Updated: 24 January 2024

The Gospels of Luke and Matthew each contain a lengthy discourse unit with roughly similar content. In Luke this discourse unit is traditionally called the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6:20-7:1), while in Matthew the discourse unit is known as the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:1-7:29; 8:5a).[1]

The table below shows the pericopae that occur in both the Lukan and Matthean sermons:

| Pericope Title | Matt. | Luke |

| Beatitudes | 5:1-10 | 6:20-21, 24-26 |

| Blessings in Persecution | 5:11-12 | 6:22-23 |

| Loving Enemies | 5:38-48; 7:12 | 6:27-36 |

| Measure for Measure | 7:1-2 | 6:37-38 |

| Hypocrisy | 7:3-5 | 6:41-42 |

| Fruit of the Heart | 7:16-20 | 6:43-45 |

| Houses on Rock and Sand parable | 7:21, 24-27 | 6:46-49 |

| Sermon’s End | 7:28a; 8:5a | 7:1 |

Two notable facts about this list are 1) the pericopae the two sermons share in common occur (for the most part) in the same general sequence,[2] and 2) this list covers nearly all of Luke’s Sermon on the Plain (only A Blind Guide [Luke 6:39] and Disciple and Master [Luke 6:40] are excluded). Matthew’s sermon, on the other hand, contains considerably more than these few agreed upon pericopae.

It would be easy to assume that Luke’s Sermon on the Plain preserves the contours (if not the precise wording) of the original discourse, whereas the author of Matthew, following his usual editorial practice, drew in additional materials from elsewhere in his sources to create the Sermon on the Mount. This explanation may be partially correct. Nevertheless, two points caution against adopting this facile solution to account for all of the differences between the two sermons. First, the Sermon on the Plain is not fully coherent. Luke’s sermon lacks thematic unity. Either the Sermon on the Plain is composite (built of originally disparate materials) or incomplete (missing pieces that would have given the sermon coherence), or, as we suspect, it is simultaneously composite and incomplete (i.e., an editor has both added some materials and omitted others). Second, for various reasons Lindsey believed that Luke’s Sermon on the Plain was copied not from the Anthology (the more ancient, more extensive and more Hebraic of Luke’s two main sources) but from the First Reconstruction (an epitome of the Anthology with improved Greek style).[3] It would have been in accordance with the First Reconstructor’s editorial approach to have presented a pared-down version of the Anthology’s (Anth.’s) sermon that included only those sayings that were deemed pertinent to a mixed audience of Jewish and Gentile believers.[4] In that case, Luke’s Sermon on the Plain is unlikely to contain the entirety of the original sermon. Since the core of Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount was inherited from Anth., the source of all Matthew’s Double Tradition (DT) pericopae, it is possible that a more complete version of the original sermon remains embedded in Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount.

Matthew’s Additions to Anth.’s Sermon

One way to determine which pericopae in the Sermon on the Mount the author of Matthew pulled in from other sources, and which are original to the pre-synoptic homily he found in Anth., is to identify which pericopae have parallels in Mark or in Luke outside the Sermon on the Plain. Such pericopae probably owe their presence in the Sermon on the Mount to the author of Matthew’s redactional activity.[5] Pericopae in the Sermon on the Mount that do not have parallels in Mark or Luke are more likely to have belonged to the pre-synoptic homily.

The table below shows all of the pericopae in the Sermon on the Mount and indicates which have parallels in Mark and in Luke outside the Sermon on the Plain:

| Sermon on the Mount | Matthew | Mark | Luke |

| 5:1-10 Beatitudes | |||

| 5:11-12 Blessings in Persecution | |||

| 5:13 Savory Salt | Mark 9:49-50 | Luke 14:34-35 | |

| 5:14-16 Hiding a Lamp | Luke 11:33 | ||

| Mark 4:21 | Luke 8:16 | ||

| 5:17-18 Heaven and Earth Pass Away | Luke 16:17 | ||

| Matt. 24:35 | Mark 13:31 | Luke 21:33 | |

| 5:19 Doing and Teaching the Commandments | |||

| 5:20 More Righteous than the Scribes and Pharisees | |||

| 5:21-22 Murder | |||

| 5:23-24 Approaching the Altar | Mark 11:25a[6] | ||

| 5:25-26 Settle out of Court | Luke 12:57-59 | ||

| 5:27-28 Adultery | |||

| 5:29-30 Show Yourself No Mercy | Matt. 18:8-9 | Mark 9:43-48 | |

| 5:31-32 Divorce | Matt. 19:1-9 | Mark 10:1-12 | Luke 16:18 |

| 5:33-37 Swearing | |||

| 5:38-48 Loving Enemies | |||

| 6:1-4 Almsgiving | |||

| 6:5-6 Prayer | |||

| 6:7-8 Praying Like Gentiles | |||

| 6:9-15 Lord’s Prayer | Mark 11:25 | Luke 11:1-4 | |

| 6:16-18 Fasting | |||

| 6:19-21 Treasure in Heaven | Luke 12:33-34 | ||

| 6:22-23 A Good Eye | Luke 11:34-36 | ||

| 6:24 Serving Two Masters | Luke 16:13 | ||

| 6:25-34 Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry | Luke 12:22-31 | ||

| 7:1-2 Measure for Measure | |||

| 7:3-5 Hypocrisy | |||

| 7:6 Profaning the Holy | |||

| 7:7-8 Friend in Need simile | Luke 11:5-10 | ||

| 7:9-11 Fathers Give Good Gifts simile | Luke 11:11-13 | ||

| 7:12 Loving Enemies | |||

| 7:13-14 Narrow Gate | Luke 13:22-24 | ||

| 7:15 Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing | |||

| 7:16-20 Fruit of the Heart | |||

| 7:21 Houses on Rock and Sand parable | |||

| 7:22-23 Closed Door | Luke 13:25-27 | ||

| 7:24-27 Houses on Rock and Sand parable | |||

| 7:28a Sermon’s End |

| Key: Blue = pericope occurs in the Sermon on the Mount (SM) and the Sermon on the Plain (SP); Pink = SM pericope with parallel in Mark or in Luke outside SP |

Having Markan and/or Lukan parallels from outside the Sermon on the Plain is a fairly good indicator that the author of Matthew drew the pericope into the Sermon on the Mount from elsewhere in his sources, but two cases deserve additional scrutiny because the Lukan parallels are found in a collection we call a “string of pearls.” The Lukan “strings of pearls” are made up of three or four discrete sayings that were grouped together either because of a catchword or a theme. We have identified the First Reconstruction (FR) as Luke’s source for the “strings of pearls.” Because the First Reconstructor drew these sayings out of their original contexts in order to string them together, a “string of pearls” saying carries less weight against its inclusion in the Sermon on the Mount than other Lukan or Markan sayings.

Detail of a Fayum mummy portrait (ca. 140 C.E.) of a wealthy woman wearing a string of pearls. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The first pericope in the Sermon on the Mount with a “string of pearls” parallel is Heaven and Earth Pass Away. There are Double Tradition (DT) and Triple Tradition (TT) versions of this particular saying. Luke’s DT version is the one that appears in a “string of pearls” (Luke 16:17). Like the version in the Sermon on the Mount, it concerns the continuing validity of the Law. The TT versions are quite different: they are not concerned with the Law but with Jesus’ words. The TT versions appear in Jesus’ eschatological discourse as an affirmation of the prophecies attributed to Jesus. As we discuss elsewhere, we believe the TT version of Heaven and Earth Pass Away is not an authentic saying of Jesus.[7] It was adapted from the DT version to serve as the First Reconstructor’s conclusion to his expanded and updated version of the eschatological discourse. Since we know the “string of pearls” was not the original context of Luke’s DT version of Heaven and Earth Pass Away, it is possible that the context in which Matthew preserves the DT version of this pericope is, in fact, original.

The second pericope in the Sermon on the Mount with a “string of pearls” parallel is the pericope on Divorce (Matt. 5:31-32 ∥ Luke 16:18). This pericope has no doublets in Luke, but it is paralleled in Mark 10:11-12 and Matt. 19:9. There, Jesus’ ruling on divorce is embedded in a longer teaching narrative (Mark 10:1-12 ∥ Matt. 19:1-9), where it appears to be original. Luke’s “string of pearls” saying dealing with divorce was probably extracted from this longer narrative. The author of Matthew probably imported Jesus’ ruling on divorce into the Sermon on the Mount because it concerns the problem of adultery, a subject that is also dealt with in Matt. 5:27-28.

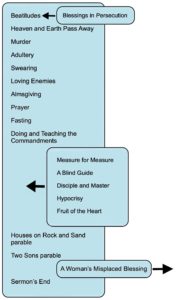

When we eliminate the pericopae that are most likely to have been drawn into the Sermon on the Mount on the grounds that they have parallels in Mark and/or outside the Sermon on the Plain in Luke (with the exception of Heaven and Earth Pass Away, for the reasons we have already discussed), the result is as follows:

| Pericope Title | Matt. | Luke |

| Beatitudes | 5:1-10 | 6:20-21, 24-26 |

| Blessings in Persecution | 5:11-12 | 6:22-23 |

| Heaven and Earth Pass Away | 5:17-18 | 16:17 |

| Doing and Teaching the Commandments | 5:19 | |

| More Righteous than the Scribes and Pharisees | 5:20 | |

| Murder | 5:21-22 | |

| Adultery | 5:27-28 | |

| Swearing | 5:33-37 | |

| Loving Enemies | 5:38-48; 7:12 | 6:27-36 |

| Almsgiving | 6:1-4 | |

| Prayer | 6:5-6 | |

| Praying Like Gentiles | 6:7-8 | |

| Fasting | 6:16-18 | |

| Measure for Measure | 7:1-2 | 6:37-38 |

| Hypocrisy | 7:3-5 | 6:41-42 |

| Profaning the Holy | 7:6 | |

| Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing | 7:15 | |

| Fruit of the Heart | 7:16-20 | 6:43-45 |

| Houses on Rock and Sand parable | 7:21, 24-27 | 6:46-49 |

| Sermon’s End | 7:28a; 8:5a | 7:1 |

| Key: Blue = pericope occurs in the Sermon on the Mount (SM) and the Sermon on the Plain (SP); Pink = SM pericope with parallel in Mark or Luke outside SP |

When we look at the result of this culled sermon, an inner coherence already begins to emerge. The sermon is concerned with the Torah and the commandments. Several of the most serious negative commandments (i.e., prohibitions, viz. murder, sexual transgression, bearing false witness)[8] and several of the more prominent positive commandments (viz. love, almsgiving, prayer, fasting) are couched in more general exhortations to live ethically in keeping with the moral vision revealed in the Torah. Moreover, our provisional retention of Heaven and Earth Pass Away is further validated by the emergence of this thematic unity. In Heaven and Earth Pass Away Jesus affirms the perpetual validity of the Torah, a sentiment that fits nicely within this larger collection of sayings dealing with specific commandments. The same pericope also defines the approach Jesus adopts toward the commandments he discusses later in the sermon: in Matt. 5:17 Jesus adopts exegetical terminology also attested in rabbinic literature when he states that he has not come to nullify the Torah but to establish it, not in the ultimate sense of causing the Torah to stand or fall, but in the midrashic sense of interpreting the Torah correctly in order to bring out its fullest meaning and truest intentions.[9] Then, in his interpretations of the commandments Jesus rejects minimalistic approaches to the commandments that reduce them to the narrowest possible application, and adopts instead a maximalist approach that broadens the commandments to their widest possible extent.[10] Thus, for example, Jesus broadened the prohibition against murder to warn against anger, he broadened the prohibition against adultery to warn against lecherous desire, he widened the command to love one’s neighbor to include a mandate to love one’s enemy. Likewise, Jesus insisted that the performance of mitzvot (good deeds, viz. almsgiving, prayer, fasting) is not to be done for the sake of appearance to win approval from fellow human beings, but from pure motives as acts of devotion toward God.

Moses receiving the Torah on Sinai as depicted in an illuminated manuscript (ca. 840 C.E.). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Nevertheless, simply because a pericope in the Sermon on the Mount has no Markan or Lukan parallel outside the Sermon on the Plain, this is no guarantee that the pericope is original to Anth.’s homily. The author of Matthew could have drawn some of these sayings into the Sermon on the Mount from elsewhere in Anth., or he could have composed some of these uniquely Matthean sayings himself. How, then, can possible Matthean additions be distinguished from pericopae original to the pre-synoptic sermon?

One method is to check whether these remaining pericopae contain themes and vocabulary consistent with the rest of the sermon, since this method has already proven useful for confirming that Heaven and Earth Pass Away belonged to the original sermon. So, for instance, Doing and Teaching the Commandments (Matt. 5:19) not only concerns the Torah and the commandments—the overarching theme of the sermon—it also emphasizes doing, a theme that is picked up in Houses on Rock and Sand, which is found in the Sermon on the Mount and the Sermon on the Plain. Doing and Teaching the Commandments fits the general scope of the sermon, and it can be securely anchored to a pericope that certainly occurred in the pre-synoptic sermon. It therefore seems probable that Doing and Teaching the Commandments belonged to the original sermon.

On the other hand, More Righteous than the Scribes and Pharisees (Matt. 5:20) has a polemical tone that is not characteristic of the rest of the sermon. It not merely critiques undesirable behavior such as hypocrisy, it places the readers of Matthew’s Gospel in competition with a particular brand of Judaism, that of the Pharisees. Since the Pharisees are not mentioned anywhere else in the Sermon on the Mount, and since they are a well-known target of the author of Matthew’s redactional polemics, the reference to the Pharisees stands out as a foreign element.[11] Moreover, More Righteous than the Scribes and Pharisees does not contain the motif of the Torah or the commandments, instead it refers vaguely to “righteousness,” which the author of Matthew makes no attempt to define.[12] More Righteous than the Scribes and Pharisees is therefore entirely suspect. Not only does it appear foreign to the pre-synoptic sermon, it has the appearance of a polemical composition penned by the author of Matthew himself.[13]

The same method of checking for verbal and thematic consistency can be applied to Almsgiving (Matt. 6:1-4), Prayer (Matt. 6:5-6) and Fasting (Matt. 6:16-18), each of which contain the motif of receiving a wage (μισθός) either from God or from human beings. The wage motif also occurs in both the Matthean (Matt. 5:46) and the Lukan (Luke 6:35) versions of Loving Enemies (Matt. 5:38-48 ∥ Luke 6:27-36). Since Loving Enemies occurs in both the Sermon on the Mount and the Sermon on the Plain, it probably belongs to the original sermon, and since the wage motif in Almsgiving, Prayer and Fasting appears to be integral to these pericopae (i.e, it does not appear to have been introduced by the author of Matthew), these pericopae may well belong to the original sermon. Moreover, almsgiving, prayer and fasting are three of the most prominent positive commandments, and for that reason, too, they are at home in a sermon that deals with the Torah and the commandments.

The same method of checking for verbal and thematic consistency can be applied to Almsgiving (Matt. 6:1-4), Prayer (Matt. 6:5-6) and Fasting (Matt. 6:16-18), each of which contain the motif of receiving a wage (μισθός) either from God or from human beings. The wage motif also occurs in both the Matthean (Matt. 5:46) and the Lukan (Luke 6:35) versions of Loving Enemies (Matt. 5:38-48 ∥ Luke 6:27-36). Since Loving Enemies occurs in both the Sermon on the Mount and the Sermon on the Plain, it probably belongs to the original sermon, and since the wage motif in Almsgiving, Prayer and Fasting appears to be integral to these pericopae (i.e, it does not appear to have been introduced by the author of Matthew), these pericopae may well belong to the original sermon. Moreover, almsgiving, prayer and fasting are three of the most prominent positive commandments, and for that reason, too, they are at home in a sermon that deals with the Torah and the commandments.

Praying Like Gentiles (Matt. 6:7-8), on the other hand, does not contain the wage motif. It also stands out from the other pericopae relating to positive commandments in that it lacks the motif of hypocrisy, which is present in Almsgiving, Prayer and Fasting. Moreover, whereas Almsgiving, Prayer and Fasting critique the ostentatious behavior of fellow Jews, Praying Like Gentiles cites the behavior of non-Jews as a negative example. It appears, therefore, that Praying Like Gentiles did not belong to the original sermon. The author of Matthew incorporated Praying Like Gentiles into the Sermon on the Mount because its subject is prayer.[14]

Profaning the Holy (Matt. 7:6) does not relate to the Torah or the commandments, but it does reflect a concern that sacrifices (“the holy thing”) not be profaned by being consumed by dogs, an impure animal, a concern which is found in other ancient Jewish sources.[15] Therefore, this saying might have come from Jesus, but it probably did not belong to the original sermon on the Torah and the commandments. Whether it was added by the author of Matthew or by the Anthologizer before him may be impossible to decide.

Easier to determine is Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing (Matt. 7:15), which introduces the author of Matthew’s redactional polemic against false Christian prophets, a subject that occupies much of the concluding section of the Sermon on the Mount and which the author of Matthew took great pains to introduce into his versions of Fruit of the Heart (Matt. 7:16-20)[16] and Houses on Rock and Sand (Matt. 7:21-27).[17] As such, Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing may be entirely redactional,[18] and in any case is not original to the pre-synoptic sermon.[19] The author of Matthew’s use of animal imagery in Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing may hint that he was responsible for inserting Profaning the Holy (which mentions dogs and pigs), but this is not certain.

Having used all these methods to whittle away the Matthean additions, we suggest that Anth.’s version of the sermon looked like this:

| Pericope Title | Matt. | Luke |

| Beatitudes | 5:1-10 | 6:20-21, 24-26 |

| Blessings in Persecution | 5:11-12 | 6:22-23 |

| Heaven and Earth Pass Away | 5:17-18 | 16:17 |

| Doing and Teaching the Commandments | 5:19 | |

| Murder | 5:21-22 | |

| Adultery | 5:27-28 | |

| Swearing | 5:33-37 | |

| Loving Enemies | 5:38-48; 7:12 | 6:27-36 |

| Almsgiving | 6:1-4 | |

| Prayer | 6:5-6 | |

| Fasting | 6:16-18 | |

| Measure for Measure | 7:1-2 | 6:37-38 |

| A Blind Guide | 15:14 | 6:39 |

| Disciple and Master | 10:24-25a | 6:40 |

| Hypocrisy | 7:3-5 | 6:41-42 |

| Fruit of the Heart | 7:16-20 | 6:43-45 |

| Houses on Rock and Sand parable | 7:21, 24-27 | 6:46-49 |

| Two Sons parable | 21:28-31a | |

| Sermon’s End | 7:28a; 8:5a | 7:1 |

| Key: Blue = pericope occurs in the Sermon on the Mount (SM) and the Sermon on the Plain (SP); Pink = SM pericope with parallel in Mark or Luke outside SP; Cream = pericope removed from SM by Matthew and from SP by the First Reconstructor; Green = pericope in SP Matthew removed from SM |

It will be noticed that in our reconstruction of Anth.’s version of the sermon we have reinserted two pericopae that appear in Luke’s Sermon on the Plain: A Blind Guide (Luke 6:39) and Disciple and Master (Luke 6:40). These we have marked in green. This has been necessary for two reasons. First, the First Reconstructor’s approach to the sermon was to trim away some of Anth.’s sayings, not to add to the sermon. Second, neither of the contexts in which Matthean parallels occur in Matthew appear to be original.[20] Therefore, it is at least probable that these two pericopae were included in Anth.’s version of the sermon.[21]

We have also included the Two Sons parable (Matt. 21:28-31a), which we have marked in a cream color, in Anth.’s sermon for the following reasons:

First, the message of the Two Sons parable is very similar to the message of Houses on Rock and Sand,[22] for it, too, emphasizes the importance of doing over mere assent, and in it a son addresses his father as “Lord,” but fails to do what his father asked (cf. the introduction to Houses on Rock and Sand [“Why do you call me ‘Lord! Lord!’ but you do not do what I say?”]). It is therefore possible that the Two Sons parable was paired with Houses on Rock and Sand in the original sermon. This supposition would fit with Lindsey’s belief that most of Jesus’ teaching discourses in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua concluded with dual illustrations, often twin parables. Houses on Rock and Sand and Two Sons are not similar enough to be classified as twins,[23] but their messages are close enough to have served as complimentary concluding illustrations.

Second, it was not usual for the Anthologizer to separate twin parables,[24] and therefore it is reasonable to expect that he would not have separated these dual illustrations (Houses on Rock and Sand and Two Sons) either.

Third, Matthew’s context for the Two Sons parable does not appear to be original. The author of Matthew made the Two Sons parable a continuation of Jesus’ response to Questioning Yeshua’s Authority (Matt. 21:23-27; Mark 11:27-33; Luke 20:1-8), but the argument is not logical (What does the Two Sons parable prove about Jesus’ authority?), and nothing corresponding to Two Sons appears in Mark or Luke. The author of Matthew uses the Two Sons parable to introduce a polemic against Jesus’ interlocutors for not believing in John the Baptist, who came in “the way of righteousness” (Matt. 21:32), claiming that tax collectors and sex workers—who did believe John’s message—are going into the Kingdom of God ahead of them (Matt. 21:31b). This passage bears several marks of Matthean redaction. It refers to the Kingdom of God instead of using the Hebraic term Kingdom of Heaven, it connects John the Baptist’s proclamation with the Kingdom, a connection that is only found in the Gospel of Matthew (Matt. 3:2),[25] and it contains Matthew’s vague notion of “righteousness,” which we have already mentioned.[26] Thus it appears the author of Matthew took the Two Sons parable from some other context in Anth. in order to make it serve his redactional interests.

Fourth, there may be a clue that the author of Matthew knew that Two Sons had once been connected to Houses on Rock and Sand. What clue is this? Jesus concludes the Two Sons parable by asking his audience which of the two sons—the one who assented but failed to act, or the one who did not initially accede to his father’s request but then changed his mind and acted accordingly—did the will of the father (ἐποίησεν τὸ θέλημα τοῦ πατρός; Matt. 21:31). The wording of Jesus’ question in the Two Sons parable is quite similar to Jesus’ statement at the opening of Matthew’s version of Houses on Rock and Sand, where the author of Matthew has Jesus state, “Not everyone who calls me ‘Lord! Lord!’ will enter the Kingdom of Heaven, but the one who does the will of my father in heaven (ὁ ποιῶν τὸ θέλημα τοῦ πατρός μου τοῦ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς)” (Matt. 7:21). For reasons we discuss at length in Houses on Rock and Sand,[27] we do not believe Matthew’s wording of this statement is original.[28] It may be, however, that Matthew’s wording was inspired by Jesus’ question in the Two Sons parable, where the father in question is not the Heavenly Father but the father of the two sons in the parable. Such interference between pericopae that the author of Matthew knew or believed to be related is so typical of his editorial style that we have given it a name, Matthean cross-pollination. The influence of Jesus’ question in the Two Sons parable on the Matthean form of the introduction to Houses on Rock and Sand is therefore an important clue that the author of Matthew knew that Houses on Rock and Sand and Two Sons had once been connected.

Finally, the only way the author of Matthew could have known that these two pericopae had once been connected is if it was he himself who had separated them. We noted before that it appears that the author of Matthew took Two Sons from some other context in Anth. in order to insert it into the controversies between Jesus and the authorities in the Temple. Now we can say with some justification that the Anth. context from which the author of Matthew took the Two Sons parable was the pre-synoptic version of the sermon that stands behind the Sermon on the Mount and (via FR) the Sermon on the Plain.

The Anthology’s Additions to the Original Sermon

Even Anth.’s version of the sermon likely contained some sayings that originally belonged to other contexts. For instance, the beatitude on persecution, Blessings in Persecution (Matt. 5:11-12 ∥ Luke 6:22-23), is different in form and content from the preceding beatitudes—it is the only beatitude in the Sermon on the Mount / Sermon on the Plain in which a blessing is contingent upon personal commitment to Jesus—and so was likely added to the original collection of beatitudes by the Anthologizer.[29]

Likewise, neither Measure for Measure, nor A Blind Guide, nor Disciple and Master, nor Hypocrisy, nor Fruit of the Heart are concerned with the Torah or the commandments. We think it is likely, therefore, that the Anthologizer added these pericopae to the original sermon. It is possible that he combined the original sermon on the Torah and the commandments with another sermon on true and false discipleship to produce the sermon that formed the core of the Sermon on the Mount and that stands behind the Sermon on the Plain.

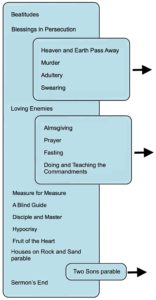

The Sermon in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua

We believe that the sermon on the Torah and the commandments contained in the Hebrew Life of Yeshua may have looked like this:

Aside from omitting the pericopae we have identified as Anth. additions, we have moved Doing and Teaching the Commandments to a location near the end of the sermon from its Matthean position toward the beginning.[30] We believe this location makes more sense as a reflection back on the sermon (for otherwise, to what do “these commandments” in Matt. 5:19 refer?),[31] and with its emphasis on doing it ties in well with the Houses on Rock and Sand parable. Whether it was the Anthologizer or the author of Matthew who relocated Doing and Teaching the Commandments is impossible to tell, but we suspect it was the author of Matthew.

We have also included A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing as a narrative epilogue to the sermon. Jesus’ message in A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing is similar to the message of Houses on Rock and Sand in as much as they both concern hearing and doing.[32] It is true that Houses on Rock and Sand stresses the importance of not only hearing Jesus’ word but also doing what he said, whereas A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing stresses the importance of hearing God’s word and doing it. However, this contrast should not be exaggerated, since Jesus, like other Jewish sages, regarded his teaching as part of the living Torah, not as distinct from or opposed to it.[33] Therefore, we can imagine Jesus emphasizing his interpretation of the Torah in Houses on Rock and Sand at the end of his sermon, but stressing the importance of doing the word of God in A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing after the sermon had concluded. Our placement of A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing is by no means certain, but no better alternative has yet presented itself. Our inclusion of A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing in this narrative-sayings complex also has this in its favor: it is consistent with the Anthologizer’s practice of separating narratives and sayings from one another. And as an epilogue to the sermon it creates a pleasing inclusio by pronouncing a beatitude (“Blessed are those who hear the word of God and do it”), which harks back to the beatitudes with which the sermon began.[34]

The advantage of this arrangement in a narrative-sayings complex we refer to as the “Torah and the Kingdom of Heaven” complex is that it presents Jesus’ outlining a positive vision of the fulfillment of the Torah according to the halachah of the Kingdom of Heaven (Beatitudes); it sets out Jesus’ approach to the Torah (Heaven and Earth Pass Away), according to which even the least stroke of a pen will be taken into account so as to live out the Torah’s deepest intentions; it then contrasts Jesus’ vision with competing interpretations of the Torah (Murder, Adultery, Swearing, Loving Enemies) and inadequate performance of the commandments (Almsgiving, Prayer, Fasting) while also detailing Jesus’ positive vision (do not merely keep the commandments, live out their true intentions); it affirms that those who do and teach the commandments according to Jesus’ halachic instruction will be great in the Kingdom of Heaven (Doing and Teaching the Commandments); and it concludes with two illustrations and an epilogue (Houses on Rock and Sand, Two Sons, A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing) that make the point that it is following Jesus’ halachah, not flattering him with praise, that counts.

Click on the following titles to view the Reconstruction and Commentary for each pericope in the “Torah and the Kingdom of Heaven” complex.

Yeshua Attends to the Crowds (In Preparation!)

Yeshua Attends to the Crowds (In Preparation!)

Beatitudes

Beatitudes

Murder

Murder

Adultery

Adultery

Swearing

Swearing

Loving Enemies

Loving Enemies

Almsgiving

Almsgiving

Prayer

Prayer

Fasting

Fasting

Doing and Teaching the Commandments

Doing and Teaching the Commandments

Houses on Rock and Sand parable (Newly Published!)

Houses on Rock and Sand parable (Newly Published!)

Two Sons parable (In Preparation!)

Two Sons parable (In Preparation!)

Sermon’s End (Recently Published!)

Sermon’s End (Recently Published!)

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

- [1] For abbreviations and bibliographical references, see “Introduction to ‘The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction.’” ↩

- [2] The exception is the placement of the Golden Rule (Matt. 7:12 ∥ Luke 6:31), which in Luke forms part of the Loving Enemies pericope (Luke 6:27-36), but occurs separately in Matthew. We believe it was the author of Matthew who separated the Golden Rule from its original context in order to form an inclusio referring to the Law and the Prophets at the beginning (Matt. 5:17) and end (Matt. 7:12) of the main didactic section of the Sermon on the Mount. Cf. Vincent Taylor, “The Original Order of Q,” in New Testament Essays: Studies in Memory of Thomas Walter Manson (ed. A. J. B. Higgins; Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959), 246-269, esp. 250-251; Strecker, 151; Sandt-Flusser, 198-199. ↩

- [3] Lindsey’s reasons for attributing the Sermon on the Plain to the First Reconstruction (FR) include the low levels of verbal agreement between the Lukan and Matthean parallels belonging to the two sermons, and the more Hebraic Greek in Matthew’s versions compared to the stylistically better Greek of Luke’s versions. ↩

- [4] Meanwhile, it would have been in accordance with the Anthologizer’s editorial approach to have inserted thematically related sayings (e.g., the beatitude on persecution [Matt. 5:11-12 ∥ Luke 6:22-23] at the end of the original collection of beatitudes) into the original sermon. Since the First Reconstructor was unlikely to have removed from the sermon all of the sayings the Anthologizer had added, the resulting Sermon on the Plain in Luke is both composite (due to Anth.’s additions) and incomplete (because of FR’s deletions). ↩

- [5] Cf. Sandt-Flusser, 204. ↩

- [6] See Lord’s Prayer, Comment to L27. ↩

- [7] See Heaven and Earth Pass Away, under the “Conjectured Stages of Transmission” subheading. ↩

- [8] It is often suggested that the organization of these prohibitions reflects the second table of the Ten Commandments, but we are unsure of this. The transgressions mentioned in the Sermon on the Mount are similar to the list of three sins which a pious Jew must never commit even at pain of death (viz. idolatry, bloodshed, sexual transgression). Occasionally the “evil tongue” is mentioned as being as serious as these three transgressions. By “evil tongue” slander is usually meant, but one could see how bearing false witness could fit in this category. These major transgressions are similar to the early list of prohibitions enjoined on the descendants of Noah and the list of transgressions that ought to have been obvious, even if they had not been written in the Torah. Likewise, these prohibitions are similar to the description of the “Way of Death” in the Two Ways tradition. ↩

- [9] See David Flusser, “Die Tora in der Bergpredigt,” in Juden und Christen lesen dieselbe Bibel (ed. Heinz Kremers; Duisburg: Braun, 1973), 102-113. For an English translation of this article on WholeStones.org, entitled “The Torah in the Sermon on the Mount,” click here. On Jesus’ use of exegetical terminology in Matt. 5:17, see especially “The Torah in the Sermon on the Mount,” under the subheading “Interpreting the Torah: Abolish or Fulfill, Undergird or Undermine.” ↩

- [10] Cf. David Flusser, “‘It Is Said to the Elders’: On the Interpretation of the So-called Antitheses in the Sermon on the Mount,” under the subheading “‘The Elders’ and Pharisaic Interpretation of Scripture.” ↩

- [11] Cf. Flusser, “The Torah in the Sermon on the Mount,” n. 13. ↩

- [12] This vague use of “righteousness” is similar to Jesus’ insistence in a uniquely Matthean and almost certainly redactional passage that he must be baptized by John the Baptist “in order to fulfill all righteousness” (Matt. 3:15). On this redactional passage, see Yeshua’s Immersion, Comment to L12-22. ↩

- [13] Cf. Sandt-Flusser, 205, 224. ↩

- [14] For further discussion, see Praying Like Gentiles, under the subheading “Story Placement.” ↩

- [15] See Huub van de Sandt, “‘Do Not Give What Is Holy to the Dogs’ (Did 9:5d and Matt 7:6a): The Eucharistic Food of the Didache in its Jewish Purity Setting,” in Vigiliae Christianae 56 (2002): 223-246, esp. 230-231, 233-238; idem, “The Didache and its Relevance for Understanding the Gospel of Matthew,” under the subheading “2.2. Matthew in Light of Didache 7-16: Two Examples.” ↩

- [16] Cf. Davies-Allison, 1:694. ↩

- [17] See our discussion in Houses on Rock and Sand, under the subheading “Story Placement.” ↩

- [18] Cf. Schweizer, 177; Davies-Allison, 1:703-705; Luz, 1:375. ↩

- [19] A parallel to Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing is found in the Didache, which warns that in the end time sheep will be turned into wolves (Did. 16:3). Since it is likely that the Didache and the Gospel of Matthew emerged from the same milieu, it may be that Wolves in Sheep’s Clothing reflects the concerns of the Matthean community rather than an authentic saying of Jesus. Cf. Catchpole, 40. ↩

- [20] The author of Matthew incorporated A Blind Guide (Matt. 15:14) into True Source of Impurity (Matt. 15:1-20), which he adapted from Mark 7:1-23 and turned into a polemic against the Pharisees. Both the interpolation of smaller pericopae into larger ones and polemicizing against the Pharisees are typical of Matthean redaction. On the author of Matthew’s use of interpolation as a redactional method, see Sermon’s End, Comment to L5-7. Similarly, it appears that the author of Matthew inserted his version of Disciple and Master (Matt. 10:24-25) into the Sending the Twelve discourse in order to serve as a warning against the Pharisees (“If they called the householder Beelzeboul, how much more the members of his household?”), since in Matt. 12:24—but not in Mark 3:22 (scribes) or Luke 11:15 (some members of the crowd)—it was the Pharisees who accused Jesus of being an agent of Beelzeboul. Note that Luke’s version of Disciple and Master (Luke 6:40) does not include a polemical warning. ↩

- [21] Cf. Taylor, “The Original Order of Q,” 254-255. ↩

- [22] Cf. Snodgrass, 332. ↩

- [23] See LOY Excursus: Criteria for Identifying Separated Twin Parables and Similes in the Synoptic Gospels. ↩

- [24] We credited the author of Luke with separating Persistent Widow from Friend in Need, and the author of Matthew with separating Lost Coin from Lost Sheep, and he was probably also responsible for separating Bad Fish Among the Good from Darnel Among the Wheat. ↩

- [25] See A Voice Crying, Comment to L37-38. ↩

- [26] If Matt. 21:31b-32 is not a pure Matthean composition—the loose parallel with Luke 7:29-30 suggests it may not be—it was certainly subjected to heavy Matthean redaction. Cf. our comments on Pharisees Reject God’s Purpose (Luke 7:29-30) in the introduction to the “Yohanan the Immerser and the Kingdom of Heaven” complex. ↩

- [27] See Houses on Rock and Sand, Comment to L4-5 and Comment to L6-8. ↩

- [28] In a nutshell, there is a disconnect between calling Jesus “Lord” and entering the Kingdom of Heaven. Nowhere else in Jesus’ teaching is entering the Kingdom of Heaven contingent upon confessing him as Lord. By contrast, in Luke’s parallel, in which Jesus asks, “Why do you call me ‘Lord! Lord!’ but you do not do what I say?” (Luke 6:46), there is a logical connection between a person’s calling Jesus “Lord” and Jesus’ expectation of that person’s obedience: Lords expect the people to whom they give orders to follow them. ↩

- [29] Cf. Robert L. Lindsey, “The Hebrew Life of Jesus,” under the subheading “The Two Versions of the Beatitudes.” ↩

- [30] Cf. Kilpatrick, 25-26. Kilpatrick, however, suggested placing Doing and Teaching the Commandments after the treatment of the section mainly focused on prohibitions, whereas we place Doing and Teaching the Commandments after the treatment of the positive mitzvot. ↩

- [31] Cf. Kilpatrick, 17. For a different view, see Sandt-Flusser, 219. ↩

- [32] See Brad Young and David Flusser, “Messianic Blessings in Jewish and Christian Texts” (Flusser, JOC, 280-300, esp. 300). Cf. Manson, Sayings, 88. ↩

- [33] See Houses on Rock and Sand, Comment to L24. ↩

- [34] For further discussion of our inclusion of A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing in the “Torah and the Kingdom of Heaven” complex, see A Woman’s Misplaced Blessing, under the “Story Placement” subheading. ↩