How to cite this article: Joshua N. Tilton and Lauren S. Asperschlager, “The Discomposure of Jesus’ Biography (Reboot): A Modification to Lindsey’s Conjectured Stages of Synoptic Transmission,” Jerusalem Perspective (2025) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2802/].

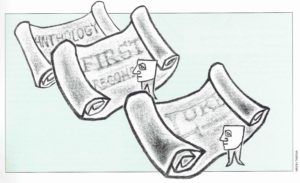

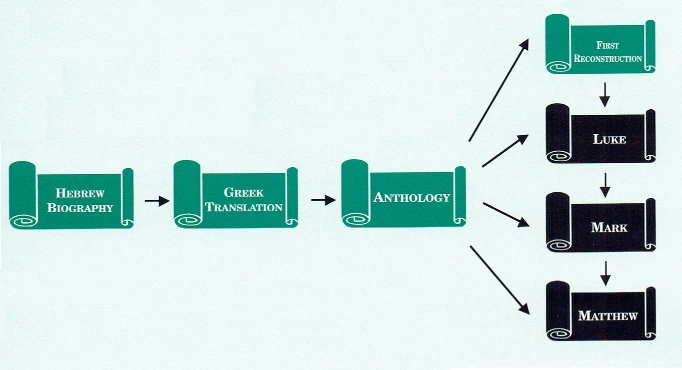

There is much to be said for Robert Lindsey’s hypothesis regarding the origins and interrelationships of the Synoptic Gospels. Lindsey believed that the earliest source of the synoptic tradition was a written Hebrew account of the life and teachings of Jesus, which was subsequently translated into Greek. The Greek tradition branched in two directions. One was a highly Hebraic collection of Jesus’ words and deeds, which was arranged according to theme and genre rather than chronology, such that teachings were separated from the incidents that prompted them, and parables and other illustrations were separated from their teaching contexts. Lindsey called this source “the Anthology.” The other branch was a loosely chronological narrative made up of pericopae selected from the Anthology but paraphrased in stylistically improved Greek. Lindsey referred to this source as “the First Reconstruction” because he regarded it as the earliest written attempt to impose narrative order upon the scattered fragments of tradition.

According to Lindsey, the author of Luke was heir to both of these Greek sources, the Anthology (Anth.) and the First Reconstruction (FR), which he drew upon to compose his own Gospel. His use of two sources with some parallel content accounts for the “Lukan Doublets” and the two types of Double Tradition (DT) pericopae Luke’s Gospel shares with Matthew. Doublets are the result of Luke’s inclusion of both the Anth. and FR versions of a pericope. Type One DT pericopae, which are characterized by remarkably high levels of verbal identity between the Lukan and Matthean parallels, both evangelists copied from Anth. (the only pre-synoptic source known to the author of Matthew), while Type Two DT pericopae, which are characterized by relatively low levels of verbal agreement between Luke and Matthew, are the result of the author of Luke’s dependence on FR parallel to the author of Matthew’s dependence on Anth.

Lindsey believed that Mark was dependent upon Luke, not the other way around as most source critics assume. Lindsey’s reasons for this supposition are, among other things, that Luke’s Gospel lacks many of the most obvious traces of Markan redaction (e.g., the repeated use of εὐθύς, the un-Hebraic use of the historical present, etc.), that Luke’s versions of pericopae generally revert better to Hebrew than the Markan parallels and often preserve more authentically Jewish details, and that the numerous Lukan-Matthean agreements against Mark indicate that both of these evangelists were in touch with non-Markan tradition. Nothing about Luke’s Gospel requires dependence on Mark for its explanation that could not just as well be explained by dependence on Anth. and FR. Lindsey believed that the author of Mark did essentially the same thing to Luke’s Gospel that the First Reconstructor had done to Anth.: the Markan evangelist selected certain pericopae from Luke, paraphrased them, and presented them in his own preferred order.

As for the pericopae in Mark that are unparalleled in Luke, Lindsey believed that some of these may have come from Anth. (e.g., Yohanan the Immerser’s Execution), for Lindsey hypothesized that the Markan evangelist was aware of this source, too, and some are Markan compositions either drawn from oral tradition (e.g., Jesus and a Canaanite Woman) or of his own invention (e.g., Walking on Water).

Lindsey also detected clues that the author of Mark was familiar with stories in Acts, which was composed by the Lukan evangelist. The author of Mark paraphrased some of his pericopae in such a way as to echo the stories in Acts in order to show how Jesus’ story resonated in the tales of the apostles.

Matthew, which preserves many of Mark’s redactional features, Lindsey believed to have been based on Mark and Anth. The author of Matthew’s approach was to blend the parallel Markan and Anth. versions, sometimes adopting the language of Mark, sometimes that of Anth., and sometimes paraphrasing on his own. Non-Markan pericopae in Matthew came almost exclusively from Anth., although there are a few (e.g., Matthew’s Infancy Narrative, the Half Shekel episode) that the author of Matthew drew from oral tradition.

Lindsey’s hypothesis explains why so much of the non-Markan material in Matthew seems so authentic and reverts so well to Hebrew, why Luke’s Gospel (unlike Matthew’s) is so free of Markan redactional traits, and why Mark often seems so strange and exaggerated in its portrayal of Jesus, his followers, and his opponents.

One of the most intriguing of Lindsey’s suggestions is that it may be possible to reconstruct the original literary contexts of Jesus’ deeds, teachings, and illustrations as they had existed in the Hebrew biography of Jesus on the basis of verbal and thematic clues still preserved in the synoptic texts. For instance, the Lost Sheep and Lost Coin similes can be joined to Call of Levi on the basis of their shared themes of repentance and joyful acceptance and on the key phrase “they have no need.”[4] Read together, the story of Levi’s banquet, Jesus’ teaching on his mission to call not the righteous but sinners to repentance, and the similes illustrating God’s joyful acceptance of repentant sinners are mutually illuminating.

However, one of the most puzzling aspects of Lindsey’s hypothesis is why, if there ever existed a Hebrew account of the life and teachings of Jesus in which stories, teachings, and illustrations were presented as literary units, these literary units ever came to be disintegrated and reorganized according to theme and genre. Lindsey believed this disintegration of Jesus’ biography was the work of the Anthologizer, who rearranged the materials he found in the Greek translation of the Hebrew biography of Jesus. He suggested that perhaps the Anthologizer broke the incident-teaching-illustrations complexes apart for didactic purposes, so that catechumens could memorize the content more easily, but this suggestion is not altogether convincing. As Lindsey himself demonstrated, the sayings and illustrations make more sense in their larger literary contexts, and would seem, therefore, to be more easily memorizable when their meaning was more clearly understood.

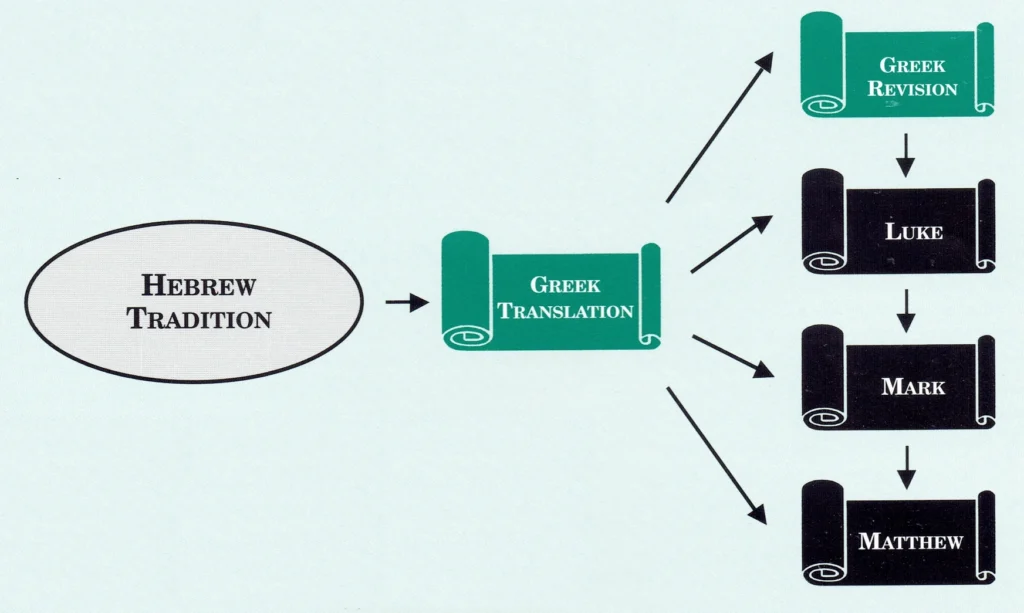

In issue 53 of the Jerusalem Perspective magazine David Bivin proposed an amended form of Lindsey’s hypothesis to better account for what he called the discomposure of Jesus’ biography.[5] Bivin suggested that there never was a written Hebrew account of the life of Jesus, only crystalized oral traditions about the things Jesus had done and said. The first written account was a Greek translation of these traditions, which lacked any coherent narrative structure (≈ Anth.) due to the amorphous nature of the oral Hebrew tradition. A second Greek source attempted to impose a narrative structure onto these translated pericopae (≈ FR). These two sources, which Bivin designated as “the Greek Translation” and “the Greek Revision,” were the two sources known to the author of Luke. Thereafter, Bivin follows Lindsey’s conjectured stages of synoptic transmission.

The difficulty with Bivin’s proposal is that he held on to Lindsey’s belief that the original literary contexts of the stories, teaching, and illustrations of the Hebrew biography of Jesus could be reconstructed, even though according to his revised hypothesis there never existed a source in which these literary contexts existed. Bivin also believed that the narrative portions of the Hebrew tradition were composed in a biblicizing style (e.g., with Biblical Hebrew vocabulary and vav-consecutive sentences), while direct speech was preserved in a Mishnaic style of Hebrew (e.g., with Mishnaic Hebrew vocabulary and post-biblical Hebrew grammatical features). This mixed Hebrew style is characteristic of literary sources composed in the late Second Temple period, such as the account of King Yannai preserved in b. Kid. 66a.[6] But how could an oral tradition preserve these kinds of literary (i.e., written) features?

When it came to his attention that he was proposing to reconstruct a source—the Hebrew biography of Jesus—which, according to his revision of Lindsey’s hypothesis, never existed, Bivin retracted his suggested revision and returned to Lindsey’s conjectured stages of synoptic transmission (Hebrew Life of Yeshua → Greek Translation → Anthology → First Reconstruction → Luke → Mark → Matthew).[7] Bivin’s return to Lindsey’s hypothesis was an improvement, but it left the reason for the discomposure of Jesus’ biography unresolved.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

Be sure to check out these recent JP articles:

- Like Every Sparrow Falling: The Symbolism of Sparrows in a Saying of JesusThe multivalent image of the sparrow in ancient Jewish thought made it a useful vehicle for conveying messages about human and divine relationships.

- Better Than the Day of Birth: Reflecting on David Flusser’s Interpretation of the Love Commandment on the 25th Anniversary of His PassingI regard the twenty-fifth anniversary of David Flusser’s passing not solely as a day of loss, but also as the day that gave him to the world.

- 25 Years Since David Flusser’s PassingProfessor Serge Ruzer shares his recollections of Israeli scholar David Flusser on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his death.

- The Discomposure of Jesus’ Biography (Reboot): A Modification to Lindsey’s Conjectured Stages of Synoptic TransmissionHow did the Hebrew biography of Jesus disintegrate into the isolated pericopae that make up the Synoptic Gospels?

- Was the Hemorrhaging Woman Jesus Healed Named Rebekah?Is it possible to retrieve the name of the woman who touched Jesus’ tzitzit?

- Did Jesus Raise Jairus’ Daughter from the Dead?Should readers give more weight to the bystanders’ impressions or to the words Jesus said?

- [1] Bivin (“The Discomposure of Jesus’ Biography,” 33) noted that Brad H. Young had “entertained the suggestion that the rearrangement of Gospel narratives reflects the Gospel lectionary readings in the early church (Jesus and His Jewish Parables: Rediscovering the Roots of Jesus' Teaching [Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989], p. 145).” Cf. Robert L. Lindsey, “Unlocking the Synoptic Problem: Four Keys for Better Understanding Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective 49 (1995): 10-17, 38 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2739/]. ↩

- [2] In twelve years of collaborating on The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction Bivin and Tilton only identified one possible instance of Anth.’s verbal redaction of the Greek Translation of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua. That instance, in Sign-Seeking Generation (L34-35), is an explanatory note, which, in view of the foregoing discussion, is better attributed to the Greek translator, who wanted to make a cryptic remark more decipherable to his Greek-speaking audience. ↩

- [3] See David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “LOY Excursus: The Dates of the Synoptic Gospels,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2020) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/20163/]. ↩

- [4] See David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “‘Yeshua and Levi the Toll Collector’ complex,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2015) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/16336/]. ↩

- [5] See David N. Bivin, “The Discomposure of Jesus’ Biography,” Jerusalem Perspective 53 (1997): 28-33. Bivin (“The Discomposure of Jesus’ Biography,” 28) noted that “the English word ‘discompose’ has two meanings: ‘to destroy the composure or serenity of,’ and ‘to disturb the order of.’ In this article ‘discompose’ is used in its second sense.” ↩

- [6] See David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “Introduction to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction Addendum: Linguistic Features of the Baraita in b. Kid. 66a,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2015) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/14391/]. ↩

- [7] Bivin’s retraction explains why his article, “The Discomposure of Jesus’ Biography,” does not appear on the Jerusalem Perspective site. ↩