For most of its existence Christianity has struggled with its Hebraic and Jewish heritage. To complicate matters, Hebraicists have always stood out as a rare breed in the Christian fold. The shortage of people learned in Hebrew and Jewish literary sources has left its marks on the life and history of the Church.

For a long time Jews have been discouraging people from pronouncing God’s Hebrew name, which is represented by the four consonants yod-hey-vav-hey (YHVH).[1] Their efforts were probably motivated in large measure by a sense of awe (cf. Exod. 3:14-15) and a desire to guard against overfamiliarity with God (cf. Exod. 20:7).

Sometime about the 8th century A.D., Jewish scribes began adding pointing (or vowels) to the consonants of the Hebrew Scriptures. On the one hand, the vowels helped preserve the text’s traditional vocalization, and they facilitated pronunciation. On the other hand, Jewish scribes did not want readers to pronounce God’s name. To solve the dilemma, they borrowed the vowels from adonai (Hebrew for “Lord”) and inserted them among the consonants of YHVH. The result was a funny-looking Hebrew word. The foreign vowels served as a deterrent against pronouncing God’s personal name. The strategy worked brilliantly as long as Jews were the ones reading the pointed consonants.

Perhaps as early as 1100 A.D. Christians began pronouncing the funny word. In doing so, they unwittingly gave God a new name: Jehovah. Passing over the irony of the blunder, the editors of one popular Bible dictionary assessed the situation in this terse sentence: “[Jehovah’s] appearance in the KJV was the result of the translators’ ignorance of the Hebrew language and customs.” In addition to the KJV translators, the ASV translators also adopted the new name. Because of the influence of such English translations, Christian hymn writers celebrated the name Jehovah.[2] Moreover, even writers of contemporary praise music continue to include Jehovah in their lyrics. Consider, for example, “Jehovah Jireh” and “O My Soul, Bless Thou Jehovah.”

This was not the first name coined by Christians unaware of Jewish scribal habits. Already in the first century B.C., when copying biblical manuscripts, some scribes wrote YHVH in an archaic form of Hebrew script known as Paleo-Hebrew. They, too, were probably motivated by reverence for the special name that God had revealed to Moses and a desire not to transgress the third commandment.

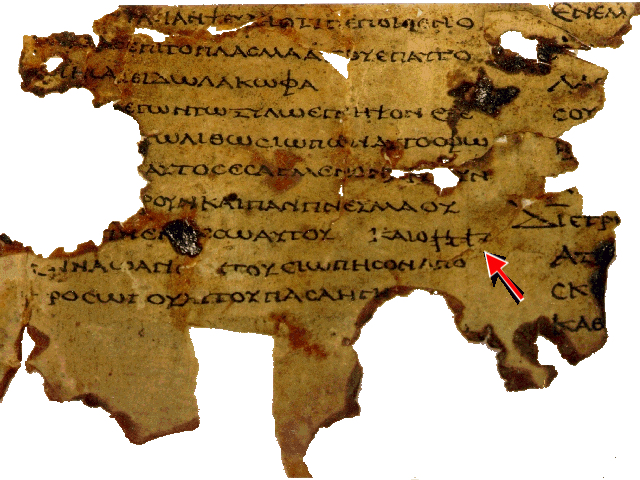

A few of the Hebrew Dead Sea Scrolls preserve examples of this practice. Interestingly, Jewish scribes employed this same strategy even when copying Greek manuscripts. In a cave at Nahal Hever archaeologists found a Greek version of the Minor Prophets that Jews had hidden during the second revolt against Rome (132-135 A.D.). The scribe (or translator) who produced this scroll wrote YHVH in Paleo-Hebrew script. The old Hebrew letters stand out from the Greek script. Incidentally, the church father Origen (c. 185-254) mentioned seeing such scrolls.

Of particular interest is a papyrus known as Fouad 266. This pre-Christian, Greek fragment of Deuteronomy contains examples of YHVH written in Hebrew script. The script, however, is not the Paleo-Hebrew script, but the common square script that is still in use today. The church father Jerome (c. 342-420) indicated in his writings that he had seen examples of both script types in Greek scrolls.

When reading scrolls that contained the Paleo-Hebrew script, a Greek reader had little opportunity to blunder, because the script looked like indecipherable scribble; however, when a Greek reader encountered YHVH written in the more modern square script, the chance for error increased substantially. According to Jerome, those who were unfamiliar with Jewish customs tried to pronounce the Hebrew letters as if they were Greek letters. The result was quite a howler: they pronounced YHVH as PIPI![3] All of us can be grateful that no songs celebrating “PIPI of Hosts” found their way into the pages of our hymnals. I might add that after being called PIPI for several centuries, God probably welcomed the name Jehovah.

As humorous as the origins of PIPI and Jehovah may be, the short supply of Hebraicists in the modern Church is no laughing matter. Alleviating the shortage would certainly produce widespread benefits. A few of them would be:

- Better integration of the Hebrew Scriptures into our Christian preaching and teaching;

- English translations of the New Testament reflecting a greater sensitivity to the Greek text’s Jewish component;

- a deeper reservoir of Hebraic and Judaic expertise from which organizations like the United Bible Societies and Wycliffe Bible Translators could draw, which in turn would make possible more accurate Bible translations for millions of people living in the Third World; and

- a more mature handling of the vexing issues surrounding Christianity’s historical and theological relationship with Judaism—which could only improve the relationship between the Church and Synagogue. In the end, if we were to support—both verbally and financially—university students pursuing degrees in Judaic studies, our efforts at preaching, teaching and translating the Bible would be strengthened within a few decades.

To write this article, I have relied upon the following sources:

- The Anchor Bible Dictionary (chief ed. D. N. Freedman; 6 vols.; New York: Doubleday, 1992), 6:1011.

- Harper’s Bible Dictionary (general ed. P. J. Achtemeier; San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985), 1036.

- Ernst Wurthwein, The Text of the Old Testament (trans. E. Rhodes; 2nd ed.; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995), 4, 21, 158, 190, 192.

- N. R. M. De Lange, Origen and the Jews (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1976), 59, 181.

- [1] For a discussion of the pronunciation, meaning and avoidance of God’s personal name, see David Bivin, “‘Jehovah’—A Christian Misunderstanding,” Jerusalem Perspective 35 (Nov./Dec. 1991): 5-6; ibid., “Meaning of the Unutterable Name”: 6; and idem, “Jesus and the Oral Torah: The Unutterable Name of God,” Jerusalem Perspective 5 (Feb. 1988): 1-2. See also Ray Pritz, “The Divine Name in the Hebrew New Testament,” Jerusalem Perspective 31 (Mar./Apr. 1991): 10-12; and David Bivin, “The Fallacy of Sacred Name Bibles,” Jerusalem Perspective 35 (Nov./Dec. 1991): 7, 12. ↩

- [2] Among the hymns whose writers used the name Jehovah are: “Before Jehovah’s Awe-Full Throne” and “The Lord Jehovah Reigns” (Isaac Watts, 1674-1748); “Sing to the Great Jehovah’s Praise” (Charles Wesley, 1707-1788); and “Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah” (William Williams, 1717-1791). ↩

- [3] Like English, Greek is read from left to right. Hebrew, on the other hand, is read from right to left. When encountering the four Hebrew consonants representing God’s name, a Greek reader would read them in reverse order: heh-vav-heh-yod (HVHY). He then read the heh as pi, the vav as iota, the heh as pi, and the yod as iota. Pi-Iota-Pi-Iota spells PIPI (pronounced in English as Pee-Pee). ↩

Comments 4

That was very interesting. Thanks. Do you have any other articles here on Jehovah and the Tetragrammaton? Doing a search, I did not get any results.

In one place you mentioned that “the editors of one popular Bible dictionary assessed the situation in this terse sentence: “[Jehovah’s] appearance in the KJV was the result of the translators’ ignorance of the Hebrew language and customs.”” At that point, the editors of the Bible dictionary may be dealing from a bit of their own ignorance. Jehovah had appeared in English Bibles since William Tyndale translated the Pentateuch in 1530. It was not a creation of the King James translators.

Thanks again. Have a great day.

Thanks, Robert, for your inquiry. We’ve had some trouble with the JP search engine lately, but it’s up and running again now, so if you try searching “Tetragammaton” again you should get some results. –JP

Shalom!

Thank you for the excellent article, Joseph! I had NO idea about the PIPI phase of our early Church history; I was never taught that in church. Wow. Burr! Why PIPI was discontinued but not Jehovah is, I guess, a question for another time (unless someone wants to answer it after my main question :)

The main reason I sought out this article is that a debate is brewing with a friend over the proper pronunciation of the Tetragrammaton, my friend insisting on “Jehovah.” I pulled out David Bivin’s excellent book, _New Light on the Difficult Words of Jesus_, Chapter 8, subsection, _Jehovah: a Christian Misunderstanding_, to make sure my argument will be clear and correct but became confused by his comments on the matter. I’m hoping that someone can clarify them for me here.

David echos Joseph, saying: “Until the early Middle Ages, Hebrew was written without vowels. But by the sixth century A.D. there were only a few native Hebrew speakers left, and most Jews had only a passive knowledge of Hebrew. It was then that a system of vowel signs was developed by the Masoretes, the Jewish scholars of the period, to aid the reader in pronunciation.

So far we’re all on the same page and I’m not confused. But David goes on to say:

“In accordance with the custom observed since the third century B.C., when reading or reciting Scripture, they superimposed the vowel signs of the word Adonai upon the four consonants of God’s name. This was to remind the reader he should not attempt to pronounce the unutterable name. Thus YHWH would be read as Adonai.”

This seems like a contradiction, and thus, my confusion. I.e., were Hebrew vowel symbols around since the third century B.C. but just not used, or were they developed in the Middle Ages by the Masoretes?

Any help would be most appreciated!

Shalom and God bless…

Gary Zoren

Hi Gary,

We see how the issue can be confusing. What David Bivin was saying is that the vocalization represented by the pointing of the Masorites reflects a tradition much older than the pointing system itself. In other words, there had been a long tradition of pronouncing “Adonay” whenever the Tetragrammaton appeared in the text. When the pointing system was developed the Tetragrammaton was pointed in such a way as to represent that preexisting tradition. As a result the vocalization (pointing) of the Tetragrammaton does not match the consonantal text.

It may be helpful to know that the Tetragrammaton is not the only example in the Masoretic Text (MT) where the vocalization does not match the consonants. The numerous discrepancies between the written and vocalized traditions are referred to as qere (“read”) and ketiv (“written”). In all such instances the pointing disagrees with the consonantal text. An example is found in Deut. 28:23 where the consonantal text reads ובעפלים (“and with tumors”) but where the pointing וּבַעְפֹלִים indicates a different word entirely: וּבַטְּחוֹרִים (“and with hemorrhoids”).

It should be understood that the Masoretic Text represents two distinct traditions: a written tradition (consonants) and a vocalized tradition (pointing). For the most part those traditions agree with one another, but not always. Both traditions are considered to be sacred, and so they are allowed to coexist, even when they contradict one another.

Hope that helps,

—JP