For Merle and Charlie Jewett of Alna, Maine.[1]

Revised: 24 November 2020

One aspect of the cultural context of the Gospels that is often overlooked is the role played by animals. Nevertheless, a variety of living creatures were part of the everyday experience for people in the ancient world. In this article I will explore the significance of chickens in first-century Jewish culture and the part they play in the story of Jesus.

How Far Does His Mercy Extend?

A biblical commandment seems to indicate that chickens were not part of the early Israelite experience:

כִּי יִקָּרֵא קַן־צִפֹּור לְפָנֶיךָ בַּדֶּרֶךְ בְּכָל־עֵץ אֹו עַל־הָאָרֶץ אֶפְרֹחִים אֹו בֵיצִים וְהָאֵם רֹבֶצֶת עַל־הָאֶפְרֹחִים אֹו עַל־הַבֵּיצִים לֹא־תִקַּח הָאֵם עַל־הַבָּנִים׃ שַׁלֵּחַ תְּשַׁלַּח אֶת־הָאֵם וְאֶת־הַבָּנִים תִּקַּח־לָךְ לְמַעַן יִיטַב לָךְ וְהַאֲרַכְתָּ יָמִים׃

If you meet a bird’s nest with chicks or eggs before you in the road, or in any tree, or upon the ground, and the mother is sitting on the chicks or the eggs, you must not take the mother with her children. You must send the mother away. Then you may take the children for yourself, in order that it may be well with you and that you may prolong your days. (Deut. 22:6-7)

This commandment describes coming upon a nest with eggs as a chance occurrence. Collecting eggs from domesticated chickens is therefore not within the purview of this commandment.[2] Evidently this commandment was given before the Israelites began raising chickens for meat or eggs.[3]

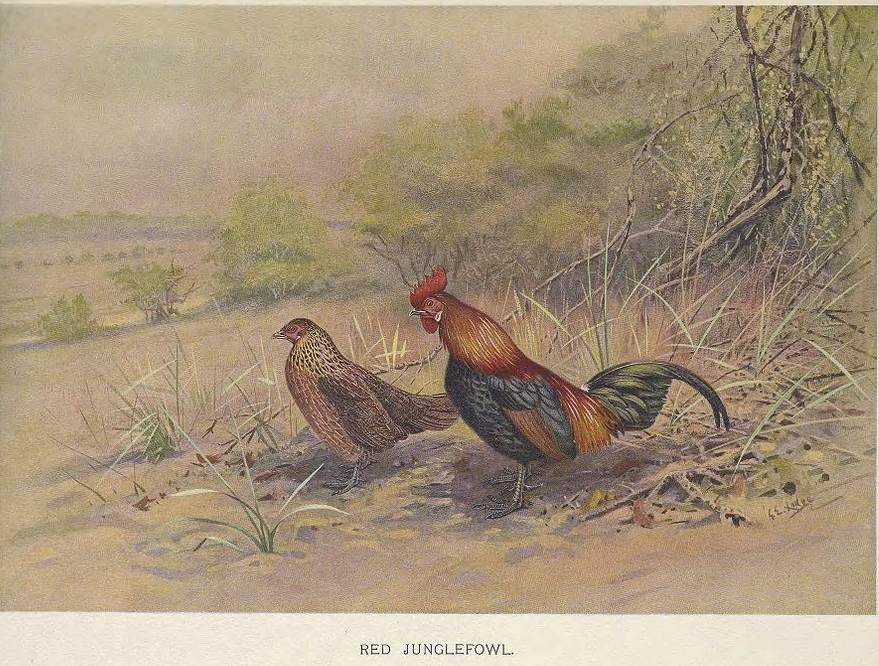

Red Jungle Fowl, the wild ancestor of the domesticated chicken, as depicted in William Beebe’s A Monograph of Pheasants (4 vols.; London: H. F. & G. Witherby, 1921), Plate 40 opposite 2:172.

It used to be assumed that chickens did not become a part of Jewish culture until after the return from exile and the rebuilding of the Temple.[4] This assumption was supported by the fact that chickens were thought not to be mentioned anywhere in the Hebrew Scriptures.

History of the Domestication of Chickens

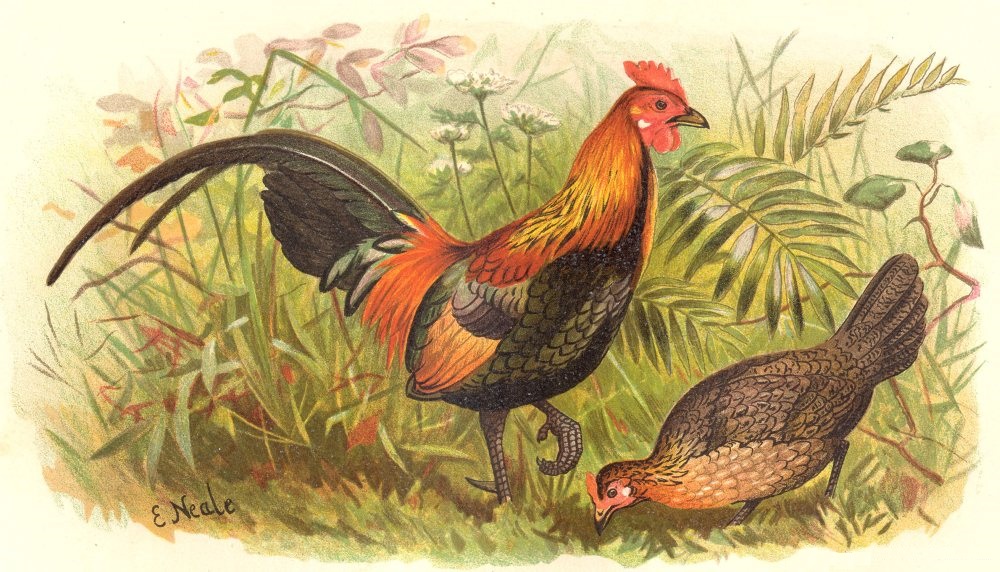

Red Junglefowl as portrayed by Edward Neale in A. O. Hume and C. H. T. Marshall, The Game Birds of India, Burmah, and Ceylon (3 vols., 1879), plate opposite 1:217. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The origin of the domesticated chicken (Gallus domesticus) is a matter of historical and scientific debate. It is certain that all chickens are descended from the Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus), which is indigenous to northern Pakistan, northern and northeastern India, Myanmar (Burma), the Yunnan province of China, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia.[5] However, there is still debate whether any of the other species of junglefowl (Grey [Sonnerat’s], Ceylon, or Green Junglefowl) also contributed to the breeding of domesticated chickens. It is also unclear exactly where chickens were domesticated, and it is even possible that there were multiple sites of independent domestication. The earliest archaeological remains of domesticated chickens, dated to approximately 5400 B.C.E., were found at Chishan in China’s Hebei province. The Hebei province of northern China is far outside the natural range of any of the species of junglefowl, and the bones discovered at Chishan are larger than those of wild junglefowl.[6] For these reasons the identification of the remains as belonging to domesticated chickens is not disputed.[7] The Chishan chicken remains point to a date of around 6000 B.C.E. for the domestication of chickens, and suggest that chickens were first domesticated in southeast Asia on the peninsula of Indochina.

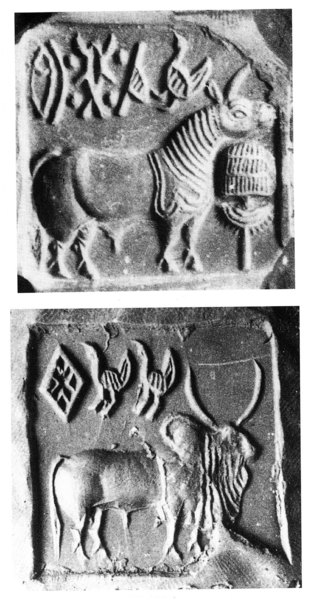

Two seals from Mohenjo-daro. Are the fowls depicted on these seals domesticated chickens? Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Another possible area of chicken domestication is in the region of the Indus River valley. Ancient seals (2500-2100 B.C.E.) that appear to depict chickens as well as the skeletal remains of chickens discovered at Mohenjo-daro suggest that chickens were kept by the people of the Indus Valley Civilization.[8] Mohenjo-daro (in today’s Pakistan) is outside the natural range of the Red Junglefowl, and therefore its presence at that site must be due to domestication.[9] It is possible that chickens were independently domesticated by the people of the Indus Valley Civilization, since Red Junglefowl do inhabit the upper reaches of the Indus River. Or it is possible that chickens were acquired by the people of the Indus Valley Civilization through trade with other peoples.[10] If chickens were independently domesticated by the people of the Indus Valley Civilization, then it is possible that the Grey Junglefowl, which is indigenous to the Indus Valley, contributed to the breeding of the domesticated chicken there.

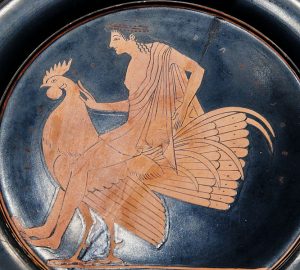

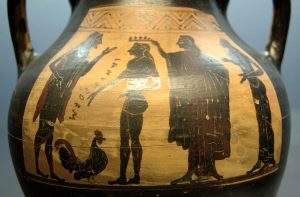

Seals bearing the images of roosters discovered at Nimrud (biblical Calah; cf. Gen. 10:11, 12) indicate that chickens were kept in Assyria by the eighth century B.C.E.[11] Chickens appear to have been introduced to the peoples along the Mediterranean coast beginning in the eighth century B.C.E.,[12] and became common throughout Greece and Asia Minor by the sixth century B.C.E.[13]

From that time depictions of roosters and hens begin to appear on everyday artifacts such as coins and pottery vessels. Chickens begin to be mentioned in Greek literature in the sixth century B.C.E.[14] The discovery of egg shells in archaeological excavations in Europe and North Africa also indicates that chickens had become an important part of daily life in this region by the middle of the first millennium B.C.E.[15]

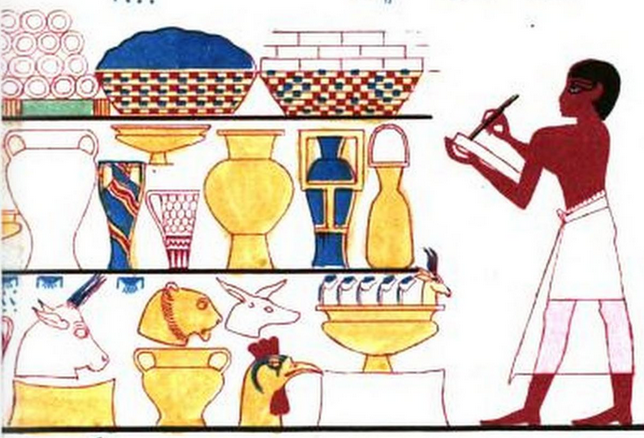

A golden rooster’s head in the bottom row of this artist’s reproduction of a painting from the tomb of Rekhamara in Thebes (ca. 1450 B.C.E.). Image from G. A. Hoskins, Travels in Ethiopia (London, 1835).

Depictions of chickens from a much earlier period have, indeed, been discovered in Egypt. Coltherd mentions graffiti on the stones of an Egyptian temple on which the names of kings from the twelfth and thirteenth dynasties appear.[16] At Thebes in upper Egypt, a mural depicting a rooster’s head was found in the tomb of Rekhamara, who was vizier to Thutmose III (ca. 1450 B.C.E.).[17] This mural depiction of a rooster may support the identification of the bird that “[gave] birth everyday” as a chicken. This bird is mentioned by Thutmose III in the Royal Annals of the Great Temple of Karnak as part of the tribute brought to the Pharaoh from a country of unknown name.[18]

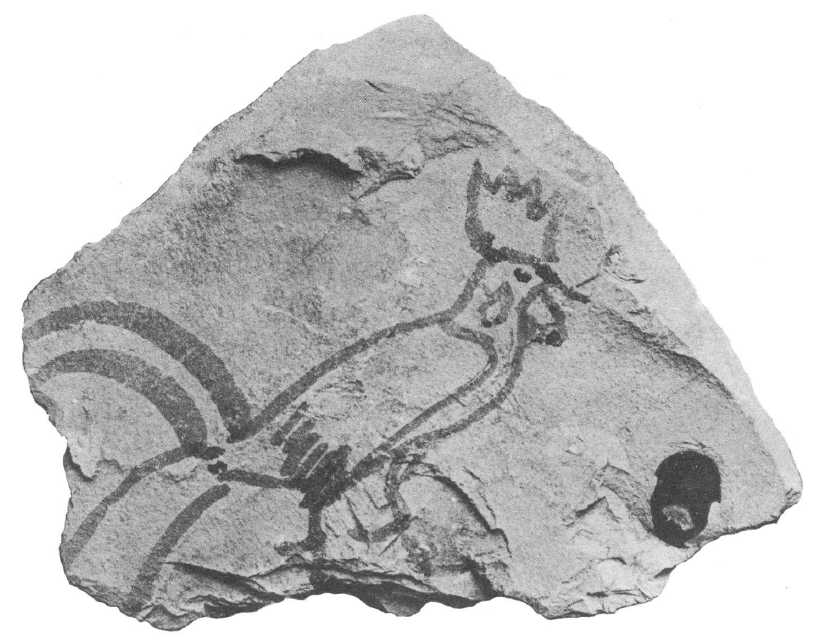

Ostracon discovered outside the tomb of Tutankhamun (ca. 1347-1338 B.C.E.) depicting a rooster. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

An ostracon found outside the tomb of Tutankhamun, and presumably dating to the time of his burial (1347-1338 B.C.E.), also clearly depicts a rooster.[19] Despite these attestations from a much earlier period, it seems that chickens did not become an established part of Egyptian daily life or spread from Egypt to other peoples along the Mediterranean. Apparently, at this early period chickens were rare and kept merely as exotic ornamental creatures, and were not raised for meat or eggs, and eventually these early chickens in Egypt faded from the scene. Only in the seventh century B.C.E., around the same time as they appeared in other places along the Mediterranean, did chickens return to Egypt as a useful animal in everyday life.[20]

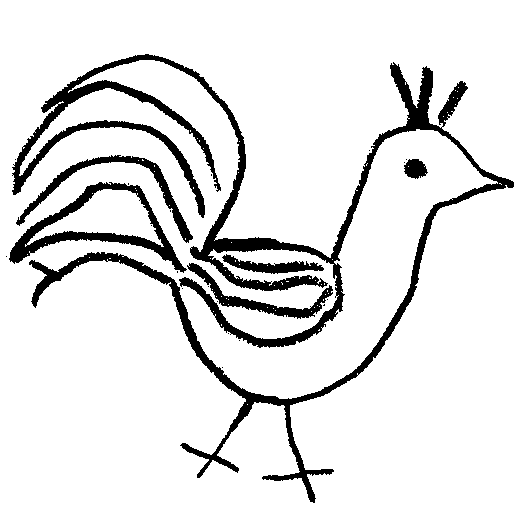

Author’s drawing of the chicken cut into the handle of a cooking pot found at Gibeon (seventh cent. B.C.E.).

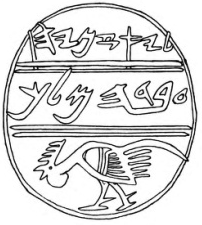

The earliest evidence for chickens in the land of Israel is in the latter part of the period of the monarchy.[21] The image of a rooster cut into the handle of a cooking pot discovered at Gibeon dates to the seventh century B.C.E.[22] Two Hebrew seals with nearly identical images of roosters have also been discovered.[23] One of the seals, made of red jasper, bears the inscription ליהואחז בן המלך (lihō’aḥaz ben hamelech, “[belonging] to Yehoahaz son of the king”). Avigad suggested two candidates who could be identified as the owner of this seal: Ahaz the son of Yotam king of Judah (who is referred to as Yehoahaz in Assyrian sources), or Yehoahaz son of king Josiah (cf. 2 Kgs. 23:30). If the seal is identified with the former, Avigad proposes the date of 733 B.C.E. for the seal; if with the latter, he suggests the date of 609 B.C.E.[24] The second seal, which Avigad dated to circa 600 B.C.E., was discovered at Tell en-Nasbeh (Mizpah). This onyx seal bears the inscription ליאזניהו עבד המלך (leya’azanyahū ‘eved hamelech, “[belonging] to Yaazanyahu the servant of the king”).[25] Identification of the seal’s owner is uncertain, but it may have belonged to an officer named יַאֲזַנְיָהוּ בֶּן הַמַּעֲכָתִי (ya’azanyāhu ben hama‘achāti, “Yaazanyahu son of the Maachatite”; 2 Kgs. 25:23),[26] who, according to 2 Kings 25:23 and Jeremiah 40:8, visited Gedaliah, the Babylonian-appointed governor of Judah, at Mizpah shortly after the fall of Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E.[27] These findings in the land of Israel correlate with the large quantities of chicken bones that were discovered in Jordan at Tell Hesban (Heshbon) dating from the seventh to sixth centuries B.C.E.,[28] and with smaller quantities of chicken bones from the Iron Age II period discovered in the City of David and the Ophel areas of Jerusalem.[29]

The biblical laws of ritual purity and kashrut (dietary laws) were no obstacle to the integration of chickens into Israelite daily life, since bird carcasses do not impart impurity and the birds forbidden for food are restricted to those enumerated in Leviticus 11:13-19 and Deuteronomy 14:11-18. All other birds were deemed to be permitted for food as we learn from a baraita in the name of Rabbi Yehudah ha-Nasi:

It was taught: Rabbi says, “It is well known to Him who spake and the world came into being that the unclean animals are more numerous than the clean, therefore did Scripture enumerate the clean. It is also well known to Him who spake and the world came into being that the clean birds are more numerous than the unclean, therefore did Scripture enumerate the unclean.” (b. Hul. 63b)[30]

Third-century B.C.E. painting from the Sidonian Tombs in Beit Guvrin. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Since the biblical laws of purity and kashrut posed no barrier, the Israelites readily accepted chickens as a source for eggs and meat once they had been introduced to the land of Israel in the latter half of the period of the monarchy.

Are Chickens Mentioned in the Hebrew Bible?

Although it is true that תַּרְנְגוֹל (tarnegōl, “rooster”) and תַּרְנְגוֹלֶת (tarnegōlet, “hen”),[31] the names given to domesticated chickens in rabbinic literature, do not occur in the Hebrew Scriptures,[32] the presence of chickens in the land of Israel in the period of the monarchy weakens the assertion that chickens are never mentioned in the Hebrew Scriptures, especially since there are ancient interpretive traditions to the contrary.[33] Most of the possible candidates appear unlikely (see prior footnote), however Proverbs 30:31 may, indeed, refer to chickens.

Proverbs 30:29-31 reads:

שְׁלֹשָׁה הֵמָּה מֵיטִיבֵי צָעַד וְאַרְבָּעָה מֵיטִבֵי לָכֶת׃

לַיִשׁ גִּבֹּור בַּבְּהֵמָה וְלֹא־יָשׁוּב מִפְּנֵי־כֹל׃

זַרְזִיר מָתְנַיִם אֹו־תָיִשׁ וּמֶלֶךְ אַלְקוּם עִמֹּו׃Three things are stately in their stride; four are stately in their gait:

the lion, which is mightiest among wild animals and does not turn back before any;

the strutting rooster [זַרְזִיר], the he-goat, and a king striding before his people. (RSV)

The Hebrew in this passage is difficult, and generally regarded as corrupt.[34] The meaning of זַרְזִיר (zarzir) is uncertain,[35] however the Septuagint, which either knew a text different from the MT or was guided by a tradition that made sense of these verses, identifies zarzir as a rooster: ἀλέκτωρ ἐμπεριπατῶν θηλείαις εὔψυχος (“a cock strutting courageously among the hens”; NETS). The zarzir is likewise equated with a rooster in the Targum to Proverbs and in the Peshitta, both of which give a fuller description of the rooster’s behavior, as in the Septuagint.[36] The Latin Vulgate also identifies the zarzir as a rooster. Ginzberg notes that the Midrash Proverbs also identifies the zarzir as a rooster and comments that in Arabic zarzar means “cock.”[37] Thus, although we cannot be certain, given the strong interpretive tradition and the presence of chickens in the land of Israel in the period of the monarchy, it is quite possible that chickens are indeed mentioned at least once in the Hebrew Scriptures.

The Role of Chickens in Greco-Roman Culture

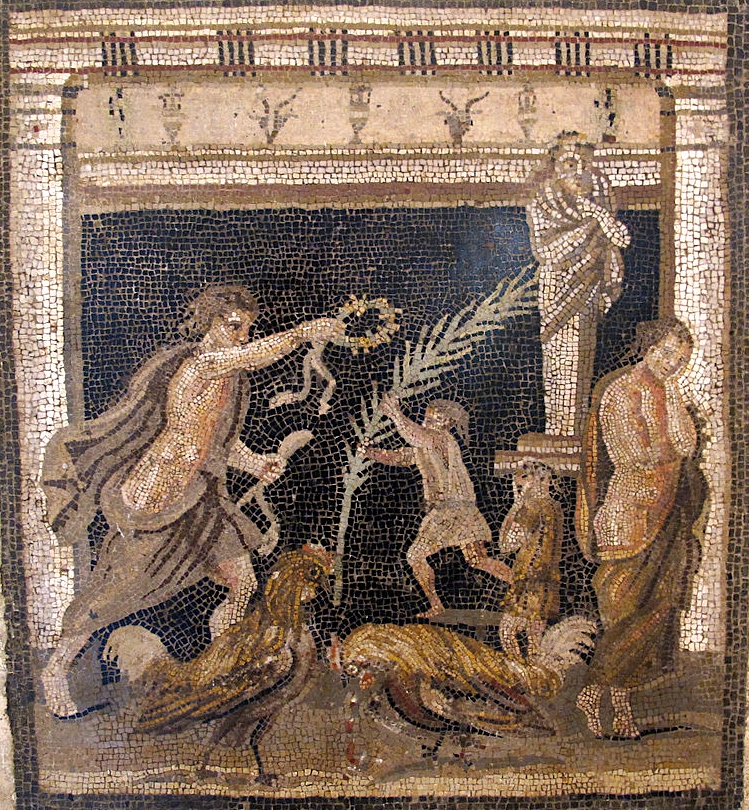

First-century mosaic from Pompeii depicting the end of a cock fight. The rooster on the left is victorious, that on the right is dripping blood and hanging its head in defeat. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Chickens had become a part of everyday life among Greeks and Romans by the first century. Chickens are mentioned in folk traditions and in learned treatises, and appeared on coins, in mosaics, on pottery, and on frescoes in Roman villas.

Cock-fighting attained an important place in Greco-Roman culture; it is mentioned in Greek literature as a favorite sport, even from an early period. Pindar (ca. 466 B.C.E.) compared an Olympic athlete to a fighting rooster in his twelfth Olympian ode. Ion the tragedian (fifth cent. B.C.E.) described a cock-fight in these words:

Battered his body and blind each eye

He rallies his courage, and faint, still crows,

For death he prefers to slavery.(Quoted by Philo of Alexandria, Prob. 134; Loeb)

The tenacity of roosters engaged in a fight was particularly admired by Greek authors.[38] Philo of Alexandria relates a legendary account of how Miltiades, an Athenian general, took his soldiers to a cock-fight. The roosters were unevenly matched and the loser, “though outdone in strength yet not outdone in courage,” continued to fight until it was dead.[39] This demonstration of bravery emboldened the troops to resist the Persian invasion of Europe.

![Roman mosaic depicting a cockfight. Two roosters meet in combat before a table displaying the winner's prizes (from right to left: a caduceus [symbol of Mercury, patron of gamblers]; a moneybag; and a palm of victory).](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/cockfight.jpg)

Roman mosaic depicting a cock-fight. Two roosters meet in combat in front of a table displaying the winner’s prizes (from left to right: a caduceus [symbol of Mercury, patron of gamblers], a moneybag, and a palm of victory). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Pliny the Elder (23–79 C.E.), who refers to annual cock-fights that were held in Pergamum, describes the attitude of the victorious rooster: “If they win the palm, they at once sing a song of victory and proclaim themselves the champions” (Nat. Hist. 10:25; Loeb). A cock-fight is even mentioned in a collection of Aesop’s fables written in the second half of the first century C.E.:

A fight took place between two cocks of the Tanagraean breed,[40] whose spirit, they say, is like that of men. The one that was worsted, being covered with wounds, ducked into a corner of the house overcome by shame; the other without delay leaped upon the housetop and flapping his wings crowed loudly. But an eagle lifted him off the roof and flew away with him. Then the other cock proceeded to tread the hens with impunity, having got a better reward for his defeat than his rival for the victory.[41] (Babrius, Aesopic Fables of Babrius in Iambic Verse, fable 5 “The Fighting Cocks”; Loeb)

Roosters also played an important role as time-keepers.[42] Pliny the Elder described roosters as “skilled astronomers,” who “recall us to our business and our labour and do not allow the sunrise to creep upon us unawares, but herald the coming day with song, while they herald that song itself with a flapping of their wings against their sides” (Nat. Hist. 10:24; Loeb). Waking workers before dawn was an important function of roosters in the age prior to the invention of the alarm clock.[43]

Roman floor mosaic ca. first cent. B.C.E.-first cent. C.E. depicting culinary delights including chickens. Photographed by Jean-Pol Grandmont, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Keeping chickens for their eggs and meat, however, was their most important function.[44] In the first century B.C.E. Marcus Terentius Varro wrote Rerum Rusticarum, an important treatise in Latin on agriculture, which included a thorough discussion of chicken farming. This treatise was followed by Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella’s treatise De Re Rustica, written in the first century C.E. Both Varro (Rerum Rusticarum 3.9.2) and Columella (De Re Rustica 8.2.1-2) observe that raising chickens was quite common.

Varro gave advice about the best breeds to select for egg and meat production (Rerum Rusticarum 3.9.4-6), the design of chicken coops (Rerum Rusticarum 3.9.6-7), the care of eggs during their incubation (Rerum Rusticarum 3.9.8-12), and of the chicks after they have hatched (Rerum Rusticarum 3.9.13-16). Varro stressed the importance of light, air, and cleanliness for raising healthy chickens, and mentioned their need to be allowed to go outdoors: “The chickens must be brought out into the sunlight and to the dung-hill[45] where they may tumble about, for so they grow better” (Rerum Rusticarum 3.9.14; Loeb). Columella repeated much of Varro’s advice, but also discussed chicken feed (Columella preferred half-cooked barley, “for it both increases the size of the eggs and makes them lay more often” [De Re Rustica 8.5.2; cf. 8.4; Loeb]), egg preservation (De Re Rustica 8.6), and the fattening of hens (De Re Rustica 8.7).

Chickens in Ancient Jewish Culture

By the first century C.E., chickens had become as fully integrated into Jewish culture as they had in the broader Greco-Roman civilization. Chickens are mentioned in the New Testament as part of Jewish daily life, Philo of Alexandria refers to chickens at least once in his writings, and chickens are mentioned frequently in the earliest layers of rabbinic literature.

According to the Mishnah, raising chickens and selling chickens and eggs was common throughout the land of Israel (m. Bab. Kam. 10:9; cf. m. Avod. Zar. 1:5). There are numerous references to chickens being raised in the courtyards shared by adjoining homes (cf. m. Ned. 5:1; m. Bab. Bat. 3:5; t. Bab. Bat. 2:13). That chickens were valued for their egg laying is shown by the ruling that if a person consecrated a hen, then the law of sacrilege applies both to the hen and its eggs (m. Meil. 3:5). The tractate Betzah (“egg”) begins with a discussion of the status of an egg that is laid on a Jewish holy day. From clarifying statements in the Tosefta and the Talmud it is clear that a chicken’s egg is what the rabbis primarily had in mind.[46]

According to the Mishnah, raising chickens and selling chickens and eggs was common throughout the land of Israel (m. Bab. Kam. 10:9; cf. m. Avod. Zar. 1:5). There are numerous references to chickens being raised in the courtyards shared by adjoining homes (cf. m. Ned. 5:1; m. Bab. Bat. 3:5; t. Bab. Bat. 2:13). That chickens were valued for their egg laying is shown by the ruling that if a person consecrated a hen, then the law of sacrilege applies both to the hen and its eggs (m. Meil. 3:5). The tractate Betzah (“egg”) begins with a discussion of the status of an egg that is laid on a Jewish holy day. From clarifying statements in the Tosefta and the Talmud it is clear that a chicken’s egg is what the rabbis primarily had in mind.[46]

Most of the practices associated with chicken raising described by Varro and Columella are also found in rabbinic literature. So, for example, we hear of the construction of chicken coops (e.g., t. Shab. 14:1) and of boxes in which hens can nest (m. Pes. 4:7). There are also discussions about lending one’s hen to a fellow to hatch chicks (m. Bab. Metz. 5:4), and about fattening chickens for meat (m. Shab. 24:3; b. Bab. Metz. 86b).

From a number of references, it appears that raising chickens was often a task assigned to Jewish women. The rabbis discuss scenarios in which a woman rents a hen to her friend to incubate eggs in return for two chicks a year (t. Bab. Metz. 4:24), or in which a woman says to her friend, “The hen is mine, the eggs are yours, and we’ll divide up the chicks” (t. Bab. Metz. 4:25). The rabbis also state that “She who takes hens from her friend for raising chicks takes care of the chicks for as long as they need their mother” (t. Bab. Metz. 5:5). These rulings, which are formulated with reference to women, probably reflect a cultural norm according to which raising chickens was mainly a woman’s duty.[47]

Rabbinic literature also attests to the fact that chickens can often be a nuisance. For instance, the rabbis ruled that a chicken’s owner is liable to pay damages for anything a chicken might break as it walks along (m. Bab. Kam. 2:1). If someone’s chickens were to peck or scratch at another person’s dough or fruit, the rabbis ruled that the owner of the chickens had to pay half damages to the owner of the damaged goods. But if the chickens scratched dirt into the fruit or dough, then the owner of the chickens was required to pay full damages for the ruined goods (t. Bab. Kam. 2:1). Likewise, if someone’s chickens pecked at the rope of a well-bucket causing it to fall and break, the owner of the chickens was required to pay full damages. And if a chicken went into a vegetable garden and broke the seedlings and stripped the leaves off the plants, the chicken’s owner payed full damages (ibid.). The rabbis also discuss what to do when a chicken suspected of drinking impure liquid is found pecking at dough (m. Toh. 3:8). In another discussion, the rabbis consider the ritual status of an oven should a rooster that had swallowed an impure creeping animal fall into the oven and die (m. Kel. 8:5). These rabbinic discussions not only show how much of a nuisance a chicken can be, but also indicate how common chicken raising had become.

Rabbinic literature also attests to the fact that chickens can often be a nuisance. For instance, the rabbis ruled that a chicken’s owner is liable to pay damages for anything a chicken might break as it walks along (m. Bab. Kam. 2:1). If someone’s chickens were to peck or scratch at another person’s dough or fruit, the rabbis ruled that the owner of the chickens had to pay half damages to the owner of the damaged goods. But if the chickens scratched dirt into the fruit or dough, then the owner of the chickens was required to pay full damages for the ruined goods (t. Bab. Kam. 2:1). Likewise, if someone’s chickens pecked at the rope of a well-bucket causing it to fall and break, the owner of the chickens was required to pay full damages. And if a chicken went into a vegetable garden and broke the seedlings and stripped the leaves off the plants, the chicken’s owner payed full damages (ibid.). The rabbis also discuss what to do when a chicken suspected of drinking impure liquid is found pecking at dough (m. Toh. 3:8). In another discussion, the rabbis consider the ritual status of an oven should a rooster that had swallowed an impure creeping animal fall into the oven and die (m. Kel. 8:5). These rabbinic discussions not only show how much of a nuisance a chicken can be, but also indicate how common chicken raising had become.

Chickens in Jerusalem

Perhaps it was on account of their ability to cause mischief that the rabbis ruled that “They may not raise chickens in Jerusalem on account of the holy things [i.e., sacrifices], and priests may not raise them in the Land of Israel because of purity,” (m. Bab. Kam. 7:7). A prohibition against raising chickens in Jerusalem is also mentioned in the Dead Sea Scrolls (11QTc [11Q21] 3 I, 1-5).

This prohibition is not easily reconciled with numerous reports that chickens were, in fact, raised in Jerusalem. For instance, there is the testimony in the Mishnah that a rooster was stoned in Jerusalem because it had killed a human being (m. Edu. 6:1).[48] There are also numerous references to the timing of activities in the Temple at or near cockcrow (e.g., m. Yom. 1: 8; m. Suk. 5:4). That Temple activities depended on hearing a rooster crow strongly suggests that chickens were, in fact, raised in Jerusalem because the rooster would have to be within earshot.

It therefore appears that the prohibition stated in 11QTc 3 I, 1-5 and m. Bab. Kam. 7:7 represents a stringent opinion that does not reflect the common practice in Jerusalem during the days of the Second Temple. Indeed, in the Tosefta we find a different version of the ruling, which states: “They may not raise chickens on account of the holy things, but if one provides them a garden or a dung heap, it is permitted” (t. Bab. Kam. 8:10).[49] Excavations in the City of David and the Ophel areas of Jerusalem confirm the presence of chickens—at least slaughtered ones bought in the markets—in the Holy City during the early Roman period.[50]

Cockcrow: Between Night and the Break of Day

We have just alluded to the fact that certain activities in the Temple were timed in keeping with cockcrow. One of these activities was the daily removal of ashes from the altar:

בְּכָל יוֹם תּוֹרְמִים אֶת הַמִּזְבֵּחַ מִקְּרוֹת הַגֶּבֶר אוֹ {ש}סָמוּךְ לוֹ, בֵּין מִלְּפָנָיו וּבֵין מִלְּאַחֲרָיו. וּבְיוֹם הַכִּפּוּרִים מֵחֲצוֹת, וּבָרְגָלִים מֵאַשְׁמוֹרָת הָרִאשׁוֹנָה, וְלֹא הָיְתָה {מ}קְרוֹת הַגֶּבֶר מַגַּעַת עַד שֶׁהָיְתָה עֲזָרָה מְלֵיאָה מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל:

Every day they remove the ashes from the altar מִקְּרוֹת הַגֶּבֶר [miqerot hagever, “at cockcrow”][51] or close to it, either before or after. But on the Day of Atonement [they remove the ashes] at midnight, and on pilgrimage festivals at the first watch [of the night], and cockcrow had not arrived before the courtyard was full of Israelites. (m. Yom. 1:8 [Kaufmann]; cf. y. Yom. 7b-8a halakhah 7)

According to m. Tam. 1:2, cockcrow was also the time when the superintendent (מְמֻנֶּה, memuneh) arrived at the Temple each morning.

Cockcrow was an important time marker for the fulfillment of certain mitzvot outside the Temple as well. For example, it was Rabban Gamliel’s opinion that the evening Shema could be recited until cockcrow (Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version A, chap. 2 [ed. Schechter, p. 14]). Likewise, cockcrow marked the starting point of fast-days (t. Taan. 1:6[5]; cf. y. Taan. 5b halakhah 4; b. Taan. 12a; b. Pes. 2b). Cockcrow also plays a role in certain stories about Passover. According to one story,

It once happened that Rabban Gamliel and the elders who were gathered in the house of Boethus ben Zonin in Lod were occupied with the halakhot of Passover all night until cockcrow. (t. Pes. 10:12[8])

Cockcrow also plays a role in a dispute between the schools of Hillel and Shammai over the recitation of Hallel (Psalms 113-118) on the first night of Passover. It was customary on the first night of Passover to recite part of Hallel before the meal, and the rest of Hallel after the meal.[52] At the conclusion of the first part of Hallel before the commencement of the meal, a blessing for redemption was recited. The point of dispute between the schools of Hillel and Shammai was where the first part of Hallel should end. Should the recitation before the meal end at the conclusion of Psalm 114 (the opinion of the school of Hillel), or should the recitation before the meal end at the conclusion of Psalm 113 (the opinion of the school of Shammai)? The opinion of the school of Shammai was based on the content of Psalm 114, which describes the departure from Egypt and the parting of the Red Sea:

To what point does he say [Hallel]? Beit Shammai says, “Until, ‘a happy mother of children’ (Ps. 113:9).” And Beit Hillel says, “Until, ‘a flint into a spring of water’ (Ps. 114:8), and he concludes with the blessing for redemption.” Beit Shammai said to Beit Hillel, “Have they already gone forth that they should mention the exodus from Egypt?” Beit Hillel said to them, “Even if he waits until קרית הגבר [‘cockcrow’], it is clear that they had not gone forth until the sixth hour of the day. How then can he say the blessing for redemption if they had not yet been redeemed?” (t. Pes. 10:9[6]; cf. y. Pes. 70b halakhah 5)

The school of Shammai regarded the Passover meal as a reenactment of the Exodus, and therefore they wanted to put off the recitation of Psalm 114 until after the meal because mentioning the departure from Egypt and the parting of the Red Sea meant getting ahead of the chronology. The school of Hillel rejected the opinion of the school of Shammai because both schools agreed that the blessing for redemption was recited before the Passover meal. If it was permissible to recite a blessing for the redemption before the meal, which meant getting ahead of the Exodus chronology, why be a stickler about the content of Psalm 114?

In the dispute over the recitation of Hallel, cockcrow serves as an important time marker, because the Passover lamb had to be eaten before daybreak (Exod. 12:10). It is clear, therefore, that cockcrow marks the division between night and day—it is a liminal moment with halakhic significance for the performance of certain time-bound mitzvot (cf. b. Zev. 20a-b). Perhaps it is on account of its halakhic significance that there is a special blessing that is recited at cockcrow:

כי שמע קול תרנגולא, לימא: ברוך אשר נתן לשכוי בינה להבחין בין יום ובין לילה.

When he hears the rooster’s crow [קול תרנגולא] he should say: “Blessed is he who gave the rooster [שכוי] understanding to distinguish between day and night.” (b. Ber. 60b)

Cockcrow as a time marker of the division between night and day is also attested in the New Testament:

Watch therefore—for you do not know when the master of the house will come, in the evening, or at midnight, or at ἀλεκτοροφωνίας [alektorofōnias, “cockcrow”], or in the morning. (Mark 13:35)

Chickens in Jewish Folklore

Detail of Ma’on synagogue mosaic depicting a hen laying an egg (sixth cent. C.E.). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Chickens eventually earned a place in Jewish folklore, much as they had done, for example, in Aesop’s Fables. Chickens even appear in parables that illustrate stories in the Bible. For instance, in order to describe God’s frustration toward Israel’s complacency when the Philistines had captured the ark of the covenant (cf. 1 Sam. 6:1), Rabbi Jeremiah told a parable in the name of Rabbi Samuel son of Rav Isaac:

The Holy One, blessed be he, said: “If even one of their chickens was lost, would not its owner have gone in search of it through many houses in order to bring it back? Yet my ark has been in the country of the Philistines for seven months and you don’t care about it. If you don’t care, then I myself will care for it.” (Gen. Rab. 54:4)

Likewise, Resh Laqish told a parable about king Saul’s consultation with a medium:

To what may Saul in that hour be compared? Resh Laqish said, “He was like a king who entered a province and decreed, ‘All the chickens that are here must be slaughtered.’ Then one night he wanted to go out, so he said, ‘Is there a rooster here that will crow?’ So they said to him, ‘Wasn’t it you who made a decree and said, “Every chicken that is here must be slaughtered?”’ Even so, Saul banished the ghosts and the mediums from the land and then he said, ‘Seek a woman who consults ghosts for me…. [1 Sam. 28:7].’” (Lev. Rab. 26:7)

Chickens in the New Testament

We have seen that by the first century C.E. chickens had been fully adopted into Greco-Roman and Jewish culture. It is not surprising, therefore, that chickens play a role in the life and the teachings of Jesus.

In addition to the passage from Mark cited above (Mark 13:35), chickens may be referred to in two other sayings of Jesus. In his teaching about the character of the heavenly Father, Jesus said:

Which of you fathers, if your son asks for a fish, will, instead of a fish, give him a snake? Or if your son asks for an egg, will give him a scorpion? (Luke 11:11-12)

Since most eggs consumed by first-century Jews in the land of Israel came from chickens,[53] it is probable that a chicken’s egg was what Jesus had in mind and what his audience would have envisioned.

Chickens may also have been envisioned in Jesus’ lament over Jerusalem (Matt. 23:37; Luke 13:34):[54]

Jerusalem, Jerusalem, who kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her! How often I wanted to gather your children as a bird gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were unwilling.

A chicken as depicted in the mosaic floor of the Byzantine church discovered at Kursi, the traditional site of the miracle of the exorcism of Legion and the drowning of the swine. Photographed by the author.

The word for “bird” (ὄρνις) in this passage is generic and can be used to refer to any bird.[55] The action of a dam gathering chicks under her wings could also describe any bird, so it is not certain that Jesus intended to refer specifically to a hen gathering her chicks. It is even possible that Jesus intended to allude to the commandment to drive away a mother bird from her nest before collecting the young (Deut. 22:6-7; cf. the similar vocabulary in LXX). On the other hand, the image of a hen guarding her chicks was an everyday sight, and it is possible that chickens would have been the first birds that would have come to the minds of Jesus’ audience.

Peter’s Denial

The most famous chicken in the New Testament is, of course, the rooster that crowed in the story of Peter’s denial of Jesus. Jesus’ prediction of Peter’s denial and the description of the denial are reported in all four canonical Gospels. And in each of the Gospels it is the rooster’s crow that is the turning point of the story.

The way Jesus’ prediction and the description of the denial are reported in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke poses an interesting synoptic problem. According to Mark, Jesus said to Peter, “Amen! I say to you: today, this night before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me thrice,” (Mark 14:30). The problem is that the Gospel of Mark stands alone among all four canonical Gospels in reporting that the rooster crowed twice. According to the theory of Markan Priority, Luke and Matthew independently used Mark as the source for this Triple Tradition pericope. The hypothesis of Markan Priority, however, has difficulty explaining the Lukan-Matthean agreements (the so-called “minor agreements”) against Mark. How did two authors working independently from the text of Mark manage to agree on significant details and even on the wording of some of those details? Robert Lindsey proposed a solution to the Synoptic Problem that may resolve this difficulty.[56] According to Lindsey’s hypothesis Luke was written prior to Mark and Matthew. Mark wrote a paraphrased abridgment of Luke, and Matthew depended on Mark and supplemented Mark’s material with material from a source that had also been used by Luke. Lindsey’s hypothesis explains why Mark and Matthew are so similar in wording in Triple Tradition contexts, but why Luke is so different, and how Luke and Matthew often achieve such high verbal identity in Double Tradition pericopae. Lindsey’s hypothesis also offers an explanation for the Lukan-Matthean agreements against Mark in Triple Tradition contexts: these agreements are the result of Matthew’s use of one of Luke’s pre-synoptic sources.

In their versions of Jesus’ prediction and in their descriptions of Peter’s denial, the most significant Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark is their report of only one instance of the rooster crowing, whereas in Mark’s version the rooster crows twice. A comparison of the three synoptic accounts shows that Luke’s version preserves several details that seem closer to a Jewish context, which may in turn indicate that Luke’s version is more authentic. Some of Luke’s authentic-sounding details are confirmed by the Gospel of Matthew.[57]

Whether or not Lindsey’s synoptic hypothesis is accepted, what we have learned about chickens in first-century Jewish culture lends Luke’s version of Jesus’ prediction and Luke’s description of Peter’s denial an air of authenticity. In Luke’s version Jesus tells Peter, “The rooster will not crow today until you deny three times that you know me.” Not only does the structure of Jesus’ prediction resemble a rabbinic statement (m. Yom. 1:8), but the moment of cockcrow plays the role of an important time marker in Luke’s version of Jesus’ prediction (and likewise in the Matthean and Johannine versions), just as we have seen in rabbinic sources.

Conclusion

Our examination of chickens in first-century Jewish society has given us a tiny glimpse into the cultural context of the Gospels. Appreciation for the cultural significance of chickens in late Second Temple Jewish culture may be a relatively obscure subject, but it has helped us to evaluate the authenticity of the differing versions of the story of Peter’s denial in the Gospels.

A rooster pecks at a cluster of grapes in this fresco from Herculaneum. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

| [*] Music in the Audio JP files is excerpted from the Hebrew song Moshe written by Immanuel Zamir in a recording sung by Yaffa Yarkoni obtained from Wikimedia Commons. |

- [1] The author wishes to thank his friend, Hiromu Boschee Nagahara, for his help locating many of the items in the bibliography, and his wife, Lauren Asperschlager, for proofreading this article. ↩

- [2] This is stated explicitly in the Mishnah:

The commandment to cover the blood [Lev. 17:13] is more stringent than the commandment to send from the nest [Deut. 22:6-7], for covering the blood is performed for wild animals and birds, both domesticated birds and not domesticated, but sending from the nest is not performed [for any animals] except for birds, and is performed for birds only if they are not domesticated. (m. Hul. 12:1)

This mishnah goes on to specifically mention chickens, stating that the commandment to send the mother bird from the nest applies to them only if the hen is nesting in a park or an orchard, in other words, if the hen is unowned. ↩

- [3] John P. Peters (“The Cock,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 33 [1913]: 363-396) drew the same inference with respect to the biblical laws of sacrifice. ↩

- [4] See, for example, Henry Baker Tristram, The Natural History of the Bible (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1883), 221; Peters, “The Cock,” 370; W. Stewart McCullough, “Fowl,” The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (ed. George Arthur Buttrick, et al.; 4 vols.; Nashville: Abingdon, 1962), 2:323; Merling K. Alomia, “Tell Hesban 1976: Notes on the Present Avifauna of Tell Hesban,” Andrews University Seminary Studies 16 (1978): 289-303, esp. 302. ↩

- [5] R. D. Crawford, “Origin and History of Poultry Species,” in Poultry Breeding and Genetics (ed. R. D. Crawford; Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1990), 5-6. ↩

- [6] Barbara West and Ben-Xiong Zhou, “Did Chickens Go North? New Evidence for Domestication,” Journal of Archaeological Science 15 (1988): 515-533. ↩

- [7] Alice A. Storey, J. Stephen Athens, David Bryant, Mike Carson, Kitty Emery, et al., “Investigating the Global Dispersal of Chickens in Prehistory Using Ancient Mitochondrial DNA Signatures” PLoS ONE 7.7; e39171; (2012): 2. ↩

- [8] On the skeletal remains of chickens found at Mohejo-daro, see John Marshall, Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization (3 vols.; London: Probsthain, 1931), 2:662. ↩

- [9] Frederick Zeuner, A History of Domesticated Animals (New York: Harper & Row, 1963), 443-444. ↩

- [10] Crawford, “Origin and History of Poultry Species,” 9. ↩

- [11] Zeuner, History of Domesticated Animals, 445. W. Stewart McCullough (“Fowl,” 323) mentions two neo-Babylonian cylinder seals (626-539 B.C.E.) with images of roosters, but does not mention where they were discovered or where they were published. ↩

- [12] J. B. Coltherd, “The Domestic Fowl in Ancient Egypt,” Ibis 108 (1966): 217-223, esp. 217; Walter E. Aufrecht (“A Phoenician Seal,” in Solving Riddles and Untying Knots: Biblical, Epigraphic, and Semitic Studies in Honor of Jonas C. Greenfield [ed. Ziony Zevit, Seymour Gitin, and Michael Sokoloff; Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1995], 385-387) discusses a Phoenician seal of unknown provenance dated to the eighth century B.C.E. which shows two roosters facing one another (cf. Nahman Avigad, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals [ed. Benjamin Sass; Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1997], 433 [no. 1142]). Zeuner (History of Domesticated Animals, 446) mentions roosters that are depicted on Proto-Corinthian pottery from the second half of the eighth century B.C.E. ↩

- [13] Zeuner, History of Domesticated Animals, 446-449. Peters (“The Cock,” 382) claims that “Throughout the whole Greek world…from 700 B.C. onward, the cock…was a familiar and omnipresent bird.” ↩

- [14] The earliest references to chickens in Greek literature are made by Theognis of Megara (latter half of the sixth century B.C.E.) and Heraclitus the Ephesian (ca. 535-475 B.C.E.) who remarked on the fact that chickens bathe themselves with dust or ashes (cited by Columella [first cent. C.E.], On Agriculture, 8.4.4). Chickens are mentioned in the works of Plato (ca. 427-347 B.C.E), and Aristotle (ca. 384-322 B.C.E.) was fully acquainted with chickens. In his History of Animals, Aristotle describes chicken anatomy (2.8.6 [comb]; 2.12.14 [crop]), mating habits (5.2.2; 5.11.1; 9.26.5), the rooster’s crow (4.9.7), and their habit of cleaning themselves in the dust (9.26.5). Aristophanes (ca. 414 B.C.E.), in his play The Birds (lines 707, 833), referred to chickens as ὄρνις…τοῦ γένους τοῦ Περσικοῦ (ornis tou genous Persikou, “a bird…of the Persian breed”), which is sometimes interpreted as an indication of the region from which chickens were introduced to the Greeks. Aristophanes also mentions chickens in The Clouds (lines 661-666, 848-852, 1430); in The Frogs (line 1342); and in The Wasps (lines 100, 794, 1490). ↩

- [15] Storey, Athens, Bryant, Carson, Emery, et al., “Investigating the Global Dispersal of Chickens in Prehistory,” 7. ↩

- [16] Coltherd, “The Domestic Fowl in Egypt,” 219. Coltherd mentions that the stone blocks were reused in another temple from the eighteenth dynasty and that the graffiti must have been drawn when the stones were in their original position prior to this secondary usage. ↩

- [17] See Percy R. Lowe, “A Further Note Bearing on the Date When the Domestic Fowl Was First Known to the Ancient Egyptians,” Ibis 13.4 (1934): 378-382. ↩

- [18] Coltherd, “The Domestic Fowl in Egypt,” 219; James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (3d ed.; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 240 n. 19. ↩

- [19] Howard Carter, “An Ostracon Depicting a Red Jungle-Fowl (The Earliest Known Drawing of the Domestic Cock),” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 9 (1923): 1-4; Percy R. Lowe, “A Note on the Earliest Appearance of the Cock in Egypt,” Ibis 12.5 (1929): 5:20-41. ↩

- [20] Zeuner, History of Domesticated Animals, 444-445; Coltherd, “The Domestic Fowl in Egypt,” 221-222; Crawford, “Origin and History of Poultry Species,” 13. ↩

- [21] Mikhael Taran, “Early Records of the Domestic Fowl in Ancient Judea,” Ibis 117.1 (1975): 109-110. ↩

- [22] See James B. Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near East in Pictures (2d ed.; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 345 (image), 375 (description); no. 793. ↩

- [23] Nahman Avigad, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals, 52 (no. 8), 54 (no. 13). ↩

- [24] Avigad, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals, 54. ↩

- [25] See also Pritchard, Ancient Near East in Pictures, 85 (image), 280 (description); no. 277. ↩

- [26] Cf. Jer. 40:8 where his name is spelled יְזַנְיָהוּ (yezanyāhu). ↩

- [27] Avigad, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals, 52. ↩

- [28] Joachim Boessneck and Angela von den Driesch, “Tell Hesban 1976: Preliminary Analysis of the Animal Bones from Tell Hesban,” Andrews University Seminary Studies 16 (1978): 259-288. Two chicken bones at Tell Hesban were found in strata from earlier periods (ca. 1200-900 B.C.E.). Nevertheless Boessneck and von den Driesch warn that such isolated finds must be treated with caution: “The presence of these bones may be due to either disturbances in the archaeological strata or to human error in processing the bones following excavation” (ibid., 266). The same caution must be taken with the three chicken bones dated to the tenth century B.C.E. at Lachish mentioned by West and Zhou, “Did Chickens Go North?” 520. As Boessneck and von den Driesch warned, “Such isolated finds are best not considered in a careful interpretation” (“Tell Hesban 1976: Preliminary Analysis of the Animal Bones from Tell Hesban,” 266). ↩

- [29] See Liora Kolska Horwitz and Eitan Tchernov, “Bird Remains from Areas A, D, H and K,” in Excavations at the City of David 1978-1985 Directed by Yigal Shiloh Vol. IV Various Reports (ed. Donald T. Ariel and Alon de Groot) Qedem 35 (1996): 298-301. ↩

- [30] The statement that “the species of clean birds are innumerable” appears in the same context. Cf. m. Hul. 3:6. ↩

- [31] According to Ginzberg, this is the Babylonian name for chickens which the Jews brought back with them to the land of Israel when they returned from exile. Louis Ginzberg, “Cock,” Jewish Encyclopedia (12 vols.; ed. Isidore Singer; New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1901-1906), 4:138-139. ↩

- [32] The earliest attestation of the noun תַּרְנְגוֹל (tarnegōl, “rooster”) was discovered in a Dead Sea Scrolls fragment (11QTc [11Q21] 3 I, 1-5). On this document, see Elisha Qimron, “The Chicken and the Dog in the Temple Scroll—11QTc (Col. XLVIII),” Tarbiz 54 (1995): 473-476. (Click here for an English translation of Qimron’s article.) ↩

- [33] Ancient interpreters of Scripture have supposed that references to chickens may be found in 1 Kings 4:23, Isaiah 22:17 and Job 38:36.

1 Kings 4:23 describes the daily provisions for king Solomon’s table: ten fat oxen, and twenty pasture-fed cattle, one hundred sheep, besides deer, gazelles, roebucks, וּבַרְבֻּרִים אֲבוּסִים (ūvarburim ‘avūsim, “and fatted fowl”; RSV). The Hebrew word is uncertain, this being its sole occurrence in Scripture. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon offers a variety of options for translating בַּרְבֻּרִים including capons (castrated roosters), geese, swans, guinea-hens, and simply “fowls” (Francis Brown, S.R. Driver, and Charles A. Briggs, The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon [Boston, Mass.: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1906; repr., Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2000], 141). In modern Hebrew בַּרְבּוּר means “swan.”

A talmudic discussion offers a variety of interpretations:

What is meant by ‘fatted fowl’?—Rab said: [Fowls] fed against their will. Samuel said: [Fowls] naturally fat. R. Johanan said: Oxen which had never toiled were brought from the pastures, and likewise chickens (תרנגולת) [that had never toiled] from their dung heaps…. Amemar said: A fattened black hen which moves about the vats, and which cannot step over a stick. (b. Bab. Metz. 86b; Soncino)

The Septuagint rendered בַּרְבֻּרִים אֲבוּסִים as ὀρνίθων ἐκλεκτῶν (ornithōn eklektōn, “choice birds”), a cautious translation that does not help with identification since ὄρνις (ornis) is the generic word for “bird” in Greek. According to Liddell and Scott, in Attic Greek ὁ ὄρνις does mostly refer to the rooster and ἡ ὄρνις to the hen, “being the commonest and most useful of domestic fowls” (Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon [7th ed.; New York: Harper, 1883], 1077), but it seems that the translators of the Septuagint were intentionally vague. F. S. Bodenheimer (Animal and Man in Bible Lands [Leiden: Brill, 1960], 190) suggested that בַּרְבֻּרִים אֲבוּסִים refers to fattened geese, while G. R. Driver (“Birds in the Old Testament: II. Birds in Life,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 87.2 [1955], 129-140, esp.133-134) was inclined to identify them as chickens. Nevertheless, the identification of the fowl in 1 Kings 4:23 must remain inconclusive.

Isaiah 22:17 reads: הִנֵּה יי מְטַלְטֶלְךָ טַלְטֵלָה גָּבֶר וְעֹטְךָ עָטֹה “Beware, the LORD is about to take firm hold of you and hurl you away, you גֶּבֶר [gever, ‘mighty man’]” (NIV). According to certain ancient traditions, גֶּבֶר was understood to refer to a rooster. Ginzberg cites Lev. Rab. 5:5 and Midrash Proverbs 30:19 (Ginzberg, “Cock,” 4:138-139). Peters (“The Cock,” 366) noted that Jerome, in his Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible, accepted this rabbinic tradition of interpretation, and that Eusebius of Caesarea also mentions this rabbinic interpretation in his commentary on Isaiah. In mishnaic Hebrew “rooster” is a secondary meaning of gever, but there is no evidence that gever had this meaning in biblical Hebrew. It therefore seems probable that the later meaning of gever sparked the midrashic interpretations of Isaiah 22:17.

Job 38:36 reads: מִי־שָׁת בַּטֻּחֹות חָכְמָה אֹו מִי־נָתַן לַשֶּׂכְוִי בִינָה “Who has put wisdom in the clouds, or given understanding to the שֶׂכְוִי [sekhvi, ‘mists’]?” (RSV). Since sekhvi appears only here in the Hebrew Bible, it is difficult to ascertain its meaning. The context dictates a meaning related to clouds, hence “mists” in the RSV. Nevertheless, rabbinic traditions often associate sekhvi with roosters, as in the blessings recited at dawn, which clearly echo Job 38:36: “When he hears the cock crowing [קול תרנגולא] he should say: ‘Blessed is He who has given to the cock [שכוי] understanding to distinguish between day and night’” (b. Ber. 60b). ↩

- [34] See Peters, “The Cock,” 368-369; R. B. Y. Scott, Proverbs · Ecclesiastes (AB 18; Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1965), 182. ↩

- [35] Some translations, e.g., KJV, render zarzir as “greyhound.” ↩

- [36] Peters, “The Cock,” 368. ↩

- [37] Ginzberg, “Cock,” 139. ↩

- [38] Columella writes somewhat scornfully of the Greeks’ enthusiasm for cock-fighting:

…we [Romans] lack the zeal displayed by the Greeks who prepared the fiercest birds they could find for contests and fighting. Our aim is to establish a source of income for an industrious master of a house, not for a trainer of quarrelsome birds, whose whole patrimony, pledged in a gamble, generally is snatched from him by a victorious fighting-cock. (Columella, De Re Rustica 8.2.5; Loeb)

- [39] Philo, Prob. §131-133. ↩

- [40] Varro (Rerum Rusticarum 3.9.6) singles out this breed as fit for cock-fighting, but not for raising flocks for egg and meat production. Columella likewise notes that, “The Greeks…since they desired height of body and determined courage in the fray, esteemed most highly the Tanagran [breed]….” (De Re Rustica 8.2.4). ↩

- [41] The description of the surviving rooster is similar to the LXX version of Proverbs 30:31. ↩

- [42] As early as the fifth century B.C.E. Aristophanes referred to cockcrow as the time for servants to rise (Aristophanes, Clouds, lines 4-5). ↩

- [43] As Zeuner (History of Domesticated Animals, 449) observed. ↩

- [44] See Don Brothwell and Patricia Brothwell, Food in Antiquity: A Survey of the Diet of Early Peoples (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1969), 54-55. ↩

- [45] The sight of chickens scratching at a dunghill must have been a common one. The story of a rooster who finds a pearl in a dungheap is included in Phaedrus’ first-century C.E. collection of Aesop’s Fables (Book III fable 12). Chickens are also frequently associated with dungheaps in rabbinic literature (cf. t. Bab. Kam. 8:10; b. Bab. Metz. 86b). ↩

- [46] Cf. t. Betz. 1:2, “…he who slaughters a hen and finds eggs in it….” and b. Betz. 2a,“What are we discussing? If one should say about a hen kept for food…and [if] about a hen kept for laying eggs….” Broshi states that “Jews consumed chicken eggs mostly, but they also ate the eggs of any ‘clean’ fowl” (Magen Broshi, “The Diet of Palestine in the Roman Period—Introductory Notes,” Israel Museum Journal 5 [1986]: 41-56, quote on p. 51). ↩

- [47] See Ze’ev Safrai, “Agriculture and Farming,” in The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Daily Life in Roman Palestine (ed. Catherine Hezer; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 246-263, esp. 260. ↩

- [48] See Qimron, “The Chicken and the Dog in the Temple Scroll,” 474 n. 8 (Click here for an English translation of Qimron’s article.); Jodi Magness, “Dogs and Chickens at Qumran,” The Dead Sea Scrolls and Contemporary Culture (ed. Adolfo D. Roitman, Lawrence H. Schiffman and Shani Tzoref; Leiden: Brill, 2011, 349-362. ↩

- [49] But see Avot de-Rabbi Natan, Version A, chap. 35: “Neither geese nor chickens may be raised there [i.e., Jerusalem], nor, needless to say, pigs. No dunghills may be kept there on account of purity.” ↩

- [50] See Horowitz and Tchernov, “Bird Remains from Areas A, D, H and K,” 300. ↩

- [51] The idiom קְרוֹת הַגֶּבֶר (variants: קְרֹאוֹת הַגֶּבֶר, e.g., m. Tam. 1:2; or קְרִיאַת הַגֶּבֶר, e.g., y. Taan. 5b halakhah 4; b. Yom. 20a; and קְרִייַת הַגֶּבֶר, e.g., b. Zev. 86b), lit. “calling of the man,” consistently appears in rabbinic literature as the time of cockcrow. Likewise, the action of a rooster crowing is קָרָא הַגֶּבֶר (m. Suk. 5:4). ↩

- [52] Shmuel Safrai and Ze’ev Safrai, Haggadah of the Sages (trans. Miriam Schlüsselberg; Jerusalem: Carta, 2009), 212. ↩

- [53] See above, n. 43. ↩

- [54] The wording of Jesus’ lamentation is nearly identical in Matthew and Luke, suggesting that it was copied from a common source. ↩

- [55] See above, n. 30. ↩

- [56] See Robert L. Lindsey, “A New Two-source Solution to the Synoptic Problem”; idem, “A New Approach to the Synoptic Gospels”; idem, “Introduction to A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark”; idem, “Measuring the Disparity Between Matthew, Mark and Luke.” ↩

- [57] Below is a comparison of the synoptic versions of Jesus’ prediction (Matt. 26:34; Mark 14:30; Luke 22:34) and the descriptions of Peter’s denial (Matt. 26:69-75; Mark 14:66-72; Luke 22:54-62):

Luke 22:34 Mark 14:30 Matthew 26:34 L1 ὁ δὲ εἶπεν καὶ λέγει αὐτῷ ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἔφη αὐτῷ ὁ Ἰησοῦς L2 Ἀμὴν Ἀμὴν L3 Λέγω σοι, λέγω σοι λέγω σοι L4 ὅτι σὺ ὅτι L5 Πέτρε, οὐ φωνήσει L6 σήμερον σήμερον L7 ταύτῃ τῇ νυκτὶ πρὶν ἐν ταύτῃ τῇ νυκτὶ πρὶν L8 ἢ δὶς L9 ἀλέκτωρ ἀλέκτορα φωνῆσαι ἀλέκτορα φωνῆσαι L10 ἕως τρίς με ἀπαρνήσῃ εἰδέναι. τρίς με ἀπαρνήσῃ. τρὶς ἀπαρνήσῃ με. Luke 22:54-62 Mark 14:66-72 Matthew 26:69-75 L11 22:54 Συλλαβόντες δὲ αὐτὸν ἤγαγον καὶ εἰσήγαγον εἰς τὴν οἰκίαν τοῦ ἀρχιερέως· ὁ δὲ Πέτρος ἠκολούθει μακρόθεν. 14:66 Καὶ ὄντος τοῦ Πέτρου 26:69 Ὁ δὲ Πέτρος L12 55 περιαψάντων δὲ πῦρ ἐν μέσῳ τῆς αὐλῆς καὶ συγκαθισάντων ἐκάθητο ὁ Πέτρος μέσος αὐτῶν. κάτω ἐν τῇ αὐλῇ ἔρχεται μία τῶν παιδισκῶν τοῦ ἀρχιερέως, ἐκάθητο ἔξω ἐν τῇ αὐλῇ· καὶ προσῆλθεν αὐτῷ μία παιδίσκη L13 56 ἰδοῦσα δὲ αὐτὸν παιδίσκη τις καθήμενον πρὸς τὸ φῶς καὶ ἀτενίσασα αὐτῷ εἶπεν· 67 καὶ ἰδοῦσα τὸν Πέτρον θερμαινόμενον ἐμβλέψασα αὐτῷ λέγει· λέγουσα· L14 Καὶ οὗτος σὺν αὐτῷ ἦν· Καὶ σὺ μετὰ τοῦ Ναζαρηνοῦ ἦσθα τοῦ Ἰησοῦ· Καὶ σὺ ἦσθα μετὰ Ἰησοῦ τοῦ Γαλιλαίου· L15 57 ὁ δὲ ἠρνήσατο λέγων· 68 ὁ δὲ ἠρνήσατο λέγων· 70 ὁ δὲ ἠρνήσατο ἔμπροσθεν πάντων λέγων· L16 Οὐκ οἶδα αὐτόν, γύναι. Οὔτε οἶδα οὔτε ἐπίσταμαι σὺ τί λέγεις, Οὐκ οἶδα τί λέγεις. L17 καὶ ἐξῆλθεν ἔξω εἰς τὸ προαύλιον 71 ἐξελθόντα δὲ εἰς τὸν πυλῶνα L18 καὶ ἀλέκτωρ ἐφώνησεν. L19 58 καὶ μετὰ βραχὺ ἕτερος ἰδὼν αὐτὸν ἔφη· 69 καὶ ἡ παιδίσκη ἰδοῦσα αὐτὸν ἤρξατο πάλιν λέγειν τοῖς παρεστῶσιν ὅτι εἶδεν αὐτὸν ἄλλη καὶ λέγει τοῖς ἐκεῖ· L20 Καὶ σὺ ἐξ αὐτῶν εἶ· Οὗτος ἐξ αὐτῶν ἐστιν. Οὗτος ἦν μετὰ Ἰησοῦ τοῦ Ναζωραίου· L21 ὁ δὲ Πέτρος ἔφη· 70 ὁ δὲ πάλιν ἠρνεῖτο. 72 καὶ πάλιν ἠρνήσατο μετὰ ὅρκου ὅτι L22 Ἄνθρωπε, οὐκ εἰμί. Οὐκ οἶδα τὸν ἄνθρωπον. L23 59 καὶ διαστάσης ὡσεὶ ὥρας μιᾶς ἄλλος τις διϊσχυρίζετο λέγων· καὶ μετὰ μικρὸν πάλιν οἱ παρεστῶτες ἔλεγον τῷ Πέτρῳ· 73 μετὰ μικρὸν δὲ προσελθόντες οἱ ἑστῶτες εἶπον τῷ Πέτρῳ· L24 Ἐπ’ ἀληθείας καὶ οὗτος μετ’ αὐτοῦ ἦν, καὶ γὰρ Γαλιλαῖός ἐστιν· Ἀληθῶς ἐξ αὐτῶν εἶ, καὶ γὰρ Γαλιλαῖος εἶ [καὶ ἡ λαλιά σου ὁμοιάζει]· Ἀληθῶς καὶ σὺ ἐξ αὐτῶν εἶ, καὶ γὰρ ἡ λαλιά σου δῆλόν σε ποιεῖ· L25 60 εἶπεν δὲ ὁ Πέτρος· 71ὁ δὲ ἤρξατο ἀναθεματίζειν καὶ ὀμνύναι ὅτι 74 τότε ἤρξατο καταθεματίζειν καὶ ὀμνύειν ὅτι L26 Ἄνθρωπε, L27 οὐκ οἶδα ὃ λέγεις. Οὐκ οἶδα τὸν ἄνθρωπον τοῦτον ὃν λέγετε. Οὐκ οἶδα τὸν ἄνθρωπον. L28 καὶ παραχρῆμα 72 καὶ εὐθὺς Καὶ εὐθέως L29 ἔτι λαλοῦντος αὐτοῦ L30 ἐκ δευτέρου L31 ἐφώνησεν ἀλέκτωρ. ἀλέκτωρ ἐφώνησεν· ἀλέκτωρ ἐφώνησεν· L32 61 καὶ στραφεὶς ὁ κύριος ἐνέβλεψεν τῷ Πέτρῳ, L33 καὶ ὑπεμνήσθη ὁ Πέτρος τοῦ λόγου τοῦ κυρίου ὡς εἶπεν αὐτῷ ὅτι καὶ ἀνεμνήσθη ὁ Πέτρος τὸ ῥῆμα ὡς εἶπεν αὐτῷ ὁ Ἰησοῦς ὅτι 75 καὶ ἐμνήσθη ὁ Πέτρος τοῦ ῥήματος Ἰησοῦ εἰρηκότος ὅτι L34 Πρὶν ἀλέκτορα φωνῆσαι Πρὶν ἀλέκτορα φωνῆσαι Πρὶν ἀλέκτορα φωνῆσαι L35 δὶς L36 σήμερον ἀπαρνήσῃ με τρίς. τρίς με ἀπαρνήσῃ, τρὶς ἀπαρνήσῃ με, L37 62 καὶ ἐξελθὼν ἔξω ἔκλαυσεν πικρῶς. καὶ ἐπιβαλὼν ἔκλαιεν. καὶ ἐξελθὼν ἔξω ἔκλαυσεν πικρῶς. - Red = Luke / Mark / Matthew agreement

- Orange = Luke / Mark agreement

- Blue = Mark / Matthew agreement

- Green = Luke / Matthew minor agreement

L2 The first authentic-looking detail preserved in Luke is his omission of ἀμήν (amēn, “amen”) in Jesus’ prediction. Although ἀμήν is a Greek transliteration of a Hebrew word (see Joshua N. Tilton and David N. Bivin, “LOY Excursus: Greek Transliterations of Hebrew, Aramaic and Hebrew/Aramaic Words in the Synoptic Gospels”), in Mark and Matthew Jesus uses “amen” in a non-Hebraic manner. Generally, Jesus used “amen” as an affirmation, in accordance with normal Hebraic usage, (see Robert L. Lindsey, “‘Verily’ or ‘Amen’—What Did Jesus Say?”), but here Jesus’ prediction is a contradiction of Peter’s boast that he will never forsake Jesus. Thus Luke’s omission of ἀμήν looks more authentic. Lindsey’s hypothesis could account for ἀμήν in Mark and Matthew by supposing that Mark added ἀμήν to the phrase λέγω σοι (legō soi, “I say to you”; L3) because the phrase ἀμήν λέγω σοι (“Amen! I say to you….”) occurs repeatedly throughout the Synoptic Gospels, and that Matthew simply copied ἀμήν from Mark. The version of Jesus’ prediction in John 13:38 repeats ἀμὴν twice.

L5-10 A second authentic-looking detail preserved in Luke is the phrasing of Jesus’ prediction. Whereas according to Mark’s version Jesus says, “before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me thrice,” according to Luke’s version Jesus says, “the rooster will not crow today until you deny three times that you know me.” The phrasing of Luke’s version is similar in structure to the statement in the Mishnah, “and cockcrow had not arrived before the courtyard was full of Israelites [וְלֹא הָיְתָה {מ}קְרוֹת הַגֶּבֶר מַגַּעַת עַד שֶׁהָיְתָה עֲזָרָה מְלֵיאָה מִיִּשְׂרָאֵל]” (m. Tam. 1:2; Kaufmann). Compare the structure of John’s version of Jesus’ prediction: ἀμὴν ἀμὴν λέγω σοι, οὐ μὴ ἀλέκτωρ φωνήσῃ ἕως οὗ ἀρνήσῃ με τρίς (“Amen, amen, I say to you, the rooster will not crow until you deny me three times”; John 13:38).

L6 A third Hebraic detail preserved in Luke is the word σήμερον, also present in Mark. According to Jewish reckoning, the first day of Passover began at sunset on the 14th of Nisan. Thus Jesus could say to Peter that night “you will deny that you know me today.” The version of Jesus’ saying in Luke reads smoothly, but Mark’s version “today, this night before the rooster crows,” is infelicitous. It appears that Mark’s paraphrase of Luke’s Hebraically-structured saying, while attempting to clarify that Peter’s denials would take place in the night, created an awkward sentence. Matthew resolved this difficulty by dropping σήμερον and retaining Mark’s paraphrase in L7.

L8 The most significant Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark is their omission of the second cockcrow. We have seen that cockcrow was an important time marker in first-century Jewish culture. It was not the number of crows, but the moment between night and the break of day that had cultural and religious meaning. Thus Luke and Matthew appear to retain a more culturally authentic tradition, one that is also supported by the Gospel of John. Mark frequently created doublets in his retelling of Gospel stories, and the two rooster crows appear to be an example of this Markan tendency. See David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “LOY Excursus: Mark’s Editorial Style.”

L11 In the opening lines of the description of Peter’s denial we find a Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark to use the phrase ὁ δὲ Πέτρος.

L12 In this line Matthew shows his dependence on Mark, copying the phrase ἐν τῇ αὐλῇ and slightly adjusting Mark’s μία τῶν παιδισκῶν to μία παιδίσκη (cf. Luke’s παιδίσκη in L13). Matthew’s clear dependence on Mark makes the Lukan-Matthean agreement that Peter was sitting (ἐκάθητο) all the more striking.

L13 Here, either Luke paraphrased Mark or Mark paraphrased Luke. In either case, Matt. omits the details in this line.

L14 In Luke’s version the maidservant addresses the people gathered around the fire, presumably people she knows. In Mark and in Matthew she addresses Peter directly. She is also more specific in Mark and Matthew, referring to Jesus by name. Matthew’s dependence on Mark is clear, but in Matthew’s version the maidservant identifies Jesus as a Galilean instead of a Nazarene, as in Mark.

L15 Matthew alone adds ἔμπροσθεν πάντων, perhaps following Mark’s lead in dramatizing the story of Peter’s denial.

L16 Whereas in Luke’s version Peter denies knowing Jesus, in Mark Peter dramatically denies knowing or understanding what the maidservant is saying. Matthew follows Mark in having Peter deny knowing what the maidservant is saying, but note the Lukan-Matthean agreement to write οὐκ οἶδα against Mark’s οὔτε οἶδα.

L17 In vocabulary similar to Mark’s, Matthew agrees with Mark that Peter went outside.

L18 Matthew’s dependence on Mark in the previous line highlights the Lukan-Matthean agreement to omit Mark’s mention of a rooster’s crow after Peter’s first denial. Matthew’s unwillingness to agree with Mark’s two rooster crows while at the same time copying Mark’s text in the previous line probably indicates that there was a strong tradition that Jesus predicted three denials before cockcrow.

L19 The Lukan-Matthean agreement to omit Mark’s πάλιν, a word Lindsey classified as a Markan Stereotype (see Robert L. Lindsey, “Introduction to A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark,” under the subheading “The Markan Stereotypes”), highlights their agreement against Mark that it was not the same maidservant who accosted Peter, but a different (ἕτερος, Luke; ἄλλη, Matt.) person.

L20 This time it is in Luke’s version that Peter is addressed directly, whereas in Mark and Matthew Peter is referred to in the third person. In this line Luke and Mark agree to write ἐξ αὐτῶν. Matthew’s μετὰ Ἰησοῦ τοῦ Ναζωραίου resembles Mark’s μετὰ τοῦ Ναζαρηνοῦ…τοῦ Ἰησοῦ (L14). Mark is here clearly the middle factor: Luke and Mark share verbal agreements, and Mark and Matthew share verbal agreements, but there is no agreement between Luke and Matthew (this is also true in L21, L23, and L27). Either Luke and Matthew independently selected words from Mark, or Mark paraphrased Luke and then Matthew paraphrased Mark. It is the Lukan-Matthean agreements against Mark that undermine the theory of Markan Priority.

L22 Note the Lukan-Matthean agreement of vocabulary for “man” and “not,” but the sentences have a different sense: according to Luke, Peter denies being one of Jesus’ disciples; in Matthew’s version Peter denies knowing the man (i.e., Jesus).

L24 The bracketed words in Mark are not present in all ancient manuscripts. If the bracketed words in Mark are original then we can understand the reason for Mark’s paraphrase. In Luke, Peter is identified as a disciple because he is a Galilean. Mark explains how the person in Luke’s version discovered Peter’s Galilean origin—his accent gave him away. Matthew dropped the identification of Peter as a Galilean (having already referred to Jesus as a Galilean in L14), but this omission makes the line of reasoning incomprehensible. How can Peter’s manner of speaking prove that he is a disciple? It is Peter’s Galilean origin that is the key to the observer’s logic.

L25 Mark often dramatizes the stories he tells, and here it is likely that Mark invented Peter’s blaspheming and swearing, a detail that Matthew took over. Note Matthew’s characteristic τότε. See Randall Buth, “Matthew’s Aramaic Glue.”

L26 Here, Luke writes ἄνθρωπε (anthrōpe, “man”), as in L22 above.

L28 Mark uses his stereotypical εὐθύς (evthūs, “immediately”) opposite Luke’s παραχρῆμα (parachrēma, “immediately”). On Mark’s repeated use of εὐθύς, see Robert L. Lindsey, “Introduction to A Hebrew Translation of the Gospel of Mark,” under the subheading “The Markan Stereotypes.” Matthew replaces εὐθύς with εὐθέως (evtheōs, “immediately”). Compare John 18:27: καὶ εὐθέως ἀλέκτωρ ἐφώνησεν (kai evtheōs alektōr efōnēsen, “and immediately a rooster crowed”).

L30, L35 Again we note the Lukan-Matthean agreement to omit Mark’s “for a second time.”

L32 This sentence is unique to Luke.

L33 Note the similarity of structure between Luke’s τοῦ λόγου τοῦ κυρίου (“the word of the Lord”), and Matthew’s τοῦ ῥήματος Ἰησοῦ (“the saying of Jesus”). Despite utilizing Markan vocabulary, Matthew’s sentence resembles Luke’s, perhaps indicating that Matthew attempted to paraphrase the pre-synoptic source he had in common with Luke by using words gleaned from Mark.

L36 Here, only Luke retains the Hebraic σήμερον (cf. L6).

L37 The concluding words of this pericope show an astounding word-for-word Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark: καὶ ἐξελθὼν ἔξω ἔκλαυσεν πικρῶς (“and going outside he wept bitterly”). Note the similarity to Mark’s phrase καὶ ἐξῆλθεν ἔξω εἰς τὸ προαύλιον in L17. It strains the imagination to suppose that two authors independently decided to take a phrase from an earlier portion of Mark’s pericope and use it as their conclusion to the story of Peter’s denial. It is much more plausible to suppose that a single author (Mark) composed a unique conclusion, and that the conclusion in Luke and Matthew reflects the wording of a pre-synoptic source. ↩

Comments 3

Hello Joshua, can you help me understand why this time marker was important?

“It was not the number of crows, but the moment between night and the break of day that had cultural and religious meaning.”

I guess I would have assumed that what would have been more important was when the sun set, because that would have marked when the new day started. Why would the first break of light matter religiously?

Author

Joshua,

You are quite correct that sunset is an important time marker in Judaism, separating one day from the next. Cockcrow served a different function: to distinguish between nighttime and daytime. This was an important time marker because certain commandments had to be completed before the ending of the night (e.g., consuming the Passover lamb, reciting the evening Shema). Both time markers are important, but they distinguish between different things. Sunset separates days on a calendar, cockcrow separates time within a given day.

Perfect, thank you. That totally makes sense now.