How to cite this article: Robert L. Lindsey, “Unlocking the Synoptic Problem: Four Keys for Better Understanding Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective 49 (1995): 10-17, 38 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2739/].

Over several decades of laboring in the Greek texts of the Synoptic Gospels, I have come to recognize four keys for gaining a correct perspective of Jesus. These four keys, when applied properly to the Synoptic Gospels, help significantly in bringing Jesus and his teachings into focus.

Hebrew Beneath the Greek

The first key is command of the biblical languages. Note my use of the plural—“languages.” Knowledge of only Greek is not sufficient for studying the Gospels. In 1959 when preparing a Hebrew translation of the Gospel of Mark,[23] I discovered that much of Mark’s text could be translated readily into Hebrew without changing the word order. This attracted my attention since Greek is a language whose meaning is conveyed more through the forms of words than the order of words in a sentence. Hebrew, however, is a language that depends largely on syntax, or the order of words in a sentence, to convey meaning. So, when I saw Greek sentences written with a word order like that of Hebrew,[24] I began asking the question: What has caused Mark’s Greek to assume Hebrew syntax?

The first key is command of the biblical languages. Note my use of the plural—“languages.” Knowledge of only Greek is not sufficient for studying the Gospels. In 1959 when preparing a Hebrew translation of the Gospel of Mark,[23] I discovered that much of Mark’s text could be translated readily into Hebrew without changing the word order. This attracted my attention since Greek is a language whose meaning is conveyed more through the forms of words than the order of words in a sentence. Hebrew, however, is a language that depends largely on syntax, or the order of words in a sentence, to convey meaning. So, when I saw Greek sentences written with a word order like that of Hebrew,[24] I began asking the question: What has caused Mark’s Greek to assume Hebrew syntax?

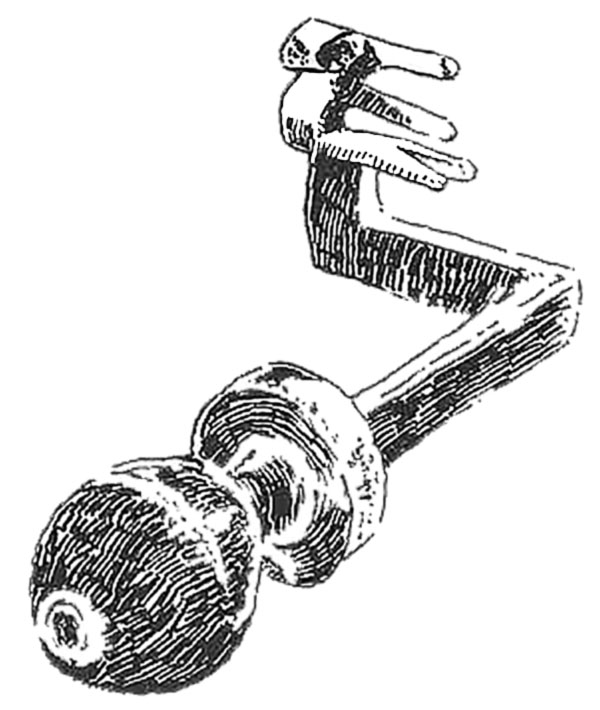

Keys in the time of Jesus were inserted into the keyhole, unlocking the door latch from the inside. Illustration by Helen Twena.

Word order was not the only Hebraism I noticed in Mark and the other two Synoptic Gospels. Hebrew idioms were also plentiful. For example, Jesus frequently talked about the kingdom of heaven. The Greek ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν (hē basileia tōn ouranōn, “the kingdom of the heavens”) is a slavishly literal rendering of the Hebrew expression מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם (mal·CHŪT shā·MA·yim, “kingdom of heavens”). In Hebrew the expression is literally “kingdom of heavens.” The conspicuous plural, “heavens,” is preserved in the Greek τῶν οὐρανῶν (tōn ouranōn, “of the heavens”).[25]

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

- [1] Papias’ work is not extant, but he is quoted by Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History III 39, 16. See Joseph Frankovic, “Pieces to the Synoptic Puzzle: Papias and Luke 1:1-4,” Jerusalem Perspective 40 (Sept./Oct. 1993): 12. ↩

- [2] James Hope Moulton speaks of “Luke’s many imitations of OT Greek” (J. H. Moulton and W. F. Howard, A Grammar of New Testament Greek [3rd ed.; Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1908], 2:18). At English universities a hundred years ago scholars of the classics commonly derided New Testament scholars as students of “Holy Ghost” Greek rather than the bona fide Greek of Plato and Aristotle. ↩

- [3] Such well-known expressions as בָּשָׂר וָדָם (bāsār vādām, "flesh and blood") and מַלְכוּת שָׁמַיִם (malchūt shāmayim, "kingdom of heavens") are not found in the Hebrew Scriptures. ↩

- [4] New Testament scholarship is so inculcated with the supposition that a first-century Jew living in Israel could not have spoken Hebrew as a common, daily language that some translations render τῇ Ἑβραΐδι διαλέκτῳ (tē Hebraidi dialektō, "in the Hebrew dialect"), which appears in Acts 21:40, Acts 22:2 and Acts 26:14, as “in Aramaic.” See Jehoshua M. Grintz, “Hebrew as the Spoken and Written Language in the Last Days of the Second Temple,” Journal of Biblical Literature 79 (1960): 32-47; Shmuel Safrai, “Spoken Languages in the Time of Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective 30 (Jan./Feb. 1991): 3-8, 13; Safrai, “Literary Languages in the Time of Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective 31 (Mar./Apr. 1991): 3-8. ↩

- [5] David Flusser, Jewish Sources in Early Christianity (New York: Adama Books, 1987), 11. Cf. Randall Buth, “Hebrew Poetic Tenses and the Magnificat,” Journal for the Study of the New Testament 21 (1984): 67-83; Buth, “Luke 19:31-34, Mishnaic Hebrew, and Bible Translation: Is κύριοι τοῦ πῶλου Singular?” Journal of Biblical Literature 104 (1985): 680-85; David Bivin, “ The Syndicated Donkey,” Jerusalem Perspective 5 (Feb. 1988): 1-2. ↩

- [6] See Safrai, “Literary Languages in the Time of Jesus”: 5; Brad H. Young, Jesus and His Jewish Parables: Rediscovering the Roots of Jesus’ Teaching (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989), 42; Bivin and Blizzard.Understanding the Difficult Words of Jesus, 7-14, 46-51. ↩

- [7] There are 42 Double Tradition pericopae when counting according to Matthean story order, and 32 when counting by Lukan story order. ↩

- [8] Examples of stories common to Matthew and Luke in the Double Tradition that exhibit low verbal agreement are "The Beatitudes" (Matt. 5:3-10; Luke 6:20-21) and "The Lord’s Prayer" (Matt. 6:9-13; Luke 11:1-4). ↩

- [9] See Lindsey, “An Introduction to Synoptic Studies," subheading, "The Markan Cross-Factor,” Jerusalem Perspective 22 (Sept./Oct. 1989), 10-11. ↩

- [10] Matt. 3:16 (= Mark 1:10); Matt. 13:20 (= Mark 4:16); Matt. 13:21 (= Mark 14:17); Matt. 14:27 (= Mark 6:50); Matt. 21:2 (= Mark 11:2); Matt. 21:3 (= Mark 11:3); Matt. 26:74 (= Mark 14:72). ↩

- [11] See Lindsey, “Paraphrastic Gospels,” footnote 7. ↩

- [12] At these points, Luke’s text is less Semitic than Matthew’s, and it is presumed that Luke is drawing his text from the First Reconstruction, a revision of the earlier Anthology. ↩

- [13] Young, Jesus and His Jewish Parables, 145. ↩

- [14] This notion was put forward by William Wrede in his Das Messiasgeheimnis in den Evangelien (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1901). English translation: The Messianic Secret (trans. J. C. B. Grieg; Cambridge: J. Clarke and Greenwood, SC: Attic Press, 1971). ↩

- [15] Lindsey, “The Messianic Secret, the Parousia, and the Synoptic Problem,” audio cassette (Tulsa, OK: HaKesher, 1990). ↩

- [16] Two such lists of aphorisms appear in Luke 8:16-18 and Luke 9:23-27. For the aphorisms’ parallels embedded in longer contexts, cf. Luke 11:33; Luke 12:2-9 (vss. 2, 9); Luke 14:26-33 (vs. 27); Luke 17:22-37 (vs. 33); and Luke 19:12-27 (vs. 26). ↩

- [17] In his unpublished Ph.D. dissertation (“The Direction of Dependence between Mark and Luke” [Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1995], 34-37), Halvor Ronning has noted 1,163 words involved in the Matthean-Lukan minor agreements. This amounts to 17.4% of the words in Matthew’s Triple Tradition material and 17.9% of Luke’s. Yet there are also over 2,000 words of Mark in Triple Tradition that are not found in the Matthean and Lukan parallels (i.e., Matthean-Lukan agreements against Mark in omission). According to the theory of Markan priority, this would mean that as they copied Mark’s account, Matthew and Luke independently decided to drop these 2,000 words at exactly the same points in their parallels to Mark.

E. P. Sanders and Margaret Davies point out that in the Healing of the Paralytic story (Matt. 9:1-8; Mark 2:1-12; Luke 5:17-26), for instance, counting both positive and negative agreements, Matthew and Luke agree against Mark in twenty-nine Greek words. In one nine-word verse (Mark 2:3, and parallels), Matthew and Luke agree six times against Mark (Studying the Synoptic Gospels [London: SCM Press and Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1989], 71). ↩

- [18] Sanders and Davies state, “The minor agreements between Matthew and Luke against Mark in the triple tradition have always constituted the Achilles’ heel of the two-source hypothesis. There are virtually no triple tradition pericopes without such agreements” (Studying the Synoptic Gospels, 67). Sanders and Davies define “two-source hypothesis” as “belief in the priority of Mark and the existence of ‘Q,’ a symbol for the source which supposedly lies behind the Matthew-Luke double tradition” (65). Cf. E. P. Sanders, “The Overlaps of Mark and Q and the Synoptic Problem,” New Testament Studies 19 (1973): 453-65; Nigel Turner, “The Minor Verbal Agreements of Mt. and Lk. Against Mk.,” Studia Evangelica 73 (1959): 223-34. ↩

- [19] The minor agreements assist in clarifying the heavy dependence of Luke on two non-Markan sources, the editorial tendencies of Mark, the behavior of Matthew when confronted with more than one parallel text, and the nature of the anthological source. See Lindsey, A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark, 17-18. ↩

- [20] See Lindsey, “Jesus’ Twin Parables,” Jerusalem Perspective 41 (Nov./Dec. 1993): 3-6, 12. ↩

- [21] For a list of these stories, see Lindsey, “Jesus’ Twin Parables”: 6. ↩

- [22] The clumping of parables is still visible in Matt. 13. ↩

- [23] For an account of my attempts to translate the Gospel of Mark, see Robert L. Lindsey, A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark (2nd ed.; Jerusalem: Dugith Publishers, 1973), 9-65; Lindsey, Jesus, Rabbi and Lord: A Lifetime’s Search for the Meaning of Jesus’ Words, 25-27. ↩

- [24] Compare, for example, Luke 4:33: “And rebuked him [the demon] Jesus saying….” The sentence begins with “and” followed by the principal verb, and then the subject—typical Hebrew word order. ↩

- [25] Other examples of Hebrew idioms embedded in the Greek text of the Synoptic Gospels are: “bad eye” (Matt. 6:23); “bind” and “loose” (Matt. 16:19); “cast out your name evil” (Luke 6:22); “lay these sayings in your ears” (Luke 9:44); “set his face to go” (Luke 9:51); “give a ring on his hand” (Luke 15:22); and “lifted up his eyes and saw” (Luke 16:23). See David Bivin and Roy B. Blizzard, Understanding the Difficult Words of Jesus (2nd ed.; Shippensburg, PA: Destiny Image Publishers, 1994), 55-65, 103-109, 115-117, 119-126. ↩

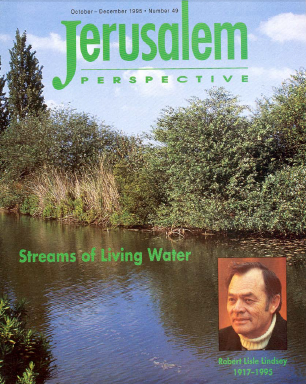

![Robert L. Lindsey [1917-1995]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/28.jpg)