending the Twelve: Conduct on the Road, Comment to L77. ↩

- See Moulton-Milligan, 471; Chrys C. Caragounis, “ΟΨΩΝΙΟΝ: A Reconsideration of Its Meaning,” Novum Testamentum 16.1 (1974): 35-57, esp. 42. ↩

- See Lightfoot, 3:52. Caragounis (“ΟΨΩΝΙΟΝ: A Reconsideration of Its Meaning,” 38) noted that ὀψώνιον entered Latin as obsonium or opsonium, so it appears that this was an international word that easily crossed linguistic boundaries. ↩

- The plural form אָפְסַנְיוֹת also occurs in Sifre Deut. §328 (ed. Finkelstein, 378). ↩

- On μισθός as the Greek equivalent of שָׂכָר, see Sending the Twelve: Conduct in Town, Comment to L97. ↩

-

Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations Luke’s Version Anthology’s Wording (Reconstructed) καὶ ἐπηρώτων αὐτὸν οἱ ὄχλοι λέγοντες τί οὖν ποιήσωμεν ἀποκριθεὶς δὲ ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς ὁ ἔχων δύο χιτῶνας μεταδότω τῷ μὴ ἔχοντι καὶ ὁ ἔχων βρώματα ὁμοίως ποιείτω ἦλθον δὲ καὶ τελῶναι βαπτισθῆναι καὶ εἶπον πρὸς αὐτόν διδάσκαλε τί ποιήσωμεν ὁ δὲ εἶπεν πρὸς αὐτούς μηδὲν πλέον παρὰ τὸ διατεταγμένον ὑμῖν πράσσετε ἐπηρώτων δὲ αὐτὸν καὶ στρατευόμενοι λέγοντες τί ποιήσωμεν καὶ ἡμεῖς καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς μηδένα διασείσητε μηδὲ συκοφαντήσητε καὶ ἀρκεῖσθε τοῖς ὀψωνίοις ὑμῶν καὶ ἐπηρώτησαν αὐτὸν οἱ ὄχλοι λέγοντες τί ποιήσωμεν ἀποκριθεὶς δὲ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς ὁ ἔχων δύο χιτῶνας δότω τῷ μὴ ἔχοντι καὶ ὁ ἔχων βρώματα ὁμοίως ποιείτω ἦλθον δὲ τελῶναι βαπτισθῆναι καὶ εἶπον πρὸς αὐτόν διδάσκαλε τί ποιήσωμεν ὁ δὲ εἶπεν πρὸς αὐτούς μηδὲν πλέον παρὰ τὸ διατεταγμένον ὑμῖν πράσσετε ἐπηρώτησαν δὲ αὐτὸν στρατευόμενοι λέγοντες τί ποιήσωμεν καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς μηδένα διασείσητε μηδὲ συκοφαντήσητε καὶ ἀρκεῖσθε τοῖς ὀψωνίοις ὑμῶν Total Words: 73 Total Words: 68 Total Words Identical to Anth.: 64 Total Words Taken Over in Luke: 64 Percentage Identical to Anth.: 87.67% Percentage of Anth. Represented in Luke: 94.12% ↩

- A Gentile God-fearer might revere Israel’s God in addition to his or her own ancestral deities. On diversity of practice among God-fearing Gentiles, see Paula Fredriksen, “‘If It Looks like a Duck, and It Quacks like a Duck…’: On Not Giving Up the Godfearers,” in A Most Reliable Witness: Essays in Honor of Ross Shepard Kraemer (ed. Susan Ashbrook Harvey et al.; Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2015), 25-33. ↩

- Martin Luther, “Temporal Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed (1523),” in Luther’s Works (55 vols.; ed. Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut T. Lehmann; Saint Louis: Concordia; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1958-1986), 45:98. ↩

- See Augustine, Epistle 138 2:15; Epistle 189 §4; Reply to Faustus the Manichæan 22:74. ↩

- The items borne by the biblical heroes roughly correspond to articles of a Roman soldier’s uniform. ↩

- Translation adapted from The Ante-Nicene Fathers (10 vols.; ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, Allan Menzies; repr. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1980-1986), 3:73. ↩

- Translation according to The Testament of Our Lord, Translated into English from the Syriac with Introduction and Notes (trans. James Cooper and Arthur John MacLean; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1902), 118. ↩

- On varying attitudes toward military service in the early centuries of the Christian Church, see Henry J. Cadbury, “The Basis of Early Christian Antimilitarism,” Journal of Biblical Literature 37 (1918): 66-94; Alan Kreider, “Military Service in the Church Orders,” Journal of Religious Ethics 31.3 (2003): 415-442. ↩