How to cite this article:

David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “Tumultuous Times,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2022) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/24400/].

Matt. 24:7-8; Mark 13:8; Luke 21:10-11[1]

Updated: 4 December 2025

וַיֹּאמֶר לָהֶם יָקוּם גּוֹי בְּגוֹי וּמַמְלָכָה בְּמַמְלָכָה וְיִהְיֶה רָעָב וְדֶבֶר וּפַחַד וְרַעַשׁ וּמִן הַשָּׁמַיִם סִימָנִים גְּדוֹלִים [תְּחִילַּת חֲבָלִים אֵלּוּ]

“One people group will rise up against another,” Yeshua replied. “And one empire will clash with another. There will be famine, disease, panic and earthquakes. And from the sky unmistakably bad portents will appear. [From these you will know the birthing pains are beginning.][2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Tumultuous Times click on the link below:

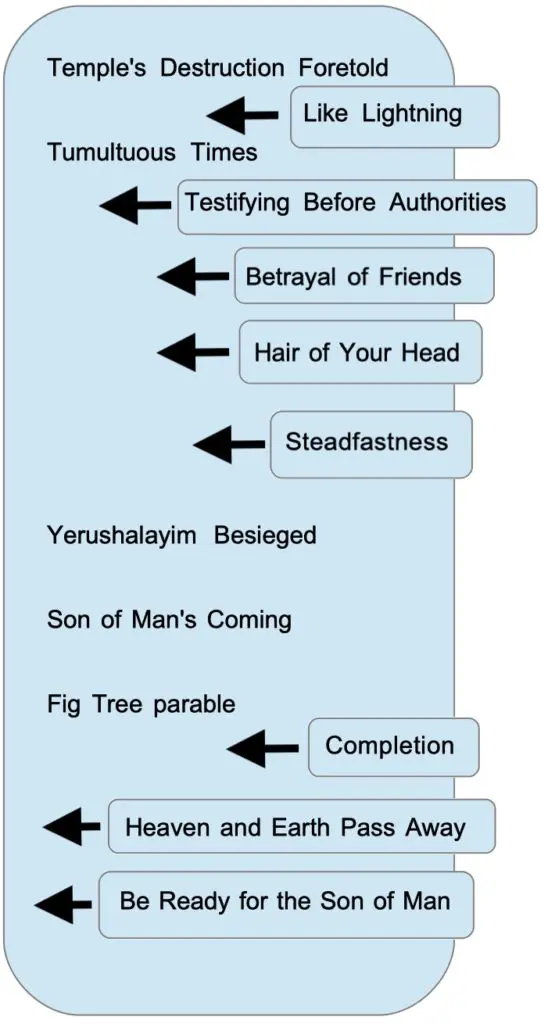

| “Destruction and Redemption” complex |

| Temple’s Destruction Foretold ・ Tumultuous Times ・ Yerushalayim Besieged ・ Son of Man’s Coming ・ Fig Tree parable |

Story Placement

According to our reconstruction of the “Destruction and Redemption” complex, Tumultuous Times forms the beginning of Jesus’ response to the question “What is the sign that these things [i.e., the razing of the Temple] are about to take place?” which the audience put to Jesus at the end of Temple’s Destruction Foretold. Between the audience’s question (Luke 21:7) and the opening of Jesus’ response (Luke 21:10) the First Reconstructor inserted warnings about messianic pretenders who will opportunistically capitalize on the people’s hopes and fears as the Roman legions close in on the land of Israel (Like Lightning; Luke 21:8-9).

That Like Lightning is a secondary insertion can be seen from the fact that this pericope has a doublet in Luke 17:22-25, which comes from a block of material copied from the Anthology (Anth.).[3] The phrase τότε ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς (“then he was saying to them”), which opens Tumultuous Times (L1; Luke 21:10), provides another clue that the contents of Luke 21:8-9 were inserted between the question in Luke 21:7 and the beginning of Jesus’ reply in Luke 21:10, for otherwise this introductory phrase is entirely superfluous in the middle of continuous direct speech. A third clue that Like Lightning is a secondary intrusion in Luke 21 is the fact that in Tumultuous Times Jesus gives a simple and direct answer to the audience’s question about a sign by enumerating several catastrophic events that will portend that the Temple’s destruction is at hand.[4]

The list of portents in Luke 21:10-11 (wars, earthquakes, famines, pestilences, terrors, signs in the heavens) is similar to a list of calamities in Deut. 32 (including, inter alia, famine, plagues, drought, war) that culminates in exile that will come upon Israel as punishment for violating the covenant. The calamities mentioned in Tumultuous Times are especially close to a series of punishments (sword, famine, pestilence) that the prophet Jeremiah warned would culminate in the destruction of the First Temple (Jer. 21:9; 24:10; 27:8, 13; 29:17, 18; 32:24, 36; 34:17; 38:2). The list of portents in Tumultuous Times also resembles a catalog of punishments (various kinds of famine, pestilence, sword, vicious beasts)[5] that culminates in exile known from rabbinic sources (m. Avot 5:8-9). Other portents Jesus mentions in Tumultuous Times (terrors, signs in the heavens) resemble reports in Josephus’ writings and rabbinic literature about strange and ominous happenings in the Temple in the years preceding its destruction.[6]

Because the portents described in Tumultuous Times so closely resemble standard lists of punishments for persistent disobedience, it does not appear necessary to interpret these calamities as signs of the eschaton.[7] For this reason we do not concur with those scholars who seek to join the signs mentioned in Luke 21:10-11 portending the destruction of the Temple with the signs mentioned in Luke 21:25-26 premonitory of the eschatological appearance of the Son of Man.[8] Indeed, Lindsey’s hypothesis—despite Lindsey’s literary reconstruction[9] —offers a strong reason against our doing so. Whereas Tumultuous Times lacks a Lukan doublet outside Luke 21 or a Matthean parallel outside Matt. 24, all the pericopae we regard as secondary First Reconstruction (FR) insertions into Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption do have such Lukan and/or Matthean parallels. None of the pericopae we regard as being original components of Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption have doublets outside the discourses in Luke 21 ∥ Mark 13 ∥ Matt. 24. Lindsey’s hypothesis can account for these facts by supposing that the First Reconstructor retained the position these pericopae occupied in Anth. while interspersing his supplementary materials between them. Therefore, when the author of Luke chose FR’s version of Jesus’ discourse in preference to Anth.’s, he had no occasion to include the alternate Anth. versions of these pericopae elsewhere in his Gospel.

It is likely that the author of Luke preferred FR’s expanded version of the prophecy, which not only related to the experience of the Jewish people, but, in foretelling the trials to be endured by Jesus’ followers, also seemed to address the experiences of the non-Jewish believers for whom Luke’s Gospel was intended.

For an overview of the “Destruction and Redemption” complex click here.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

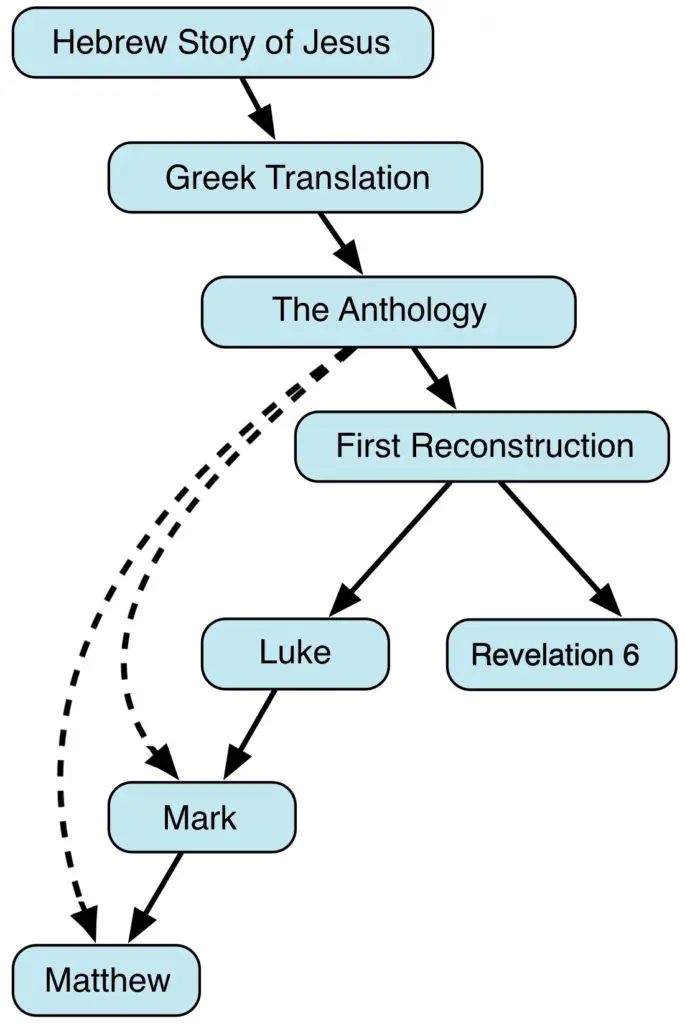

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

Our discussion concerning the placement of Tumultuous Times has already indicated that we believe the author of Luke copied Tumultuous Times from the First Reconstruction (FR).[10] The author of Mark merged Tumultuous Times with Like Lightning, the pericope that precedes it, and in so doing he abbreviated the list of portents, eliminating pestilence, terrors and signs from heaven. The author of Matthew based his version of Tumultuous Times on Mark’s, making a few changes here and there, some of which may have been informed by his acquaintance with the version in Anth. That the author of Matthew did not see fit to restore from Anth. any of the portents the author of Mark omitted may be related to his emphasis on “the sign of the Son of Man” (Matt. 24:3, 30). Elaboration of signs of the Temple’s destruction would have distracted readers from his focus on this all-important eschatological sign.

Scholars have observed the striking similarity between the first six seals described in Revelation 6 and the portents mentioned in Luke’s version of Tumultuous Times.[11] Revelation’s vision of the seals features the four horsemen of the apocalypse who take turns riding over the earth at the breaking of the first four seals.[12] R. H. Charles[13] identified the six seals as representing 1) war (white horse), 2) international strife (red horse), 3) famine (black horse), 4) pestilence (pale horse), 5) persecutions, 6) earthquake and astronomical signs. The table below places the order of the seals and the order of portents in Luke’s version of Tumultuous Times side by side:

| Six Seals (Rev. 6) | Tumultuous Times (Luke) |

| War (white horse, rider with bow) |

people rising up against people |

| International Strife (red horse, rider with sword) |

kingdom (rising up) against kingdom |

| earthquakes | |

| Famine (black horse, rider with scales) |

famines |

| Pestilence (pale horse, rider named Death) |

pestilences |

| Persecution | terrors |

| Earthquake and Astronomical Signs | signs from heaven |

Aside from the placement of “earthquake,” the order of the seals in Revelation is almost identical to the portents identified in Luke’s version of Tumultuous Times. The only apparent discrepancy is between the fifth seal, representing persecution, and “terrors” in Luke’s list. However, it is possible that this discrepancy is merely one of appearance rather than of substance, for the revelator may have equated “terrors” with persecution, as we will discuss below. Since in the Markan and Matthean versions of Tumultuous Times the list of portents excludes pestilence, terrors and signs from heaven, it is clearly to Luke’s version of Tumultuous Times that the vision of the seals bears some kind of relationship.

On the other hand, whereas Luke’s version of Tumultuous Times merely states that there will be great signs from heaven, the account of the opening of the sixth seal in Revelation describes what those signs will be:

…and the sun became black as hair sacking material, and the full moon became like blood, and the stars of heaven fell to the earth as a fig casts its fruit when shaken by a great wind, and heaven was detached like a scroll being rolled up…. (Rev. 6:12-14)

This account in Revelation is very close to the astronomical portents described in Mark’s (and Matthew’s) version of Son of Man’s Coming:

…the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken. (Mark 13:24-25; cf. Matt. 24:29).

Luke’s version of Son of Man’s Coming merely states that there will be signs in the sun, moon and stars and that the powers of heaven will be shaken (Luke 21:25-26).[14]

One explanation for the similarities of the vision of the signs to Luke in certain respects and to Mark and Matthew in others is that the revelator merged the Lukan version of Tumultuous Times with the Markan or Matthean version of Son of Man’s Coming. R. H. Charles offered a more elegant explanation. He suggested that the revelator drew on a pre-synoptic version of Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption.[15] We think Charles’ solution is more likely to be correct because the vision of the seals contains elements that appear to be more primitive than what appears in Luke’s version of Tumultuous Times and the Markan-Matthean versions of Son of Man’s Coming. With regard to Luke, the revelator’s use of θάνατος (thanatos, “death”) in the sense of “pestilence” appears to be more original than Luke’s use of λοιμός (loimos, “pestilence”) (see below, Comment to L8). With respect to Mark and Matthew, the revelator’s use of similes to describe the astronomical phenomena seems more primitive than the Septuagintalizing language we find in Mark and Matthew. There are additional elements in the vision of the seals that appear to be more primitive than the details in the synoptic versions of Tumultuous Times and Son of Man’s Coming, which we will discuss below or in the commentary to Son of Man’s Coming. These primitive elements in the vision of the seals suggest that the revelator did not merge Luke’s version of Tumultuous Times with the Markan or Matthean version of Son of Man’s Coming, but that he merged the versions of these two pericopae that occurred in a source that was undisturbed by Lukan, Markan and Matthean redaction.

Supposing that the revelator did depend on a pre-synoptic source behind Tumultuous Times, the persecution of Christians represented by the fifth seal indicates which pre-synoptic source the revelator used.[16] As we have discussed elsewhere, Anth.’s version of Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption was addressed to the Jewish people as a whole.[17] For such an audience, the persecutions to be endured by Jesus’ followers would have been out of place. It was the First Reconstructor who introduced the theme of persecution into Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption.[18] Therefore, if the revelator used a pre-synoptic source known to the author of Luke, that source must have been FR.

In the commentary below we will proceed on the hypothesis that Revelation’s vision of the seals bears witness to FR’s version of Tumultuous Times independent of the Synoptic Gospels.

Crucial Issues

- Do the events described in Tumultuous Times depict premonitions of the Temple’s destruction, or are they “the birthing pain of the Messiah” leading up to redemption?

- Did the events Jesus predicted take place? Or was he wrong? Or are they yet to happen?

Comment

L1 τότε ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς (Luke 21:10). In its present context the phrase “then he was saying to them” needlessly interrupts Jesus’ direct speech. The author of Mark clearly regarded this phrase as both intrusive and superfluous, since he eliminated it from his version of Tumultuous Times.[19] Many scholars have recognized that the presence of “then he was saying to them” in Luke 21:10 is a literary seam that reflects a transition between sources.[20] According to their view, τότε ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς (tote elegen avtois, “then he was saying to them”) marks a point at which the author of Luke switched from using Mark 13 to using his non-Markan source.[21] We agree that τότε ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς is a literary seam, but we do not think it was the author of Luke who switched sources. In our view, “then he was saying to them” is FR’s paraphrase of the introduction to Jesus’ reply to the questions “When will these things happen? And what is the sign when these things are about to be done?” (Temple’s Destruction Foretold, L42-45). Between these questions and Jesus’ original reply the First Reconstructor inserted the Like Lightning pericope. Thus, τότε ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς marks the point at which FR returned to the original core of Jesus’ prophecy as it was preserved in Anth.

καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς (GR1). Ordinarily, the author of Luke’s editing of FR was minimal and, consequently, indistinguishable from FR’s redaction of Anth. For this reason most LOY reconstruction documents have only a single Greek Reconstruction (GR) column representing Anth., the presumption being that reconstructing FR is unnecessary because FR’s wording has been replicated in Luke.[22] However, as we noted in the Conjectured Stages of Transmission discussion above, it is possible that in the vision of the seals in Revelation 6 we have an independent witness to FR’s version of Tumultuous Times. This independent witness allows us to distinguish in Tumultuous Times between FR redaction and Lukan editorial activity. In this unusual situation it is useful to have two GR columns (GR1 and GR2) in the reconstruction document for Tumultuous Times. GR1 represents Anth., while GR2 represents FR.

In L1 τότε (tote, “then”) is likely to be redactional, since narrative τότε is un-Hebraic and atypical of Luke’s Gospel.[23] Likewise, the imperfect tense of ἔλεγεν (elegen, “he was saying”) is probably redactional, since aorist verbs are more typical of the translation-Greek style we expect from Anth.[24] The author of Luke probably adopted both of these redactional features from FR. Anth.’s text is likely to have had a more Hebraic phrase such as καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς (kai eipen avtois, “and he said to them”).

L2 ἐγερθήσεται γὰρ (Mark 13:8). By eliminating an equivalent to “then he was saying to them” in L1 and by inserting γάρ (gar, “for”) in L2 the author of Mark succeeded in fusing two originally independent pericopae: Like Lightning and Tumultuous Times. This is an improvement upon the awkward break in Jesus’ discourse caused by τότε ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς in Luke 21:10 (L1), and as such Mark’s wording should be recognized as secondary. The author of Matthew accepted Mark’s stylistically better wording which erases the break in Jesus’ speech. Anth.’s text, like FR and Luke, probably simply read ἐγερθήσεται (egerthēsetai, “he/she/it will be raised up”) in L2.

יָקוּם (HR). On reconstructing ἐγείρειν (egeirein, “to rise”) with קָם (qām, “arise”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L15.

L3 ἔθνος ἐπὶ ἔθνος (Luke 21:10). Although according to Codex Vaticanus, which serves as the base text for our reconstruction, there appears to be a Lukan-Matthean minor agreement in L3 to write ἐπί (epi, “upon”) instead of the contracted form ἐπ᾽ (ep, “upon”), text critics regard ἐπ᾽ as the original reading in Luke 21:10 (L3).

ἔθνος ἐπὶ ἔθνος (GR1). Since it is unlikely that the author of Matthew would have replaced the grammatically correct ἐπ᾿ ἔθνος with ἐπὶ ἔθνος without cause, we suspect the author of Matthew wrote ἐπί in place of Mark’s ἐπ᾿ because he saw ἐπί in Anth.[25]

גּוֹי בְּגוֹי (HR). On reconstructing ἔθνος (ethnos, “people group”) with גּוֹי (gōy, “people group”), see Conduct on the Road, Comment to L52.

Although it is more common for us to reconstruct ἐπί (epi, “upon”) with עַל (‘al, “upon”), when קָם (qām, “stand,” “arise”) is used in the sense of “rise up against” the accompanying preposition is often -בְּ (be–), for instance:

לֹא יָקוּם עֵד אֶחָד בְּאִישׁ

A single witness must not rise up against a man…. (Deut. 19:15)

כִּי יָקוּם עֵד חָמָס בְּאִישׁ

If a malicious witness rises up against a man…. (Deut. 19:16)

כִּי קָמוּ בִי עֵדֵי שֶׁקֶר

For false witnesses have risen up against me. (Ps. 27:12)

Sometimes in these cases the LXX translators rendered the preposition -בְּ as ἐπί, for instance:

בַּת קָמָה בְאִמָּהּ כַּלָּה בַּחֲמֹתָהּ אֹיְבֵי אִישׁ אַנְשֵׁי בֵיתוֹ

…a daughter rises up against her mother, a daughter-in-law [rises up] against her mother-in-law, a man’s enemies are the people of his household. (Mic. 7:6)

θυγάτηρ ἐπαναστήσεται ἐπὶ τὴν μητέρα αὐτῆς, νύμφη ἐπὶ τὴν πενθερὰν αὐτῆς, ἐχθροὶ ἀνδρὸς πάντες οἱ ἄνδρες οἱ ἐν τῷ οἴκῳ αὐτοῦ

…a daughter stands up against her mother, a daughter-in-law [stands up] against her mother-in-law, a man’s enemies are all the men who are in his house. (Mic. 7:6)

In prophetic literature tranquility between the Gentile nations is a sign of God’s blessing toward Israel. Thus we read:

וְכִתְּתוּ חַרְבוֹתָם לְאִתִּים וַחֲנִיתוֹתֵיהֶם לְמַזְמֵרוֹת לֹא יִשָּׂא גוֹי אֶל גּוֹי חֶרֶב וְלֹא יִלְמְדוּ עוֹד מִלְחָמָה

…and they will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Gentile will not lift up sword against Gentile, and they will not study war anymore. (Isa. 2:4; cf. Mic. 4:3)

On the other hand, when God’s blessing is revoked because of Israel’s disobedience, strife breaks out among the Gentiles:

וְיָמִים רַבִּים לְיִשְׂרָאֵל לְלֹא אֱלֹהֵי אֱמֶת וּלְלֹא כֹּהֵן מוֹרֶה וּלְלֹא תוֹרָה׃ וַיָּשָׁב בַּצַּר לוֹ עַל יי אֱלֹהֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיְבַקְשֻׁהוּ וַיִּמָּצֵא לָהֶם׃ וּבָעִתִּים הָהֵם אֵין שָׁלוֹם לַיּוֹצֵא וְלַבָּא כִּי מְהוּמֹת רַבּוֹת עַל כָּל יוֹשְׁבֵי הָאֲרָצוֹת׃ וְכֻתְּתוּ גוֹי בְּגוֹי וְעִיר בְּעִיר כִּי אֱלֹהִים הֲמָמָם בְּכָל צָרָה׃

Israel had many days without the true God and without a teaching priest and without Torah. But when Israel had distress it returned to the LORD the God of Israel, and they sought him, and he was found for them. But in those times [of disobedience] there was no peace for the one going out or the one entering, for there were great disturbances upon the inhabitants of the lands. And they were beaten, Gentile against Gentile and city against city, for God troubled them with every distress. (2 Chr. 15:3-6)

Instead of the Gentiles beating their weapons into implements of peace, the Gentiles beat one another into mutual destruction. Because international strife was interpreted as a sign of divine displeasure, it is featured in apocalyptic descriptions of the eschaton (cf., e.g., 4QAramaic Apocalypse [4Q246] II, 3; 4 Ezra 13:31).[26] But, as the example from 2 Chronicles shows—and as practical experience taught—international strife was not an intrinsically eschatological sign. From the prophetic perspective, enmity between the Gentiles was liable to break out anytime Israel acted in disobedience to God.

L4 καὶ βασιλεία ἐπὶ βασιλείαν (GR1-2). Since the Lukan, Markan and Matthean versions of Tumultuous Times are in agreement in L4, and since καὶ βασιλεία ἐπὶ βασιλείαν (kai basileia epi basileian, “and kingdom against kingdom”) reverts easily to Hebrew (see below), no further comment is required for GR.

וּמַמְלָכָה בְּמַמְלָכָה (HR). In most LOY segments we reconstruct the noun βασιλεία (basileia, “kingdom”) with מַלְכוּת (malchūt, “reign,” “kingdom”),[27] but occasionally מַמְלָכָה (mamlāchāh, “kingdom”) seems preferable, as in Yeshua’s Testing, L42. Here, too, מַמְלָכָה seems preferable, since we encounter the phrase מַמְלָכָה בְּמַמְלָכָה (mamlāchāh bemamlāchāh, “kingdom against kingdom”) in Isa. 19:2, while the phrase מַלְכוּת בְּמַלְכוּת (malchūt bemalchūt, “kingdom against kingdom”) is unattested in Hebrew sources. Many scholars suppose that Jesus alluded to Isa. 19:2 in Tumultuous Times,[28] but we remain somewhat skeptical, since there is no clear reason why such an allusion would be desirable.[29]

Whether or not Jesus’ predictions were fulfilled in the years leading up to the destruction of the Second Temple is not a useful criterion for determining whether or not Jesus actually made such predictions. For if it be determined that these events did take place, it could always be claimed that these predictions were projected back onto Jesus by the transmitters of the Gospel tradition.[30] On the other hand, were it determined that these events did not take place, this is no proof that Jesus did not mistakenly believe they would happen. Likewise, whether or not the events foreseen in Tumultuous Times have already taken place cannot help us to determine whether these signs were intended to herald the destruction of the Temple (as the context of Tumultuous Times in all three Synoptic Gospels clearly indicates) or whether these signs were originally intended to herald the eschatological coming of the Son of Man (as some scholars have suggested). For if it be determined that the events foreseen in Tumultuous Times have not taken place, we must still reckon with the possibility that Jesus, who had not the advantage of our historical hindsight, was mistaken. As it happens, however, the signs Jesus described in Tumultuous Times are such that they could characterize almost any period of human history.[31] It is therefore not surprising to find in the historical record events that match the description of each of the signs enumerated in Tumultuous Times.

With respect to international political disturbances, we may point to the hostilities between Herod Antipas and his erstwhile father-in-law Aretas IV in the 30s C.E., the Roman invasion of Britain and the Parthian threat to Adiabene in the 40s C.E., the Roman-Parthian war of the late 50s and early 60s C.E., and the Roman civil war in 68-69 C.E. Such political unrest near and far, within the Roman Empire and beyond it, could well have been interpreted as signs of the withdrawal of God’s blessing and protection of Israel.

Examples of Political Disturbances Between

the Time of Jesus’ Prophecy and 70 C.E.

| Date | Description | Source |

| 35 C.E. | Armenia: Dispute over royal succession between the Roman-backed Mithradates and the Parthian-backed Orodes. Parthia defeated, Artabanus III ousted from Parthian throne. | Tacitus, Ann. 6:32-36 |

| 35-36 C.E. | Parthia: Ousted king Artabanus III vies with Tiridates III, backed by Vitellius, the Roman governor of Syria, for the rule of Parthia. Artabanus victorious. | Jos., Ant. 18:96-105; Tacitus, Ann. 6:37, 41-44; Dio Cassius, Roman History 59:27 §3 |

| 36 C.E. | Perea (Transjordan): Aretas IV of Nabatea invades the territory of Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee and Perea. Vitellius, governor of Syria, assists Antipas. | Jos., Ant. 18:113-115, 120-125 |

| 36 C.E. | Cilicia (Asia Minor): Revolt of the Cietae tribe against Archelaus of Cilicia, a client king of the Roman Empire. The revolt was suppressed by Roman forces sent by Vitellius. | Tacitus, Ann. 6:41 |

| 35/36-43 C.E. | Seleucia in Mesopotamia: The city of Seleucia rebels against the Parthian Empire. Massacre of Jews by the Greek and Aramean population of Seleucia takes place some years into the rebellion. | Jos., Ant. 18:371-379; Tacitus, Ann. 6:42; 11:8f. |

| 38 C.E. | Parthia: Dispute of royal succession between Vardanes and Gotarzes, two sons of Artabanus III. Vardanes has the upper hand until his death in 45 C.E. | Tacitus, Ann. 11:8, 10 |

| 38 C.E. | Armenia: The Roman-backed Mithradates claims the Armenian throne. | Tacitus, Ann. 11:9 |

| 41-42 C.E. | Mauretania (North Africa): Revolt against the Roman Empire | Pliny, Nat. 5:1 §11, 14, 16; Dio Cassius, Roman History 60:9 |

| 43 C.E. | Britain: Roman invasion and conquest of Britain begins under Claudius. | Suetonius, Claud. 17:1-2 |

| 49 C.E. | Parthia: Dispute of royal succession between Gotarzes II and the Roman-backed Meherdates. Gotarzes prevails. | Tacitus, Ann. 12:10-14 |

| 58-63 C.E. | Armenia: Roman-Parthian War for the control of Armenia | Tacitus, Ann. 12:44-51; Suetonius, Nero 39:1 |

| 60-61 C.E. | Britain: Revolt against the Roman Empire | Suetonius, Nero 39:1 |

| 67-68 C.E. | Gaul: Revolt against Nero led by the Roman prefect Vindex | Jos., J.W. 4:440; Suetonius, Galb. 9:2; Dio Cassius, Roman History 63:22 |

| 68-69 C.E. | Rome: Roman Civil War | Jos., J.W. 4:491-502, 545-549, 585-607, 616-621, 630-658 |

L5 σεισμοί τε μεγάλοι (Luke 21:11). We have several reasons for supposing that the author of Luke moved “earthquakes” from its original penultimate position to the top of the list of natural disasters. First, as we noted in the Story Placement section above, the disasters mentioned in Tumultuous Times appear to be based, at least in part, on a pattern that is frequently repeated in the book of Jeremiah, according to which disobedient Israel will be punished with the sword, famine and pestilence.[32] Once in Jeremiah this sequence is followed by a fourth item, זְוָעָה (zevā‘āh; Jer. 29:18; cf. Jer. 34:17), according to the written text.[33] In Biblical Hebrew the term זְוָעָה meant “terror” or “fear-inspiring object,” but in Mishnaic Hebrew זְוָעָה came to mean “earthquake.”[34] For Hebrew-speaking Jews of the first century the meaning of זְוָעָה in Jer. 29:18 likely seemed ambiguous. Some readers would have understood ורדפתי אחריהם בחרב ברעב ובדבר ונתתים לזועה, the written text of Jer. 29:18, as “And I will pursue after them with the sword, with famine and with pestilence, and I will make them a [or, I will give them over to] terror,” while others might have understood the written text as “And I will pursue after them with the sword, with famine and with pestilence, and I will give them over to earthquake.”[35] Midrashists may even have combined the two interpretations: “I will pursue after them with the sword, with famine and with pestilence; I will give them over to terror and to earthquake.” Such a midrashic interpretation of Jer. 29:18 yields the sequence sword→ famine→ pestilence→ terror→ earthquake. Luke’s sequence in Tumultuous Times is wars→ earthquakes→ famines→ pestilences→ terrors. If Tumultuous Times was based on a midrashic understanding of Jer. 29:18, then we must suspect that the author of Luke changed the sequence of disasters.

Corroborating our suspicion that the author of Luke moved “earthquakes” from its original position is the sequence of disasters given in the vision of the seals in Rev. 6. As we saw in the Conjectured Stages of Transmission discussion above, there is reason to believe that the vision in Rev. 6 bears witness to FR’s version of Tumultuous Times independent of Luke. In Rev. 6 the order of catastrophes is wars→ famine→ pestilence→ persecution→ earthquake→ astronomical phenomena, whereas Luke’s sequence is wars→ earthquakes→ famines→ pestilences→ terrors→ signs from heaven. Charles thought that the author of Revelation was responsible for moving “earthquake” from its original position,[36] but since with respect to the placement of “earthquake” the sequence in Rev. 6 agrees with the conjectured midrashic interpretation of Jer. 29:18, it is more likely that the author of Luke moved “earthquake” from its position in FR.

Matthew’s sequence of catastrophes in Tumultuous Times may also corroborate our suspicion that the author of Luke moved “earthquake” from its original position. The author of Matthew must have had some reason for changing Mark’s order of earthquakes→ famines to the order of famines→ earthquakes. If the author of Matthew could see that the order in Anth. was wars→ famine→ pestilence→ terror→ earthquake→ signs from heaven, then he would know that the author of Mark had not only omitted several catastrophes, but had also changed their order. The author of Matthew, in his typical fashion, would then have compromised between his two sources, preferring Mark’s shorter list, but adopting Anth.’s sequence.

The question remains why the author of Luke would have wanted to move “earthquake” from its original position. Perhaps it was because he wished to highlight the two natural disasters, earthquake and famine, in Tumultuous Times that he knew had already taken place and that fit into his history of the advance of the Gospel. In the Acts of the Apostles the author of Luke mentions a universal famine that took place during the reign of Claudius (Acts 11:28), and he mentions a “great earthquake” that took place while Paul was imprisoned in Philippi (Acts 16:26). Being conservative with his sources, the author of Luke did not want to change the order of disasters any more than necessary to achieve his purpose. He could have inserted earthquakes after famines, but this would break the natural pairing of famines with pestilence. He could have inserted earthquakes after pestilence, but there were no pestilences he knew of to report in Acts. So he inserted earthquakes ahead of famine even though the famine comes before the earthquake in Acts.

The use of the conjunction τε (te, “and”) is typical of the author of Luke’s writing style,[37] and, therefore, should probably be regarded as Lukan redaction both in L5 and in L9.

Comparison of the Order of Catastrophes

L6 καὶ κατὰ τόπους (Luke 21:11). We suspect that when the author of Luke moved “earthquakes” he also inserted the phrase καὶ κατὰ τόπους (kai kata topous, “and in various places,” “and in place after place”), since the distributive use of κατά is especially characteristic of Lukan composition.[38] The addition of the conjunction καί (kai, “and”) had the function of restricting the prepositional phrase to famines and pestilences. These changes were by no means haphazard. The author of Luke knew of only one, extremely localized, earthquake (Acts 16:26), but he was familiar with a famine that affected the entire Roman world (Acts 11:28). Thus, from his backward-looking historical vantage point the author of Luke slightly revised the wording of Jesus’ prophecy in order to fit the facts as he knew them.

L7 λοιμοὶ (Luke 21:11). Although the text of Codex Vaticanus places pestilence ahead of famine, text critics are nearly unanimous in regarding the inverted order in Vaticanus as secondary. We agree. Not only is the textual evidence against Vaticanus, the order sword→ famine→ pestilence in Jeremiah (which stands behind Tumultuous Times) and the order wars→ famine→ pestilence in Rev. 6 (which bears witness to Tumultuous Times) indicate that famine probably came before pestilence in the original text of Luke.[39] Moreover, we think it was precisely in order to associate earthquake with famine that the author of Luke moved earthquake from its original place in the list (see above, Comment to L5). This purpose would not have been achieved if the author of Luke had placed pestilence ahead of famine.

λιμὸς (GR2). In Hebrew the words for famine (רָעָב), pestilence (דֶּבֶר) and earthquake (רַעַשׁ) almost always occur in the singular form. In Greek the noun φόβητρον (fobētron, “terror”) almost always occurs in the plural.[40] It is likely, therefore, that someone along the line of transmission converted the singulars into plurals. In theory, this could have happened as early as the translation from Hebrew into Greek, but we have reason to suspect that it was the author of Luke who made this conversion. In the vision of the seals in Rev. 6, pestilence (Rev. 6:8) and earthquake (Rev. 6:12) are referred to in the singular, which suggests that even in FR’s version of Tumultuous Times the catastrophes enumerated therein were referred to in the singular. A change from singular to plural would have been a Greek stylistic improvement.

καὶ ἔσται λιμὸς (GR1). The placement of the verb ἔσονται (esontai, “they will be”) in Mark and Matthew in L7 is more Hebraic than Luke’s placement of ἔσονται in L8. Perhaps the Markan-Matthean word order reflects the word order in Anth. The plural form of the verb, however, must be ascribed to the author of Luke’s conversion of the singular nouns to plurals.

וְיִהְיֶה רָעָב (HR). In LXX most instances of λιμός (limos, “hunger,” “famine”) occur as the translation of רָעָב (rā‘āv, “hunger,” “famine”).[41] Likewise, the LXX translators rendered almost every instance of רָעָב as λιμός.[42] The noun רָעָב never occurs in the plural form in the Hebrew Scriptures.[43] Neither does the plural form occur in DSS or the Mishnah.

The author of Luke reports that there was a widespread famine during the reign of Claudius (Acts 11:28). This famine took place in the mid- to late 40s C.E.[44] It directly affected Egypt, Judea and Syria, but its economic impact probably sent ripples throughout the Roman Empire.[45] According to Acts, the church in Antioch sent aid to their brothers and sisters in Judea (Acts 11:29-30). Josephus notes that Queen Helena of Adiabene and her son Izates provided famine relief for the inhabitants of Jerusalem (Ant. 20:51-53). According to rabbinic sources, Helena’s son Monobazus depleted his entire fortune by giving alms in years of drought (t. Peah 4:18). It is not certain whether this report refers to the famine in Judea in the time of Claudius or to a different famine.

Ancient sources mention food shortages in Rome in the years 40-41 C.E.,[46] 51 C.E.,[47] 62 C.E.,[48] 64 C.E.[49] and 68-70 C.E.[50] If so many food crises could happen in Rome, the city to which the empire’s vast resources were funneled, we have to assume that famines and food shortages—ancient sources do not clearly differentiate between the two[51] —must have been fairly common between the time of Jesus’ prophecy and the destruction of the Second Temple.

L8 καὶ λειμοὶ ἔσονται (Luke 21:11). As we noted in the previous Comment, although Codex Vaticanus, which we use as the base text for our reconstruction document, has the order pestilences→ famines, the original text of Luke almost certainly had the order famines→ pestilences.

καὶ θάνατος ἔσται (GR2). Numerous scholars believe the author of Luke added “pestilence” to his source because the Greek words λιμός (limos, “famine”) and λοιμός (loimos, “pestilence”) sound similar and regularly appear as a pair.[52] The pairing of famine and pestilence is not unique to Greek, however.[53] It occurs in Hebrew (רָעָב וְדֶבֶר [rā‘āv vedever, “famine and pestilence”]) and Latin (fames et pestilentia [“famine and pestilence”]) as well.[54] Moreover, Jer. 29:18, which likely informed Jesus’ predictions in Tumultuous Times, contains the series sword→ famine→ pestilence, and the vision in Rev. 6, which may be a non-Lukan witness to FR’s version of Tumultuous Times, has the sequence wars→ famine→ pestilence. Therefore, we think it is unlikely that the author of Luke added “and pestilences” on his own initiative.

It is possible, however, that the author of Luke slightly altered FR’s vocabulary. The word for “pestilence” in Rev. 6:8 is θάνατος (thanatos, “death”). That “pestilence” is the intended meaning in Rev. 6:8 is made nearly certain by the revelator’s statement that the horseman named Thanatos is given authority ἀποκτεῖναι ἐν ῥομφαίᾳ καὶ ἐν λιμῷ καὶ ἐν θανάτῳ καὶ ὑπὸ τῶν θηρίων τῆς γῆς (“to kill with the sword, and with famine, and with pestilence [lit., ‘death’], and by the wild beasts of the earth”). Killing with death makes little sense, but killing with pestilence is perfectly understandable.[55] Indeed, we have in Rev. 6:8 another witness to the sequence sword→ famine→ pestilence. If, as we suppose, the revelator based the vision of the seals on FR’s version of Tumultuous Times, it is impossible to explain why he would have changed λοιμός (“pestilence”) to θάνατος (“death”). On the other hand, supposing the author of Luke read θάνατος in FR, writing λοιμοί (“pestilences”)[56] is a perfectly reasonable stylistic improvement.[57] Thus, it appears FR retained a Hebraism—θάνατος in the sense of “pestilence”—from Anth. which the author of Luke removed.

καὶ θάνατος (GR1). As we noted above in Comment to L7, we think the First Reconstructor moved the verb “it will be” to L8.

וְדֶבֶר (HR). The LXX translators consistently rendered דֶּבֶר (dever, “pestilence”) as θάνατος (“death”).[58] The sequence דֶּבֶר→רָעָב→חֶרֶב (sword→ famine→ pestilence), so common in Jeremiah, assures us that דֶּבֶר is the right choice for HR.

In the years between Jesus’ prophecy and the destruction of the Temple pestilence is known to have broken out in Italy (Tacitus, Ann. 16:13; Suetonius, Nero 39:1).[59] Philostratus reports that Apollonius of Tayana predicted an outbreak of pestilence in Ephesus (Vita Apollonii 4:4; 8:7 §10). This pestilence may have occurred in the 40s C.E.

L9 καὶ φόβητρον (GR2). As we noted above in Comment to L7, we believe the author of Luke was responsible for converting singular nouns in FR’s version of Tumultuous Times into plurals. With respect to the noun φόβητρον (fobētron, “terror”), he would have had every incentive for doing so, since φόβητρον almost always occurs in the plural.[40] The sole instance of φόβητρον in LXX (Isa. 19:17) is an exception.

Probably the author of Luke was also responsible for dropping the conjunction καί (kai, “and”) at the beginning of L9 in order to write τε (te, “both”) at the end, for, as we noted above, in Comment to L5, the use of the conjunction τε was typical of the author of Luke’s personal writing style. By writing τε (te kai, “both”) in L9 the author of Luke coupled “terrors” (L9) with the “signs” (L10), with the result that both the “terrors” and the “signs” were now understood to come from heaven.

וּפַחַד (HR). The noun φόβητρον (fobētron, “terror”) occurs only once in LXX, where it serves as the equivalent of חָגָּא (ḥāgā’, “terror”; Isa. 19:17). Since חָגָּא fell into disuse in Mishnaic Hebrew, we do not consider it to be a viable option for HR. Delitzsch rendered φόβητρα (fobētra, “terrors”) in Luke 21:11 as מוֹרָאִים (mōrā’im, “terrors”), probably on the basis of Deut. 4:34, the only time מוֹרָא (mōrā’, “fear,” “terror”) occurs in the plural. Lindsey suggested reconstructing φόβητρα as נוֹרָאוֹת (nōrā’ōt, “awe-inspiring deeds”).[60] Other options for reconstructing φόβητρον include אֵימָה (’ēmāh, “fear”), חֲרָדָה (ḥarādāh, “fear,” “trembling”) and יִרְאָה (yir’āh, “fear”). We have preferred פַּחַד (paḥad, “fear,” “terror”) because of its generally negative connotation.

Above in Comment to L5 we suggested that “terror” and “earthquake” in Tumultuous Times represent two interpretations of זועה in the written text of Jer. 29:18. In Biblical Hebrew זְוָעָה (zevā‘āh) meant “terror,” but in Mishnaic Hebrew זְוָעָה meant “earthquake.” In order to represent these two distinct meanings, a midrashist might choose two completely distinct and unambiguous terms: for example, פַּחַד to represent the interpretation of זועה in the sense of “terror,” and רַעַשׁ to represent the interpretation of זועה in the sense of “earthquake.”

An analogous example of this midrashic technique is found in the Rule of the Community discovered at Qumran, where we find an attempt to interpret the difficult word מְאֹדֶךָ (me’odechā, “your very [?]”) in the command to love God with all one’s heart and soul and whatever מְאֹדֶךָ might mean (Deut. 6:5).[61] The LXX translators interpreted מְאֹדֶךָ as τῆς δυνάμεώς σου (tēs dūnameōs sou, “your power,” “your strength”). In rabbinic literature we find that the sages interpreted מְאֹדֶךָ as meaning “your wealth” or “your property” (cf., e.g., Sifre Deut. §32 [ed. Finkelstein, 55]). Both of these interpretations of מְאֹדֶךָ, plus an additional one, appear to be combined in the Rule of the Community:

וכול הנדבים לאמתו יביאו כול דעתם וכוחם והונם ביחד אל

And all the volunteers to his truth must bring all their knowledge and all their strength and all their property into the community of God. (1QS I, 11-12)

According to this text, loving God with all one’s מְאֹד entails putting all one’s resources (mental, physical and fiscal) at the disposal of the sect. Note that although דַּעַת (da‘at, “knowledge”), כֹּחַ (koaḥ, “strength”) and הוֹן (hōn, “property,” “wealth”) appear to be interpretations of מְאֹד, the word מְאֹד does not appear in this passage from the Rule of the Community. In the same way, although we believe “terror” and “earthquake” represent two interpretations of זועה in the written text of Jer. 29:18, the noun זְוָעָה does not occur in our Hebrew reconstruction of Tumultuous Times.

L10 καὶ σεισμὸς μέγας (GR2). Since Rev. 6:12, which may be dependent upon FR’s version of Tumultuous Times, describes a σεισμὸς μέγας (seismos megas, “big earthquake”), it is likely that the adjective “big” modified “earthquake” in FR, just as “big” modifies “earthquakes” in Luke 21:11 (L5). When the author of Luke told the story of Paul’s imprisonment in Philippi, he described the earthquake as “big,” even though the earthquake appears not to have affected any place but Paul’s prison. There is no indication in Acts 16 that the jailor’s house nearby was damaged, and since the city magistrates in Philippi were able to carry on with their usual business the following morning, the “big” earthquake could not have done much damage elsewhere in the city. Perhaps the author of Luke described this inconsequential tremor in Philippi as a “big earthquake” because he wished to show that Jesus’ predictions in Tumultuous Times had begun to take place.

καὶ σεισμὸς (GR1). Although we believe “earthquake” was modified by the adjective “big” in FR, we do not think “earthquake” was modified by an adjective in Anth. None of the other terrestrial calamities listed in Tumultuous Times take an adjective, and no adjectives appear in Jer. 29:18, from which the list of calamities is derived. Perhaps the First Reconstructor added the adjective “big” to “earthquake” in imitation of the “big signs” from heaven mentioned in L13.

וְרַעַשׁ (HR). In LXX almost every instance of σεισμός (seismos, “earthquake”) occurs as the translation of רַעַשׁ (ra‘ash, “earthquake”).[62] Likewise, the LXX translators rendered most instances of רַעַשׁ as σεισμός.[63] Although זְוָעָה (zevā‘āh; almost always occurring in the plural) came to mean “earthquake” in Mishnaic Hebrew, it did not totally displace רַעַשׁ, which continued to be used. As we discussed above in Comment to L9, we think “terror” and “earthquake” in Tumultuous Times is based on a double interpretation of זועה in the written text of Jer. 29:18. Precisely because the meaning of זועה is ambiguous in Jer. 29:18, it is likely that the double interpretation of this term would have used two unambiguous terms meaning “terror” and “earthquake.” We therefore regard רַעַשׁ as preferable for HR.

There is ample evidence from ancient sources to demonstrate that earthquakes were regarded as omens of catastrophe and portents of destruction. This is clearly stated by Pliny the elder:

Nor yet is the disaster a simple one, nor does the danger consist only in the earthquake itself, but equally or more in the fact that it is a portent; the city of Rome was never shaken without this being a premonition of something about to happen. (Nat. 2:86 §200; Loeb)[64]

Similarly, in his account of the war in Jerusalem, Josephus described how the city was struck by a powerful storm and an earthquake. He interpreted the meaning of these natural phenomena in the following manner:

Such a convulsion of the very fabric of the universe clearly foretokened destruction for mankind, and the conjecture was natural that these were portents of no trifling calamity. (J.W. 4:287; Loeb)[65]

In rabbinic literature, too, we find the view that earthquakes are indicative of coming political and social upheavals:

אמר רבי שמואל אין רעש אלא הפסק מלכות

Rabbi Shmuel said, “There is no earthquake except [as a sign of] the end of a kingdom.” (y. Ber. 9:2 [64a])

Numerous earthquakes occurred in the years between Jesus’ prophecy and the destruction of the Temple, as the following table shows.

Earthquakes between Jesus’ Prophecy and the Destruction of the Temple

| Date | Location | Source |

| 26-36 C.E. | Ein Gedi (Judea) | Geological Survey[66] |

| 37 C.E. | Capri (Italy)[67] | Suetonius, Tib. 74:2[68] |

| 37 C.E. | Antioch (Syria)[69] | John Malalas, Chronographia 10:18-19 §243-244[70] |

| 41-54 C.E. (42-43 or 46-47 C.E.?) | Ephesus, Smyrna (Asia Minor)[71] | John Malalas, Chronographia 10:23 §246[72] |

| 41-54 C.E. (42-43 or 46-47 C.E.?) | Smyrna, Miletus, Chios and Samos (Asia Minor)[73] | Philostratus, Vit. Apoll. 4:6[74] |

| 41-54 C.E. (46-47 C.E.?) | Antioch (Syria)[75] | Philostratus, Vit. Apoll. 6:38; John Malalas, Chronographia 10:23 §246[76] |

| mid-1st cent. C.E. | Hellespont (European-Asia Minor border)[77] | Philostratus, Vit. Apoll. 6:41[78] |

| ca. 51 C.E. | Philippi (Greece)[79] | Acts 16:26[80] |

| 51 C.E. | Rome (Italy)[81] | Tacitus, Ann. 12:43[82] |

| 53-54 C.E. | Apamea in Phrygia (Asia Minor)[83] | Tacitus, Ann. 12:58[84] |

| 53-54 C.E. | Crete, Rhodes[85] | Pliny, Nat. 7:16 §73;[86] John Malalas, Chronographia 10:28 §250[87] |

| 60 C.E. | Laodicea, Hierapolis, Colossae (Asia Minor)[88] |

Tacitus, Ann. 14:27;[89] Sibylline Oracles 4:107-108; 5:290-291; 12:279-281[90] |

| 61 or 62 C.E. | Achaia (Greece)[91] |

Seneca, Nat. 6:1 §13; 6:25 §3-4[92] |

| 61 or 62 C.E. | Macedonia (Greece)[91] | Seneca, Nat. 6:1 §13[93] |

| 62 or 63 C.E. | Pompeii, Herculaneum, Nuceria, Naples (Italy)[94] | Seneca, Nat. 6:1 §1-3;[95] Tacitus, Ann. 15:22[96] |

| 64 C.E. | Naples (Italy)[97] | Suetonius, Nero 20:2[98] |

| 62-66 C.E. | Crete[99] | Philostratus, Vit. Apoll. 4:34[100] |

| 65-72 C.E. | Delos[101] | Pliny, Nat. 4:12 §66[102] |

| 67 C.E. | Jerusalem (Judea)[103] | Josephus, J.W. 4:286-287[104] |

| 68 C.E. | Lycia (Asia Minor)[105] | Sibylline Oracles 4:109-113;[106] Dio Cassius, Roman History 63:26 §5[107] |

| 68 C.E. | Rome (Italy)[108] | Suetonius, Nero 48:2;[109] Dio Cassius, Roman History 63:27 §1[110] |

| 68-69 C.E. | Nicomedia, Bithynia (Asia Minor)[111] | John Malalas, Chronographia 10:43 §259[112] |

L11 κατὰ τόπους (Matt. 24:7). The author of Matthew picked up the phrase κατὰ τόπους (kata topous, “in places”) from Mark in L6.

L12 וּמִן הַשָּׁמַיִם (HR). On reconstructing οὐρανός (ouranos, “sky,” “heaven”) with שָׁמַיִם (shāmayim, “sky,” “heaven”), see Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, Comment to L39.

The phrase ἀπ᾿ οὐρανοῦ (ap ouranou, “from heaven”) also occurs in Days of the Son of Man (L30), where we reconstructed it as מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם.

For examples of the phrase מִן הַשָּׁמַיִם in rabbinic sources, see Return of the Twelve, Comment to L17.

L13 σημεῖα μεγάλα (GR2). It is likely that the author of Luke added the verb ἔσται (estai, “it will be”) in L13. The additional verb would have helped him to balance his reorganized lists of terrestrial and astronomical phenomena, which he crafted into two separate sentences. We have accordingly omitted ἔσται from our reconstructions of FR (GR2) and Anth. (GR1).

Note the placement of the adjective (μεγάλα) after the noun (σημεῖα), which agrees with Hebrew syntax.

סִימָנִים גְּדוֹלִים (HR). On reconstructing σημεῖον (sēmeion, “sign”) with סִימָן (simān, “sign”), see Sign-Seeking Generation, Comment to L29.

On reconstructing μέγας (megas, “big”) with גָּדוֹל (gādōl, “big”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L22.

Examples of סִימָן גָּדוֹל (simān gādōl, “big sign”) occur in rabbinic sources, for instance:

אמ′ ר′ יְהוּדָה וַהֲלֹא סִימָן גָּדוֹל הָיָה לָהֶם שְׁלוֹשֶׁת מִילִים מִירוּשָׁלַםִ וְעַד בֵּית חֲרוֹרוֹ הוֹלְכִים מִיל וְחוֹזְרִים מִיל וְשׁוֹהִים כְּדֵי מִיל וְיוֹדְעִים שֶׁהִיגִּיַע שָׂעִיר לַמִּדְבָּר

Rabbi Yehudah said, “And did they not have a big sign [סִימָן גָּדוֹל]? It is three miles from Jerusalem to Bet Haroro. They would walk a mile, and return a mile, and wait long enough to go another mile, and they would know that the scapegoat had reached the desert.” (m. Yom. 6:8)

רבן שמעון בן גמליאל או’ פרוסות סימן גדול לאורחין כל זמן שאורחין רואין את הפרוסות יודעין שדבר אחר בא

Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel said, “Pieces of bread are a big sign [סִימָן גָּדוֹל] to guests. As long as the guests see the pieces of bread they know that something else [i.e., another dish—DNB and JNT] is coming.” (t. Ber. 4:14; Vienna MS)

In these examples the connotation of “big sign” is something like “clear indication.” Ancient people did not always make the same distinction between the mundane and the supernatural that we do today, so it is possible that Jesus had in mind natural phenomena such as comets or eclipses of the sun and moon when he referred to signs from heaven.

In rabbinic literature we find that certain astronomical phenomena were regarded as signs of coming punishment:

היה ר′ מאיר או′ בזמן שהמאורות לוקין סימן רע לשונאיהן של ישראל מפני שהן למודי מכות משל לסופר שנכנס לבית הספר ואמ′ הביאו לי רצועה מי הוא דואג מי שלמוד להיות לוקה

Rabbi Meir used to say, “In a time when the heavenly lights are eclipsed, it is a bad sign for the haters of Israel [a euphemism for Israel itself—DNB and JNT], for they are accustomed to injuries. A parable: [It may be compared] to a scribe who entered a schoolhouse and said, ‘Bring me a strap.’ Who is afraid? The one who is accustomed to being strapped.” (t. Suk. 2:6; Vienna MS)

According to NASA’s “World Atlas of Solar Eclipse Paths,” solar eclipses visible in the Mediterranean region occurred on 20 May 49 C.E., 30 April 59 C.E. and 31 May 67 C.E. NASA’s “Five Millennium Catalog of Lunar Eclipses” lists around 95 lunar eclipses that took place in the years between Jesus’ prophecy and the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E. Of these, 19 were total eclipses of the moon. Probably not all of these were visible to the inhabitants of the Roman world, either because of cloud cover or because that part of the earth was turned away from the moon at the time of the eclipse, but many of the eclipses would have been observed. Josephus mentions the appearance of a star over Jerusalem that resembled a sword and a comet that remained visible for a year at some point prior to the Temple’s destruction (J.W. 6:289).[113] Josephus interpreted both astronomical phenomena as portents that the Temple’s destruction was at hand.

That Jesus expected the portents of the Temple’s destruction would be manifested in heaven and on earth is characteristic of the cosmic significance first-century Jews ascribed to the Temple. Josephus described the universal significance of the Temple in this way:

εἷς ναὸς ἑνὸς θεοῦ…κοινὸς ἁπάντων κοινοῦ θεοῦ ἁπάντων

One Temple of the one God…shared by everyone as God is everyone’s. (Ag. Ap. 2:193; Loeb)[114]

Similarly, in a speech Josephus attributed to the high priest Jesus of Gamla we read:

…[this] spot [i.e., the site of the Temple—DNB and JNT]…is revered by the world and honoured by aliens from the ends of the earth who have heard of its fame…. (J.W. 4:262; Loeb)

Many first-century Jews believed the Temple’s architecture and furniture were models of the cosmos. Philo described it in the following manner:

The ark…is the coffer of the laws, for in it are deposited the oracles which have been delivered. But the cover, which is called the mercy-seat, serves to support the two winged creatures which in the Hebrew are called cherubim…. Some hold that, since they are facing each other, they are symbols of the two hemispheres, one above the earth and one under it, for the whole heaven has wings…. The altar of incense he set in the middle [of the sanctuary—DNB and JNT], a symbol of the thankfulness for earth and water…, since the middle position in the universe has been assigned to them. The candlestick is placed at the south, figuring thereby the movements of the luminaries above; for the sun and the moon and the others run their courses in the south far away from the north. And therefore six branches, three on each side, issue from the central candlestick, bringing up the number to seven, and on all these are set seven lamps and candlebearers, symbols of what the men of science call planets. For the sun, like the candlestick, has the fourth place in the middle of the six and gives light to the three above and three below it…. The table is set at the north and has bread and salt on it, as the north winds are those which most provide us with food, and food comes from heaven and earth, the one sending rain, the other bringing their seeds to their fullness when watered by the showers. In line with the table are set the symbols of heaven and earth, as our account has shewn, heaven being signified by the candlestick, earth and its parts…by the altar of incense. (Moses 2:97-98, 101-105; Loeb)

Like Philo, Josephus also believed that the Temple was a microcosm of creation:

For if one reflects on the construction of the tabernacle…and the vessels which we use for the sacred ministry, he will discover that…every one of these objects is intended to recall and represent the universe…. Thus, to take the tabernacle, …by dividing this into three parts and giving up two of them to the priests, as a place approachable and open to all, Moses signifies the earth and the sea, since these too are accessible to all; but the third portion he reserved for God alone, because heaven also is inaccessible to men. Again, by placing upon the table the twelve loaves, he signifies that the year is divided into as many months. By making the candelabrum to consist of seventy portions, he hinted at the ten degree provinces of the planets, and by the seven lamps thereon the course of the planets themselves, for such is their number. The tapestries woven of four materials denote the natural elements: thus the fine linen appears to typify the earth, because from it springs up the flax, and the purple the sea, since it is incarnadined with the blood of fish; the air must be indicated by the blue, and the crimson will be the symbol of fire. (Ant. 3:180-183; Loeb)

The Temple not only modeled the universe, it was a source of universal blessing. According to the high priest Shimon haTzadik, the Temple helped to hold the cosmos together:

עַל שְׁלֹשָׁה דְבָרִים הָעוֹלָם עוֹמֵד עַל הַתּוֹרָה וְעַל הָעֲבֹדָה וְעַל גְּמִילוּת חֲסָדִים

The world stands on three things: on the Torah, on the divine service [in the Temple—DNB and JNT], and on acts of benevolence. (m. Avot 1:2)

Mourning its loss, Rabbi Yohanan said:

אוי להם <לעובדי כוכבים> {לאומות העולם} שאבדו ואין יודעין מה שאבדו בזמן שבהמ″ק קיים מזבח מכפר עליהן ועכשיו מי מכפר עליהן

Woe to them (to the idolators) [to the peoples of the world]! For they have lost and know not what they have lost. When the Temple existed the altar atoned for them. But now, who will atone for them? (b. Suk. 55b)

In view of the cosmic significance of the Temple, it is only natural that both heaven and earth would shudder with premonitions of the Temple’s demise.

L14-15 The description of the calamities mentioned in Tumultuous Times as “the beginning of labor pains” is found in Matthew and Mark, but not in Luke. The First Reconstructor could have omitted “these are the beginning of birthing pains,” a forward-looking phrase, because in his very next sentence he was about to write “but before all this” (Luke 21:12), a backward-looking phrase.[115] In that case, FR’s omission of “these are beginning of birthing pains” would account for the absence of these words in Luke.

On the other hand, the author of Mark could have added the reference to birthing pains on his own.[116] But since applying the image of labor pains to times of intense social and political distress, including foreign invasions and siege, is not alien to Jewish thought (cf. Isa. 37:3; Jer. 6:24; 13:21), it is by no means impossible that Jesus could have compared the portents of coming destruction to the onset of labor pains. Moreover, Mark’s wording is not un-Hebraic, even if we have not succeeded in finding an exact parallel to “beginning of birthing pains” in ancient Hebrew sources.[117] So it is possible that the author of Mark picked up “these are the beginning of labor pains” from Anth.

In view of these considerations, we have tentatively accepted Mark’s wording in L15 for GR, but we have indicated our uncertainty by placing it in brackets. HR is bracketed too.

L14 πάντα δὲ (Matt. 24:8). Just as we concluded that the author of Matthew inserted the word πάντα (panta, “all”) in L14 of Temple’s Destruction Foretold in order to create the phrase ταῦτα πάντα (tavta panta, “all these things”), so we suspect that the author of Matthew inserted πάντα in L14 of Tumultuous Times in order to create the phrase πάντα δὲ ταῦτα (panta de tavta, “but all these things”). We have accordingly omitted Matthew’s πάντα δέ from GR1.

L15 [תְּחִילַּת חֲבָלִים אֵלּוּ] (HR). In LXX when the noun ἀρχή (archē) occurs in the sense of “beginning,” it usually does so as the translation of רֹאשׁ (ro’sh, “head,” “beginning”) or רֵאשִׁית (rē’shit, “beginning”).[118] Therefore, it is not surprising that Delitzsch and Lindsey[119] rendered ἀρχή as רֵאשִׁית in their respective Hebrew translations of Mark 13:8.[120] Although רֵאשִׁית persisted in Mishnaic Hebrew, it began to be supplanted by תְּחִילָּה (teḥilāh, “first,” “beginning”), and since we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in Mishnaic-style Hebrew, we have preferred תְּחִילָּה for HR.

Examples of תְּחִילָּה in the construct state meaning “beginning of” include:

מְנַיִין הוּא מַתְחִיל מִתְּחִילַּת הַבְּרָכָה שֶׁטַעָה זֶה

Where does he [i.e., the person who made a mistake—DNB and JNT] begin? From the beginning of the blessing in which he made a mistake. (m. Ber. 5:3)

נוֹתְנִין פֵּיאָה מִתְּחִילַּת הַשָּׂדֶה [וּ]מֵאֶמְצָעָהּ

They give peah from the beginning of the field and from its middle. (m. Peah 1:3)

וְאִם עֲשָׂאָהּ לְשֵׁם הֶחָג אֲפִילּוּ מִתְּחִילַּת הַשָּׁנָה כְּשֵׁירָה

…but if he made it [i.e., a sukkah—DNB and JNT] for the sake of the feast, then even [if he made it] from the beginning of the year it is valid. (m. Suk. 1:1)

In LXX ὠδίν (ōdin, “pain,” “labor pain”) occurs more often as the translation of חֵבֶל (ḥēvel, “pain,” “labor pain”) than of any other alternative.[121] Likewise, the LXX translators rendered most instances of חֵבֶל as ὠδίν.[122]

Neither the phrase רֵאשִׁית (הַ)חֲבָלִים (rē’shit [ha]ḥavālim, “[the] beginning of [the] birthing pains”) nor תְּחִילַּת (הַ)חֲבָלִים (teḥilat [ha]ḥavālim, “[the] beginning of [the] birthing pains”) occurs in MT, DSS or rabbinic sources.

We prefer to use the Mishnaic demonstrative pronoun אֵלּוּ (’ēlū, “these”), which replaced Biblical אֵלֶּה (’ēleh, “these”), since in L15 we are reconstructing direct speech.

Scholars have long connected the reference to the “beginning of birthing pains” in Tumultuous Times to the rabbinic concept of חֶבְלוֹ שֶׁלְּמָשִׁיחַ (ḥevlō shelmāshiaḥ, “the Messiah’s birthing pain”).[123] However, as other scholars have noted, there is an important difference between the birthing pains spoken of in Tumultuous Times and the birthing pain of the Messiah. The birthing pain of the Messiah refers to acute distress that will come prior to the final redemption, whereas Tumultuous Times refers to human catastrophes and natural disasters that signal the beginning of the outpouring of divine wrath.[124] Therefore, if Jesus did refer to birthing pains in Tumultuous Times, it is preferable to regard this in light of the scriptural imagery of judgment rather than as an allusion to the Jewish expectation of acute sufferings as a prelude to redemption.[125]

Redaction Analysis

Considerable redaction of Tumultuous Times took place in the course of its transmission. Nevertheless, the main features of this important pericope in Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption have been preserved.

First Reconstruction’s Version[126]

| Tumultuous Times | |||

| First Reconstruction | Anthology | ||

| Total Words: |

25 | Total Words: |

25 [28] |

| Total Words Identical to Anth.: |

22 | Total Words Taken Over in FR: |

22 |

| % Identical to Anth.: |

88.00 | % of Anth. in FR: |

88.00 [78.57] |

| Click here for details. | |||

Because the vision of the seals in Rev. 6 likely bears witness to FR’s version of Tumultuous Times, we have in this pericope a rare opportunity to distinguish between FR’s redactional activity and Lukan redaction. It appears that the First Reconstructor was responsible for paraphrasing Anth.’s wording in L1, improving Anth.’s Greek in L3 (ἐπί→ἐπ᾿), moving the verb from L7 to L8, adding μέγας (megas, “big”) in L10, and possibly dropping the concluding statement “these are the beginning of birthing pains” in L15. These changes to Anth.’s wording are relatively minor and do not affect the overall sense of the pericope.

Luke’s Version[127]

| Tumultuous Times | |||

| Luke | Anthology | ||

| Total Words: |

29 | Total Words: |

25 [28] |

| Total Words Identical to Anth.: |

17 | Total Words Taken Over in Luke: |

17 |

| % Identical to Anth.: |

58.62 | % of Anth. in Luke: |

68.00 [60.71] |

| Click here for details. | |||

The author of Luke’s redactional activity in Tumultuous Times was far more extensive than the First Reconstructor’s. The author of Luke rearranged the order of the items in the list of terrestrial catastrophes and converted the singular nouns to plurals. The author of Luke probably moved “earthquakes” to the head of the list of natural catastrophes (L5) because he wished to highlight the two natural disasters (earthquake and famine) that were to play a role in the later history of the church as recorded in Acts. By adding the phrase κατὰ τόπους to L6, he was able to restrict its reference to famines and pestilences. This served his purpose because famine was the only widespread natural catastrophe of which he was aware. In L8 the author of Luke changed θάνατος (thanatos, “death”), used in FR in the sense of “pestilence,” to λοιμοί (loimoi, “pestilences”) because in Greek sources λιμός (“famine”) and λοιμός (“pestilence”) are a stereotypical pair. The author of Luke’s rearrangement of the items also included the association of “terrors” with “big signs,” with the result that both items were understood to come “from heaven.” Some of the author of Luke’s changes were stylistic improvements (converting singular nouns to plurals), but most of his changes appear to have been motivated by his desire to demonstrate that Jesus’ prophecy had been fulfilled in the events recorded in Acts.

Mark’s Version[128]

| Tumultuous Times | |||

| Mark | Anthology | ||

| Total Words: |

18 | Total Words: |

25 [28] |

| Total Words Identical to Anth.: |

8 [11] | Total Words Taken Over in Mark: |

8 [11] |

| % Identical to Anth.: |

44.44 [61.11] | % of Anth. in Mark: |

32.00 [39.29] |

| Click here for details. | |||

One of the author of Mark’s most significant changes to Tumultuous Times was to omit in L1 an introductory phrase in indirect speech. By adding γάρ (gar, “for”) in L2, the author of Mark succeeded in merging Tumultuous Times with the preceding pericope (Like Lightning) with the result that Tumultuous Times became the grounds for the exhortation given in Like Lightning. The other major change made by the author of Mark was also one of omission. He greatly reduced the number of signs listed in Tumultuous Times, omitting pestilences, terrors and big signs from heaven (L8-13). On the other hand, from his knowledge of Anth. the author of Mark may have restored the comparison of the signs mentioned in Tumultuous Times to the beginning of birthing pains (L15).

Matthew’s Version[129]

| Tumultuous Times | |||

| Matthew | Anthology | ||

| Total Words: |

21 | Total Words: |

25 [28] |

| Total Words Identical to Anth.: |

10 [13] | Total Words Taken Over in Matt.: |

10 [13] |

| % Identical to Anth.: |

47.62 [61.90] | % of Anth. in Matt.: |

40.00 [46.43] |

| Click here for details. | |||

Matthew’s version of Tumultuous Times is heavily influenced by Mark’s. The author of Matthew’s change of ἐπ᾿ ἔθνος to ἐπὶ ἔθνος in L3 may be a reflection of Anth.’s wording. In L14-15 the author of Matthew was probably responsible for changes of word order and the addition of πάντα δέ.

Results of This Research

1. Do the events described in Tumultuous Times depict premonitions of the Temple’s destruction, or are they “the birthing pain of the Messiah” leading up to redemption? Some scholars have assumed that the calamities and disasters mentioned in Tumultuous Times are of an exclusively eschatological character and therefore conclude that Tumultuous Times must be out of its proper sequence in Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption. These scholars prefer to view the portents described in Tumultuous Times as heralding the Son of Man’s coming. We dispute the assumption that the portents mentioned in Tumultuous Times are necessarily eschatological. Ancient Jewish, Greek and Roman authors mention earthquakes and astronomical phenomena as harbingers of greater calamities to come without connecting those greater calamities to the end of history. The scriptural prophets, especially Jeremiah, predicted that war, famine and plague would come upon Israel as punishment for disobeying the covenant, but he did not entertain the notion that these punishments would mark the end of time. Given the cosmic significance first-century Jews attributed to the Temple, it is hardly surprising that Jesus expected that the Temple’s destruction would be foreshadowed by disturbances throughout the cosmos. Therefore, we see no justification for relating the portents described in Tumultuous Times to the Son of Man’s coming or to the concept of “the birthing pain of the Messiah,” which was a prelude to redemption rather than a premonition of divine judgment.

2. Did the events Jesus predicted take place? Or was he wrong? Or are they yet to happen? Human calamities (warfare between peoples and empires), natural disasters (famine, pestilence, earthquake) and astronomical phenomena (eclipses, comets) of the kind Jesus described in Tumultuous Times are documented in the years between Jesus’ prophecy and the destruction of the Temple. Of course, these phenomena are typical of every era of human history, so the fulfillment of Jesus’ prophecy is perhaps not so remarkable. Still, interpreting political events as the unfolding of a divine plan and ascribing religious significance to natural phenomena is what all prophets do. True prophets give the “right” interpretation to these events, while false prophets interpret such happenings in a manner that only increases calamity. Whereas many of Jesus’ contemporaries were convinced that the signs all pointed to the success of a militant Jewish uprising against the Roman Empire, Jesus interpreted the social and political upheavals of his time and the groanings of nature as evidence that Israel was headed for destruction. Jesus’ prophetic insight was borne out by the tragic events of 70 C.E., while the charlatans who stoked militant nationalist sentiments were proved false.

Conclusion

In Tumultuous Times Jesus foretold various signs that would indicate that the destruction of the Temple was approaching.

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Notes

- For abbreviations and bibliographical references, see “Introduction to ‘The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction.’” ↩

- This translation is a dynamic rendition of our reconstruction of the conjectured Hebrew source that stands behind the Greek of the Synoptic Gospels. It is not a translation of the Greek text of a canonical source. ↩

- On the Anth. block of Son of Man material in Luke 17, see Days of the Son of Man, under the subheading “Story Placement.” ↩

- Cf. Bundy, 460 §362. ↩

- Cf. Rev. 6:8, which mentions sword, famine, death (= pestilence) and wild beasts. ↩

- According to Josephus, omens of the Temple’s destruction included the opening of the locked gates of the Temple of their own accord, the voices of invisible speakers in the Temple, the manifestation of apparitions in the sky above the Temple, and the birth of deformed animals on the Temple Mount (J.W. 6:289-300). Rabbinic sources, too, mention the gates of the Temple opening of their own accord, as well as other inauspicious signs (y. Yom. 6:3 [33b]). ↩

- Pace Manson, Sayings, 325; David Flusser, “Jerusalem in Second Temple Literature” (Flusser, JSTP2, 44-75, esp. 71-72); idem, Jesus, 238 n. 5; R. Steven Notley, “Learn the Lesson of the Fig Tree” (JS1, 105-120, esp. 111). ↩

- Scholars who sought to join Luke 21:10-11 to Luke 21:25ff. typically believed that in addition to Mark 13 the author of Luke used a non-Markan source as the basis for the discourse in Luke 21. Such scholars include Manson (Sayings, 325) and Gaston (356-357). See Lloyd Gaston, No Stone On Another: Studies in the Significance of the Fall of Jerusalem in the Synoptic Gospels (Leiden: Brill, 1970), 357, where he admits that the fusing of Luke 21:10-11 to Luke 21:25 is the weakest part of his reconstruction.

Lindsey, who believed that the Gospel of Luke was written prior to (and thus independently of) Mark’s, believed that Luke 21:10-11 originally belonged to a prophecy on the eschatological coming of the Son of Man that was unconnected to Jesus’ prophecy of destruction and redemption until the First Reconstructor wove these two prophecies together. Flusser (“Jerusalem in Second Temple Literature,” 71-72) adopted Lindsey’s opinion. ↩ - Lindsey treated Luke 21:8-11 (Like Lightning and Tumultuous Times) as a single pericope (evidently he did not notice that the phrase τότε ἔλεγεν αὐτοῖς in Luke 21:10 breaks these verses into two pericopae) and assigned all these verses to a prophecy concerning the eschatological coming of the Son of Man. See Lindsey, JRL, 168; idem, TJS, 73; idem, “From Luke to Mark to Matthew: A Discussion of the Sources of Markan “Pick-ups” and the Use of a Basic Non-canonical Source by All the Synoptists,” under the subheading “An Examination of the Editorial Activity of the First Reconstructor.” ↩

- Some scholars have supposed that for Tumultuous Times the author of Luke relied (at least partially) on a non-Markan source in addition to Mark 13:8. See Knox, 1:105; Gaston, No Stone on Another, 16; Bovon, 3:111. See also Paul Winter, “The Treatment of his Sources by the Third Evangelist in Luke XXI‐XXIV,” Studia Theologica 8.1 (1954): 138-172, esp. 148-149. Taylor, on the other hand, despite believing that in Luke 21 the author of Luke frequently had recourse to a non-Markan source, did not believe the author of Luke made use of a non-Markan source for Tumultuous Times. See Vincent Taylor, “A Cry from the Siege: A Suggestion Regarding A Non-Marcan Oracle Embedded in Lk. xxi 20-36,” Journal of Theological Studies 26.102 (1925): 136-144, esp. 136. ↩

- See R. H. Charles, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Revelation of St. John (2 vols.; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1920), 1:158-160; Craig R. Koester, Revelation: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (AB 38a; New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2014), 357-358. ↩

- On the four horsemen in Rev. 6, see Jack Poirier’s JP article, “The Interpretive Key to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.” ↩

- Charles, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Revelation of St. John, 1:158-160. ↩

- For a detailed discussion, see Son of Man’s Coming, under the subheading “Conjectured Stages of Transmission.” ↩

- See Charles, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Revelation of St. John, 1:158-160. ↩

- Luke’s reference to “terrors” parallel to Revelation’s reference to persecution is one case in which we think that Luke preserves the more primitive version. The revelator may have interpreted “terrors” as persecutions because, following Tumultuous Times, FR’s version of Jesus’ prophecy went on to describe coming persecutions (cf. Matt. 24:9-14; Mark 13:9-13; Luke 21:12-19). ↩

- See Temple’s Destruction Foretold, Comment to L40. ↩

- See the introduction to the “Destruction and Redemption” complex. ↩

- Cf. Manson, Sayings, 326. ↩

- See Knox, 1:105. ↩

- See Bundy, 460-461 §362; Bovon, 3:111. For a different view, see Fitzmyer, 2:1137. ↩

- See Introduction to “The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction,” under the subheading “Arrangement of the Reconstruction.” ↩

- Buth noted that there are only two instances of narrative τότε in the narrative framework of Luke’s Gospel (Luke 21:10; 24:45). See Randall Buth, “Distinguishing Hebrew from Aramaic in Semitized Greek Texts, with an Application for the Gospels and Pseudepigrapha” (JS2, 247-319, esp. 310). ↩

- Lindsey regarded the third-person singular and plural imperfect forms ἔλεγεν (elegen, “he was saying”) and ἔλεγον (elegon, “they were saying”) in Luke as redactional. See Robert L. Lindsey, “A New Two-source Solution to the Synoptic Problem,” thesis 7. ↩

- Plummer (Luke, 478) noted that Tumultuous Times contains the only NT instance of ἐγείρειν + ἐπί in the sense of “rise up against” someone. ↩

- See David Flusser, “The Hubris of the Antichrist in a Fragment from Qumran” (Flusser, JOC, 207-213, esp. 208). ↩

- See the entry for βασιλεία in LOY Excursus: Greek-Hebrew Equivalents in the LOY Reconstructions. For our justification, see Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, Comment to L39. ↩

- See Gundry, Use, 46-47; Gaston, No Stone On Another, 14; Marshall, 765; Nolland, Matt., 963. ↩

- Isaiah 19:2 belongs to an oracle uttered against Egypt. Therefore, the usefulness of an allusion to this verse in the context of a prophecy of the destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple is dubious. ↩

- This is the approach taken by Bo Reicke, “Synoptic Prophecies on the Destruction of Jerusalem,” in Studies in the New Testament and Early Christian Literature: Essays in Honor of Allen P. Wikgren (ed. David Edward Aune; Leiden: Brill, 1972), 121-134. ↩

- Cf. Nolland, Matt., 963. ↩

- Cf. Herbert W. Basser, The Gospel of Matthew and Judaic Traditions: A Relevance-based Commentary (Leiden: Brill, 2015), 626. ↩

- In both verses there is a discrepancy between the written (ketiv) and vocalized (qere) readings of the text. ↩

- See Jastrow, 389. ↩

- Opposite לזועה in Jer. 29:18 the Jeremiah Targum reads לְזִיעַ. The Aramaic noun זִיעַ (zia‘) can mean either “earthquake” or “trembling.” See Jastrow, 395. In his English translation of the Jeremiah Targum, Hayward rendered Jer. 29:18 as “And I will pursue them with the sword, with the famine, and with the pestilence; and I will make them into a trembling for all the kingdoms of the earth, for a curse and for a desolation, and for astonishment and for shame among all the nations whither I have made them go into exile” (italics original). See Robert Hayward, trans., The Targum of Jeremiah: Translated, with a Critical Introduction, Apparatus, and Notes (Aramaic Bible 12; Wilmington, Del.: Michael Glazier, 1987), 126. ↩

- See Charles, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Revelation of St. John, 1:160. ↩

- See Hawkins, 22. Jeremias (Parables, 100 n. 42) noted that, in comparison to the high frequency of τε in Acts (151xx), the fact that there are only nine instances of τε in the Gospel of Luke (Luke 2:16; 12:45; 14:26; 15:2; 21:11 [2xx]; 22:66; 23:12; 24:20) demonstrates the author of Luke’s editorial restraint in his treatment of his sources. Cf. Randall Buth, “Evaluating Luke’s Unnatural Greek: A Look at His Connectives,” in Discourse Studies and Biblical Interpretation: A Festschrift in Honor of Stephen H. Levinsohn (ed. Steven E. Runge; Bellingham, Wash.: Logos Bible Software, 2011), 335-369, esp. 339-341. Nevertheless, the frequency of τε in Luke’s Gospel is high in comparison to Mark (0xx) and Matthew (3xx; Matt. 22:10; 27:48; 28:12). There is no agreement among the Synoptic Gospels on the use of τε. See Lindsey, GCSG, 3:228. While some instances of τε in Luke may be attributable to FR, most instances are likely due to Lukan redaction. ↩

- See Cadbury, Style, 117. On the author of Luke’s redactional use of κατά + ὅλος to express “throughout,” see Possessed Man in Girgashite Territory, Comment to L144. On the author of Luke’s redactional use of κατά + πόλις, see Narrow Gate, Comment to L2. ↩

- The sequence sword→ famine→ pestilence also occurs in 4QPsalmsPesher [4Q171] II, 1. ↩

- See LSJ, 1946. ↩ ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 2:878-879. ↩

- See Dos Santos, 194. ↩

- See Even-Shoshan, Concordance, 1081-1082. ↩

- On the duration of the famine in Judea, see Daniel R. Schwartz, “Ishmael ben Phiabi and the Chronology of Provincia Judaea,” in his Studies in the Jewish Background of Christianity (Tübingen: Mohr [Siebeck], 1992), 218-242, esp. 236-237. ↩

- On the extent of the famine, see Kenneth Sperber Gapp, “The Universal Famine Under Claudius,” Harvard Theological Review 28.4 (1935): 258-265; Peter Garnsey, Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World: Responses to Risk and Crisis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 21. ↩

- See Seneca, On the Shortness of Life 18:5-6; Dio Cassius, Roman History 59:17 §2. ↩

- See Tacitus, Ann. 12:43; Suetonius, Claud. 18:2. ↩

- See Tacitus, Ann. 15:18. ↩

- See Tacitus, Ann. 15:39 §3; Suetonius, Nero 38:1. ↩

- See Tacitus, Hist. 1:73, 86, 89; 3:8, 48; 4:38, 52. On the food shortages in Rome we have mentioned, see Garnsey, Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World, 222-224. ↩

- See Garnsey, Famine and Food Supply in the Graeco-Roman World, 19. ↩

- See Creed, 255; Manson, Sayings, 326; Fitzmyer, 2:1337. For examples of the pairing of λιμός with λοιμός, see Wolter, 2:421. ↩