This article is Joshua Tilton’s personal reflection based on his work on the Sending the Twelve: Conduct on the Road pericope for the Life of Yeshua project.

I am grateful to be living in a generation that has demonstrated a growing sensitivity toward issues of racial justice.[1] The struggle of minority groups to attain equal treatment under the law and to enjoy equal respect in society is commendable. We are all indebted to minority groups who have raised their voices in protest against inequality, not only for making our own societies more humane, but also for helping us to look back at our histories and at our sacred texts from a new—and I hope more inclusive—point of view. This blog is a tiny tribute to the ongoing struggle for racial justice and harmony in our world.

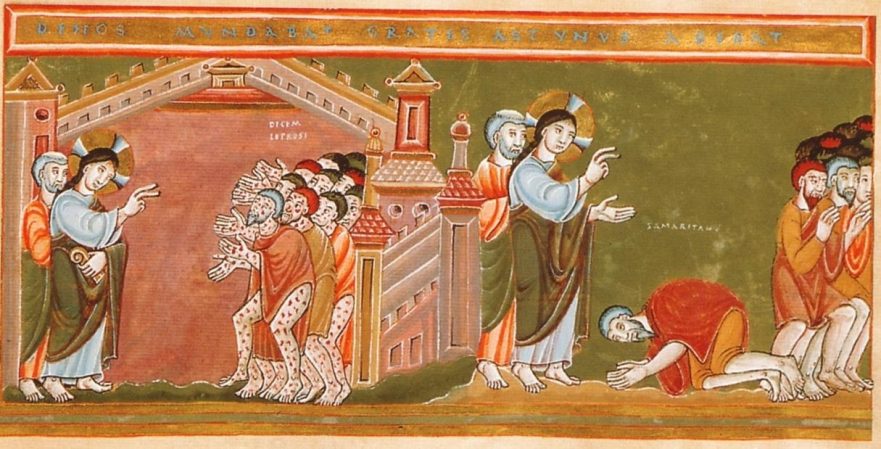

In our recent attempt to propose a Hebrew reconstruction of Jesus’ instructions to his twelve apostles (see Sending the Twelve: Conduct on the Road), David Bivin and I were confronted with a racially sensitive issue. According to the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus told the apostles not to enter any city of the Samaritans (Matt. 10:5). Reconstructing Jesus’ words in Hebrew raised an uncomfortable question that, as far as we are aware, has never before been considered by New Testament scholars. The question is: What Hebrew word did Jesus use to refer to the Samaritans? This is a sensitive question because, of the two Hebrew alternatives, the more common term in ancient Jewish sources is a racial slur.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

Notes

- My optimistic view that our generation has demonstrated a growing sensitivity toward issues of racial justice in no way negates the reality of continued incidents of violence, hatred or discrimination. Neither do I wish to gloss over the very real pain endured by those who have experienced the cruel effects of racial injustice. I am merely expressing a hopeful view that sensitivity concerning these issues may be growing. If that sensitivity is to continue growing and bear meaningful fruit in our societies, then, of course, it must be carefully tended and nurtured. I hope that I may continue to learn and grow and be open to correction when I demonstrate my own ignorance and prejudices.[↩]

Comments 1

Superbly researched and beautifully written; a thought-provoking and timely article, especially in view of recent world events. Thank you, Joshua.