Luke 14:1-6

(Huck 168; Aland 214; Crook 255)[1]

וַיְהִי בְּבֹאוֹ לְבֵיתוֹ שֶׁלְּאֶחַד מֵרָאשֵׁי הַפְּרוּשִׁים וַיְהִי יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת וְהִנֵּה אָדָם אִדְרוֹפִּיקוֹס לְפָנָיו וַיַּעַן יֵשׁוּעַ וַיֹּאמֶר [לַסּוֹפְרִים וְ]לַפְּרוּשִׁים לֵאמֹר יֵשׁ בַּשַּׁבָּת לְרַפְּאוֹת אִם לָאו וַיְרַפְּאֵהוּ וַיִּפְטְרֵהוּ [לְשָׁלוֹם] וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם מִי בָּכֶם נָפַל בְּנוֹ לְתוֹךְ הַבּוֹר וְאֵינוֹ מַעֲלֶה אוֹתוֹ בְּיוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת וְלֹא יָכְלוּ לַעֲנוֹת אֶת דְּבָרָיו אֵלֶּה

And it happened as Yeshua came to the home of one of the leaders of the Pharisees—and it happened to be the day of rest—that a man who was suffering from an accumulation of bodily fluids that caused his limbs and abdomen to swell was right there in front of him. And Yeshua responded and addressed the scribes and the Pharisees, asking them, “Is there a duty to provide medical treatment on the Sabbath, or not?” And he healed the man and dismissed him in full health. Then he said to them, “Who among you, if his son fell into a cistern and was liable to drown, would not pull him up to save him on the Sabbath? As in that case, so in this!” And they were not able to answer his arguments.[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Man With Edema click on the link below:

| “Banquet in the Kingdom of Heaven” complex |

| Man With Edema ・ Invite Those Who Cannot Repay You ・ Great Banquet parable ・ Closed Door ・ Coming From All Directions ・ First and Last ・ Waiting Maidens parable |

Story Placement

Since Luke’s account of the healing of the man with edema—severe swelling of the abdomen and/or limbs due to the retention of bodily fluids—makes no mention of followers attached to Jesus, it is likely that this episode took place early in Jesus’ public career, prior to his calling of full-time disciples. Another indication that this episode took place early in Jesus’ career is his interaction with the Pharisees. When this story takes place the Pharisees are still exhibiting curiosity about Jesus as they attempt to determine whether his teaching was compatible with their approach to Judaism. After Jesus and his teachings had become more widely known, the Pharisees’ interest in Jesus would likely have waned, so the probability is that Man with Edema takes place at a relatively early stage in Jesus’ career. Perhaps this incident took place during an early tour of Judea, when Jesus seems to have had numerous interactions with Pharisees. In view of this possibility, we included Man with Edema in the section of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua entitled “Teaching and Healing in Yehudah.”

We have also made Man with Edema the opening scene of a narrative-sayings complex entitled “Banquet in the Kingdom of Heaven.” The sayings included in this complex (e.g., Open Invitation, First and Last) are aimed at pricking the social conscience of Jesus’ audience. In these sayings, Jesus foresees that the dawning of God’s redeeming reign will involve a shattering of the status quo. Through Jesus’ work of healing, exorcism and the forgiveness of sin, God was reordering an unjust society that had excluded the poor, the non-conforming and the disabled from receiving the blessings enjoyed by the elite. Jesus challenged his audience to embrace this righting of social inequities (i.e., the radical practice of tzedakah) or else be excluded from the blessings of God’s reign both now and in the eschatological future (cf. Coming From All Directions, Waiting Maidens parable).

Man with Edema affords a suitable setting for such a discourse by providing an audience of the correct socio-economic background—the leader of the Pharisees and his guests probably did not belong to the ruling class, but were well-off compared to subsistence farmers, day laborers and the destitute—that was not entirely receptive to Jesus’ message. The healing of the man with edema on the Sabbath could easily have brought to the fore the issues of social justice and God’s redeeming reign, which were so dear to Jesus’ heart but which exacerbated the underlying tensions between Jesus and the Pharisees. Thus, although our placement of this pericope is merely conjectural, we have made Man with Edema the opening scene of the “Banquet in the Kingdom of Heaven” complex. For an overview of the “Banquet in the Kingdom of Heaven” complex, click here.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

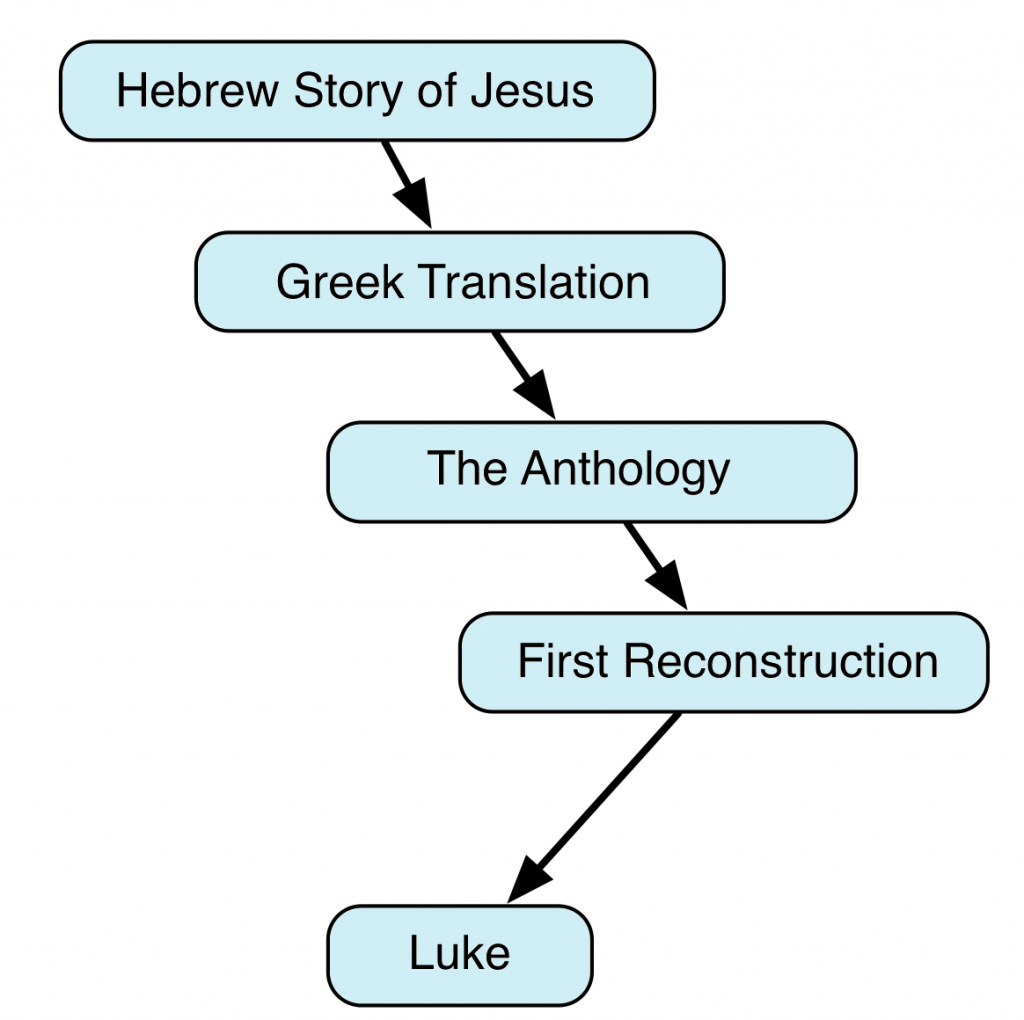

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

Man with Edema is a pericope that is unique to the Gospel of Luke. As such, we cannot measure its level of verbal identity with the Matthean parallel, as we would in a Double Tradition (DT) pericope, to determine on which source the author of Luke depended for Man with Edema. Neither can we cite the quantity of Lukan-Matthean “minor agreements” against Mark as an indicator of Luke’s source, as we might in a Triple Tradition (TT) pericope. We can, however, use the presence or absence of overt Hebraisms, the ease or difficulty of retroversion to Hebrew, and the presence or absence of vocabulary typical of the First Reconstruction to help us identify Luke’s source.

Lindsey described Luke’s first source, the Anthology (Anth.), as a highly Hebraic source characterized by translation Greek, while he described Luke’s second source, the First Reconstruction (FR), as an epitome of Anth. with a more polished Greek style. Therefore, we do not expect to find many overt Hebraisms in pericopae the author of Luke copied from FR, and FR pericopae should put up a degree of resistance to retroversion to Hebrew, while the opposite should be true for pericopae copied from Anth. In addition, FR pericopae can be expected to include vocabulary typical of the First Reconstructor’s writing style. While the absence of such distinctive vocabulary cannot prove that a pericope did not come from FR, the presence of such distinctive vocabulary is a fairly reliable indicator that FR was its source.

When these criteria are applied to Man with Edema, the results are somewhat mixed. Man with Edema does include some overt Hebraisms (καὶ ἐγένετο + time marker [“and it happened when”; L1] + finite verb [ἦσαν; L5 / ἦν; L7]]; φαγεῖν ἄρτον [“to eat bread”] in L4; καὶ ἰδού [“and behold”] in L6; καὶ ἀποκριθεὶς…εἶπεν [“and answering…he said”] in L8-9) as well as hellenized Hebrew vocabulary (σάββατον [sabbaton, “Sabbath” = שַׁבָּת ⟨shabāt⟩] in L3, L10 and L17; Φαρισαίος [Farisaios, “Pharisee” = פָּרוּשׁ ⟨pārūsh⟩] in L2 and L9).[3] Likewise, most of Man with Edema reverts quite smoothly to Hebrew. This evidence tends to favor Anth. as the source for this pericope. On the other hand, in Man with Edema we do encounter vocabulary and themes that are typical of pericopae we have identified as stemming from FR. Thus the verb ἐπιλαμβάνειν (epilambanein, “to take hold”) in L12 also occurs in the FR version of Greatness in the Kingdom of Heaven (Luke 9:47) and twice in Tribute to Caesar (Luke 20:20, 26), which we believe to have originated from FR.[4] Similarly, the verb παρατηρεῖν (paratērein, “to watch,” “to observe”), which occurs in L5, is also found in Tribute to Caesar (Luke 20:20), as well as in Man’s Contractured Arm (Luke 6:7), a likely candidate for an FR pericope. A third verb that is characteristic of FR pericopae, ἰσχύειν (ischūein, “to be strong”) used in the sense of “to be able,” occurs in L18. Another term in Man with Edema that might be regarded as FR terminology is νομικός (nomikos, “legal expert”; L9).[5] In addition, the silence of Jesus’ opponents (L11) is a distinctive theme that occurs in both Man with Edema (L11) and Tribute to Caesar (Luke 20:26), which probably stems from FR. On balance, therefore, it appears that the author of Luke took Man with Edema from FR.[6]

Many scholars regard Man with Edema either as a doublet of Man’s Contractured Arm (Matt. 12:9-14; Mark 3:1-6; Luke 6:6-11) or as a Lukan creation modeled after Man’s Contractured Arm.[7] Of these two possibilities the latter is more likely, since the differences in detail between the two stories would seem to be too great to qualify Man with Edema and Man’s Contractured Arm as doublets. Although both stories concern the issue of healing on the Sabbath, the settings are entirely different (Man’s Contractured Arm takes place publicly in a synagogue, Man with Edema privately at an individual’s home), as are the maladies from which the sufferers are healed (a dried-up hand versus a man swollen with bodily fluids).[8] It is hard to imagine how two stories so different in detail could have evolved from a single origin.[9] But it is also difficult to imagine the author of Luke simply inventing Man with Edema. The author of Luke had already incorporated a handful of similar Sabbath controversies into his Gospel (Lord of Shabbat [Luke 6:1-5]; Man’s Contractured Arm [Luke 6:6-11]; Daughter of Avraham [Luke 13:10-17]), so it is doubtful that he would have found it necessary or desirable to invent one more. Moreover, the specific circumstance of a man with severe swelling is unique. The Hebrew Scriptures do not foreshadow the healing of persons with edema, the healing of this malady is not mentioned in Second Temple Jewish literature, nor anywhere else in the New Testament.[10] What, then, would have prompted the author of Luke to describe the healing of a man with edema in particular? The easiest explanation is that Man with Edema did not spring from the author of Luke’s imagination; he knew of this healing from a source that reported an actual event in the life of Jesus.

The distinctiveness of Man with Edema and Man’s Contractured Arm notwithstanding, in Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm Jesus asks a halakhic question (Matt. 12:11-12a) similar to that which Jesus asks in Man with Edema (Luke 14:5). Both questions inquire about what someone would do on the Sabbath for a living creature that fell into a cistern. By contrast, the Markan and Lukan versions of Man’s Contractured Arm lack this kind of argument. How is it that Matthew’s Man’s Contractured Arm and Luke’s Man with Edema came to include such similar questions? Scholars have suggested that either the author of Matthew took Jesus’ argument from Man with Edema (which the author of Matthew otherwise omitted) and inserted it into his version of Man’s Contractured Arm,[11] or that both the author of Matthew and the author of Luke knew an unattached saying about healing on the Sabbath and each author independently inserted it into different contexts.[12] While these suggestions are theoretically possible, four important considerations weigh against them.

First, if the authors of Luke and Matthew really did independently insert this halakhic question into contexts they deemed appropriate, it is a remarkable coincidence that both authors chose to insert the question into a debate about the propriety of healing on the Sabbath and not some other work. Fleddermann claimed that “From the rhetorical question the reader can easily reconstruct a scene in which Jesus heals on the sabbath, faces opposition, and defends his action,”[13] but this is not self-evident. Neither Matthew’s rhetorical question nor Luke’s refers explicitly to healing. The rhetorical questions would fit just as easily, or perhaps even better, into controversies about what to do for a person who falls into a cistern on the Sabbath, or about what may be done for a person whose house collapses upon them on the Sabbath. How, then, do we explain the Lukan-Matthean agreement to include these halakhic questions in stories pertaining to healing on the Sabbath?

Second, although the general outlines of the halakhic questions are similar, the actual wording is quite different.[14] There is minimal verbal identity between the two questions, and the words that are identical are only the most generic (εἶπεν [“he said”], ὑμῶν [“of you”], εἰς [“into”] and καί [“and”]). More terms are rough equivalents (e.g., ἐμπέσῃ [“might fall in”] / πεσεῖται [“will fall”]; πρόβατον [“sheep”] / βοῦς [“ox”]; ἐγερεῖ [“will raise”] / ἀνασπάσει [“will pull up”]; τοῖς σάββασιν [“on the Sabbaths”] / ἐν ἡμέρᾳ τοῦ σαββάτου [“on the day of the Sabbath”]).[15] However, other terms are by no means equivalent (a son cannot be equated with a sheep!), and the mechanics of the halakhic argument Jesus makes in the two questions are different. In Matthew 12:11-12a Jesus makes a kal vahomer argument (what you would do for a mere sheep, you must certainly do for a human being), whereas in Luke 14:5 Jesus argues by analogy (what you would do for your son, you should equally do for this man).[16] The contrasting terms (human vs. beast) and the divergent functions of the argument indicate that the two halakhic questions are distinct.

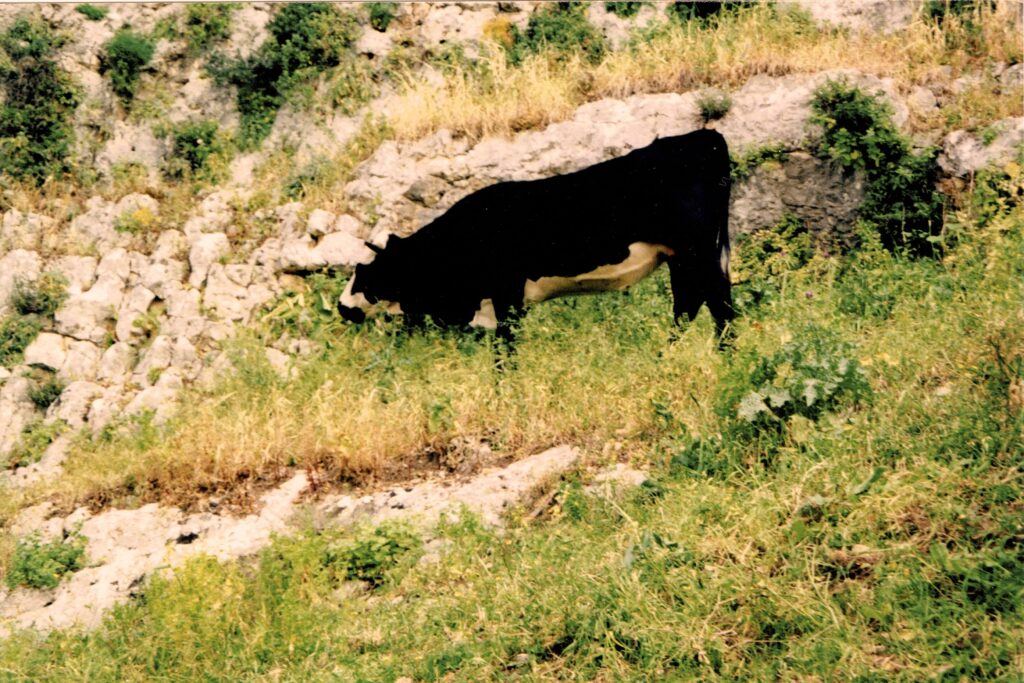

Third, not only do the halakhic questions imply different styles of argumentation, each argument appears to be tailored to the specifics of each man’s case.[17] In Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm the point of comparison in the halakhic question is that neither the sheep in the cistern nor the man with a useless hand are able to keep themselves alive. Both have to rely on aid from others. Therefore, since it is permitted to help a stranded animal to keep itself alive (perhaps by buoying it up [see below]) on the Sabbath, then it is all the more permissible to enable the man to sustain himself by healing his hand on the Sabbath. The point of comparison in the halakhic question found in Man with Edema is different. Both the child in the cistern and the man swollen with bodily fluids are threatened by water.[18] Just as it is permitted on the Sabbath to save one’s son from drowning in water external to his body by hauling him out of a cistern, so it is permitted to save the man from succumbing to the accumulation of fluids inside his body by healing him on the Sabbath. Thus, the way each question is crafted to address the specific circumstances of each man’s case warns against regarding these two questions as different versions of a single original saying.

Fourth, while it might be supposed that the authors of Matthew and Luke were individually responsible for adapting Jesus’ halakhic question to the contexts in which they now appear, the presuppositions underlying the questions turn out to be halakhicly valid—an outcome we would not expect if the differences between Luke 14:5 and Matt. 12:11-12a were merely the byproduct of Lukan and Matthean redaction. Thus, in Matt. 12:11-12a Jesus asks the Pharisees[19] who among them having a sheep that fell into a cistern on the Sabbath would not take hold of it and raise it. The very question about what to do when one’s domesticated animal falls into a cistern on the Sabbath is discussed both in the Dead Sea Scrolls and in rabbinic literature. The sectarians at Qumran adopted a harsh stance on this issue, disallowing any action to be taken on behalf of the fallen animal (CD XI, 13-14; 4Q265 7 I, 6-8). On the other hand, the rabbinic sages, who were the heirs of the Pharisees, adopted a more moderate stance. They allowed a person to do what was necessary to prevent the animal from dying in the cistern until the Sabbath was over, whereupon they could pull the animal out (t. Shab. 14:3).[20] Later discussions specified that life-sustaining measures might include placing cushions under an animal to buoy it up (b. Shab. 128b).[21] Now, despite numerous modern translations that suggest otherwise, Matt. 12:11-12a does not say anything about hauling the sheep out of the cistern. The verb the author of Matthew used to describe what may be done for the sheep is ἐγείρειν (egeirein), a verb that properly means “to raise up from a lying position” or “to elevate,”[22] an action which, as we have just seen, the Pharisaic-rabbinic tradition permitted to be carried out on the Sabbath for a sheep that has fallen into a cistern. Similarly, in Luke 14:5 Jesus asks who among his audience would not pull up his son from a cistern if his son had fallen into one on the Sabbath. This scenario, too, is contemplated in ancient Jewish sources. Even the Qumran sectarians allowed for a person to be hauled out of a cistern on the Sabbath.[23] The only restriction they placed on such a rescue is that tools and implements designed for the purpose were prohibited; a person could, however, use his clothes as a makeshift rope (CD XI, 16-17; 4Q265 7 I, 6-8).[24] The rabbinic sages were far more permissive. They permitted any means necessary to save an endangered life on the Sabbath (cf. t. Shab. 15:11-13).[25] Since the rabbinic sages were heirs to the Pharisaic tradition, we may safely suppose that the Pharisees with whom Jesus engaged in halakhic debate would have conceded that they would, indeed, pull up their son from a cistern if he had fallen therein on the Sabbath. But it beggars belief to suppose that, in the course of their redactional activity, each evangelist accidentally formulated questions with halakhicly sound presuppositions.

Indeed, it appears that the opposite is what actually took place. Redactional interventions on the part of the authors of Matthew and Luke marred the halakhic validity of both questions. In Matt. 12:11 the words οὐχὶ κρατήσει αὐτό (ouchi kratēsei avto, “would he not take hold of it [i.e., the sheep]”) suggest that the author of Matthew misunderstood ἐγείρειν (egeirein) as meaning “haul out” instead of “raise,” “elevate” or, possibly, “buoy up.”[26] Similarly, in Luke the addition of ἢ βοῦς (ē bous, “or ox”) undermines the validity of Jesus’ question. Everyone from the Pharisees to the Essenes would have conceded that, yes, they would pull their son out of a cistern on the Sabbath. But neither the Essenes nor the Pharisees would have agreed that they would pull an ox or any other animal out of a cistern.[27] The Essenes would have left the animal to live or die as Providence allowed, while the Pharisees would have taken measures to keep the animal alive in the cistern, but would not have pulled it out.[28] We suspect that it was the author of Luke who marred Jesus’ argument by importing “ox” into Man with Edema from Daughter of Avraham, which mentions untying an ox or a donkey on the Sabbath for the purpose of leading it to water (Luke 13:15).

Since both the author of Luke and the author of Matthew demonstrated their lack of halakhic sophistication through their redactional activity,[29] they are unlikely to have composed questions with halakhic presuppositions that are so nearly correct. Whoever formulated the questions the evangelists incorporated into their Gospels possessed a degree of halakhic literacy. In our estimation there is no more likely candidate for such a person as Jesus himself. How is it, then, that only Matthew’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm contains a question superficially similar to the question asked in Man with Edema? We believe the explanation is that Luke’s version of Man’s Contractured Arm stemmed from FR. The First Reconstructor eliminated the question preserved in Matt. 12:11-12a, with the result that Luke transmitted to Mark a version of Man’s Contractured Arm that lacked the halakhic question. The author of Matthew, whose practice was to combine the Markan and Anth. versions of pericopae that occurred in both sources, restored the halakhic question to Man’s Contractured Arm from the Anthology.[30]

Crucial Issues

- From what kind of illness did the man with edema suffer?

- Did healing the man with edema break the Sabbath?

Comment

L1 καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῷ ἐλθεῖν αὐτὸν (GR). Whereas some scholars dismiss the opening lines of Man with Edema as typical of Lukan redaction,[31] it must be noted that καὶ ἐγένετο [no subject] + ἐν τῷ infinitive [time marker] + finite main verb + καὶ ἰδού is both un-Greek[32] and highly Hebraic.[33] Moreover, the author of Luke does not use καὶ ἐγένετο + ἐν τῷ infinitive [time marker] + finite verb anywhere in Acts,[34] where his personal writing style is more evident, so it is more likely that Luke’s καὶ ἐγένετο + ἐν τῷ infinitive [time marker] in L1 reflects the wording of Luke’s source.[35]

וַיְהִי בְּבֹאוֹ (HR). On reconstructing γίνεσθαι (ginesthai, “to be”) with הָיָה (hāyāh, “be”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L1.

On reconstructing ἔρχεσθαι (erchesthai, “to come”) with בָּא (bā’, “come”), see Demands of Discipleship, Comment to L8.

Because we prefer to reconstruct narrative in a biblicizing style of Hebrew, we have reconstructed καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῷ + infinitive with בְּ- + וַיְהִי + infinitive construct. Had we adopted a mixed Biblical/Mishnaic style for our reconstruction, we might have considered וַיְהִי בִּכְנִיסָתוֹ (vayhi bichnisātō, “and it was as he entered”) or וַיְהִי כְּשֶׁנִּכְנָס (vayhi keshenichnās, “and it was as he entered”) for HR, since -בְּ + verbal noun and -וַיְהִי כְּשֶׁ + finite verb had come to replace -בְּ + infinitive construct in Mishnaic Hebrew.[36] However, for כְּנִיסָה (kenisāh, “entering”) we would have expected the verb εἰσέρχεσθαι (eiserchesthai, “to enter”) in Luke 14:1. In LXX the phrase ἐν τῷ ἐλθεῖν (en tō elthein, “in the coming”) occurs several times as the translation of בְּבֹא (bevo’, “at the coming”).[37]

L2 εἰς οἶκόν τινος τῶν ἀρχόντων τῶν Φαρισαίων (GR). We have accepted all of Luke’s wording in L2, which reverts easily to Hebrew, for GR. We have also included the definite article τῶν (tōn, “of the”) attached to Φαρισαίων (Farisaiōn, “Pharisee”), which is omitted in Codex Vaticanus, the base text for our reconstruction, since this omission is easily explained as a scribal error.[38] Some scholars have attributed τῶν ἀρχόντων (tōn archontōn, “of the rulers”) to Lukan redaction, either on the grounds that the author of Luke frequently refers to Jewish authorities as “rulers”[39] or on the grounds that the Pharisaic movement was non-hierarchical,[40] but even non-hierarchical organizations have their prominent members,[41] and Josephus (e.g., Shimon ben Gamliel), rabbinic literature (e.g., Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai) and the New Testament (Gamliel the Elder) mention prominent Pharisees. Indeed, by the time of Jesus the Pharisees were divided into two “houses” or schools organized around two outstanding Pharisees of the first century, Shammai and Hillel. And while it is true that the author of Luke holds certain Jewish rulers responsible for the death of Jesus (Luke 23:13, 35; 24:20; Acts 3:17; 13:27), the Pharisees are conspicuously absent from Luke’s Passion narrative, and therefore these culpable “rulers” ought to be distinguished from the Pharisees.[42] Since the combination “ruler of the Pharisees” does not occur elsewhere in Luke or Acts, this designation cannot be regarded as particularly Lukan.[43]

לְבֵיתוֹ שֶׁלְּאֶחַד מֵרָאשֵׁי הַפְּרוּשִׁים (HR). On reconstructing οἶκος (oikos, “house”) with בַּיִת (bayit, “house”), see Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, Comment to L33.

The possessive structure noun + suffix + -שֶׁלְּ + possessor is more typical of Mishnaic Hebrew than Biblical, but it does occur once in the Hebrew Scriptures (מִטָּתוֹ שֶׁלִּשְׁלֹמֹה [miṭātō shelishlomoh, “Solomon’s bed”; Song 3:7).

On reconstructing τις (tis, “a certain one”) with אֶחַד מִן (’eḥad min, “one of”), see Lord’s Prayer, Comment to L4.

In LXX ἄρχων (archōn, “ruler”) occurs as the translation of several Hebrew terms, but none so often as שַׂר (sar, “prince”). The noun ἄρχων also occurs in LXX as the translation of נָשִׂיא (nāsi’, “prince,” “presiding officer”). Somewhat more frequently, ἄρχων occurs as the translation of רֹאשׁ (ro’sh, “head,” “leader”).[44] As the designation for a prominent Pharisee, רֹאשׁ seems the most probable of the three, since by the late Second Temple period שַׂר had acquired royal connotations[45] and נָשִׂיא would seem to be ruled out on account of its exclusivity (how many nesi’im were there likely to have been at any one time?). The noun רֹאשׁ, on the other hand, is a generic enough term for “a leader of the Pharisees,”[46] since it could be applied to any prominent person.

On reconstructing Φαρισαῖος (Farisaios, “Pharisee”) with פָּרוּשׁ (pārūsh, “Pharisee”), see Call of Levi, Comment to L41.

L3 καὶ ἐγένετο ἡ ἡμέρα τοῦ σαββάτου (GR). We suspect that the single word σαββάτῳ (sabbatō, “on a Sabbath”) may be the First Reconstructor’s abbreviation of a longer phrase in Anth., such as “and it was the Sabbath day.” This suspicion arises from the difficulty of reverting Luke’s wording in L3 to Hebrew[47] and from the First Reconstructor’s epitomizing approach to the Anthology. If Anth. had read something like καὶ ἐγένετο ἡ ἡμέρα τοῦ σαββάτου, it would be understandable why the First Reconstructor would have wanted to eliminate the redundant καὶ ἐγένετο phrase.

וַיְהִי יוֹם הַשַּׁבָּת (HR). On reconstructing γίνεσθαι (ginesthai, “to be”) with הָיָה (hāyāh, “be”), see above, Comment to L1.

On reconstructing ἡμέρα (hēmera, “day”) with יוֹם (yōm, “day”), see Choosing the Twelve, Comment to L1.

On reconstructing σάββατον (sabbaton, “Sabbath”) with שַׁבָּת (shabāt, “Sabbath”), see Teaching in Kefar Nahum, Comment to L21.

Opening a narrative with double וַיְהִי statements is paralleled in the first verse of the book of Ruth:

וַיְהִי בִּימֵי שְׁפֹט הַשֹּׁפְטִים וַיְהִי רָעָב בָּאָרֶץ וַיֵּלֶךְ אִישׁ מִבֵּית לֶחֶם יְהוּדָה לָגוּר בִּשְׂדֵי מוֹאָב

And it was [וַיְהִי] in the days of the judging of the judges, and there was [וַיְהִי] a famine in the land, and a man from Bethlehem of Judah went to live abroad in the fields of Moab…. (Ruth 1:1)

καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῷ κρίνειν τοὺς κριτὰς καὶ ἐγένετο λιμὸς ἐν τῇ γῇ, καὶ ἐπορεύθη ἀνὴρ ἀπὸ Βαιθλεεμ τῆς Ιουδα τοῦ παροικῆσαι ἐν ἀγρῷ Μωαβ

And it was [καὶ ἐγένετο] in the judging of the judges, and there was [καὶ ἐγένετο] a famine in the land, and a man from Bethlehem of Judah went to live abroad in the field of Moab…. (Ruth 1:1)

L4 φαγεῖν ἄρτον (Luke 14:1). The phrase “to eat bread,” when used pars pro toto for “to eat a meal,” is often regarded as a Semitism.[48] As such, we might expect φαγεῖν ἄρτον (fagein arton, “to eat bread”) to have been present in Anth. However, it is difficult to fit this phrase into our Hebrew reconstruction, and it seems possible that either the First Reconstructor or the author of Luke imported this phrase from the exclamation in Luke 14:15 (μακάριος ὅστις φάγεται ἄρτον ἐν τῇ βασιλείᾳ τοῦ θεοῦ [“Blessed is whoever will eat bread in the Kingdom of God!”]).[49] Either writer could have inserted this phrase into Man with Edema in order to create greater unity among the pericopae included in Luke 14:1-24. Since Man with Edema does not require Luke’s wording in L4 to make sense, and since it is difficult to accommodate to HR, we have excluded φαγεῖν ἄρτον from GR and an equivalent from HR.

L5 καὶ αὐτοὶ ἦσαν παρατηρούμενοι αὐτόν (Luke 14:1). Although it would by no means be impossible to revert Luke’s wording in L5 to Hebrew,[50] there are two reasons why we regard the statement that “they were watching him” to be the product of the First Reconstructor’s redactional activity. First, the notice that “they were watching him” is a disturbing element in the story, since although from the context it is clear that “they” must refer to the Pharisees,[51] the presence of a group of Pharisees on the scene has not yet been mentioned (they first appear in Luke 14:3 [L9]). This disturbance gives the impression that Luke’s wording in L5 is a later insertion. Second, the verb παρατηρεῖν (“to watch closely”) occurs only three times in the Gospel of Luke,[52] and each instance is in an FR pericope (Man’s Contractured Arm [Luke 6:7]; Man with Edema [Luke 14:1]; Tribute to Caesar [Luke 20:20]),[53] so the scrutiny of Jesus’ behavior is probably a theme introduced by the First Reconstructor.

It is not surprising to discover that the First Reconstructor added the theme of scrutiny to controversy narratives. Elsewhere we have found that the First Reconstructor was writing at a time of increased tension between the early believers and the wider Jewish community.[54] The introduction of the scrutiny motif into stories about Jesus probably reflects the increased and unwelcome scrutiny the early believers received from their fellow countrymen, who looked askance at the believers’ openness to Gentiles at a time when militant nationalist sentiment was running high.[55]

Since we believe the First Reconstructor is responsible for the wording in L5, we have omitted the notice about the scrutiny of Jesus from GR and HR.

L6-7 καὶ ἰδοὺ ἄνθρωπος ὑδρωπικὸς ἔμπροσθεν αὐτοῦ (GR). Although some scholars consider καὶ ἰδού in L6 to be redactional,[56] we have found that the author of Luke (and possibly the First Reconstructor before him) had a tendency to eliminate ἰδού (idou, “behold!”),[57] so it is unlikely that either writer would have added it to Man with Edema. It is more probable that καὶ ἰδού in L6 survives from Anth.[58]

On the other hand, we regard Luke’s pronoun τις (tis, “a certain one,” “someone”) in L6 and his verb ἦν (ēn, “was being”) in L7 as redactional additions, which the First Reconstructor supplied in order to improve the style of his source.[59]

וְהִנֵּה אָדָם אִדְרוֹפִּיקוֹס לְפָנָיו (HR). On reconstructing ἰδού (idou, “behold!”) with הִנֵּה (hinēh, “behold!”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L6.

On reconstructing ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos, “person,” “human”) with אָדָם (’ādām, “person,” “human”), see Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, Comment to L12.

The adjective ὑδρωπικός (hūdrōpikos, “having hūdrōps”), from the noun ὕδρωψ (hūdrōps, “swelling,” “edema”), is rendered as “dropsy” in many English Bible translations.[60] However, since “dropsy” is more or less antiquated in today’s English, we prefer to use the current medical term “edema” for the condition here described.[61] Edema is an accumulation of bodily fluids around the internal organs or in the extremities that results in severe distention.[62]

It may be possible to be a little more specific regarding the ailment from which the man with edema suffered. Ancient medical writers described two kinds of ὕδρωψ, one a generalized swelling of the bodily tissues (anasarca), and the other a localized swelling of the abdomen (ascites). Thus, in the works of Hippocrates (≈ fifth century B.C.E.) we read:

Ὑδρώπων δύο μὲν φύσιες, ὧν ὁ μὲν ὑπὸ τῇ σαρκί ἐγχειρέων γίγνεσθαι ἄφυκτος, ὁ δὲ μετʼ ἐμφυσημάτων, πολλῆς εὐτυχίης δεόμενος

Of edemas [ὑδρώπων] there are two varieties. One is beneath the tissues [i.e., anasarca—JNT and DNB], which, when it occurs, is incurable. The other is accompanied with inflation of the stomach; it requires much good luck to overcome. (Hippocrates, Regimen in Acute Diseases [Appendix] §52)[63]

Similarly, Oribasius, writing in the fourth century C.E., referred to two types of edema:

Καὶ κατακειμένους μὲν ἐγκρύψομεν τούς τε ἀσθματικοὺς καὶ ῥευματιζομένους θώρακα καὶ πλευρὰ καὶ στομαχικοὺς καὶ καχεκτικοὺς, καὶ κατὰ σάρκα ὑδρωπικούς· καθεζομένους δ’ ὑδρωπικῶν μὲν τοὺς ἀσκίτας, καὶ εἰ δέοι, τυμπανίας

In a lying position we bury [in sand as a medical treatment—JNT and DNB] those with shortness of breath and those discharging fluids from the chest, sides, and stomach. Likewise those who are in a poor bodily state, and who have edema [ὑδρωπικούς] throughout the tissues [i.e., anasarca—JNT and DNB]. But [we place] in a sitting position those with edema [ὑδρωπικῶν] who have a distended abdomen [ascites], and, if necessary, those whose bellies are stretched out like a drum. (Oribasius, Collectiones medicae 10:9)[64]

Such “edemas” are symptomatic of serious, and likely terminal, conditions such as advanced liver or heart disease.[65]

We would have been at a loss as to how to reconstruct ὑδρωπικός (hūdrōpikos, “having edema”) were it not for the fact that ὑδρωπικός entered Mishnaic Hebrew as אִדְרוֹפִּיקוֹס (’idrōpiqōs, “having edema”), as we see in the following example:

ומים תיכן במידה, אדם הזה משוקל, חציו מים וחציו דם. בשעה שהוא זוכה לא המים רבין על הדם ולא הדם רבה על המים. ובזמן שהוא חוטא פעמים שהמים רבין על הדם ונעשה אידרופיקיאוס, פעמים שהדם רבה על המים ונעשה מצורע

And water he weighs out by measure [Job 28:25]. This person is balanced: half of him is water and half of him is blood. When he does right, the water does not exceed the blood and the blood does not exceed the water. But when he sins, sometimes the water exceeds the blood and he becomes one experiencing edema [אִדְרוֹפִּיקוֹס].[66] Other times, the blood exceeds the water and he becomes one experiencing scale disease. (Lev. Rab. 13:2 [ed. Margulies, 1:323-324])

This passage from Leviticus Rabbah attests to the ancient view that human bodily fluids consist of blood and water, a view that also finds expression in the New Testament (John 19:34). In addition, this passage demonstrates an awareness that the swelling of those suffering from edema is caused by an excess of “water” in the body. Such awareness is important, because it is the threat to life caused by water that is the point of comparison between the man with edema and the child in the cistern.

Other rabbinic sources attest that edema was regarded as potentially life-threatening,[67] another crucial point of comparison between the child fallen in the cistern and the man with edema.[68] Referring to edema as הִדְרוֹקָן (hidrōqān), the Babylonian form of אִדְרוֹפִּיקוֹס,[69] we read:

שלשה מתין כשהן מספרין ואלו הן חולי מעיין וחיה והדרוקן

Three die while they are giving explanations, and these are they: one with intestinal problems, a woman giving birth, and one with edema [וְהִדְרוֹקָן]. (b. Eruv. 41b)

According to this statement, a person with edema is likened to a woman giving birth in that either could die suddenly, even while giving instructions to the people around them.[70] Rabbinic halakhah allowed for Sabbath restrictions to be overridden for the sake of a woman in labor (m. Shab. 18:3). The point Jesus argues here is that Sabbath restrictions should also be eased for the sake of a person with edema.

Two issues occasionally raised in scholarly literature in connection with edema are 1) the association of edema with immorality and sin,[71] and 2) the association of edema with ritual impurity.[72] In Greek and Latin sources edema is often associated with the vice of overindulgence.[73] Behind the association of edema with sin is the observation that, despite their swelling up with excess bodily fluids, persons suffering from edema often exhibited unquenchable thirst. Thus edema became a metaphor for insatiable appetites. Occasionally we also find that edema was regarded as a consequence of lavish living.[74] In rabbinic sources edema is sometimes regarded as a punishment for sin (cf. b. Shab. 33a), as we saw in the quotation from Leviticus Rabbah above (“But when he sins, sometimes the water exceeds the blood and he becomes one experiencing edema”; Lev. Rab. 13:2). But the sages were aware that edema could be the result of numerous other causes such as bowel obstruction (b. Ber. 25a)[75] and extreme hunger, and an important rabbinic sage, Shmuel ha-Katan, was said to have suffered from edema (b. Shab. 33a). Thus, while it is true that edema, like any other affliction or unhappy circumstance, could be viewed as a punishment for sin or the consequence of intemperate living, it was not possible to work backwards from this or any other misfortune to the conclusion that the sufferer had brought their misfortune upon themselves, was guilty of sin, or under God’s judgment. The cruel fact that the innocent suffer was as well known in the ancient world as it is today.[76] Since the man with edema in Luke 14:1-6 is not accused of sin or lavish living, there is no reason to suppose that the persons involved in witnessing the healing suspected the man’s integrity. The association of edema with overindulgence or punishment for sin is not operative in Man with Edema and probably does not play a significant role in the joining of Places of Honor (Luke 14:7-11), Open Invitation (Luke 14:12-14) or the Great Banquet parable (Luke 14:15-24) to Man with Edema (Luke 14:1-6) in Luke’s Gospel.[77] The importance of the man’s edema in our pericope is not symbolic but practical. His potentially life-threatening ailment caused by the accumulation of excess fluid in his body is the basis of comparison between the man’s case and that of the child in the cistern, who is in danger of drowning.

While there are some grounds for discussing the association of edema with vice and divine punishment, the grounds for linking edema with ritual impurity are exceedingly flimsy. Contrary to the assertion that the presence of the man with edema would have imperiled the ritual purity of the meal,[78] on the grounds that edema produced impure bodily discharges,[79] edema was caused by the retention of excess bodily fluids and did not result in the seepage of bodily fluids. Even if it had, these bodily fluids would not have been impure. Neither tears, nor sweat, nor saliva, nor urine, nor excrement, nor blood (except for vaginal bleeding) were sources of ritual impurity.[80] Thus, the fact of the man’s edema was no threat to the ritual purity of those who witnessed his healing. The only way the man’s presence could have imparted impurity to the guests is if he were inside with them in the Pharisee’s house and if he died suddenly of the cause of his edema. In such a scenario the impurity of his corpse—not of his edema—would have imparted impurity to the people and the susceptible objects present. And since we cannot assume that the man with edema was indoors with the guests, the dynamics of ritual purity are not a factor in this pericope.[81]

On reconstructing ἔμπροσθεν (emprosthen, “in front of”) with לִפְנֵי (lifnē, “in front of”), see Yeshua’s Thanksgiving Hymn, Comment to L10-11.

Some scholars have wondered what this man was doing at the home of the Pharisee, since he appears not to have been numbered among the guests,[82] for otherwise it is strange that Jesus later dismisses him.[83] While some attribute the man’s admittance to “eastern hospitality,”[84] and others suppose that the man was “planted” at the meal in order to entrap Jesus,[85] Luke 14:1-2 need not imply that the man with edema was inside the Pharisee’s home. Jesus encountered him as he was entering the house, but the man could still have been outside in the street or in a shared courtyard.

L8 καὶ ἀποκριθεὶς Ἰησοῦς (GR). We have accepted all of Luke’s wording in L8 for GR with the exception of the definite article attached to the name of Jesus, which may be a Lukan or FR concession to Greek style. Otherwise, Luke’s wording in L8-9, with its redundant “answering…he said…saying,” is highly Hebraic[86] and not characteristic of the author of Luke’s style.[87] Thus, Luke’s wording in L8 probably reflects that of his source.[88]

Collins made much of the fact that in Luke 14:3 Jesus “replies” without yet having been addressed by anyone,[89] claiming, “It is obvious…that if Jesus replied, he must have been addressed. Since no previous address to Jesus is noted in Luke’s account, it must be assumed that the words to which Jesus replied have been omitted from Luke’s tale.”[90] However, such far-reaching conclusions based on the verb ἀποκρίνειν (apokrinein) are unwarranted. “To respond verbally to a circumstance” is an established meaning of ἀποκρίνειν,[91] so it is not obvious that Jesus must have been verbally addressed. All we can conclude from ἀποκρίνειν is that Jesus was confronted with a situation that elicited from him a verbal response. It is probably best to regard this usage of ἀποκρίνειν in Luke 14:3 as a Hebraism, since there is no dearth of examples of עָנָה (‘ānāh, “answer”) in the Hebrew Scriptures where the response is to a situation rather than a verbal address.[92]

וַיַּעַן יֵשׁוּעַ (HR). On reconstructing ἀποκρίνειν (apokrinein, “to answer”) with עָנָה (‘ānāh, “answer”), see Call of Levi, Comment to L56.

On reconstructing Ἰησοῦς (Iēsous, “Jesus”) with יֵשׁוּעַ (yēshūa‘, “Jesus”), see Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L12.

L9 εἶπεν πρὸς τοὺς [γραμματεῖς καὶ] Φαρισαίους λέγων (GR). In Luke, Jesus’ response is addressed not to the man with edema but to the legal experts and the Pharisees who, evidently, were arriving at the house at the same time as Jesus. Since according to Josephus the Pharisees enjoyed a popular reputation for expertise in legal matters (J.W. 2:162; Ant. 18:15; Life §191),[93] an opinion also expressed in Acts by Paul (Acts 22:3; 26:5),[94] perhaps “the legal experts and the Pharisees” should be interpreted as a hendiadys: “the Pharisees, experts in halakhic matters.”[95]

In any case, for GR we have replaced Luke’s reference to νομικοί (nomikoi, “legal experts”)[96] with a reference to γραμματεῖς (grammateis, “scribes”). We have also placed this reference in brackets because we cannot be entirely certain that this wording occurred in Anth. Uncertainty arises from the fact that νομικός (nomikos) is almost entirely unique to Luke’s Gospel in the synoptic tradition and from the fact that Luke sometimes has νομικός where the Matthean parallel has γραμματεύς (grammatevs, “scribe”).[97] Based on these data it would be easy to conclude that νομικός is a Lukan replacement for γραμματεύς.[98] But these data must be balanced by the additional fact that although the author of Luke used γραμματεύς 4xx in Acts (Acts 4:5; 6:12; 19:35; 23:9),[99] νομικός never occurs there,[100] which suggests that νομικός is not a Lukan term but was taken over from (one of) Luke’s sources.[101] This impression is confirmed by the further fact that nearly all instances of νομικός in Luke’s Gospel appear in pericopae we have identified as stemming from FR.[102] In view of this information it appears likely that νομικός is FR’s substitute for γραμματεύς.[103]

The picture is complicated, however, by the fact that there is a Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark to write νομικός in Torah Expert’s Question (Luke 10:25 ∥ Matt. 22:35; cf. Mark 12:28). This Lukan-Matthean agreement would indicate that at least this one instance of νομικός occurred in Anth.,[104] but to add a further layer of complexity to this already knotty issue, the authenticity of νομικός in Matt. 22:35 (∥ Luke 10:25) is doubted by many text critics. Although νομικός in Matt. 22:35 is firmly attested in NT MSS, it is omitted in some versions and patristic citations, and Matt. 22:35 being the only instance of νομικός in Matthew, scholars plausibly hypothesize that its presence in Matt. 22:35 is due to an early scribal insertion, harmonizing Matt. 22:35 with the Lukan parallel.[105] So it is doubtful that νομικός ever occurred in Anth.

As for Anth.’s version of Man with Edema, FR’s νομικοὺς καί (nomikous kai, “legal experts and”) might stand in the place of Anth.’s γραμματεῖς καί (grammateis kai, “scribes and”), or the First Reconstructor might have inserted νομικοὺς καί into the narrative. Our uncertainty in this regard accounts for our placement of γραμματεῖς καί within brackets.

The rest of Luke’s wording in L9 is unproblematic, and we have accepted it unhesitatingly for GR.

וַיֹּאמֶר [לַסּוֹפְרִים וְ]לַפְּרוּשִׁים לֵאמֹר (HR). On reconstructing εἰπεῖν (eipein, “to say”) with אָמַר (’āmar, “say”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L12.

On reconstructing γραμματεύς (grammatevs, “scribe”) with סוֹפֵר (sōfēr, “scribe”), see Call of Levi, Comment to L41. As with γραμματεῖς καί in GR, so in HR we have placed -לַסּוֹפְרִים וְ (lasōferim ve–, “to the experts in halakhah and”) in brackets.

Despite the unlikelihood that νομικός (“legal expert”) occurred in Anth., it remains tempting to reconstruct νομικός in Man with Edema as בָּקִי בַּהֲלָכָה (bāqi bahalāchāh, “expert in halakhah”),[106] which is as close to a semantic equivalent for νομικός as anyone could hope to find.[107] The term בָּקִי בַּהֲלָכָה is first attested in the Mishnah (m. Eruv. 4:8) to refer to someone who has mastered the technicalities of Sabbath halakhah. This expertise distinguished him from the average observant Jew, who relied upon the bāqi bahalāchāh’s expertise in complex matters, for not everyone was qualified to make the halakhic determinations of the expert. Nevertheless, reconstructing νομικός with בָּקִי בַּהֲלָכָה runs the risk of anachronism, since we cannot be certain that the terminology employed by the rabbinic sages was also used by their Pharisaic forebears.[108] That risk, plus the unlikelihood of νομικός occurring in Anth., weigh against adopting בָּקִי בַּהֲלָכָה for HR.

On reconstructing Φαρισαῖος (Farisaios, “Pharisee”) with פָּרוּשׁ (pārūsh, “Pharisee”), see above, Comment to L2.

On reconstructing λέγειν (legein, “to say”) with אָמַר (’āmar, “say”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L15. We have adopted the Biblical Hebrew form of the infinitive, לֵאמֹר (lē’mor, “to say”), rather than the Mishnaic form לוֹמַר (lōmar, “to say”), because we prefer to reconstruct narrative in a biblicizing style.

L10 ἔξεστιν τῷ σαββάτῳ θεραπεῦσαι ἢ οὔ (GR). In Luke’s Gospel the verb ἐξεῖναι (exeinai, “to be allowed,” “to be fitting,” “to be possible”) occurs exclusively in FR pericopae (Lord of Shabbat [Luke 6:2, 4]; Man’s Contractured Arm [Luke 6:9]; Man with Edema [Luke 14:3]; Tribute to Caesar [Luke 20:22]). This is also true of the phrase ἢ οὔ (ē ou, “or not”), which, in addition to Man with Edema (Luke 14:3), occurs only in Tribute to Caesar (Luke 20:22). Nevertheless, we hesitate to identify these words and phrases as markers of FR redaction.[109] Their use may simply be due to the type of questions posed in these pericopae (“What is or isn’t permissible in a given situation?”), and the terminology could have been taken over from Anth. Since the wording of the question in L10 reverts reasonably well into Hebrew, and since no obvious alternative is evident, we have cautiously adopted Luke’s wording in L10 for GR.

יֵשׁ בַּשַּׁבָּת לְרַפְּאוֹת אִם לָאו (HR). We have reconstructed Luke’s ἔξεστιν + infinitive (“it is allowed/possible to do X”) with the parallel structure יֵשׁ + infinitive (“it is required/advisable/possible to do X”), which is mainly found in Mishnaic Hebrew. A clear example of this usage is found in the statement וּבְכָל מָקוֹם וּמָקוֹם יֵש לַעֲשׂוֹת לְפִי מִנְהָגוֹ (“…and in each and every place it is required to act according to its custom”),[110] but an example of this construction already occurs once in late Biblical Hebrew:

יֵשׁ לַיי לָתֶת לְךָ הַרְבֵּה מִזֶּה

The Lord is able to give [יֵשׁ לַיי לָתֶת] you more than this. (2 Chr. 25:9)

Examples of this kind can also be found in the Mishnah, for instance:

יֶשׁ לִי לִלְמוֹד שֶׁכָּל מַה שֶּׁעָשָׂה רַבָּ′ גַּמְלִיאֵ′ עָשׂוּיִ שֶׁנֶּ′

I am able to learn [יֶשׁ לִי לִלְמוֹד] [from Scripture—JNT and DNB] that everything that Rabban Gamliel did is proper, as it is said…. (m. Rosh Hash. 2:9)

Another clear example is found in the following midrash:

כל קנאה הסמוכה ללמ″ד לשון חיבה, כגון אשר קינא לאלהיו, קנא קנאתי לה′ צבאות, וכל דומיהן, ואם יאמר לך אדם, ויקנאו למשה במחנה, יש להשיב כי גם אותה קנאה של חיבה שהיו מחבבין את הכהונה

Every instance of qin’ah [“jealousy,” “zeal”] that is connected [to what follows—JNT and DNB] with a lamed is an expression of love, such as who was zealous for his God [Num. 25:13], I have been exceedingly zealous for the Lord [1 Kgs. 19:10], and all those like them. And if a person says to you, “And they were jealous of Moses in the camp [Ps. 106:16],” it is necessary to reply [יֵשׁ לְהַשִׁיב] that that, too, was a jealousy of love, for they loved the priesthood. (Sekel Tov, Bereshit, Vayeshev 37:11 [ed. Buber, 1:216])

Compare our reconstruction of ἔξεστιν + infinitive with יֵשׁ + infinitive to our reconstruction of οὐκ ἔξεστιν + infinitve as אֵין + infinitive in Yohanan the Immerser’s Execution, L7.

Reconstructing Luke’s ἔξεστιν + infinitive with יֵשׁ + infinitive affords Jesus’ halakhic question a bit more punch, since it can mean “Is it required to heal on the Sabbath?” rather than “Is it permitted to heal on the Sabbath?” In other words, Jesus could have been asking whether there is a moral obligation to do something for the man suffering from edema, not just whether there might be some way to work around the Sabbath restrictions.

As an alternative, we could reconstruct ἐξεῖναι (exeinai, “to be allowed,” “to be fitting,” “to be possible”) with הוּתָּר (hūtār, “be permitted”).[111] The participial form of this verb is found in rabbinic discussions of what is permissible on the Sabbath:

מותר לכבס מנעל בשבת

It is permitted [מוּתָּר] to wash a shoe on the Sabbath. (b. Zev. 94b)

ת″ר גר תושב מותר לעשות מלאכה בשבת לעצמו כישראל בחולו של מועד

It was taught in a baraita, a resident alien is permitted [מוּתָּר] to do work on the Sabbath for himself like an Israelite on the intermediate days of the festival [of Passover and Sukkot]. (b. Ker. 9a)

We even find a question about what type of medical treatment is permitted on the Sabbath:

אָדָם מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁהָיָה חוֹשֵׁשׁ בְּאָזְנוֹ מַהוּ שֶׁיְּהֵא מֻתָּר לְרַפְּאוֹתוֹ בַּשַּׁבָּת כָּךְ שָׁנוּ חֲכַמִים: כָּל שֶׁסָּפֵק נְפָשׁוֹת דּוֹחֶה אֶת הַשַּׁבָת, וְזוֹ מַכַּת הָאוֹזֶן אִם סַכָּנָה הִיא מְרַפְּאִים אוֹתָהּ בַּשַּׁבָּת.

An Israelite who was suffering in his ear, what is permitted [מֻתָּר] to treat it on the Sabbath? Thus taught the sages: Everything that puts a life in doubt overrides the Sabbath, so this ear affliction, if it is a danger, they heal it on the Sabbath. (Deut. Rab. 10:1 [ed. Merkin, 11:141])

Despite these examples of מוּתָּר, we believe יֵשׁ + infinitive is a better option for HR because it appears Jesus framed the question in terms of a moral obligation (as the rabbinic sages were later to do with regard to pikuah nefesh, the duty of saving a human life on the Sabbath),[112] and not in terms of what it is possible to get away with.

On reconstructing σάββατον (sabbaton, “Sabbath”) with שַׁבָּת (shabāt, “Sabbath”), see above, Comment to L3.

On reconstructing θεραπεύειν (therapevein, “to give medical treatment,” “to heal”) with רִפֵּא (ripē’, “give medical treatment,” “heal”), see Sending the Twelve: Commissioning, Comment to L22-23. We encountered an example of לְרַפְּאוֹת (lerap’ōt), the infinitve of רִפֵּא, in the example from Deuteronomy Rabbah cited above.

In LXX ἢ οὔ (ē ou, “or not”) is appended to numerous questions (all indirect), where it occurs as the translation of אִם לֹא (’im lo’, “if not”), for instance:

לָדַעַת הַהִצְלִיחַ יי דַּרְכּוֹ אִם לֹא

…in order to know whether the Lord granted his road success or not [אִם לֹא; LXX: ἢ οὔ]. (Gen. 24:21)

הַאַתָּה זֶה בְּנִי עֵשָׂו אִם־לֹא

…whether you are my son Esau or not [אִם לֹא; LXX: ἢ οὔ]. (Gen. 27:21)

הַכְּתֹנֶת בִּנְךָ הִוא אִם־לֹא

…whether it is your son’s tunic or not [אִם לֹא; LXX: ἢ οὔ]? (Gen. 37:32)

הֲיֵלֵךְ בְּתוֹרָתִי אִם־לֹא

…whether he will walk in my Torah or not [אִם לֹא; LXX: ἢ οὔ]. (Exod. 16:4)[113]

In Mishnaic Hebrew the opposite alternative attached to a conditional clause was expressed no longer as אִם לֹא but as אִם לָאו (’im lā’v, “if not”).[114] Since we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in a style resembling Mishnaic Hebrew, we have adopted אִם לָאו for HR.

L11 οἱ δὲ ἡσύχασαν (Luke 14:4). We have four reasons for regarding Luke’s wording in L11, which describes the Pharisees’ silence, as an FR addition. First, the statement about the Pharisees’ silence can be omitted without doing damage to the story. The account would still make sense if Jesus had asked a rhetorical question and proceeded to heal the man without waiting for a response from the Pharisees and legal experts/scribes. Second, as we noted in the Conjectured Stages of Transmission discussion above, Jesus’ silencing of his opponents seems to have been a redactional motif of the First Reconstructor. Third, it appears that there is an intentional wordplay in Greek between the statement in L11 that “they were silent (ἡσύχασαν [hēsūchasan])”[115] and “they were not able (οὐκ ἴσχυσαν [ouk ischūsan]) to answer” in L18,[116] and since the verb for “to be able” in L18 is a marker of FR redaction, it was probably the First Reconstructor who created the wordplay by writing οἱ δὲ ἡσύχασαν (“but they were silent”) in L11.[117] Fourth, the style of the wording in L11 is un-Hebraic. Had the wording in L11 been translated from a Hebrew source, we would expect to have found καὶ ἡσύχασαν (kai hēsūchasan, “and they were silent”) or ἡσύχασαν δέ (hēsūchasan de, “but they were silent”), whereas οἱ δὲ ἡσύχασαν represents good Greek style.

It is always possible that the First Reconstructor wrote οἱ δὲ ἡσύχασαν in place of Anth.’s καὶ ἡσύχασαν or ἡσύχασαν δέ, but since the silencing of Jesus’ opponents appears to be an FR motif, this possibility seems remote.[118]

L12 καὶ ἐθεράπευσεν αὐτὸν (GR). It appears that in L12 the First Reconstructor exercised his editorial pen, since both the verbs ἐπιλαμβάνειν (epilambanein, “to take hold”) and ἰᾶσθαι (iasthai, “to heal,” “to effect a cure”) should be regarded as markers of FR redaction.

The verb ἐπιλαμβάνειν occurs with a higher frequency in Luke (5xx) than in the other Synoptic Gospels (Matthew 1x; Mark 1x),[119] but just as importantly, most of the instances of ἐπιλαμβάνειν in Luke occur in pericopae that, on other grounds, have been identified as stemming from FR (Greatness in the Kingdom of Heaven [Luke 9:47]; Man with Edema [Luke 14:4]; Tribute to Caesar [Luke 20:20, 26]). While it is possible that the First Reconstructor wrote ἐπιλαβόμενος (epilabomenos, “taking hold”) in place of λαβόμενος (labomenos, “taking”) in Anth., we think it is more likely that the entire notion of Jesus’ taking hold of the man with edema springs from FR redaction. The taking hold is not an essential part of the story, and its omission does not cause the story to make any less sense. We have, therefore, omitted a participle for “taking” from GR.

With regard to ἰᾶσθαι (iasthai, “to heal,” “to effect a cure”), while it is true that a Lukan-Matthean agreement to use this verb in Centurion’s Slave (Matt. 8:8 ∥ Luke 7:7) proves that it did occur at least once in Anth., and while it is easy enough to revert ἰᾶσθαι to Hebrew,[120] we cannot overlook the facts that not only does ἰᾶσθαι occur with a higher frequency in Luke (11xx) than in Mark (1x) or Matthew (4xx),[121] but many instances of ἰᾶσθαι in Luke occur in pericopae derived from FR (Bedridden Man [Luke 5:17]; Yeshua Attends to the Crowds [Luke 6:18, 19]; Centurion’s Slave [Luke 7:7];[122] Sending the Twelve: Commissioning [Luke 9:2];[123] Man with Edema [Luke 14:4]).[124] It is therefore likely that the high frequency of ἰᾶσθαι in Luke is largely due to his reliance on FR. Moreover, ἰᾶσθαι in L12 appears to be used in contrast to θεραπεύειν in L10 in order to distinguish the question about treating illness from the cure Jesus effected in the man with edema.[125] Such a distinction can be made in Greek, but cannot be so easily done in Hebrew.[126] Therefore, it looks as though the distinction between “cure” and “treatment” entered the story only in the Greek stage of transmission, and is probably a stylistic improvement introduced by the First Reconstructor. Unlike “taking hold,” “he healed him” cannot be omitted without damaging the story. We suspect that ἰάσατο (iasato, “he cured”) is FR’s substitution for Anth.’s ἐθεράπευσεν (etherapevsen, “he healed”),[127] a suspicion that is reflected in GR.

וַיְרַפְּאֵהוּ (HR). On reconstructing θεραπεύειν (therapevein, “to give medical treatment,” “to heal”) with רִפֵּא (ripē’, “give medical treatment,” “heal”), see above, Comment to L10.

L13 καὶ ἀπέλυσεν [αὐτὸν ⟨ἐν εἰρήνῃ⟩] (GR). We have accepted all of Luke’s wording in L13 for GR and added, within brackets, the additional pronoun “him” and the words “in peace.”

We added αὐτόν (avton, “him”) because Hebrew syntax would have required a corresponding object, whether in the form of a pronominal suffix attached to the verb or the direct object marker + pronominal suffix. We think it is likely that either of these Hebrew means of indicating the object would have been translated as αὐτόν and been retained in Anth., but could have been dropped by either the First Reconstructor or the author of Luke.

Our addition of ἐν εἰρήνῃ (en eirēnē, “in peace”) is more speculative, as indicated by the second set of brackets that surround it. To “dismiss” someone “in peace” is a Hebrew expression that we encounter in rabbinic sources (see below) and that surfaces in Luke’s infancy narratives, where Simeon says:

νῦν ἀπολύεις τὸν δοῦλόν σου…ἐν εἰρήνῃ

…now you may dismiss your servant…in peace. (Luke 2:29)

If ἐν εἰρήνῃ was present in Anth., the First Reconstructor could have dropped these words because he did not understand the expression, or because he thought the detail detracted from the tension in the story, which he aimed to increase, or on account of his frequently epitomizing approach to Anth.

וַיִּפְטְרֵהוּ [לְשָׁלוֹם] (HR). In LXX the verb ἀπολύειν (apolūein, “to release,” “to dismiss”) is rarely used in the sense of “to dismiss,”[128] which is surely the sense in which it is intended in Luke 14:4.[129] In the one instance in which ἀπολύειν in this sense occurs as the translation of a Hebrew verb (Ps. 33[34]:1) that verb is גֵּרֵשׁ (gērēsh, “drive out”),[130] which is too harsh for the present context. Another option for HR is the verb פָּטַר (pāṭar, “dismiss”), a verb that is more typical of Mishnaic than Biblical Hebrew, but which occurs once in the Hebrew Scriptures in this sense:

כִּי לֹא פָטַר יְהוֹיָדָע הַכֹּהֵן אֶת הַמַּחְלְקוֹת

…for Yehoyada the priest did not dismiss [פָטַר] the priestly divisions. (2 Chr. 23:8)

An example of פָּטַר in Mishnaic Hebrew occurs in a discussion of the rite of breaking the calf’s neck in order to expunge the guilt of a murder whose perpetrator is unknown:

זִקְנֵי אוֹתָהּ הָעִיר רוֹחֲצִין אֶת יְדֵיהֶן בַמַיִם בִּמְקוֹם עֲרִיפָתָה שֶׁלַּעֲגָלָה וְאומְ′ יָדֵינוּ לֹא שָׁפְכֻה אֶת הַדָם הַזֶּה וְעֵינֵינוּ לא רָאוּ כִי עַל לִיבֵּנוּ עָלַת שֶׁזִקְנֵי בֵית דִּין שׁוֹפְכֵי דָמִים הֵן אֶלָּא שֶׁלֹּא בָא עַל יָדֵינוּ וּפֶטַרְנוּהוּ וְלֹא רְאִינוּהוּ וְהִינִּיחוּהוּ

The elders of that city wash their hands in water in the place of the calf’s neck breaking and they say, Our hands did not shed this blood and our eyes did not see [what happened—JNT and DNB] [Deut. 21:7]. But could it have come into our hearts that the elders of the court were spillers of blood? Rather, [this declaration means] that he [i.e., the murder victim—JNT and DNB] did not come into our hands and we dismissed him [וּפֶטַרְנוּהוּ] [without giving him aid—JNT and DNB], and we did not see him [in need—JNT and DNB] and leave him [to fend for himself—JNT and DNB]. (m. Sot. 9:6)

In neither of these cases cited above do we encounter the idiom “dismissed in peace,” but this is due to the context. In 2 Chr. 23:8 Yehoyada did not dismiss the priestly divisions either in peace or in disarray, and in the rite of the calf the elders proclaim that they did not dismiss the victim without giving him aid, the very opposite of dismissing him in peace. Below are several examples in which the idiom “dismiss in peace” does appear:

ת″ר מעשה בשני בני אדם שנשבו בהר הכרמל…ואמר ברוך שבחר בזרעו של אברהם ונתן להם מחכמתו ובכל מקום שהן הולכים נעשין שרים לאדוניהם ופטרן [והלכו] לבתיהם לשלום

Our rabbis taught [in a baraita]: An anecdote concerning two people who were captured on Mount Carmel…[there ensues a clever exchange between the captives and their captor—JNT and DNB]…And he [i.e., the captor—JNT and DNB] said, “Blessed is the One who chose the seed of Abraham and gave them of his wisdom, and in every place they go they are made princes to their lords!” And he dismissed them [ופטרן] [and they went] to their homes in peace [לשלום]. (b. Sanh. 104a-b)

ויהי בעת ההיא. שיעץ יהודה את אחיו למכור את יוסף: וירד יהודה מאת אחיו כיון שראו אביהן עוסק בשקו ותעניתו אמרו ליהודה מלך הייתה עלינו, ואמרת לנו למכרו, ושמענו לך, ואם היית אומר פטרוהו לשלום, היינו שומעין לך כמו כן

And it happened at that time [Gen. 38:1] when Judah counseled his brothers to sell Joseph and Judah went down from his brothers [Gen. 38:1] when they saw their father in his sackcloth and engaged in his fasting, they said to Judah, “You are king over us, and you told us to sell him. But if you had said, ‘Dismiss him in peace [פטרוהו לשלום]!’ we would likewise have listened to you….” (Sekel Tov, Bereshit, Vayeshev 38:1 [ed. Buber, 1:225])

ובאו אצל שלמה ופטרן לשלום…לקח ממנה ושתה ונתרפא…ופטרו אותו לשלום

And they came to Solomon, and he dismissed them in peace [ופטרן לשלום]. …He took some of it and drank and he was healed…and they dismissed him in peace. (Midrash Tehillim 39:2 [ed. Buber, 255])

In Man with Edema dismissing the cured man “in peace” would primarily refer to the soundness of his body and the fullness of his health.

On reconstructing the noun εἰρήνη (eirēnē, “peace”) with שָׁלוֹם (shālōm, “peace,” “wellbeing,” “wholeness”), see Tower Builder and King Going to War similes, Comment to L21. In LXX the phrase ἐν εἰρήνῃ (en eirēnē, “in peace”) almost invariably occurs as the translation of בְּשָׁלוֹם (beshālōm, “in peace”),[131] but in most examples of “dismiss in peace” expressed with פָּטַר we find לְשָׁלוֹם (leshālōm, “to peace”). Adopting בְּשָׁלוֹם for HR would be acceptable, but since לְשָׁלוֹם appears to have been more common, we have preferred the latter for HR. In any case, the two phrases were interchangeable, as we see in the following example:

בזמן ששני בעלי דינין באין לפני אברהם אבינו לדין ואמר אחד על חבירו זה חייב לי מנה היה אברהם אבינו מוציא מנה משלו ונותן לו ואמר להם סדרו דיניכם לפני. וסדרו דינן. כיון שנתחייב אחד לחבירו מנה אמר לזה שבידו המנה תן המנה לחבירך. ואם לאו אמר להם חלקו מה שעליכם והפטרו לשלום. אבל דוד המלך לא עשה כן אלא עושה משפט תחלה ואחר כך צדקה…בזמן שבעלי דינין באין לדין לפני דוד המלך אמר להם סדרו דיניכם. כיון שנתחייב אחד לחבירו מנה היה מוציא מנה משלו ונותן לו ואם לאו אמר להם חלקו מה שעליכם והפטרו בשלום

When two litigants came before our father Abraham for judgment, and the one said concerning his opponent, “This person owes me a mina!” our father Abraham would take out a mina of his own and give it to him [i.e., to the accused—JNT and DNB] and say to them, “Present your cases before me,” and they presented their case. When one was found to be owing his opponent a mina, he would say to the one who had the mina in his hand, “Give the mina to your opponent.” And if not, he would say to them, “Divide what you have and depart in peace [והפטרו לשלום].” But King David did not do thus, rather he did justice first and afterward mercy…. When two litigants came before King David for judgment, he said to them, “Present your cases.” When one was found to be owing his opponent a mina, he would take out a mina of his own and give it to him. And if not, he would say to them, “Divide what you have and depart in peace [והפטרו בשלום].” (Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version A, §33 [ed. Schechter, 94])

The complete passivity of the man with edema, who has no name, who does not speak, and who takes no action (the man is dismissed, but readers must infer that he actually left), shows that the focus of the story is not on the man or on the miraculous healing per se but on the principle at stake, namely that there is an obligation to give medical treatment, even if doing so overrides the prohibition to do work on the Sabbath.[132]

L14 καὶ εἶπεν πρὸς αὐτοὺς (GR). We have accepted all of Luke’s wording in L14 for GR, but slightly rearranged the words in order to more closely reflect Hebrew word order. The emphatic word order could have been an FR or Lukan improvement.

וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם (HR). On reconstructing εἰπεῖν (eipein, “to say”) with אָמַר (’āmar, “say”), see above, Comment to L9.

L15 τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν υἱὸς εἰς φρέαρ πεσεῖται (GR). We suspect that the author of Luke made two alterations to FR’s wording in L15. First, since in other Anth. and FR pericopae we encounter the phrase τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν (tis ex hūmōn, “who among you?”),[133] we think it is likely that it was the author of Luke who changed this to τίνος ὑμῶν (tinos hūmōn, “of which of you?”), a stylistic improvement.[134] That it was the author of Luke, and not the First Reconstructor, who made this change is supported by our finding that it was the author of Luke who changed τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν to τίνα ἐξ ὑμῶν in Fathers Give Good Gifts, an Anth. pericope (Luke 11:11).[135]

A sentence with a structure similar to our reconstruction is found in the final verse of 2 Chronicles:

|

2 Chr. 36:23 |

GR |

|

τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν ἐκ παντὸς τοῦ λαοῦ αὐτοῦ |

τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν |

|

Who | from | you | from | all | the | people | of him |

Who | from | you |

|

ἔσται ὁ θεὸς αὐτοῦ μετ̓ αὐτοῦ |

υἱὸς εἰς φρέαρ πεσεῖται |

|

will be | the | God | of him | with | him |

a son | into | a well | will fall |

|

καὶ ἀναβήτω |

καὶ οὐκ ἀνασπάσει αὐτὸν |

|

and | let him go up! |

and | not | he will pull up | him…? |

The second alteration the author of Luke made to FR’s wording in L15 was the insertion of ἢ βοῦς (ē bous, “or an ox”) following υἱός (huios, “son”). As we discussed above in the Conjectured Stages of Transmission section, the addition of “or an ox” diminishes the validity of the suppositions behind Jesus’ halakhic question. Not grasping the halakhic implications of his insertion, the author of Luke appears to have added “or an ox,” having picked up the reference to an ox from Daughter of Avraham, in which Jesus makes a similar argument about healing on the Sabbath by appealing to the example of untying an ox or a donkey in order to lead it out to water (Luke 13:15).[136] Probably by his insertion the author of Luke wanted his readers to recall that Jesus had made a similar argument about Sabbath healings before, but not only did the insertion undermine the validity of Jesus’ argument—for Jesus’ contemporaries were likely to have agreed that a child (but not an ox!) could be pulled from a cistern on the Sabbath—it created such an unusual pairing—a child is not really comparable to an ox—that it has generated numerous emendations to the text, both ancient and modern.[137]

The most common textual variant in Luke 14:5 is to read ὄνος (onos, “donkey”) instead of υἱός (huios, “son”). Although this reading makes for a more natural pair, it totally invalidates Jesus’ halakhic argument, for unlike a son, neither an ox nor a donkey could be pulled out of a cistern on the Sabbath. Moreover, it is easy to discern the origin of the reading ὄνος. The scribes who wrote ὄνος in place of υἱός picked up “donkey” from Jesus’ argument in Daughter of Avraham.[138] In other words, the author of Luke succeeded in reminding these copyists of the earlier Sabbath healing story. Nevertheless, because the pairing of “son or ox” borders on the nonsensical, “donkey or ox” still has its champions.[139]

Another variant reading is πρόβατον (probaton, “sheep”) in place of υἱός (huios, “son”). This variant harmonizes the argument Jesus makes in Luke 14:5 with that made in Matt. 12:11-12, in which Jesus refers to buoying up a sheep on the Sabbath.[140]

A modern emendation of the text is to read ὄϊς (ois, “sheep”) in place of υἱός (huios, “son”). This emendation would explain how the two variants, “son” and “sheep,” arose, but this emendation is not attested in any ancient manuscript, and, though ingenious, there are simpler ways to account for the various readings.[141]

Common to all these emendations is the feeling that “son” is the intrusive item in the pair “son or ox,” but “son” is firmly anchored in the textual tradition, and, as the more difficult reading,[142] it is hard to imagine any scribe writing “son” in place of “donkey” or “sheep.” Even among scholars who accept “son” as the original reading we encounter skepticism that the text is correct: there must have been a mistranslation[143] or corruption of the oral tradition before the author of Luke set pen to parchment.[144] We think our solution is more elegant: it is the ox, not the son, that is the alien element. Minus the ox, Jesus finds common halakhic ground with his ancient Jewish contemporaries. Somewhere along the line, someone who was not halakhicly astute inserted “ox,” and because Jesus makes arguments about the care given to animals on the Sabbath in other places, readers have assumed that it was “son” that must be a mistake. We suspect it was the author of Luke who made the insertion because, as a Gentile writing for a non-Jewish audience, he was unlikely to understand the finer points of Jesus’ argument.[145] FR, on the other hand, seems to have been composed for mixed congregations of Greek-speaking Jews and Gentiles in Judea, and the First Reconstructor seems to have been fairly well-informed about Jewish matters.

Supposing the author of Luke inserted “or an ox” explains why this item is firmly established in the textual tradition—it is not a later scribal addition. But our supposition that the author of Luke inserted “or an ox” also means that an inspired writer of Scripture made an (halakhic) error. We embrace an understanding of inspiration broad enough to allow for human error and frailty.[146]

מִי בָּכֶם נָפַל בְּנוֹ לְתוֹךְ הַבּוֹר (HR). On the reconstruction of τίς ἐξ ὑμῶν (tis ex hūmōn, “who from you?”) as מִי בָּכֶם (mi bāchem, “who among you?”), see Tower Builder and King Going to War, Comment to L1.

On reconstructing πίπτειν (piptein, “to fall”) with נָפַל (nāfal, “fall”), see Return of the Twelve, Comment to L17. Although Luke’s verb for “to fall” is in the future tense (πεσεῖται [peseitai, “will fall”]), in HR we have put the verb in the perfect tense because in Mishnaic Hebrew conditional sentences not introduced with a particle (such as אִם [’im, “if”]) have the protasis (the “if” clause) in the perfect while the verb in apodosis (the “then” clause”) is either a perfect or a participle,[147] as we see in the following example, which is relevant not only for its grammatical parallel but also for its subject matter:

נפל לבור…עוקרין לו חוליה ויורדין ומעלין אותו משם

[If] someone fell [נָפַל] into a cistern…they break loose [עוֹקְרִין] a section of its entrenchment for him and go down [וְיוֹרְדִין] and bring him up [וּמַעֲלִין] from there. (t. Shab. 15:13; Vienna MS)

The future tense of the Greek verbs in L15 and L16 is probably a concession to Greek style.

On reconstructing υἱός (huios, “son”) with בֵּן (bēn, “son”), see Fathers Give Good Gifts, Comment to L3. To בֵּן we have attached a pronominal suffix despite the absence of the possessive pronoun αὐτοῦ (avtou, “of him”) in GR. It was not uncommon for Greek translators of Hebrew texts to omit possessive pronouns equivalent to the pronominal suffixes attached to nouns.

In LXX φρέαρ (frear, “well,” “cistern”) usually occurs as the translation of בְּאֵר (be’ēr, “well”), although on a few occasions (1 Kgdms. 19:22; 2 Kgdms. 3:26; Jer. 48[41]:7, 9) it occurs as the translation of בּוֹר (bōr, “cistern,” “pit”).[148] The LXX translators more often rendered בּוֹר as λάκκος (lakkos, “pit,” “cistern”) or βόθρος (bothros, “pit,” “hole”) than as φρέαρ (“well”),[149] but ancient Jewish discussions regarding what may be done for living creatures stranded in a hole on the Sabbath show that בּוֹר is the best option for HR:

אל יילד איש בהמה ביום השבת ואם תפול אל בור ואל פחת אל יקימה בשבת…וכל נפש אדם אשר תפול אל מקום מים ואל [בו]ר אל יעלה איש בסולם וחבל וכלי

A man must not help a domesticated animal give birth on the Sabbath day. And if it falls into a cistern [בּוֹר] or into a pit, he may not preserve it[s life][150] on the Sabbath. …And every human that falls into a place of water or into a [cister]n [בּוֹר], a man may not pull him up with a ladder or a rope or a utensil. (CD XI, 13-14, 16-17; corrected on the basis of 4Q271 5 I, 8-11)

בהמה שנפלה לתוך הבור עושין לה פרנסה במקומה בשביל שלא תמות

A domesticated animal that fell into a cistern [הַבּוֹר]: they sustain it where it is,[151] so that it will not die. (t. Shab. 14:3; Vienna MS)[152]

נפל לבור ואין יכול לעלות עוקרין לו חוליה ויורדין ומעלין אותו משם ואין צריך ליטול רשות בית דין

If someone fell into a cistern [לַבּוֹר] and was not able to come up, they break loose a section of the entrenchment for him and go down and bring him up from there. And there is no need to obtain authority to do so from the Bet Din. (t. Shab. 15:13; Vienna MS)

Also pertinent for our discussion are the following statements regarding what may be done with animals on the holy days of Passover, Shavuot, Sukkot and Rosh HaShanah, when regular activities are curtailed, but not quite as strictly as on the Sabbath:

בְּכוֹר שֶׁנָּפַל לַבּוֹר ר′ יְהוּדָה אוֹ′ יֵרֵד מוּמְחֶה וְיִרְאֶה אִם יֶשׁ בּוֹ מוּם יַעֲלֶה וְיִשְׁחוֹט וְאִם לָאו לֹא יִשְׁחוֹט

A firstborn animal that fell into a cistern [לַבּוֹר]: Rabbi Yehudah says, “An expert goes down and inspects. If there is a blemish in it [i.e., the animal—JNT and DNB], he pulls it up and slaughters it. But if not, he does not slaughter it.” (m. Betz. 3:4)[153]

Firstborn kosher animals were to be sacrificed, but if they became blemished, they were no longer acceptable for the altar and could therefore be slaughtered and eaten (Deut. 15:19-23). The presumption of the example above is that it is only permitted to pull up the firstborn animal from the cistern for the purpose of slaughtering it, food preparation being permitted on a holy day but not on the Sabbath.

אותו ואת בנו שנפלו לבור ר′ ליעזר או′ מעלה את הראשון על מנת לשוחטו ושחטו והשיני עושה לו פרנסה במקומו בשביל שלא ימות

A domesticated animal and its young that fell into a cistern [לַבּוֹר]: Rabbi Liezer says, “One pulls up the first [only] in order to slaughter it, and he slaughters it. And the second he sustains it where it is in order that it not die.” (t. Betz 3:2; Vienna MS)

Here, too, the presumption is that the mature animal may only be pulled out of the cistern for the purpose of eating it, which is why it may be slaughtered. Since the young animal is not to be slaughtered, it must be left in the cistern, as on the Sabbath.[154]

Rabbinic sources also contain reports about people who fell into cisterns. One such report describes a scenario similar to that which Jesus described except that the event did not take place on the Sabbath:

ת″ר מעשה בהתו של נחוניא חופר שיחין שנפלה לבור הגדול ובאו והודיעו לרבי חנינא בן דוסא שעה ראשונה אמר להם שלום שניה אמר להם שלום שלישית אמר להם עלתה אמר לה בתי מי העלך אמרה לו זכר של רחלים נזדמן לי וזקן מנהיגו

Our rabbis taught [in a baraita]: An anecdote concerning the daughter of Neḥunya the ditch digger, who fell into a large cistern [לַבּוֹר]. They came and informed Rabbi Ḥanina ben Dosa. The first hour he said to them, “Peace [i.e., all is well].” The second hour he said to them, “Peace.” The third hour he said to them, “She has come up.” He said to her, “My daughter, who brought you up?” She said to him, “A male of the ewes was appointed for me, and an old man was leading it.” (b. Yev. 121b)

In view of the above examples, it would be strange to reconstruct φρέαρ (“well,” “cistern”) with anything other than בּוֹר. Probably the Greek translator’s choice of φρέαρ to render בּוֹר in Man with Edema was dictated by his awareness that the water-filled hole was a point of comparision with the man with edema’s condition, caused by the accumulation of excess fluids.

The above examples also show that “into a cistern” could be reconstructed in a variety of ways: אֶל (הַ)בּוֹר (’el [ha]bōr, “into [the] cistern”), לַבּוֹר (labōr, “[in]to the cistern”), לְתוֹךְ הַבּוֹר (letōch habōr, “[in]to the interior of the cistern”). In LXX we find the phrase εἰς τὸ φρέαρ (eis to frear, “into the well”) occured once as the translation of אֶל תּוֹךְ הַבּוֹר (’el tōch habōr, “into the interior of the cistern”; Jer. 48[41]:7).

L16 καὶ οὐκ ἀνασπάσει αὐτὸν (GR). We have accepted all of Luke’s wording in L16 for GR with the exception of the adverb εὐθέως (evtheōs, “immediately”), which we have found to be the product of Lukan redaction in other pericopae.[155] Otherwise, Luke’s wording in L16 reverts fluently into Hebrew.

Although the verb ἀνασπᾶν (anaspan, “to pull up”) does not occur elsewhere in the synoptic tradition, it does occur once in Acts, where it is used to describe the hoisting up of the sheet into heaven at the conclusion of Peter’s vision (Acts 11:10).[156] Nevertheless, a single instance of ἀνασπᾶν in Acts is hardly sufficient to characterize this verb as especially Lukan. Moreover, “to pull up” is precisely the correct term for Jesus’ halakhic question.

וְאֵינוֹ מַעֲלֶה אוֹתוֹ (HR). On the negation of participles with אֵין in Mishnaic Hebrew, see Segal, 162 §339.

In LXX the verb ἀνασπᾶν (anaspan, “to pull up”) only occurs three times (Amos 9:2; Hab. 1:15; Dan. 6:18) and only twice with a Hebrew equivalent (Amos 9:2; Hab. 1:15).[157] In Hab. 1:15 ἀνασπᾶν occurs as the translation of הֶעֱלָה (he‘elāh, “bring up,” “cause to go up”). The ancient Jewish sources that discuss the pulling up of a person or an animal from a cistern on the Sabbath show that a hif‘il form of ע-ל-ה is the best choice for HR:

אל יעל איש בהמה אשר תפול א[ל ]המים ביום השבת ואם נפש אדם היא אשר תפול אל המים [ביום] השבת ישלח לו את בגדו להעלותו בו וכלי לא ישא [להעלותו ביום] השבת

A man must not pull up [יַעַל] a domesticated animal that falls into the water on the day of the Sabbath. But if it is a human being that falls into the water [on the day of] the Sabbath, he may cast him his clothing to pull him up [לְהַעֲלוֹתוֹ] with it, but he may not take up a utensil [to pull him up on the day of] the Sabbath. (4Q265 7 I, 6-9; DSS Study Edition)

וכל נפש אדם אשר תפול אל מקום מים ואל [בו]ר אל יעלה איש בסולם וחבל וכלי

And every human life that falls into a place of water or into a [cister]n, a man may not pull him up [יַעֲלֶה] with a ladder or a rope or a utensil. (CD XI, 16-17; corrected on the basis of 4Q271 5 I, 10-11)

מפקחין על ספק נפש בשבת והזריז הרי זה משובח ואין צריך ליטול רשות מבית דין כיצד נפל לים ואין יכול לעלות טבע′ ספינתו בים ואין יכול לעלות יורדין ומעלין אותו משם ואין צריך ליטול רשות בית דין נפל לבור ואין יכול לעלות עוקרין לו חוליה ויורדין ומעלין אותו משם ואין צריך ליטול רשות בית דין תינוק שנכנס לבית ואין יכול לצאת שוברין לו דלתות הבית ואפי’ היו של אבן ומוציאין אותו משם ואין צריך ליטול רשות בית