How to cite this article:

David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2021) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/20146/].

Matt. 3:11-12; Mark 1:7-8; Luke 3:15-17[1]

Updated: 21 March 2024

וַיַּחְשְׁבוּ הָאֻכְלוּסִים בְּלִבָּם יוֹחָנָן הוּא הַמָּשִׁיחַ וַיַּעַן יוֹחָנָן אוֹתָם לֵאמֹר אֲנִי מַטְבִּיל אֶתְכֶם בַּמַּיִם וַהֲרֵי בָּא אַחֲרַי מִי שֶׁאֵינִי כָּשֵׁר לְהַתִּיר לוֹ רְצוּעַת מִנְעָלָיו הוּא יַטְבִּיל אֶתְכֶם בָּרוּחַ וּבָאֵשׁ מִי שֶׁהָרַחַת בְּיָדוֹ וְיָבוֹר אֶת גּוֹרְנוֹ וְיַכְנִיס אֶת הַחִטִּים לְאוֹצָרוֹ וְהַקַּשׁ יִשְׂרֹף בְּאֵשׁ תָּמִיד

The people in the crowds were thinking, “Yohanan the Immerser must be the messianic priest!”

But Yohanan replied, “I immerse you in water, but be aware: Someone is coming after me for whom I am unfit even to undo his sandal straps. When he comes he will immerse you in wind and fire. Already this someone has his winnowing shovel in his hand, and he intends to purify his threshing floor. The wheat he will store in his storeroom, but the stubble that remains on the threshing floor he will burn in the flames of the altar.”[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse, click on the link below:

Story Placement

Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse is the only specimen of direct speech attributed to John the Baptist in the Gospel of Mark. As a result, in Mark’s Gospel the only statement the Baptist is permitted to make is that his own water immersions are about to be supplanted by a Mightier One who will immerse his audience in the Holy Spirit. Clearly, the author of Mark offers a distorted picture of the Baptist’s message, for had John solely proclaimed the coming of a Mightier One with a better baptism than his own, there would have been no reason to receive John’s immersion. Thus, the Lukan and Matthean inclusion of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse within a larger cluster of the Baptist’s sayings is inherently more probable than the placement of this pericope as an isolated saying in the Gospel of Mark.

In the Gospel of Matthew, Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse is presented as though it were the continuation of John’s condemnation of the Pharisees and Sadducees (cf. Matt. 3:7). This placement has the jarring result that the Pharisees and Sadducees are thereby included among those whom John claims to have baptized (“I am baptizing you”; Matt. 3:11).[3] If the Pharisees and Sadducees had been willing participants in John’s water immersions, we must ask what cause the Baptist had for castigating them. The best explanation is that the audience against which Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse is directed in Matthew is unrealistic, and undoubtedly due to the author of Matthew’s tendentious insertion of the Pharisees and Sadducees into the introduction of his version of Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance.[4]

The placement of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse in Luke’s Gospel, by contrast, makes good sense. There it forms part of John’s address to the crowds, coming in response to their speculations about the Baptist’s role in the divine economy. Moreover, we have found that the author of Luke, throughout his third chapter, followed the order of pericopae as they appeared in his source, the Anthology (Anth.). We have, accordingly, accepted Luke’s pericope order in our reconstruction of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

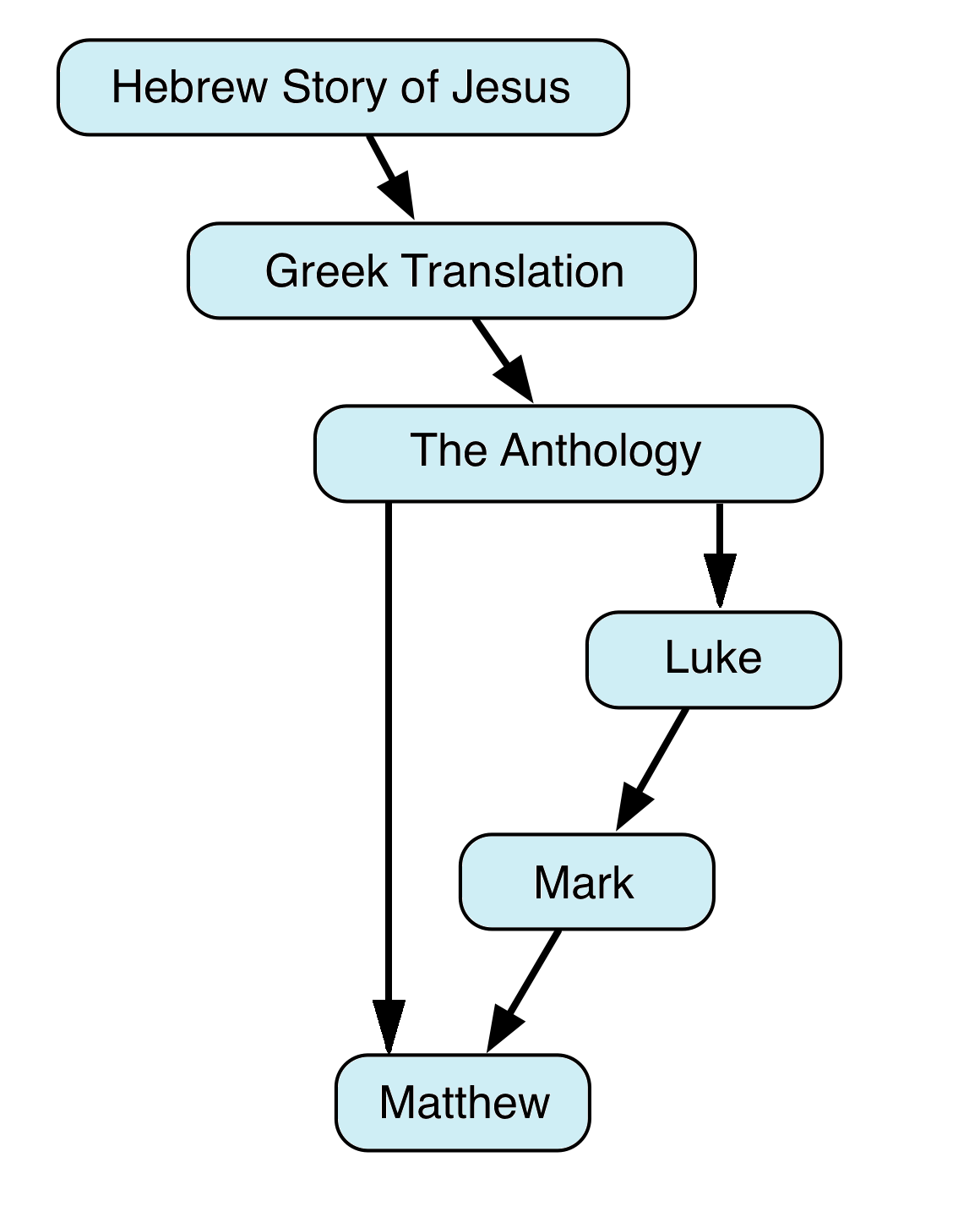

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

Despite evidence of a fair amount of redactional activity in the opening verse of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse (Luke 3:15), the numerous Lukan-Matthean minor agreements against Mark in this pericope, as well as the overall ease with which Luke’s version reverts to Hebrew, suggest that the author of Luke copied Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse from his Hebraic-Greek source, Anth.[5]

Despite evidence of a fair amount of redactional activity in the opening verse of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse (Luke 3:15), the numerous Lukan-Matthean minor agreements against Mark in this pericope, as well as the overall ease with which Luke’s version reverts to Hebrew, suggest that the author of Luke copied Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse from his Hebraic-Greek source, Anth.[5]

The author of Mark based his version of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse on Luke’s, making characteristic changes such as inversion of word and sentence order, addition of colorful detail, and (counterintuitively) omission of entire statements.

The author of Matthew combined the short Markan form with the fuller Anth. account to produce his version of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse.[6]

Versions of John the Baptist’s sayings contained in Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse are also included in Acts and the Gospel of John.[7] In the opening chapter of Acts the risen Jesus is reported as saying:

Ἰωάννης μὲν ἐβάπτισεν ὕδατι, ὑμεῖς δὲ ἐν πνεύματι βαπτισθήσεσθε ἁγίῳ οὐ μετὰ πολλὰς ταύτας ἡμέρας

John immersed in water, but in a few days you will be immersed in a holy spirit. (Acts 1:5)

It should be noted that Jesus’ promise of the Holy Spirit merely alludes to John the Baptist’s saying, it is not a direct quotation,[8] and there is no reason to suppose that the fulfillment of Jesus’ promise as described in Acts 2 bears a direct relationship to what John the Baptist had in mind when he contrasted his water immersions with the immersion to be administered by the Someone coming after him. Indeed, it is characteristic of Jesus to put a new twist on a concept he inherited from others.

Elsewhere in Acts we find Paul quoting John the Baptist:

ὡς δὲ ἐπλήρου Ἰωάννης τὸν δρόμον, ἔλεγεν· τί ἐμὲ ὑπονοεῖτε εἶναι; οὐκ εἰμὶ ἐγώ· ἀλλ᾿ ἰδοὺ ἔρχεται μετ᾿ ἐμὲ οὗ οὐκ εἰμὶ ἄξιος τὸ ὑπόδημα τῶν ποδῶν λῦσαι

But as John was completing his race, he was saying, “What do you think I am? It is not I. But, behold, one is coming after me, the shoe of whose feet I am not worthy to untie.” (Acts 13:25)

Bovon suggested that the fact that parts of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse were quoted on separate occasions in Acts is evidence that the sayings originally had an independent existence, and that it was only at a later stage that these sayings attributed to the Baptist were combined into a single discourse unit.[9] But it is the universal practice of orators to cite only the parts of a well-known quotation that serve her or his purpose, even when doing so substantially changes the quotation’s original meaning and/or ignores its original context. Therefore, we do not find Bovon’s opinion that different parts of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse were quoted on separate occasions to be convincing.

In the Gospel of John the Baptist is quoted as saying:

ἐγὼ βαπτίζω ἐν ὕδατι· μέσος ὑμῶν ἕστηκεν ὃν ὑμεῖς οὐκ οἴδατε, ὁ ὀπίσω μου ἐρχόμενος, οὗ οὐκ εἰμὶ [ἐγὼ] ἄξιος ἵνα λύσω αὐτοῦ τὸν ἱμάντα τοῦ ὑποδήματος

I immerse in water. Among you stands one whom you do not know, the one coming after me, the strap of whose shoe I am not worthy to untie. (John 1:26-27)

The form of the Baptist’s saying preserved in the Fourth Gospel is a secondary reworking of an earlier version. This is evident from the fact that John’s assertion “I immerse in water” serves no purpose in its Johannine context; it neither answers the question posed in John 1:25 (“Why, then, do you immerse if you are neither the Messiah, nor Elijah, nor the Prophet?”) nor distinguishes the Baptist from the one coming after him, since this coming one is not said to administer an immersion of any kind.[10] We believe that Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse, especially in its Lukan and Matthean versions, preserves the earliest and most accurate form of John the Baptist’s prophecy of the Someone coming after him.

Crucial Issues

- What was the identity of the figure who would administer the baptism greater than John’s?

- What was the nature of the baptism the eschatological figure would administer?

Comment

L1-5 Although the Greek of Luke 3:15 resists retroversion to Hebrew, we believe it is more likely that the author of Luke reworked the introduction to Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse than that he created it ex nihilo.[11] First, having determined that Yohanan the Immerser’s Exhortations (Luke 3:10-14) derived from Anth., some kind of transition introducing Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse would have been necessary. Otherwise, the Baptist’s prophecy of Someone coming after him would have lacked a context. Second, despite evidence of Greek polishing in Luke 3:15, this verse also contains the Hebraic phrase “thinking in their hearts,” which suggests that behind Luke’s introduction there stood a Hebrew original.

The people’s hesitant speculation, “Perhaps he might be the Messiah,” expressed in difficult-to-reconstruct-Greek, may hint at the reason the author of Luke decided to rework the introduction to Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse. The Anthology may have contained what the author of Luke deemed to be too strong an affirmation of John the Baptist’s messianic status. Anth.’s version may have simply quoted the crowds as thinking, “John: he’s the Messiah!”

In any case, the author of Luke’s reworking of the introduction to Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse is similar to his reworking of the transition between A Voice Crying and Yohanan the Immerser Demands Repentance (Luke 3:7).[12]

L1 προσδοκῶντος δὲ τοῦ λαοῦ (Luke 3:15). The use of the genitive absolute construction (“while the people were expecting”)[13] and the change in audience from “the crowds” (Luke 3:7, 10) to “the people” (Luke 3:15)[14] suggest that L1 is the product of Lukan redaction.[15] The disproportionately high frequency of the verb προσδοκᾶν (prosdokan, “to expect,” “to wait”) in the writings of Luke compared to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark points in the same direction.[16] Since the main idea of Luke 3:15 can be expressed in Hebrew without reconstructing L1, we have omitted it from GR and HR.

L2 καὶ διελογίσαντο οἱ ὄχλοι (GR). While Luke’s genitive absolute construction (“while everyone was conversing”) is likely redactional, the combination of διαλογίζεσθαι (dialogizesthai, “to consider,” “to converse”) with “in their hearts” (L3) could easily have been adopted from Luke’s source (Anth.),[17] since “thinking in the heart” is a common Hebrew idiom (see below, Comment to L3).[18] Perhaps instead of Luke’s genitive absolute a simple καί + aorist construction stood in Anth. Likewise, instead of “the people” or “everyone” as the subject, perhaps Anth. referred once more to “the crowds.” On the basis of these speculations we have adopted καὶ διελογίσαντο οἱ ὄχλοι (“and the crowds conversed”) for GR in L2.

וַיַּחְשְׁבוּ הָאֻכְלוּסִים (HR). In LXX the verb διαλογίζεσθαι is not particularly common, but where it does occur it usually appears as the translation of חָשַׁב (ḥāshav, “think,” “consider”).[19] Instances of חָשַׁב in MT were more frequently rendered with λογίζεσθαι (logizesthai, “to reckon,” “to think”) than with the compound form διαλογίζεσθαι. Nevertheless, διαλογίζεσθαι is among the more common renderings of חָשַׁב in LXX.[20]

On reconstructing ὄχλος (ochlos, “crowd”) with אֻכְלוּס (’uchlūs, “crowd”), see Widow’s Son in Nain, Comment to L4.

L3 ἐν ταῖς καρδίαις αὐτῶν (GR). We have accepted “in their hearts” for GR not only because this phrase easily reverts to Hebrew, but also because “to think in the heart” is a Hebraic expression, examples of which include:

וְאִישׁ אֶת רָעַת רֵעֵהוּ אַל תַּחְשְׁבוּ בִּלְבַבְכֶם

And each of you must not devise [תַּחְשְׁבוּ] the evil of his neighbor in your heart [בִּלְבַבְכֶם]. (Zech. 8:17; cf. Zech. 7:10)

καὶ ἕκαστος τὴν κακίαν τοῦ πλησίον αὐτοῦ μὴ λογίζεσθε ἐν ταῖς καρδίαις ὑμῶν

…and do not devise [λογίζεσθε] evil in your hearts [ἐν ταῖς καρδίαις ὑμῶν] each against his neighbor…. (Zech. 8:17; NETS; cf. Zech 7:10)

אֲשֶׁר חָשְׁבוּ רָעוֹת בְּלֵב

…who devised [חָשְׁבוּ] evil [things] in the heart [בְּלֵב]…. (Ps. 140:3)

οἵτινες ἐλογίσαντο ἀδικίας ἐν καρδίᾳ

…whoever considered [ἐλογίσαντο] wicked [things] in the heart [ἐν καρδίᾳ]…. (Ps. 139:3)

Bovon thought the author of Luke had a favorable view of the people’s speculations about John the Baptist’s messianic status,[21] but the considerable trouble the author of Luke appears to have taken to tone down their expectations suggests otherwise.

If Luke 3:15 is ultimately derived from a Hebrew source that read וַיַּחְשְׁבוּ…בְּלִבָּם (“and they considered…in their heart”), then, given the negative contexts in which חָשַׁב בְּלֵב occurs in the examples cited above,[22] it is probable that the Hebrew source behind Anth. regarded the people’s speculations in a decidedly unfavorable light.

בְּלִבָּם (HR). In LXX ἐν [ταῖς] καρδίαις αὐτῶν (en [tais] kardiais avtōn, “in their hearts”) occurs about as often as the translation of בִּלְבָבָם (bilvāvām, “in their heart”)[23] as of בְּלִבָּם (belibām, “in their heart”).[24] We have preferred the latter form for HR because whereas we find examples of בְּלִבָּם in tannaic sources (cf., e.g., m. Mid. 2:2; t. Sanh. 14:3), examples of בִּלְבָבָם occur only in biblical quotations. On reconstructing καρδία (kardia, “heart”) with לֵב (lēv, “heart”), see Four Soils interpretation, Comment to L32.

L4 Ἰωάννης (GR). We suspect that περὶ τοῦ Ἰωάνου (peri tou Iōanou, “concerning John”) reflects the author of Luke’s more delicate handling of the crowds’ speculations. In contrast to his roundabout wording, Luke’s source (Anth.) may simply have quoted the crowds as saying, “John: he’s the Messiah!”

יוֹחָנָן (HR). On reconstructing the name Ἰωάννης (Iōannēs, “John”) as יוֹחָנָן (yōḥānān, “John”), see Choosing the Twelve, Comment to L25.

L5 αὐτὸς ὁ χριστός ἐστιν (GR). Luke’s Greek in L5 is difficult to reconstruct in Hebrew, and the hesitant language he used (“Perhaps he might be the Messiah”) may be a reflection of his own discomfort with the sentiment the crowds expressed in his source. A statement such as αὐτὸς ὁ χριστός ἐστιν (avtos ho christos estin, “He is the Messiah”), which reverts neatly to Hebrew, could easily have been modified into Luke’s μήποτε αὐτὸς εἴη ὁ χριστός (mēpote avtos eiē ho christos, “Perhaps he might be the Messiah”).

הוּא הַמָּשִׁיחַ (HR). In LXX the adjective χριστός (christos, “anointed”) usually occurs as the translation of מָשִׁיחַ (māshiaḥ, “anointed”).[25] Likewise, most instances of מָשִׁיחַ in MT were translated χριστός in LXX.[26] The Fourth Gospel, too, equates μεσσίας (messias, “Messiah”), a hellenized form of מָשִׁיחַ, with χριστός (John 4:25).

In the Second Temple period there was no single concept of “the Messiah” as Christians think of it today. “The anointed one” might be an eschatological high priest, appointed to purify the Temple and properly institute the divine service according to the “correct” interpretation of the Torah. Or “the anointed one” might be an eschatological warrior-king who would restore the royal household of David and vanquish Israel’s foes. Some Second-Temple Jewish thinkers had a place for both a messianic priest and a messianic king in their eschatological schemes, while for others all that was important was that Israel be redeemed, no matter who accomplished it. Since John the Baptist was a priest by birth, if the crowds entertained speculations about his messianic status, then surely they envisioned him as a candidate for the eschatological high priest.[27]

L6 καὶ ἀπεκρίνατο Ἰωάννης (GR). Luke 3:16 does not open with a coordinating conjunction such as καί (kai, “and”) or δέ (de, “but”), but we would have expected Anth. to have some such equivalent for the vav attached to a vav-consecutive verb. Perhaps the author of Luke dropped the conjunction in his revision of Anth.’s wording. Our decision to prefer καί over δέ for GR has been guided by the parallel in Mark, which opens with καί and may reflect the wording of Anth.

Mark’s use of the verb κηρύσσειν (kērūssein, “to proclaim”) in L6 (Mark 1:7) harks back to the description of John the Baptist’s proclaiming (κηρύσσων) an immersion of repentance for the release of sins in A Voice Crying, L34 (Mark 1:4; Luke 3:3). Since κηρύσσειν is not an appropriate verb for a response, Luke’s verb, ἀποκρίνειν (apokrinein, “to answer”), is more likely to reflect the wording of Anth.

Whether or not the form ἀπεκρίνατο (apekrinato, “he answered”)—a middle rather than the more usual passive form (viz., ἀπεκρίθη [apekrithē, “he answered”])—stood in Anth. is exceedingly difficult to decide. In LXX ἀπεκρίνατο occurs only 4xx (Exod. 19:19; Judg. 5:29; 1 Chr. 10:13; Ezek. 9:11), and in NT only 7xx (Matt. 27:12; Mark 14:61; Luke 3:16; 23:9; John 5:17, 19; Acts 3:12), so one might conclude from its rarity that its presence in Luke 3:15 is redactional. But by the same token we are forced to admit that the use of ἀπεκρίνατο is not typical of Lukan redactional style.[28] Perhaps, therefore, the author of Luke used the less usual form ἀπεκρίνατο because it appeared in his source. Neither form is more Hebraic than the other, as both forms can be reverted to Hebrew as עָנָה (‘ānāh, “answer”), so the criterion of ease of reconstruction cannot help us reach a decision. In the end, we preferred to retain ἀπεκρίνατο for GR on the basis of Luke’s generally conservative approach to his sources. Even when revising his source, he tended not to change any more of its original wording than necessary. Since the use of ἀπεκρίνατο instead of ἀπεκρίθη is not an improvement of Greek style, the author of Luke likely used the form ἀπεκρίνατο because he copied it from Anth.

Finally, for GR we have moved John’s name up from L8 to a more Hebraic position.

וַיַּעַן יוֹחָנָן אוֹתָם (HR). On reconstructing ἀποκρίνειν (apokrinein, “to answer”) with עָנָה (‘ānāh, “answer”), see Call of Levi, Comment to L56.

On reconstructing Ἰωάννης (Iōannēs, “John”) with יוֹחָנָן (yōḥānān, “John”), see above, Comment to L4.

We have added אוֹתָם (’ōtām, “them”) to HR based on our observation that in MT, when עָנָה is followed by לֵאמֹר, as in our reconstruction, לֵאמֹר is often preceded by the direct object marker:

וַיַּעֲנוּ בְנֵי חֵת אֶת־אַבְרָהָם לֵאמֹר לוֹ

And the sons of Het answered Abraham, saying to him…. (Gen. 23:5)

וַיַּעַן עֶפְרוֹן אֶת־אַבְרָהָם לֵאמֹר לוֹ

And Ephron answered Abraham, saying to him…. (Gen. 23:14)

וַיַּעַן יוֹסֵף אֶת־פַּרְעֹה לֵאמֹר

And Joseph answered Pharaoh, saying…. (Gen. 41:16)

וַיַּעַן רְאוּבֵן אֹתָם לֵאמֹר

And Reuben answered them, saying…. (Gen. 42:22)

וַיַּעֲנוּ אֶת־יְהוֹשֻׁעַ לֵאמֹר

And they answered Joshua, saying…. (Josh. 1:16)

L7 לֵאמֹר (HR). On reconstructing a participial form of λέγειν (legein, “to say”) with the infinitive construct לֵאמֹר (lē’mor, “to say”), see Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L5-6.

L8 πᾶσιν ὁ Ἰωάνης (Luke 3:16). The reiteration of πᾶς (pas, “all”; cf. L2), the addition of the definite article to John’s name,[29] and the un-Hebraic word order are all probably due to Lukan redaction. We have therefore omitted L8 from GR. Just as the author of Luke was intent upon weakening the confident assertion that John the Baptist was the Messiah, so he endeavored to reinforce the Baptist’s denial to everyone of his messianic role.

L9 ἐγὼ μὲν βαπτίζω ὑμᾶς ὕδατι (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreements against Mark confirm that their order—mentioning the medium of John’s immersion before his prophecy of Someone coming after him—is that of Anth. The author of Mark was far more interested in the Baptist’s prophecy, which he believed concerned Jesus, than he was about the rest of John’s message, which, for the most part, he omitted.

The Lukan-Matthean minor agreements also confirm that μέν (men, “on the one hand”) and the present tense βαπτίζω (baptizō, “I am immersing”) belonged to Anth.

Nevertheless, questions of word order remain. Luke placed the medium of immersion, ὕδατι (hūdati, “with water”), ahead of the verb and the object. His word order is un-Hebraic[30] and appears to have been motivated by a desire to emphasize the contrast between John’s water immersion and the spirit-and-fire immersion of the coming Someone.[31] We have therefore preferred to place the medium in its Hebraic position at the end of the clause, as indicated by Mark and Matthew.

Another word-order decision we face in L9 is where to place ὑμᾶς (hūmas, “you”), the object of John’s immersions. The position of ὑμᾶς after the verb in Luke and Mark is more Hebraic than its position in Matthew,[32] but in L22 Luke and Matthew agree to write ὑμᾶς βαπτίσει (hūmas baptisei, “you he will immerse”) against Mark’s βαπτίσει ὑμᾶς (baptisei hūmas, “he will immerse you”), which strongly suggests that, at least in L22, and therefore possibly also in L9, Anth. had the order object→verb.

We are thus faced with a question of probability. Did the author of Luke move ὑμᾶς from its position in Anth., thereby accidentally achieving a more Hebraic word order, which was subsequently followed by Mark? Or did the author of Matthew move ὑμᾶς from its position in Anth. so that ὑμᾶς would appear in the same position in both L9 and L22 (i.e., before the verb)? Since it is difficult to understand why the author of Luke would have made such an arbitrary change to Anth.’s word order, while the explanation that Matthew made the change in order to produce better symmetry between the two parts of the Baptist’s saying is a reasonable conjecture,[33] we have accepted the Lukan-Markan placement of ὑμᾶς for GR.[34]

John the Baptist as depicted in a mosaic at the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Finally, with respect to GR in L9, there is the question of whether the ἐν (en, “in”) that the author of Matthew affixed to ὕδατι is a reflection of Anth. or whether he added the preposition to create symmetry with L23, which includes ἐν. Certainly the inclusion of ἐν is more Hebraic, since it corresponds to [no_word_wrap]-בְּ[/no_word_wrap], which is necessary in HR, but in this case the probability of accidentally adopting a more Hebraic reading seems evenly balanced with the likelihood that the author of Matthew added ἐν for the sake of symmetry.[35] Jesus’ allusion to John’s saying in Acts 1:5 (cf. Acts 11:16) omits the ἐν before ὕδατι, but since we believe that Jesus’ prophecy of immersion in the Holy Spirit influenced the wording of the synoptic versions of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse (see below, Comment to L23), appealing to Acts 1:5 is less than decisive. In the end, we have decided to omit ἐν from GR. Having caught the author of Matthew in the act of creating symmetry once in L9, it is reasonable to attribute the presence of ἐν to the same cause.

אֲנִי מַטְבִּיל אֶתְכֶם בַּמַּיִם (HR). In LXX βαπτίζειν (baptizein, “to immerse”) occurs as the translation of טָבַל (ṭāval, “immerse”) in the story of Naaman’s immersing himself in the Jordan (4 Kgdms. 5:14). In MH the transitive sense (i.e., the immersion of objects and overseeing the immersion of other persons) was typically expressed with the root [no_word_wrap]ט-ב-ל[/no_word_wrap] in the hif‘il stem.[36] Since overseeing immersions was precisely what earned John the Baptist his title, reconstructing with the hif‘il participle מַטְבִּיל (maṭbil, “immersing”) is the optimal choice for HR.[37]

In LXX, where ὕδωρ (hūdōr, “water”) occurs frequently, it nearly always translates מַיִם (mayim, “water”) in the underlying Hebrew text.[38] Despite a surprising variety of renderings, the overwhelming majority of instances of מַיִם in MT were rendered ὕδωρ in LXX.[39] We have reconstructed the anarthrous ὕδατι (“in/with water”) with the definite בַּמַּיִם (bamayim, “in the water”) in accordance with Hebrew preference. Several times in LXX בַּמַּיִם was translated with the indefinite phrase [ἐν] ὕδατι ([en] hūdati, “in water”; cf., e.g., Exod. 12:9; 29:4; 40:12; Lev. 1:9, 13; 6:21; 8:6, 21; 14:8, 9; 15:5).

John’s medium for immersion—water—may offer a clue as to the Baptist’s self-understanding. Whereas others may have speculated that John was Elijah returned (cf. John 1:21),[40] John likely saw his role as preparing the way for Elijah’s coming.[41] According to one interpretation of the prophecies of Malachi, Elijah would return to the Temple (Mal. 3:1) to deal with an erring priesthood.[42] Elijah would come in fiery awesomeness (Mal. 3:2) to refine the sons of Levi, bring judgment upon evildoers (Mal. 3:5), and reinstitute the divine service according to the Torah’s precepts (Mal. 3:4).[43] If one were to ask when this purification of the priesthood and reinstitution of the proper rites of the divine service would take place, a likely answer would be the Day of Atonement, since on this day the Temple underwent an annual purification from the impurity of sin.

This picture of Elijah’s eschatological return accords well with John’s baptism of repentance for the release of (the debt of) sins, which seems to be based on a Sabbatical or Jubilee Year proclamation of amnesty that would become effective on the eschatological Day of Atonement (see A Voice Crying, Comment to L36).

Elijah slays the priests of Baal. Statue on the summit of Mount Carmel. Photograph courtesy of Joshua N. Tilton.

Especially in view of his prophecy of Someone who would purify the threshing floor—likely a cipher for the Temple (see below, Comment to L28)—it appears that John’s immersions in water were a preparation for the fiery purification of the Temple and the priesthood (and evidently the rest of Israel as well), which Elijah would administer when he returned. As Robinson noted, water was not a medium in which Elijah operated: “As on Carmel, Elijah was the one to appear on the scene when Israel (symbolized deliberately in the twelve stones out of which the altar was made) had already been drenched with water: then he [i.e., Elijah—DNB and JNT] would come near and call down fire from the Lord (I Kings 18.30-9).”[44] In other words, just as lowly servants had doused the twelve stones representing Israel ahead of Elijah’s fiery vindication of the true form of worship, so John the Baptist was a lowly servant, immersing Israel in water ahead of its fiery ordeal at the hands of the same incendiary prophet.[45] The water immersions John administered were the only means by which Israel would survive Elijah’s imminent fiery judgment.

L10 εἰς μετάνοιαν (Matt. 3:11). We agree with those scholars who regard “for repentance” as a Matthean addition.[46] Harnack argued that it is difficult to imagine the author of Matthew adding “for repentance” on his own initiative, since he only used the term μετάνοια (metanoia, “repentance”) on one other occasion (Matt. 3:8), and then only because it occurred in his source, as proven by the parallel in Luke 3:8.[47] Catchpole, on the other hand, argued that it is even more difficult to imagine the author of Luke rejecting εἰς μετάνοιαν had it occurred in his source, since he used this very phrase elsewhere in his Gospel (Luke 5:32), and the noun μετάνοια occurs with much greater frequency in Luke (5xx) compared to Mark (1x) and Matthew (2xx), indicating that repentance was a subject dear to the author of Luke’s heart.[48]

We suspect that the addition of εἰς μετάνοιαν (eis metanoian, “for repentance”) in L10 is symptomatic of the author of Matthew’s aversion to the notion that John’s immersions were εἰς ἄφεσιν ἁμαρτιῶν (eis afesin hamartiōn, “for the release of sins”; Mark 1:4 // Luke 3:3).[49] For the author of Matthew, only Jesus’ blood was effective εἰς ἄφεσιν ἁμαρτιῶν (“for the release of sins”; Matt. 26:28).

L11 ὁ δὲ ὀπίσω μου ἐρχόμενος (Matt. 3:11). Matthew’s word order in L11 is un-Hebraic,[50] and it appears as though the author of Matthew attempted to reformulate “the One mightier than I is coming behind me” into a title (“the One Coming Behind Me”) in anticipation of John the Baptist’s question, “Are you the Coming One?” (Matt. 11:3; Luke 7:19, 20).[51] It is unlikely, therefore, that Matthew’s wording is identical to Anth.’s.[52]

ἔρχεται δὲ (GR). Since Luke and Matthew agree against Mark to utilize a μέν…δέ (men…de, “on the one hand…on the other hand”) construction in L9-11, there can be little doubt that this construction was found in Anth. We have accordingly accepted Luke’s δέ (de, “but”) in L11 for GR.

וַהֲרֵי בָּא (HR). Reconstructing ἔρχεται δέ (erchetai de, “but is coming”) as וּבָא (ūvā’, “and is coming”) might be more straightforward,[53] but [no_word_wrap]-וְ[/no_word_wrap] (ve–, “and”) hardly expresses the dramatic contrast that John implied existed between himself and the coming Someone. Sometimes the LXX translators rendered וְהִנֵּה (vehinēh) simply with the conjunction καί (“and”) or δέ (“but”) without any equivalent corresponding to הִנֵּה (“behold”), as we see in the following examples:

וְהִנֵּה יי נִצָּב עָלָיו

And behold [וְהִנֵּה]! The LORD stood above it…. (Gen. 28:13)

ὁ δὲ κύριος ἐπεστήρικτο ἐπ᾿ αὐτῆς

And [δὲ] the Lord leaned on it…. (Gen. 28:13; NETS)

וְהִנֵּה שֶׁבַע פָּרוֹת אֲחֵרוֹת עֹלוֹת אַחֲרֵיהֶן מִן הַיְאֹר

And behold [וְהִנֵּה]! Seven other cows are coming up after them from the Nile…. (Gen. 41:3)

ἄλλαι δὲ ἑπτὰ βόες ἀνέβαινον μετὰ ταύτας ἐκ τοῦ ποταμοῦ

But [δὲ] seven other cows were coming up after these from the river…. (Gen. 41:3)

וְהִנֵּה שֶׁבַע שִׁבֳּלִים דַּקּוֹת וּשְׁדוּפֹת קָדִים צֹמְחוֹת אַחֲרֵיהֶן

And behold [וְהִנֵּה]! Seven heads of grain, scrawny and scorched by the east wind, are growing up after them. (Gen. 41:6)

ἄλλοι δὲ ἑπτὰ στάχυες λεπτοὶ καὶ ἀνεμόφθοροι ἀνεφύοντο μετ᾿ αὐτούς

But [δὲ] seven other heads of grain, scrawny and wind-blasted, were growing up after them. (Gen. 41:6)

וְהִנֵּה מִצְרַיִם נֹסֵעַ אַחֲרֵיהֶם

And behold [וְהִנֵּה]! Egyptians are marching behind them! (Exod. 14:10)

καὶ οἱ Αἰγύπτιοι ἐστρατοπέδευσαν ὀπίσω αὐτῶν

…and [καὶ] the Egyptians encamped behind them…. (Exod. 14:10; NETS)

וְהִנֵּה שְׁמוּאֵל בָּא

And behold [וְהִנֵּה]! Samuel is coming! (1 Sam. 13:10)

καὶ Σαμουηλ παραγίνεται

…and [καὶ] Samuel comes along…. (1 Kgdms. 13:10)

Lindsey noted that ἰδοῦ (idou, “behold”) does occur in the form of the Baptist’s saying quoted in Acts 13:25 (see above, Conjectured Stages of Transmission).[54] The interjection ἰδοῦ cannot have occurred in Anth., since there is no place for it to fit within the μέν…δέ construction, but perhaps the version in Acts 13:25 reflects an independent witness to the Hebrew version of John’s saying.[55]

Instead of הִנֵּה we have adopted הֲרֵי (harē, “behold”), which in MH took the place of הִנֵּה. Since L11 reflects direct speech, it seems more natural to use הֲרֵי in our reconstruction than the archaic-sounding הִנֵּה.

L12 ὁ ἰσχυρότερός μου (Luke 3:16). The possibility that Acts 13:25 preserves an independent witness to the Hebrew version of John the Baptist’s saying opened our eyes to the fact that an equivalent to ἰσχυρότερός μου (ischūroteros mou, “mightier than I”) is conspicuously absent from the Acts version of the Baptist’s saying. “Mightier than I” is absent in the Johannine version as well (see above, Conjectured Stages of Transmission). Conversely, something corresponding to “after me” is present in the Acts version of the Baptist’s saying (Acts 13:25; cf. Acts 19:4), but absent in Luke 3:16. Perhaps, therefore, ἰσχυρότερός μου (“mightier than I”) is simply the author of Luke’s substitute for Anth.’s ὀπίσω μου (opisō mou, “after me”). The author of Luke may have disliked the connotation of ἔρχεται ὀπίσω μου (“he is coming behind me”),[56] since elsewhere in his Gospel ἔρχεσθαι ὀπίσω μου (“to come behind me”) is synonymous with “to be my [i.e., Jesus’] disciple” (Luke 9:23; 14:27).[57] Replacing “after me” with “mightier than I” enabled the author of Luke to avoid suggesting that Jesus was John’s disciple and to more accurately (in his view) describe the relationship between John the Baptist and Jesus.

L13 ὀπίσω μου (GR). If we are correct in supposing that “mightier than I” is Luke’s substitute for “after me,” then it appears that the author of Mark simply combined the two phrases he saw in his sources: ἰσχυρότερός μου from Luke and ὀπίσω μου from Anth. The author of Matthew inherited the combination from Mark, but rearranged the wording in order to speak of a Coming One instead of a Mightier One.

As we noted in Comment to L12, the Acts version of John the Baptist’s saying, which occurs in a speech delivered by Paul, has something corresponding to “after me,” namely μετ᾿ ἐμὲ (met eme, “after me”; Acts 13:25). Another Pauline speech in Acts alludes to John the Baptist’s saying, and it, too, includes something corresponding to “after me”:

Ἰωάννης ἐβάπτισεν βάπτισμα μετανοίας τῷ λαῷ λέγων εἰς τὸν ἐρχόμενον μετ᾿ αὐτὸν ἵνα πιστεύσωσιν, τοῦτ᾿ ἔστιν εἰς τὸν Ἰησοῦν

John immersed with an immersion of repentance, speaking to the people that they might believe in the one coming after him [μετ᾿ αὐτὸν], namely in Jesus. (Acts 19:4)

The Johannine version of the Baptist’s saying, like Mark and Matthew, has ὀπίσω μου (John 1:27).

אַחֲרַי (HR). On reconstructing ὀπίσω μου (opisō mou, “after me”) with אַחֲרַי (’aḥarai, “after me”), see Demands of Discipleship, Comment to L24-25.

L14 ἐστιν (Matt. 3:11). The presence of the verb εἶναι (einai, “to be”) in L14 is due to the author of Matthew’s transformation of Mark’s “the One Mightier Than I is coming after me” into “the One Coming After Me is mightier than I” (see above, Comment to L11).

A first-century C.E. sandal discovered in the Northern Palace at Masada. Photographed at the Israel Museum by Joshua N. Tilton.

L15 οὗ οὐκ εἰμὶ ἱκανὸς (GR). All three synoptic versions of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse, as well as the Acts and Johannine versions of the Baptist’s saying, include the notice about John’s unworthiness to perform menial tasks for the Someone whose coming he announces. There can be little doubt, therefore, that John’s unworthiness belonged to the original form of the saying, and since all three synoptic writers are agreed on the wording, we have accepted their testimony for GR.

מִי שֶׁאֵינִי כָּשֵׁר (HR). Elsewhere in LOY we have used [no_word_wrap]-מִי שֶׁ[/no_word_wrap] (mi she-, “one that”) to reconstruct ὅς ἐάν (hos ean, “whoever”)[58] and ὅστις (hostis, “whoever”),[59] but [no_word_wrap]-מִי שֶׁ[/no_word_wrap] is also suitable for reconstructing ὅς (hos, “who,” “that”).

More difficult is determining how to reconstruct “I am not sufficient,” since Hebrew has various words meaning “qualified,” “worthy,” “suitable” that might serve as an equivalent to ἱκανός (hikanos). One option we considered for HR is כְּדַי (kedai, “fitting,” “deserving”), but the one time we encounter the statement אֵינִי כְּדַי in rabbinic sources the speaker protests that a certain situation is beneath his dignity, not that he is unworthy.[60]

Another option is, רָאוּי (rā’ūy, “worthy,” “qualified”). Example of אֵינִי רָאוּי with a meaning more or less equivalent to “I am not worthy” are found in the following denials:

תנו רבנן אל יאמר אדם תלמיד אני איני ראוי להיות יחיד

Our rabbis taught [in a baraita]: Let not a person say, “I am only a disciple, I am not worthy [אֵינִי רָאוּי] to be a yaḥid [i.e., someone who distinguishes himself from the crowd by performing extraordinary acts of piety—DNB and JNT].” (b. Taan. 10b)

However, elsewhere in LOY we have used רָאוּי to reconstruct ἄξιος (axios, “worthy”).[61] It therefore seems preferable to use a different term to reconstruct ἱκανός (hikanos, “sufficient”). We have therefore settled on כָּשֵׁר (kāshēr, “fit,” “qualified”), a term that is especially used in ritual contexts, such as qualification for the priesthood or as offerings for the altar, as in the following examples:

אינו כשר לא לכהן גדול ולא לכהן הדיוט

He is not ritually fit [אֵינוֹ כָּשֵׁר] either to be high priest or to be an ordinary priest. (t. Yom. 1:4; Vienna MS)

בעל מום שאינו כשר לגבי מזבח

A sacrificial animal with a physical blemish that is not fit [שֶׁאֵינוֹ כָּשֵׁר] for the altar…. (Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Pisḥa §18 [ed. Lauterbach, 1:108)

On the lips of John the Baptist the priest in his discourse on the eschatological purification of the Temple the adjective כָּשֵׁר seems entirely appropriate. On reconstructing ἱκανός with כָּשֵׁר, see Centurion’s Slave, Comment to L31.

L16 κύψας (Mark 1:7). Mark’s is the only version of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse to include the image of the Baptist’s bending down in order to tend to the shoes of the one whose coming he announces. Neither is there an equivalent to “bending” in the Acts or Johannine versions of the Baptist’s saying. It seems likely, therefore, that “bending down” is simply a colorful flourish added by the author of Mark.[62]

L17 λῦσαι (GR). Every version of the Baptist’s saying except Matthew’s uses the verb λύειν (lūein, “to loosen”) to describe the action John accounted himself unworthy to perform. With such strong attestation from multiple sources, it seems unavoidable that we should accept Luke’s and Mark’s wording for GR.[63]

לְהַתִּיר לוֹ (HR). The verb λύειν (lūein, “to loosen”) is not all that common in LXX,[64] but it twice occurs in relation to the noun ὑπόδημα (hūpodēma, “shoe”; Exod. 3:5; Josh. 5:15), the very term for “shoe” that occurs in Luke and Mark at L19. In those two verses λύειν serves as the translation of נָשַׁל (nāshal, “remove”), which is an action different from the one John the Baptist describes. Fortunately, there are several places in rabbinic sources that describe the untying of shoes, which can serve as models for our reconstruction:

נעל לו מנעלו והתיר לו מנעלו

…he ties his shoe for him and he unties his shoe for him. (y. Kid. 1:3 [12a])

התיר רצועות מנעל וסנדל

He untied the straps of his shoe and sandal. (b. Shab. 112a)

אמר רבי יהושע בן לוי כל מלאכות שהעבד עושה לרבו תלמיד עושה לרבו חוץ מהתרת (לו) מנעל

Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said, “All the duties that a slave performs for his master, a disciple performs for his master, except for untying his shoe for him.” (b. Ket. 96a)

התיר לו מנעלו

…he untied his shoe for him…. (b. Kid. 22b)

נעל לו מנעלו או התיר לו מנעלו

…he tied his shoe for him, or he untied his shoe for him…. (b. Bab. Bat. 53b)

התיר מנעליו ויצא לשוק הרי זה מגסי הרוח

If he untied his shoes and went to the market, behold, this one is haughty of spirit. (Tosefta Derech Eretz 6:15 [ed. Higger, 316])

The above sources demonstrate that הִתִּיר (hitir, “release,” “untie”) is the Hebrew verb used to describe the untying of shoes. The above sources also support our inclusion of לוֹ (lō, “for him”) in HR despite the lack of anything corresponding to the preposition with pronominal suffix in the Greek text. In Hebrew [no_word_wrap]-לְ + [/no_word_wrap] suffix appears to have been necessary when referring to the untying of someone else’s shoes. In Greek, however, translating לוֹ would have been superfluous.

In LXX λύειν (“to loosen”) occurs as the translation of הִתִּיר (“release,” “untie”) in Ps. 104[105]:20; 145[146]:7.

L18 רְצוּעַת (HR). In one of the sources cited in the previous comment (b. Shab. 112a) we saw that the Hebrew noun for “shoe strap” is רְצוּעָה (retzū‘āh). This term does not occur in the Hebrew Bible or in the Dead Sea Scrolls. References to shoe straps (רְצוּעוֹת מִנְעָל; m. Shab. 15:2; m. Neg. 11:11) and sandal straps (רְצוּעוֹת סַנְדַּלִּים; m. Kel. 26:9), however, do occur in the Mishnah.

First-century ivory sandaled foot. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

L19 מִנְעָלָיו (HR). On reconstructing ὑπόδημα (hūpodēma, “shoe,” “sandal”) with מִנְעָל (min‘āl, “shoe,” “sandal”), see Conduct on the Road, Comment to L73.

L20 βαστάσαι (Matt. 3:11). Why the author of Matthew decided to change the imagery from untying shoes to carrying them is anyone’s guess.[65]

L21 ἐγὼ ἐβάπτισα ὑμᾶς ὕδατι (Mark 1:8). Scholarly opinion is divided between those who regard Mark’s aorist ἐβάπτισα (ebaptisa, “I immersed”) as a Semitism, and upon that basis argue that Mark’s aorist should be understood as having present force (i.e., “I immerse”),[66] and those who think that Mark’s aorist is theologically motivated in order to make John himself confess that his immersions are over and done with.[67] The weakness of the first suggestion is that it is very difficult to imagine a context in which the statement אֲנִי הִטְבַּלְתִּי אֶתְכֶם בַּמַּיִם would not convey its usual sense of “I used to immerse you in water.” The second suggestion might be correct. Another possibility is that the author of Mark picked up the aorist verb from Acts 1:5 (cf. Acts 11:16).

L22 αὐτὸς ὑμᾶς βαπτίσει (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreement to omit δέ (de, “but”) from L22 confirms that it did not occur here in Anth. Mark’s δέ in L22 makes up for the δέ the author of Mark omitted in L11.

הוּא יַטְבִּיל אֶתְכֶם (HR). On reconstructing βαπτίζειν (baptizein, “to immerse”) with הִטְבִּיל (hiṭbil, “immerse”), see above, Comment to L9.

L23 ἐν πνεύματι (GR). Despite its absence in Codex Vaticanus, it is likely that the original text of Mark, like that of Luke and Matthew, also included the preposition ἐν (en, “in”), as the critical editions indicate. The preposition ἐν also occurs in Jesus’ allusion to John’s saying in Acts 1:5 (cf. Acts 11:16). Given the strong attestation of ἐν, we see no reason not to include it in GR.

On the other hand, although the adjective ἁγίῳ (hagiō, “holy”) is just as strongly attested, we have reason to believe it did not come from Anth. Immersion in the Holy Spirit is surprising in the context of John the Baptist’s warnings of a coming judgment, and it does not agree with the imagery of the threshing floor, which the Baptist used to illustrate the impending immersion in the Lukan and Matthean versions of Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse. Several scholars have suggested that instead of speaking of an immersion in the Holy Spirit and fire (ἐν πνεύματι ἁγίῳ καὶ πυρί), the Baptist originally warned of an immersion in wind and fire (ἐν πνεύματι καὶ πυρί).[68] This suggestion fits with the Baptist’s message: Someone is coming to bring a swift and terrible judgment on the wicked, but now, in this moment, God is offering you a final opportunity for clemency. Be immersed in the Jordan and bear the fruits of repentance—that is the only way you will survive the coming immersion that will destroy everything but the wheat. The eschatological Day of Atonement is coming, so avail yourselves now of his Jubilee release from the indebtedness of sin, lest when He Who Is Coming arrives to purify the Temple,[69] he discovers that you, too, are defiled with the impurity of sin.

Outpouring of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost as depicted in a thirteenth-century Nestorian Peshitta Gospel. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Not only does immersion in wind and fire make sense in the context of the Baptist’s message, it is easy to see how his prophecy was transformed into predicting an immersion in the Holy Spirit and fire. According to Acts 1:5, when Jesus promised the pouring out of the Holy Spirit he said, “John immersed in water, but in a few days you will be immersed in a holy spirit.” In this way Jesus put a new twist on John’s prophecy consistent with Jesus’ dissent from John regarding the timing of the final judgment. Whereas John believed that Israel was teetering on the edge of the end of history, Jesus believed that between the former age and the eschaton there would be an historical period during which the Kingdom of Heaven would redeem Israel and restore creation. Only after the period of the Kingdom of Heaven was completed would the final judgment come.[70]

In contrast to John’s prediction of an imminent immersion of judgment in wind and fire, Jesus promised an immersion of creative renewal in the Holy Spirit. The way he put a new twist on John’s saying was simple and elegant: John’s ἐν πνεύματι καὶ πυρί = בָּרוּחַ וּבָאֵשׁ (bārūaḥ ūvā’ēsh, “in the wind and in the fire”) became ἐν πνεύματι ἁγίῳ = בְּרוּחַ הַקֹּדֶשׁ (berūaḥ haqodesh, “in the Holy Spirit”).

The author of Luke, who was well acquainted with Jesus’ promise of the Holy Spirit, was probably unaware of the clever wordplay Jesus had invented to transform the meaning of the Baptist’s prophecy. Therefore, when he read the words of John’s prophecy as they appeared in Anth., he interpreted them through the lens of Jesus’ promise, wrongly taking ἐν πνεύματι καὶ πυρί to mean “in Spirit and fire” instead of “in wind and fire” as the Baptist intended. Probably the author of Luke thought that ἐν πνεύματι (as he assumed, “in Spirit”) was too obscure for his readers, so he added ἁγίῳ (hagiō, “holy”), which he knew from Jesus’ saying.

The author of Mark not only accepted “Holy Spirit” from Luke, he also dropped “fire,” since his familiarity with Acts 1:5 convinced him that John’s prediction could only concern the giving of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost.[71] The author of Matthew, as was so often his practice, simply combined Mark’s wording with Anth.’s, undoubtedly assuming that Mark’s “Holy Spirit” was the correct interpretation of Anth.’s ἐν πνεύματι.[72]

Supposing the Baptist originally described an immersion in wind and fire is preferable to the following alternative suggestions:

- The Baptist originally spoke only of immersion in the Holy Spirit, as reflected in Mark, and fire was added to the tradition behind the versions in Luke and Matthew.[73]

- The Baptist originally spoke only of immersion in fire, which the author of Mark replaced with “Holy Spirit,” and the two versions (Holy Spirit and fire) were combined either in the tradition behind the Lukan and Matthean versions, or by the authors of Luke and Matthew independently.[74]

- The Baptist spoke all along of two immersions: one in the Holy Spirit for the salvation of those who repented, and one in fire for the destruction of the unrepentant.[75]

None of these alternate solutions can account for the specific imagery of the threshing floor, which the Baptist used to elucidate the meaning of the coming immersion. An immersion in wind and fire, on the other hand, naturally leads into the imagery of the threshing floor, since wind blows away chaff, fire burns stubble, and only wheat remains to be gathered into the storehouse.

Support for the hypothesis that John the Baptist originally spoke of an immersion in wind and fire can be found, of all places, in Luke’s account of the giving of the Holy Spirit in Acts. This account, which is the fulfillment of Jesus’ promise in Acts 1:5 (“John immersed in water, but in a few days you will be immersed in a holy spirit”), contains two details that become immediately explicable against the background of the Baptist’s prophecy of an immersion in wind and fire:

- a sound “like rushing wind” (ὥσπερ φερομένης πνοῆς) that filled the house (Acts 2:2)

- tongues “like fire” (ὡσεὶ πυρός) that rested on the apostles (Acts 2:3)

The significance of these odd details is never explained in Acts, which suggests that the author of Luke inherited them from his source.[76] That source was evidently at pains to demonstrate that John’s prophecy of an immersion in wind and fire was fulfilled at Pentecost. The author of Luke, on the other hand, displays no awareness of tension between John’s prophecy and Jesus’ promise. As his addition of ἁγίῳ (“holy”) to L23 shows, the author of Luke believed the Baptist had spoken of an immersion in the Holy Spirit all along.

Furthermore, immersion in wind and fire accords well with the identification of the Someone whose coming John the Baptist foretold as Elijah, since wind and fire feature prominently in two key events during Elijah’s career. First, on Mount Horeb a great wind (רוּחַ גְּדוֹלָה), an earthquake and fire (אֵשׁ) preceded the voice of the LORD (1 Kgs. 19:11-12). Second, when Elijah was translated to heaven, a chariot of fire (רֶכֶב אֵשׁ) and horses of fire (סוּסֵי אֵשׁ) appeared and he was taken up in a whirlwind (סְעָרָה; 2 Kgs. 2:11). Thus, Elijah was strongly associated with both wind and fire in the biblical tradition, so it is fitting that these should be the media in which his immersion should be conducted.[77]

With the understanding that John the Baptist spoke of an immersion in wind and fire, a clearer insight is gained into the Baptist’s high self-awareness. Notwithstanding his protestation of being unworthy to untie the shoe straps of the one who was coming, one’s response to John’s proclamation of a baptism of repentance for the release of sins would determine whether or not the immersion administered by the coming one would result in destruction.[78] When the threshing floor was engulfed in wind and fire, only the wheat—which is to say, those who had received John’s watery ablution—would be spared.[79]

בָּרוּחַ (HR). On reconstructing πνεῦμα (pnevma, “wind,” “spirit”) with רוּחַ (rūaḥ, “wind,” “spirit”), see Return of the Twelve, Comment to L25. Just as we reconstructed the anarthrous ὕδατι (“in/with water”) with the definite בַּמַּיִם (“in the water”) in L9, so in L23 we have reconstructed ἐν πνεύματι (“in wind”) with בָּרוּחַ (“in the wind”) for the same reasons.

L24 καὶ πυρί (GR). The Lukan-Matthean agreement against Mark to include “and fire” demonstrates that this phrase was derived by both authors from Anth.

וּבָאֵשׁ (HR). On reconstructing πῦρ (pūr, “fire”) with אֵשׁ (’ēsh, “fire”), see Darnel Among the Wheat, Comment to L32. In MT the phrase וּבָאֵשׁ (ūvā’ēsh, “and in the fire”) occurs twice; in both instances the LXX translators rendered it without the definite article as καὶ ἐν πυρί (kai en pūri, “and in fire”; 2 Kgdms. 23:7; Zeph. 1:18).[80]

L25-32 The high level of verbal agreement in L25-32 indicates that the authors of Matthew and Luke copied the Purifying the Threshing Floor saying from Anth.[81] Since GR attempts to reconstruct the wording of Anth., which is never in doubt in DT when Luke and Matthew are in agreement, there will be no need for further comment on GR except when Luke and Matthew disagree.

The agreement of the authors of Luke and Matthew to place the Purifying the Threshing Floor saying at the same point in their narratives indicates that in Anth., too, this saying was a continuation of the Baptist’s prophecy of Someone who would come to administer a wind-and-fire immersion. The author of Mark’s omission of this saying is consistent with his omission of “and fire” in L24.[82] By making these omissions, the author of Mark transformed the impending immersion of judgment into a benevolent immersion in the Holy Spirit, an image that conformed to his understanding that John’s prophecy was fulfilled in Jesus.

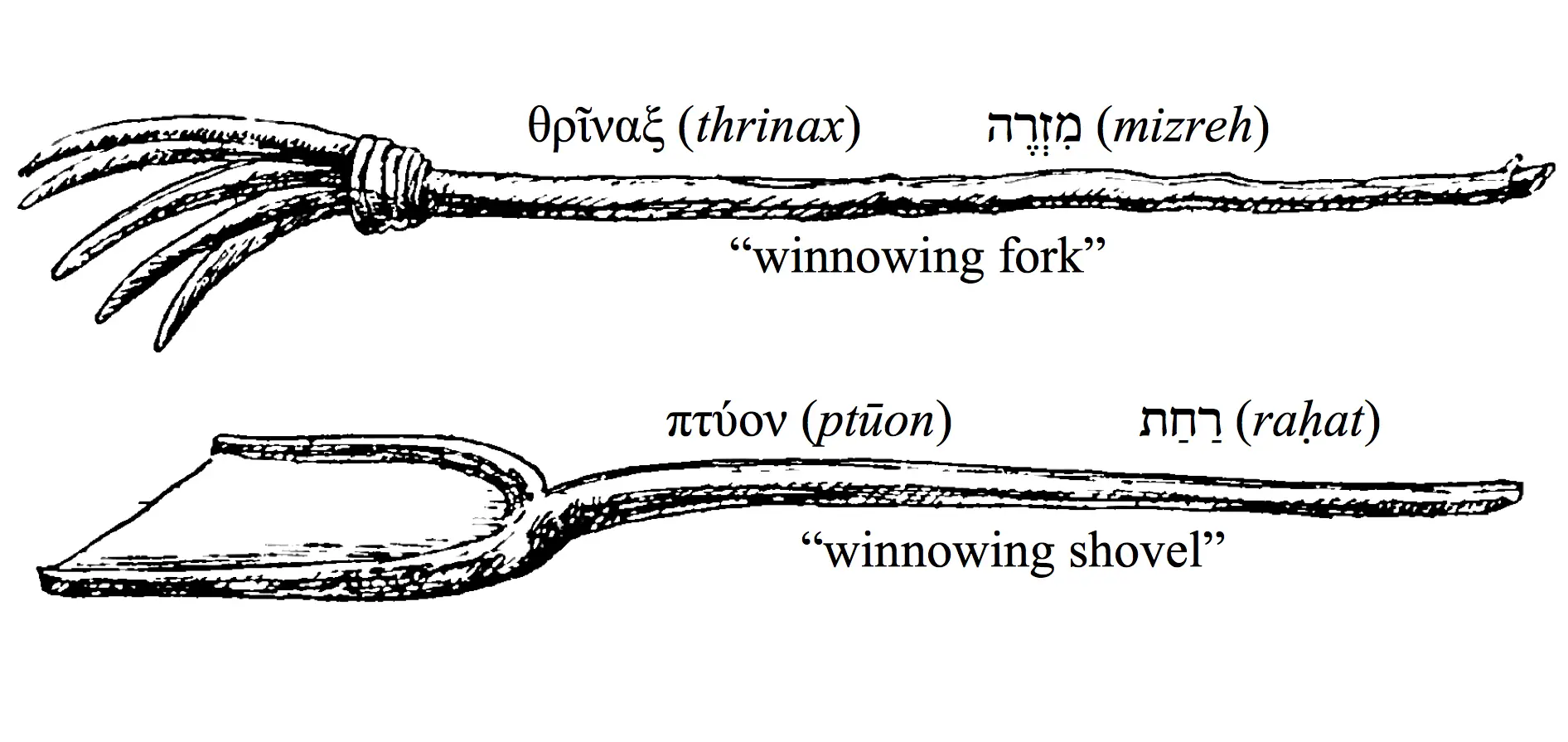

Winnowing tools. Image adapted from Jane E. Harrison, “Mystica Vannus Iacchi (Continued),” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 24 (1904): 241-254, esp. 248.

L25 מִי שֶׁהָרַחַת (HR). On reconstructing ὅς (hos, “who”) with [no_word_wrap]-מִי שֶׁ[/no_word_wrap] (mi she-, “one that”), see above, Comment to L15.

According to Webb, correctly identifying the agricultural implement signified by πτύον (ptūon) is crucial for a proper understanding of the Baptist’s threshing floor imagery.[83] Webb maintained that the winnowing shovel (πτύον) was never used to winnow wheat, this task being reserved exclusively for the winnowing fork (θρῖναξ [thrinax]). According to Webb, the task performed with the winnowing shovel (πτύον) was scooping up the grain from the threshing floor after the winnowing had been completed and moving it into the granary, and scooping up chaff from the threshing floor and heaving it onto the fire.[84] From the fact that the eschatological figure at the threshing floor is said to be holding a πτύον (“winnowing shovel”), Webb deduced that the winnowing process had already been completed by the time of his arrival.[85] That the winnowing process had already been completed, in turn, proved to Webb that the suggestion that John the Baptist predicted an immersion in wind and fire is incorrect. Wind has to do with winnowing, but in order for the eschatological figure to be holding a πτύον, winnowing must have been over and done with. Therefore, Webb concluded, there can be no room for supposing that John the Baptist spoke of an immersion in wind and fire, whereas immersion in the Holy Spirit and fire makes sense. The winnowing shovel could only be used to take the wheat and the chaff to their final destinations: with the shovel the wheat (= the righteous) are immersed in the Holy Spirit, while the chaff (= the wicked) are destroyed in the fire of judgment.[86]

Where Webb’s argument breaks down is not in the identification of the πτύον as a winnowing shovel, but in his assertion that the πτύον was used only for gathering, never for winnowing. That the πτύον was used for winnowing (i.e., separating grain from chaff) and not merely for gathering is suggested by numerous ancient literary sources.

In Homer’s Odyssey we read of a tool that is poetically referred to as a ἀθηρηλοιγός (athērēloigos, “chaff destroyer”; Odyssey 11:127). Since this tool looked similar to a boat oar, it has been identified as a πτύον.[87] But ἀθήρ (athēr, “chaff”), from which the word ἀθηρηλοιγός is derived, refers to light particles that are carried away on the wind. It is the heavier refuse, καλάμη (kalamē, “stubble”) and ἄχυρον (achūron, “straw”), that remains to be scooped up from the threshing floor and burned. In other words, the poetic name ἀθηρηλοιγός (“chaff destroyer”) for the πτύον (“winnowing shovel”) hints that its use was for winnowing as well as gathering.

This conclusion is supported by a reference to the πτύον in the writings of the fifth-century B.C.E. poet Aeschylus, who described a dove at a threshing floor being killed by the shovels.[88] It is more likely that an unwary dove would be killed by shovels during the vigorous process of winnowing than in the gentler process of scooping up grain. Another indication that the πτύον was used for winnowing is the custom of setting up a πτύον in the middle of a grain heap to indicate that the winnowing process was completed.[89]

The Latin and Hebrew equivalents of πτύον provide further support for our conclusion that the winnowing shovel was used for winnowing as well as gathering. The Latin term for πτύον is ventilabrum,[90] which, according to Varro (first cent. B.C.E), earned its name “because with this [i.e., the ventilabrum—DNB and JNT] the grain ventilatur ‘is tossed’ in the air” (Varro, On the Latin Language 5:138; Loeb).[91] That by “tossed in the air” Varro referred to winnowing grain cannot be doubted, since elsewhere he made this explicit:

Iis tritis oportet e terra subiectari vallis aut ventilabris, cum ventus spirat lenis.

After the threshing the grain should be tossed from the ground when the wind is blowing gently, with winnowing fans or shovels [ventilabris]. (Varro, On Agriculture 1:52 §2; Loeb [adapted])[92]

Instances of the Hebrew equivalent of πτύον, which, as Webb correctly noted, is רַחַת (raḥat, “winnowing shovel”),[93] likewise support our contention that the winnowing shovel was used for winnowing. For example, Rabbi Yose cited Rabbi Hanina’s opinion that defined a threshing floor that is not fixed as כל שאינו זורה ברחת (“any [threshing floor] in which a person does not winnow with a winnowing shovel”; b. Bab. Bat. 24b), the implication being that in a regular threshing floor a person does winnow with a רַחַת (“winnowing shovel”). Another rabbinic text leads to the same conclusion:

תנו רבנן המקבל שדה מחבירו ולא עשתה אם יש בה כדי להעמיד כרי חייב לטפל בה שכך כותב לו אנא אוקים ואניר ואזרע ואחצוד ואעמר ואדוש ואידרי ואוקים כריא קדמך ותיתי אנת ותיטול פלגא ואנא בעמלי ובנפקות ידי פלגא וכמה כדי להעמיד בה כרי אמר רבי יוסי ברבי חנינא כדי שתעמוד בו הרחת

Our rabbis taught [in a baraita]: The one who leases a field from his fellow, but it does not produce—if there is enough to make a heap, he is liable to continue working it, for thus it is written for him [in the Aramaic lease agreement]: “I will stand, and I will plow, and I will sow, and I will cut, and I will make into sheaves, and I will thresh, and I will winnow [ואידרי], and I will set up a heap before you, and you will come and receive half, and I will receive half in return for my labor and expenses.” And how much is enough to make a heap? Rabbi Yose in the name of Rabbi Hanina said, “Enough so that you may stand up a shovel [הָרַחַת] in it.” (b. Bab. Metz. 105a; cf. y. Bab. Metz. 9:4 [32b])

We have already encountered the custom of standing up a winnowing shovel in a grain heap in our survey of Greek sources. Here, it is likely that the standing up of the shovel in the grain heap was to signal to the landlord or the tax assessors that the use to which the winnowing shovel had been put—the winnowing process—was now completed.[94] Commenting on this passage, Rashi paraphrased the Aramaic declaration ואידרי (“and I will winnow”) in Hebrew as אזרה המוץ ברחת או בנפה (“I will winnow the chaff with a winnowing shovel [בְּרַחַת] or with a fan”). Similarly, in his commentary on b. Shab. 73a, which defines winnowing as a class of work prohibited on the Sabbath, Rashi wrote: הזורה ברחת לרוח (“‘Winnowing’ [m. Shab. 7:2], i.e., with a winnowing shovel [בְּרַחַת] to the wind”).

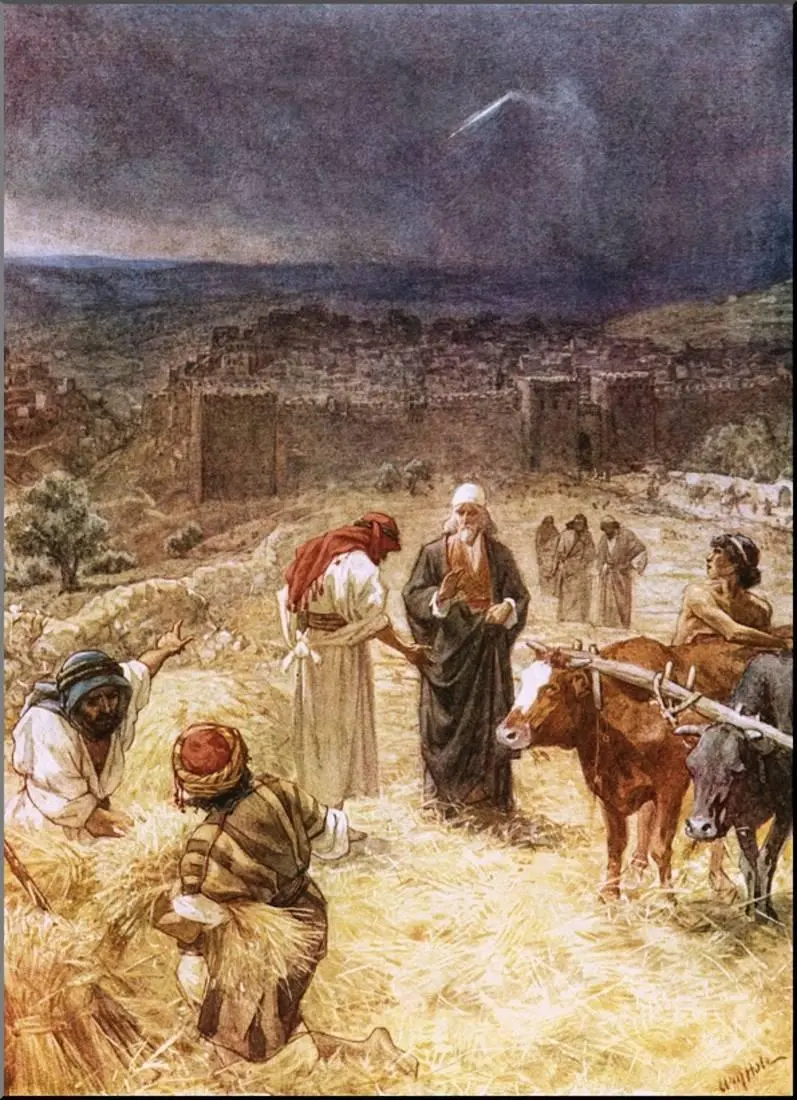

A threshing floor near Mount Gerizim photographed in the early 1900s. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Thus, it emerges from the ancient sources that Webb’s contention that a winnowing shovel was never used for winnowing is false. Winnowing shovels were used at threshing floors to toss the threshed produce into the air, so that the wind could carry the chaff away and the wheat could be separated from the unwanted refuse. Lest the pendulum swing too far in the other direction, however, we must point out that winnowing shovels were also used for scooping up the winnowed grain. The Mishnah specifically refers to the use of the רַחַת in storerooms (m. Kel. 15:5). What we learn about the winnowing shovel from rabbinic sources makes רַחַת the perfect agricultural implement for HR, for in Yohanan the Immerser’s Eschatological Discourse the coming Someone not only winnows (as alluded to by the immersion in wind) but also gathers the larger refuse for the flames (as alluded to by the immersion in fire) and stores the wheat in the storehouse.

L26 בְּיָדוֹ (HR). On reconstructing χείρ (cheir, “hand”) with יָד (yād, “hand”), see Not Everyone Can Be Yeshua’s Disciple, Comment to L35.

L27 καὶ διακαθαριεῖ (GR). Matthew’s verb, διακαθαρίζειν (diakatharizein, “to purge thoroughly”), is not only absent from LXX, it appears to be unattested prior to the writing of his Gospel.[95] The related verb καθαρίζειν (katharizein, “to purify,” “to cleanse”) does occur in LXX, but not in the sense of clearing a threshing floor or winnowing grain. Luke’s verb, διακαθαίρειν (diakathairein, “to purge thoroughly”), is also absent from LXX, but the cognate verb καθαίρειν (kathairein, “to cleanse,” “to purge”) does occur once in LXX as the translation of the root [no_word_wrap]ד-ו-שׁ[/no_word_wrap] (“thresh”; Isa. 28:27). A second-century C.E. papyrus attests to the use of καθαίρειν in the sense of “winnow” or “sift.”[96] Perhaps this is the sense of καθαίρειν in 2 Kgdms. 4:6, the only other instance of καθαίρειν in LXX, which states, ἡ θυρωρὸς τοῦ οἴκου ἐκάθαιρεν πυρούς (“the porter of the house was cleaning wheat”). Moreover, the very same verb that appears in Luke 3:17, διακαθαίρειν, occurs in a scene that takes place at a threshing floor in a writing attributed to Alciphron (date uncertain):

Ἄρτι μοι τὴν ἅλω διακαθήραντι καὶ τὸ πτύον ἀποτιθεμένῳ ὁ δεσπότης ἐπέστη καὶ ἰδὼν ἐπῄνει τὴν φιλεργίαν

I had just finished clearing [διακαθήραντι] the threshing floor and was putting my winnowing shovel [πτύον] away when my master came suddenly upon me, saw what I had done, and proceeded to commend my industry. (Alciphron, Letters 2:23; Loeb [adapted])[97]

We believe the odd verb selection in Matthew’s version of Purifying the Threshing Floor is best accounted for by Notley’s suggestion that the threshing floor in John the Baptist’s saying is a veiled reference to the Temple (see below, Comment to L28). Unlike threshing floors, it is normal to speak of the purification of temples. We suspect that the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua encountered a Hebrew verb that could mean either “purify” or “clear out,” and that the rare verb διακαθαρίζειν,[98] in an attempt to capture the Baptist’s symbolic language of clearing the threshing floor as a metaphor for purifying the Temple. The author of Matthew retained the unusual verb from Anth., whereas the author of Luke substituted the “correct” verb for Anth.’s unusual one.

Thus, it appears that the author of Luke improved Anth.’s wording in L27 in two respects:

- He changed the rare and unusual (for its context) verb διακαθαρίζειν to the more “correct” (from a Greek-speaker’s perspective) διακαθαίρειν.

- He changed the future indicative into an infinitive.[99]

וְיָבוֹר (HR). The Hebrew root ב-ר-ר (b-r-r) can be used in the ritual sense of “purify,” in the metallurgical sense of “refine” or “polish,” in the agricultural sense of “sort” or “clear out,” or in a more generic sense of “select” or “choose.”[100] Of particular interest for our present purposes are the pairing of ב-ר-ר with זָרָה (zārāh, “winnow”) to describe the processing of grain:

רוּחַ צַח שְׁפָיִים בַּמִּדְבָּר דֶּרֶךְ בַּת עַמִּי לוֹא לִזְרוֹת וְלוֹא לְהָבַר׃ רוּחַ מָלֵא מֵאֵלֶּה יָבוֹא לִי

A scorching wind of the bare heights in the desert is in the way of the daughter of my people, not to winnow [לִזְרוֹת] and not to sort [לְהָבַר], a wind too full for these will come to me. (Jer. 4:11-12)

It is not clear from this verse in what sense לְהָבַר (lehāvar) is used, but its close association with “winnow” and its sequence in relation to this verb implies that לְהָבַר is the action that follows winnowing. Perhaps it is the cleaning up process after winnowing, which involved sorting out the grain from the refuse leftover from winnowing.

Another example of pairing of “winnow” with ב-ר-ר is found in the following mishnah:

אֲבוֹת מְלָאכוֹת אַרְבָּעִים חָסֵר אַחַת הַחוֹרֵשׁ הַזּוֹרֵעַ [הַקּוֹצֵר] הַמְעַמֵּר הַדָּשׁ וְהַזּוֹרֶה הַבּוֹרֵר הַטּוֹחֵן הַמַּרְקִיד הַלָּשׁ וְהָאוֹפֶה

The primary categories of work are forty minus one: plowing, sowing, [harvesting], binding into sheaves, threshing, and winnowing [וְהַזּוֹרֶה], sorting [הַבּוֹרֵר], grinding, sifting, kneading, and baking…. (m. Shab. 7:2)

The Mishnah here describes the entire process of raising wheat and turning it into bread. Once again the meaning of הַבּוֹרֵר is not entirely clear. It follows winnowing, so “sorting” or “selecting” the grain from the left over refuse, or “clearing out” the grain from threshing floor is probably what is intended. In any case, בָּרַר seems like the right verb for HR based on the context in which the winnowing process with wind has taken place and the burning up of the stubble in fire is about to happen. The choice of בָּרַר for HR also explains why the Greek translator of the Hebrew Life of Yeshua chose a verb meaning “purify,” since verbs and nouns from the ב-ר-ר root are often synonymous with verbs and nouns from the root ט-ה-ר, as we see in the following examples from DSS:

ואז יברר אל באמתו כול מעשי גבר וזקק לו מבני איש להתם כול רוח עולה מתכמי בשרו ולטהרו ברוח קודש מכול עלילות רשעה

And then God will purify [יברר] with his truth all the deeds of man and refine for himself from the sons of man to put an end to every spirit of perversity within his flesh and to purify him [ולטהרו] with his spirit of holiness from all wicked deeds. (1QS IV, 20-21)

ובקדושים יקדי[ש] אלוהים לו למקדש עולמים וטהרה בנברים והיו כוהנים עם צדקו צבאו ומשרתים מלאכי כבודו

And among the holy ones God will sancti[fy] for himself for an eternal sanctuary and purity [וטהרה] among the purified [בנברים]. And they will be priests, his righteous people, his army and his ministers, angels of his glory. (4Q511 35 I, 2-4)

The use of the root ב-ר-ר in this cultic context (Temple, priests, sanctification and purity) is significant. It proves that John the Baptist could have used ב-ר-ר in two senses, in the agricultural sense for clearing out a threshing floor and in the cultic sense of purifying the Temple, which the threshing floor symbolized.

Alternatives for HR include וִיכַפֵּר (vichapēr, “and he will purify”) and וִיטַהֵר (viṭahēr, “and he will purify”), but neither כִּפֵּר (kipēr, “purify,” “atone”)[101] nor טִהֵר (ṭihēr, “purify”)[102] has the double sense of “clear out” and “purify.”

L28 אֶת גּוֹרְנוֹ (HR). In LXX ἅλων (halōn, “threshing floor”) usually occurs as the translation of גּוֹרֶן (gōren, “threshing floor”).[103] Likewise, the LXX translators nearly always rendered גּוֹרֶן as ἅλων.[104]

In a lecture on John the Baptist’s message, Notley made the insightful suggestion that the threshing floor to which the Baptist referred was a veiled reference to the Temple.[105] The use of a threshing floor as a metaphor for the Temple is natural, since, according to Scripture, the Temple was built on a threshing floor (2 Sam. 24:18-24; 1 Chr. 21:18-22; 2 Chr. 3:1).[106] Moreover, if the inspiration behind John the Baptist’s prediction of the coming Someone who would immerse Israel in wind and fire and purify his threshing floor was Malachi’s prophecy of Elijah’s sudden appearance in the Temple and his purification of the priesthood (Mal. 3:1-5), then the conclusion that the threshing floor is a cipher for the Temple seems unavoidable.

Painting by William Hole depicting David’s purchase of the threshing floor of Aravnah the Jebusite, which later became the site of Solomon’s Temple. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

We have also seen that a purification of the Temple on the eschatological Day of Atonement lines up nicely with John the Baptist’s proclamation of a Jubilee shemiṭāh or release from the indebtedness of sin (see A Voice Crying, Comments to L15 and L36). According to Scripture, the Sabbatical and Jubilee releases of debt were to be proclaimed on the Day of Atonement (Lev. 25:8-12). Therefore, John’s immersions appear to be a preparation for the eschatological Day of Atonement, to ensure that the righteous in Israel would be purified from the defilement of sin. Only by being immersed by John would they endure the day of Elijah’s coming, which, according to Malachi, would be like a refiner’s fire (Mal. 3:2). Purified from sin, the righteous of Israel would be like wheat gathered safely into the storeroom. But those who refused John’s immersion would be caught in an impure state when Elijah came to purify the Temple, and so they would be blown away like chaff or burnt like stubble.

Few scholars besides Notley have noticed that the threshing floor of which the Baptist spoke was a veiled reference to the Temple,[107] but J. Armitage Robinson came very close when he suggested that Jesus’ “cleansing of the Temple” was inspired by John’s prophecy of the purification of the threshing floor.[108] This suggestion was subsequently echoed by his nephew John A. T. Robinson.[109]

If we are correct in supposing that John the Baptist taught that the Temple was so defiled that it required a superhuman figure to purify it on an eschatological Day of Atonement, then the Baptist must have had an exceedingly low opinion of the current state of the Temple and of the priesthood that controlled it. But is there a specific critique of the priesthood implied in the Baptist’s prophecy of a coming Someone who would purify the threshing floor?

The facade of the Jerusalem Temple as depicted in a fresco from the Dura Europos Synagogue. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

One possibility is that John the Baptist anticipated the restoration of the Zadokite line to the high priesthood. Zadok was the high priest in the time of King David, and descendants of Zadok continued to serve as high priests until the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Thus, the Zadokite high priesthood provided continuity between the pre-exilic period and the Second Temple period, a continuity that, in the eyes of some, gave the Second Temple its legitimacy. The removal of the Zadokite line from the high priesthood in the second century B.C.E. was a major disruption, likely leading to the formation of the party of the Sadducees (Hebrew: צדוקים, “Zadokites”) and the foundation of the temple of Onias (a Zadokite priest) in Leontopolis, Egypt.[110] The Essenes, too, looked forward to the renewal of the Zadokite high priesthood,[111] and, given the numerous points of contact between John the Baptist and the Essenes, it is plausible that the Baptist, too, entertained Zadokite sympathies. If the Someone whose coming John the Baptist predicted was Elijah, then we must take into account the ancient Jewish traditions that identified Elijah with Phineas the high priest.[112] According to Num. 25:13, God made a covenant of eternal priesthood (בְּרִית כְּהֻנַּת עוֹלָם) with Phineas, which some ancient Jewish exegetes understood to constitute a promise that the high priesthood should be occupied by a descendant of Phineas forever. The book of Chronicles indicates that Zadok, the founder of the Zadokite high priesthood, belonged to the line of Phineas (1 Chr. 6:8),[113] which makes Elijah-cum-Phineas an appropriate figure for reinstating the Zadokite priesthood.

The function of Elijah as a restorer of the Zadokite high priesthood may be corroborated by a rabbinic source. According to the Mishnah, Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, who was active at the end of the Second Temple period, received the following tradition from his predecessors concerning Elijah’s coming:

אֵין אֵלִייָּהוּ בָּא לְטַמֵּא וּלְטַהֵר לְרָחֵק וּלְקָרֵב אֶלָּא לְרָחֵק אֶת הַמְקוֹרָבִין בִּזְרוֹעַ וּלְקָרֵב אֶת הַמְרוֹחָקִין בִּזְרוֹע

Elijah is not coming to declare pure or impure, or to distance or bring near, but only to remove those [families] who were brought near by force and to reinstate those [families] who were driven out by force. (m. Edu. 8:7)

Although the examples of families that are cited in the continuation of the tradition cited above do not include the high-priestly family of Zadok, one wonders whether the tradition was considered to be applicable to the Zadokite high priesthood as well.

Winnowing at Gezer, Oct. 1934. The man in the foreground uses a winnowing fork, the woman behind him is using a winnowing fan. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Another possibility is that John the Baptist’s critique of the Temple hierarchy was leveled against the high priests’ practice of sending their slaves armed with staves to threshing floors to extort from Israelite farmers the priestly dues, which by rights belonged to the ordinary priests. Josephus described this high-priestly extortion as taking place during the term of Ishmael son of Phiabi, who was appointed by Agrippa II (ca. 49 C.E.; Ant. 20:180-181). Josephus ascribed the same practice to Ananias son of Nedebaeus (Ant. 20:206), who was high priest just prior to Ishmael son of Phiabi, although Josephus indicates that the extortions perpetrated by Ananias took place during Albinus’ term as governor of Judea, which was in the early 60s C.E. These dates are much later than the time of John the Baptist, but Josephus also indicates that such extortion was rampant among all the high priests (Ant. 20:207; cf. Ant. 20:181), so perhaps these extortions were already taking place during the Baptist’s lifetime.[114] An early date for the extortions at the threshing floors seems to be supported by an early rabbinic tradition that condemns the corrupt practices of several high-priestly families, including the house of Boethus, which was in power during the reign of Herod the Great (t. Men. 13:21; b. Pes. 57a). If high-priestly extortion of the priestly dues was the aim of the Baptist’s critique, then his warning had an ironic twist: the coming Someone would purify his threshing floor (i.e., the Temple) by putting a stop to the high-priestly abuses perpetrated at threshing floors throughout the land of Israel.

There is no reason why the two critiques we have suggested should be mutually exclusive.

L29 καὶ συνάξει τὸν σῖτον (GR). As in L27, the infinitive in Luke’s version is a stylistic improvement over the future indicative verb in Matthew’s version of Purifying the Threshing Floor.[115] It therefore seems likely that the author of Matthew copied συνάξει (sūnaxei, “he will gather”) from Anth.[116] Matthew’s version reads “his wheat” as opposed to “the wheat” in Luke’s version. In this instance we suspect that the author of Matthew added the possessive pronoun in order to conform to “his hand” (L26), “his threshing floor” (L28) and “his storehouse” (L30).[117] In this way the contrast is heightened between the grain, which is to be preserved, and the refuse, which is to be destroyed.

וְיַכְנִיס אֶת הַחִטִּים (HR). On reconstructing συνάγειν (sūnagein, “to gather”) with הִכְנִיס (hichnis, “to bring in”), see Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry, Comment to L16.

On reconstructing σῖτος (sitos, “grain”) with חִטָּה (ḥiṭāh, “wheat”), see Darnel Among the Wheat, Comment to L8. Since the Hebrew term for wheat usually occurs in the plural form (one such example is cited below in Comment to L31), we have followed suit in HR.

L30 לְאוֹצָרוֹ (HR). On reconstructing ἀποθήκη (apothēkē, “storehouse”) with אוֹצָר (’ōtzār, “storehouse”), see Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry, Comment to L16.

L31 וְהַקַּשׁ (HR). In LXX ἄχυρον (achūron, “straw”) usually occurs as the translation of תֶּבֶן (teven, “straw”).[118] Although we are accustomed to thinking of the Someone whose coming the Baptist foretold as burning the chaff, there is only one example in LXX where ἄχυρον occurs as the translation of מוֹץ (mōtz, “chaff”; Isa. 17:13). Moreover, chaff was not typically burned. The light particles referred to as מוֹץ were simply carried away on the wind (cf. Isa. 17:13; Hos. 13:3; Ps. 1:4; 35:5; Job 21:18; 1QHa XV, 23). It seems likely, therefore, that by ἄχυρον something larger than chaff is intended.[119]

Hebrew sources refer to three classes of refuse that are left over from the threshing and winnowing process: תֶּבֶן (teven, “straw”), קַשׁ (qash, “stubble”) and מוֹץ (mōtz, “chaff”). All three are mentioned together in the following rabbinic fable:[120]

התבן והמוץ והקש היו מדיינין זה עם זה זה אומר בשבילי נזרעה השדה וזה אומר בשבילי נזרעה השדה אמרו להן החטים המתינו עד שתבא הגורן ואנו יודעין בשל מי נזרעה השדה. בא הגורן וכשנכנסים אל הגורן יצא בעל הבית לזרותה הלך לו המוץ לרוח נטל התבן והשליכו לארץ נטל הקש ושרפו נטל את החטין ועשה אותן כרי

The straw [הַתֶּבֶן] and the chaff [וְהַמּוֹץ] and the stubble [וְהַקַּשׁ] were conversing with one another. This one was saying, “On my account the field was sown!” And that one was saying, “On my account the field was sown!” The wheat [הַחִטִּים] said to them, “Wait until the harvest comes, and we will know on whose account the field was sown.” The harvest came, and as they were brought into the threshing floor the landlord came out to winnow it. The chaff went to the wind. He took the straw and threw it on the ground. He took the stubble and burnt it. He took the wheat and made it into a heap. (Song Rab. 7:3 §3 [ed. Etelsohn, 233]; cf. Gen. Rab. 83:5 [ed. Theodor-Albeck, 2:1000-1001]; Pesikta Rabbati 10:4 [ed. Friedmann, 36a])

This fable not only enumerates the different kinds of refuse that were left over after threshing and winnowing, it also indicates the different means by which the three classes of refuse were disposed of. Chaff was obliterated in the wind.[121] Straw could be put to use for other purposes, such as fodder, fertilizer or ground cover. Stubble (קַשׁ) was used as fuel for fires.[122]

Not only does קַשׁ (“stubble”) appear to be the correct term for the refuse that was burned after winnowing, קַשׁ suits the Baptist’s imagery, which drew so heavily from the prophecies of Malachi, since in Malachi we read:

כִּי־הִנֵּה הַיּוֹם בָּא בֹּעֵר כַּתַּנּוּר וְהָיוּ כָל־זֵדִים וְכָל־עֹשֵׂה רִשְׁעָה קַשׁ וְלִהַט אֹתָם

For behold! The day is coming, burning like an oven. And all the arrogant and workers of wickedness will be stubble [קַשׁ], and it will set them ablaze…. (Mal. 3:19 [ET: 4:1])

L32 יִשְׂרֹף בְּאֵשׁ תָּמִיד (HR). On reconstructing κατακαίειν (katakaiein, “to burn”) with שָׂרַף (sāraf, “burn”), see Darnel Among the Wheat, Comment to L32.

On reconstructing πῦρ (pūr, “fire”) with אֵשׁ (’ēsh, “fire”), see above, Comment to L24.

The adjective ἄσβεστος (asbestos, “unquenchable”) occurs only once in LXX (Job 20:26 [Alexandrinus]), where κατέδεται αὐτὸν πῦρ ἄσβεστον (“unquenchable fire will devour him”; NETS) occurs as the translation of תְּאָכְלֵהוּ אֵשׁ לֹא נֻפָּח (“and a fire not fanned will consume him”). It seems unlikely, however, that John the Baptist alluded to this verse in Job. Reconstructing πυρὶ ἀσβέστῳ (pūri asbestō, “in/with unquenchable fire”) with בְּאֵשׁ תָּמִיד (be’ēsh tāmid, “in perpetual fire”) is in keeping with our supposition that the Baptist’s threshing floor imagery is a veiled reference to the Temple. The phrase אֵשׁ תָּמִיד occurs only once in Scripture, where it describes the flames on the altar:

אֵשׁ תָּמִיד תּוּקַד עַל הַמִּזְבֵּחַ לֹא תִכְבֶה

A perpetual fire shall be kept burning on the altar, it will not be extinguished. (Lev. 6:6 [ET: 6:13])

καὶ πῦρ διὰ παντὸς καυθήσεται ἐπὶ τὸ θυσιαστήριον, οὐ σβεσθήσεται

And a fire through all time will be burned on the altar, it will not be extinguished [σβεσθήσεται]. (Lev. 6:6 [ET: 6:13])

Note that the verb σβεννύναι (sbennūnai, “to extinguish”) in Lev. 6:6 comes from the same root as the adjective ἄσβεστος, which occurs here in L32.

In Yohanan the Immerser’s Question, Comment to L15, we suggested that John the Baptist’s reference to the separation of the wheat from the chaff might best be understood as a figurative way of speaking of a regime change within the Temple’s leadership. A new righteous priesthood (the wheat) would be brought in, while the present corrupt priesthood (the chaff) would be expelled.

Redaction Analysis