How to cite this article: R. Steven Notley, “Anti-Jewish Tendencies in the Synoptic Gospels,” Jerusalem Perspective 51 (1996): 20-35, 38 [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/2773/].

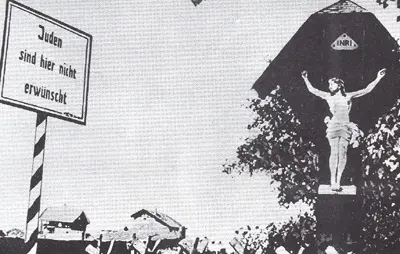

Was Jesus anti-Semitic? Did he actually reject particular aspects of his own Jewishness? Some verses in the Gospels do appear anti-Jewish. However, did these anti-Jewish tendencies begin with Jesus and his followers or did they originate elsewhere? A thorough examination of the Gospels reveals that not all of the accounts are identical in their presentation of Jesus and his contemporaries. Each of the writers has left his own individual style on his composition. In this study we will carefully consider the differing accounts in hope of determining whether anti-Jewish or anti-Judaistic sentiments belonged to Jesus and his first followers. For the purposes of the study I have ordered the Gospels according to their increasing anti-Jewish sentiment.

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

Conclusion

In this brief study I have tried to demonstrate that at its earliest stage the church was marked by a relative freedom from anti-Jewish sentiment. However, the natural evolution of early Christianity from its Jewish context brought tensions that have penetrated even into the early strata of the synoptic tradition. Mark amplified the conflict between Jesus and his contemporaries. Mark’s primary motives were to present Jesus as an abandoned Messiah. For the most part, he possessed no anti-Jewish penchant.

The gospel of Matthew, on the other hand, possesses a number of anti-Jewish statements that may be the work of a later Gentile scribe. These revisions paint the entire Jewish nation as culpable for the death of Jesus. In the scribe’s thinking, Israel had been rejected in lieu of the Gentile church. These ideas reflect little of Jesus’ own thinking or experience. Ironically, Jesus himself knew of some in his own day who saw the people of Israel as rejected and viewed themselves as the sole custodians of the holy Scriptures and the holy place. To these first-century supplanters—the Samaritans—Jesus’ response was simple but categorical: “Salvation is of the Jews” (John 4:22).

For readers’ reactions to this article and responses from the author, R. Steven Notley, and the editor, David Bivin, see these Readers’ Perspective posts: “Disgusting Illustrations Distract from Worthy Content!“; “If a Jew mistreats a Jew, does that make him anti-Semitic?“; “What is the Jerusalem School’s hermeneutical criterion?“; and “Mark’s Account of the Cleansing of the Temple: Literary Device or Historical Fact?“

Comments 1

Author

Chris, first thank you for making the effort to post. However, if you are not going to read the article, then there is little use in my responding b/c you are not really commenting about my article but simply letting off steam about something that you heard or read elsewhere. Cheers, Steven!