How to cite this article: Shmuel Safrai, “Literary Languages in the Time of Jesus,” Jerusalem Perspective 31 (1991): 3-8 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2563/].

Most Jewish literary activity in the first century C.E. did not take the form of written works, but rather consisted of oral compositions. This was the accepted literary mode of the Pharisees, as well as of Jesus and his early followers. The Sadducees and the Essenes may have written their Bible commentaries and halachah, but the more widely followed Pharisees generally did not. The few written works emanating from Pharisaic circles or groups close to them, such as Megillat Ta‘anit (Scroll of Fasts) or apocryphal works such as 4 Ezra (= 2 Esdras) or the Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch, were certainly a minority.

Teaching, both in large and small groups, was based on oral instruction and not on the reading of texts. Rabbinic sources describe instruction in the synagogue as oral. Synagogal literature such as prayers can be considered part of the literary activity of the time, and this genre likewise began as oral literature.

The documentation of this oral literature took place after the period under discussion here. The first stages of the editing of the Mishnah by Rabbi Yehudah ha-Nasi, and apparently its final redaction as well, took place at the end of the second and the beginning of the third century C.E. In the first century C.E., the literary activity of the sages was oral and their literary creations were transmitted orally. Although it is probable that students sometimes took notes when their teacher taught (rabbinic sources only give evidence of this practice beginning in the second century C.E.), it is necessary to stress that the majority of teaching and study was oral.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

- [1] See M (= Mishnah) Ta’anit 2:8; JT (= Jerusalem Talmud) Ta’anit 66a; BT (= Babylonian Talmud) Ta’anit 17b. ↩

- [2] In the opening section of The Jewish War (1:3), Josephus relates that he originally wrote his work “in the tongue of my fathers” and sent it to the Jews living in the eastern lands. Although many scholars claim that the work was originally written in Aramaic, there is no proof that this was the case, and Josephus may have written in Hebrew. See J. M. Grintz, “Hebrew as the Spoken and Written Language in the Last Days of the Second Temple,” JBL 79 (1960): 42-45. ↩

- [3] M Eduyot 8:4. ↩

- [4] M Avot 1:13; 2:6. ↩

- [5] For example, M Peah 2:2; M Bava Kamma 1:2. For a list of the early halachot in the Mishnah written in a Hebrew similar to that of biblical Hebrew, see J. N. Epstein, מבוא לנוסח המשנה (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1948), 2:1129-1133. For other early tannaic sayings, see BT Kiddushin 66a; Sifre Numbers 22, to 6:2 (ed. Horovitz, p. 26). ↩

- [6] Such technical terms as the following are Hebrew and not Aramaic: אָמְרָה תּוֹרָה (’ām·RĀH tō·RĀH, "the Torah states"), בִּנְיָן אָב (bin·YĀN ’āv, "general law derived from special cases"), הֲרֵינִי דָּן (ha·RĒ·ni dān, "thus I conclude"), לְפִי דַרְכֵּנוּ לָמַדְנוּ (le·fi dar·KĒ·nū lā·MAD·nū, "in the process of our study we have learned"), לְשׁוֹן מְרֻבֶּה וּלְשׁוֹן מוּעָט (le·SHŌN me·ru·BEH ūl·SHŌN mū·‘ĀṬ, "all-inclusive and non-inclusive language"), דָּבָר הַלָּמֵד מֵעִנְיָנוֹ (dā·VĀR ha·lā·MĒD mē·‘in·yā·NŌ, "a matter learned from its context"), תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר (tal·MŪD lō·MAR, "learn the thing from what is written," i.e., "the answer to your question is found in the words of Scripture"). See the discussion and list of homiletical terms used by Tannaim and Amoraim in Wilhelm Bacher, Die Älteste Terminologie der Jüdischen Schriftauslegung (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1899); idem, Die Exegetische Terminologie der Jüdischen Traditionsliteratur (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1905), I-II. ↩

- [7] Two examples from amoraic literature in which the context is Aramaic, but the halachah and midrash are Hebrew: a) Genesis Rabbah 7:1-2 (ed. Albeck, pp. 50-52) and its parallels relate two stories regarding the teachings of Ya’akov of Kefar Niburaia in Tyre. The sage apparently was close to the Judeo-Christians. His halachic teachings in Tyre were not in accordance with normative halachah. The story is written for the most part in Aramaic, but the halachah and midrash in it are in Hebrew. b) In JT Shabbat 7d there is a discussion about teaching girls Greek. The story is in Aramaic, but the halachic reference is in Hebrew. ↩

- [8] See M Eruvin 3:9. ↩

- [9] See the prayer of Rabbi Nehuniah ben ha-Kanah in M Berachot 4:2. See also the many prayers listed in JT Berachot 7d and BT Berachot 16b-17b. ↩

- [10] For example, BT Sotah 22a. ↩

- [11] The very few words in rabbinic prayers which appear to be Greek or Aramaic are actually Hebrew or do not belong to the original text. BT Yoma 53b relates part of the High Priest’s prayer on the Day of Atonement as being in Aramaic: “May there not depart a ruler from the house of Judah.” This apparently was not part of the High Priest’s prayer. It is only one of the versions and does not appear in the parallel in JT Yoma 42c. In reality, this Aramaic prayer has been taken from Targum Onkelos on Genesis 49:10 and certainly does not reflect the reality of the end of the Second Temple period. Late prayers from the geonic period do have Aramaic words and some, like the kaddish, a prayer recited as part of the daily synagogue liturgy and by mourners at public services after the death of a close relative, were even written in Aramaic. The piyutim, late poetry of the sixth-seventh centuries C.E.ff. which expand and embellish the prayers, contain some Greek words. ↩

- [12] BT Shabbat 12b; BT Sotah 33a. ↩

- [13] One such attempt is found in Gustaf Dalman, Die Worte Jesu, 2nd ed. (Leipzig: Hinrichs, 1930). ↩

- [14] See BT Bava Kamma 60b or BT Sotah 40a. ↩

- [15] For example, Leviticus Rabbah 3:1 (ed. Margulies, pp. 56-57). Such proverbs are often prefaced with דאמרי אינשי (as people are accustomed to say) or במתלא אמרין (in a proverb they state). ↩

- [16] 2 Maccabees 1:1, 7, 10; Acts 28:21; BT Sanhedrin 12a. ↩

- [17] For example: “And the men of Jerusalem used to write: ‘From great Jerusalem to small Alexandria’” (JT Hagigah 77d). ↩

- [18] First published by A. E. Cowley, JEA 2 (1915): 209-213. See also Corpus Papyrorum Judaicarum, (ed. V. A. Tcherikover; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 1:101-102. ↩

- [19] M Ketubot 4:4; Semahot 14:7. See The Jewish People in the First Century (eds. S. Safrai and M. Stern; Assen-Amsterdam, 1976), 2:773-776. ↩

- [20] BT Sanhedrin 11a; Semahot 8:7; BT Sanhedrin 68a. ↩

- [21] See E. Feldman, “The Rabbinic Lament,” JQR 63 (1972-3): 51-75. ↩

- [22] BT Moed Katan 25b; BT Avodah Zarah 34b; JT Moed Katan 81c; BT Ketubot 104a, et al. ↩

- [23] For example, BT Ketubot 77b. ↩

- [24] T (= Tosefta) Sotah 13:5 and parallels; cf. Antiquities 13:282. See S. Safrai, “Zechariah’s Prestigious Task,” JerPers 2.6 (1989): 1, 4. ↩

- [25] T Sotah 13:6. The utterance that the priest heard was, “Abolished is the abomination that the hater wished to bring into the sanctuary.” ↩

- [26] BT Sotah 48b; BT Sanhedrin 11a. ↩

- [27] Even in later rabbinic sources, however, a number of heavenly voices were recorded in Aramaic (JT Peah 15d; BT Bava Batra 3b, et al.). ↩

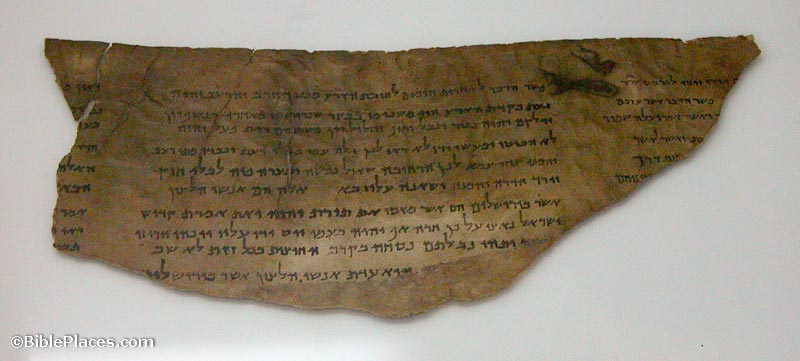

- [28] M Gittin 9:3. See the bill of divorce that was discovered at Murabba’at and published in Discoveries in the Judaean Desert, eds. P. Benoit, J.T. Milik and R. de Vaux (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), 2:104-109. ↩

- [29] M Ketubot 4:7-12; T Ketubot 4:2. ↩

- [30] The fragments of Ben Sira found at Masada were written in the first century B.C.E. See Y. Yadin, The Ben Sira Scroll from Masada (Jerusalem, 1965), especially note 11 in Yadin’s introduction. All of the Hebrew fragments from the Cairo Genizah were published in ספר בן-סירא השלם (Sefer Ben-Sira Hashalem), ed. M. Z. Segal (Jerusalem, 1958). ↩

- [31] See Segal’s "Introduction," 37-38. ↩

- [32] A Genesis Apocryphon, eds. N. Avigad and Y. Yadin (Jerusalem, 1956). ↩

- [33] This is the view of C. Rabin. See his “Hebrew and Aramaic in the First Century,” in The Jewish People in the First Century, op. cit., p. 1036. ↩

- [34] For a survey of the linguistic picture in first-century Israel, see C. Rabin, op. cit., pp. 1007-1039. See also H. Birkeland, The Language of Jesus (Oslo, 1954). Still beneficial is the extended introduction (המבוא הגדול, Prolegomenon) of Eliezer Ben Yehuda to his 17-volume Hebrew dictionary,מלון הלשון העברית [English title: A Complete Dictionary of Ancient and Modern Hebrew] (Jerusalem: Thomas Yoseloff, 1910-1959). For more modern studies, see Y. E. Kutscher, in “The Language of the Sages,” H. Yalon Jubilee Volume (Jerusalem, 1963), 246-280 (= קובץ מאמרים בלשון חז″ל, ed. M. Bar-Asher [Jerusalem, 1972], 1-35.) See also M. H. Segal, “Mishnaic Hebrew and Its Relation to Biblical Hebrew and to Aramaic,” JQR, O.S. 20 (1908): 647-737; and the introduction to Segal’s book, A Grammar of Mishnaic Hebrew (Oxford: Clarendon, 1927), 1-20. ↩

![Shmuel Safrai [1919-2003]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/20.jpg)