How to cite this article: Mendel Nun, “Has the Lost City of Bethsaida Finally Been Found?” Jerusalem Perspective 54 (1998): 12-31 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/905/].

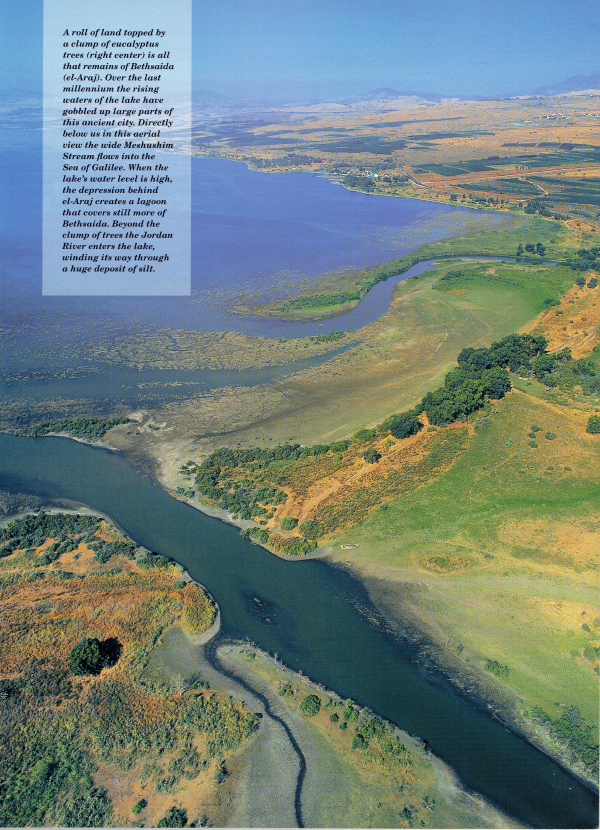

Mendel Nun and JP editor David Bivin working at Nun’s kitchen table. Bivin questions Nun about his “Has Bethsaida Finally Been Found?” as they prepare it for publication. Photographed by Joel Ben-Yosef. Most people think the search for Bethsaida is over. Archaeological excavations have taken place at et-Tell for ten years, and they continue this summer. Many scholars, too, have accepted Bethsaida Excavations Project director Dr. Rami Arav and his associates’ conclusion that et-Tell is the Bethsaida of the New Testament. So has the Israeli government. Since 1989 Bethsaida has been located at et-Tell on all maps produced by the State of Israel. Even the Vatican has accepted this identification: the Vatican’s committee on holy sites has recognized et-Tell as Bethsaida. Among archaeologists, however, there is growing skepticism about the claims of the et-Tell expedition. Mendel Nun, an authority on the Sea of Galilee and its environs, believes Bethsaida was located at el-Araj, a site on the Sea of Galilee’s northeastern shore near the Jordan River—the lake’s ancient fishing villages were always located on its shores. Nun rejects outright Arav’s contention that he has found the ancient site of Bethsaida. Nun thinks the et-Tell excavation results do not support Arav’s claims, but, in fact, disprove them. Nun calls for a thorough excavation at the el-Araj site, where surface remains are especially impressive. Now Nun has written his objections to the et-Tell identification in detail, and Jerusalem Perspective is privileged to publish his article. We commissioned artist and photographer Janet Frankovic to photograph remains at el-Araj in 1995. This year we sent master photographer Joel Fishman on assignment to el-Araj. In our opinion, Frankovic and Fishman’s photographs, together with photographs from the archives of Beit Ha-Oganim, the Sea of Galilee museum at Kibbuts Ein Gev, and two stunning photographs we obtained from aerial photographers Duby Tal and Moni Haramati of Albatross, plus drawings by Helen Twena, provide the necessary graphic accompaniment to Nun’s breakthrough article. I hope you, our readers, enjoy this article. Bethsaida is one of the few places visited by Jesus that is mentioned by name in the New Testament. Its identification is extremely important to students of the Gospels, and I think Nun’s article is a significant step forward in finding this lost city. Keeping our readers informed with the most accurate and up-to-date information about textual and archaeological discoveries in Israel relating to the Gospels is the aim of Jerusalem Perspective. —David Bivin (editor-in-chief) |

The fishermen’s village of Bethsaida on the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee is one of the most important holy sites of the Christian world. Yet the question of its exact location in Jesus’ time has long been a troubling and disputed issue.

Some basic clues are provided by the Gospels. According to John, three of Jesus’ apostles—Simon Peter, Andrew and Philip—came from Bethsaida (John 1:44; 12:21). We also know that Jesus performed miracles in Bethsaida: When a blind man was brought to him, Jesus took him to the outskirts of the village and there healed him (Mark 8:22-26). The miracle of the loaves and fish was performed near Bethsaida, when from two fish and five loaves Jesus provided ample food for a multitude of five thousand (Luke 9:10-17).

The site of Bethsaida was certainly somewhere on the northeastern shore of the Sea of Galilee, near the inlet of the Jordan River. Opposite Bethsaida, on the northwestern shore about four kilometers across the water was the ancient city of Capernaum. Four kilometers north of Capernaum was the city of Chorazin. Most of Jesus’ Galilean ministry took place in the region of these three cities; hence the term “Evangelical Triangle.” Of the three cities, Capernaum, with its fishing suburb Tabgha, was the very center of Jesus’ activities. From Capernaum he traveled to other towns and villages in Galilee, and from Capernaum’s harbor he sailed to cities on the other side of the lake.

Capernaum is mentioned thirteen times in the Gospels. Jesus stayed there with Simon Peter, who lived with his family in the house of his mother-in-law (Matt. 8:14-15; Mark 1:29-31; Luke 4:38-39). From this we may understand that because of the sons’ marriages, the family had moved from Bethsaida to Capernaum. Thus we see that family and fishing relations connected the two cities of Bethsaida and Capernaum.

Opinions differ as to the length of Jesus’ stay in Capernaum. There are those who believe it was a short time, while others argue that it extended to three years. The sayings and parables of Jesus point to an intimate knowledge of the lake and of the fishing profession, indicating that he stayed in this region for a significant length of time. At Capernaum he healed the sick and performed miracles, and preached in the synagogue on the Sabbath (Matt. 8:16-17; Mark 1:21-28, 32-34; Luke 4:31-37, 40-41). Therefore, Capernaum is known as the “City of Jesus.”

Next to Jerusalem and Capernaum, the city most frequently mentioned in the Gospels is Bethsaida. However, we know nothing of Jesus’ works there, except for the miracle of the healing of a blind man. But his presence in Bethsaida was significant on another level: Herod Antipas, the ruler of Galilee, viewed Jesus with suspicion fearing he would stir political unrest among the Jews in the area, whereas Philip, the more liberal ruler of the neighboring Golan, which had a mixed population, was not troubled by Jesus’ activities.

Jesus’ work in Chorazin is not mentioned in the Gospels. Since most of the Jewish inhabitants of the Evangelical Triangle did not accept his teachings, he reproached them:

Woe to you, Chorazin! Woe to you, Bethsaida! For if the mighty works done in you had been done in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented long ago in sackcloth and ashes. (Matt. 11:21; Luke 10:13)

From this we may conclude that Jesus performed his “mighty works” in both Chorazin and Bethsaida, even though we are not explicitly told this.

Paid Content

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be logged in to access this content: Login

If you do not have a paid subscription, please consider registering as a Premium Member starting at $10/month (paid monthly) or only $5/month (paid annually): Register

One Time Purchase Rather Than Membership

Rather than purchasing a membership subscription, you may purchase access to this single page for $1.99 USD. To purchase access we strongly encourage users to first register for a free account with JP (Register), which will make the process of accessing your purchase much simpler. Once you have registered you may login and purchase access to this page at this link:

![Mendel Nun [1918-2010]](https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/wp-content/uploads/userphoto/18.jpg)

Comments 2

One of my pleasures of life was meeting Mendel Nun at Kibbutz Ein-Gev at the fishing museum.

The official name of this unique museum, now directed by Yoel Ben-Yosef, is The Sea of Galilee Fishing Museum. To learn more about it, read my essay “Sea of Galilee Museum Opens Its Doors,” on this website.