| The image featured above, intended to symbolize the Two Ways of Life and Death, which are of central importance to the Didache, was photographed by Imen Bouhajja in Ghar Elmelh, Tunisia (courtesy of Wikimedia Commons). |

How to cite this article: Huub van de Sandt, “The Didache and its Relevance for Understanding the Gospel of Matthew,” Jerusalem Perspective (2016) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/16271/].

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link:

1. The Didache

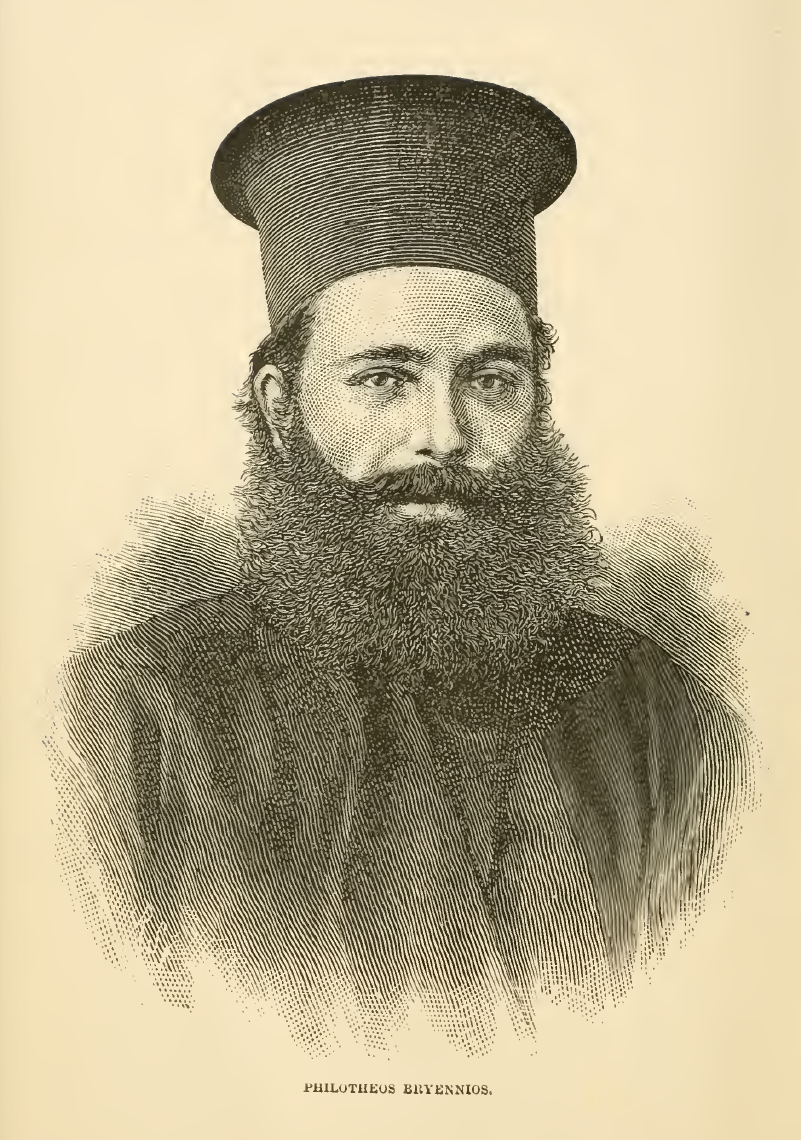

A portrait of Philotheos Bryennios found opposite the title page of Philip Schaff’s The Oldest Church Manual Called The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles (1885). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In 1873, Philotheos Bryennios, the metropolitan of Serres (Serrae) in Macedonia, discovered a Greek parchment manuscript in the monastery of the Holy Sepulchre in Constantinople. The document contained several early Christian writings, including the text of the famous Didache. Bryennios edited the treatise in 1883. In 1887, the manuscript was transferred to the Greek patriarchate in Jerusalem where it is still preserved today as Hierosolymitanus 54. In the colophon of the manuscript (folium 120, front side) the name of the scribe and the date are preserved. “Leon the scribe and sinner” was the one who produced this codex, which he completed on Tuesday, 11 June 1056.

The ancient textual basis of the eleventh-century minuscule copied by Leon should be narrowed down to its central part only (fol. 39front-80back). The source of this text, extending from the Letter of Barnabas to the end of the Didache, may have originated in the patristic period.[1] In this article, the text of the Didache (fol. 76front-80back) is studied in isolation from the other works contained in the Jerusalem Manuscript. Of course, there are also a few smaller and fractional witnesses to the text of the Didache. For the establishment of the text of the Didache, however, the bearing of these fragments is meagre.

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link:

- [1] Huub van de Sandt and David Flusser, The Didache: Its Jewish Sources and its Place in Early Judaism and Christianity, (Compendia rerum iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum 3/5; Assen: Van Gorcum-Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002), 16-24. ↩