Revised: 12-Apr-2013

In 1981 I traveled to several cities in the United States and gave a talk entitled “Remez: Hinting at Scripture.”[1] As part of that talk, I said something similar to the following:

One of the basic, Jewish techniques of teaching in the time of Jesus involved the use of רֶמֶז (remez), which is the Hebrew word for “hint” or “allusion.” Jewish teachers, instead of fully quoting verses of Scripture, commonly alluded to the passages upon which their lessons were based. By using the remez technique, a teacher conveyed a great deal of information with remarkable brevity, in much the same way a poet can express complex ideas through metaphors.

The rabbis could teach in this manner because most Jews of the period—and certainly all disciples of sages—were well-versed in the Torah, the Prophets and the Writings. The substance of an allusion sometimes was found in a passage immediately before or after the verse at which the teacher had hinted. To quote the entire passage was unnecessary since most in the audience had learned large segments of Scripture by rote. The moment a teacher made an allusion, the whole passage flashed across the mind’s eye of the biblically literate listener.

One finds numerous examples of remez in the Gospels. Many Christians, however, lack the scriptural background such a technique assumes. As a result, they run the risk of missing the subtler aspects of Jesus’ teachings.

John the Baptist used remez when he asked Jesus, “Are you the coming [one]?” (Luke 7:20; Matt 11:3). John hinted at “The Coming One” of Malachi 3:1 and Zechariah 9:9. Jesus responded in like manner: “The blind receive their sight, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are brought back to life and the poor have the good news preached to them.” Jesus’ answer contained hints at Isaiah 29:18, 35:5-6, 42:7 and 61:1. The allusions John and Jesus made were not solely for economy of words. The hinting constituted a sophisticated way of commenting upon Scripture….[2]

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

I suspect that my unfortunate choice of wording may have played a role in encouraging others to zero in on this term and advance novel ideas concerning its relevance for studying the Gospels. For example, describing remez as belonging to the “four basic modes of Scripture interpretation used by the rabbis,” and then referring to these four by the acronym Pardes, one popular Bible commentator unwittingly has linked remez to a medieval system of scriptural interpretation.[3] Irrespective of his definition for the word, labeling remez as the “r” in Pardes associated it with kabbalistic trends.[4] The earliest sages, who were known as the tannaim, did not speak of four modes of scriptural interpretation. Rather, they initially enumerated seven hermeneutical principles.

Israel’s ancient sages never included remez among their methods, modes or principles of Scripture interpretation. While they did speak about words or phrases from Scripture being a remez to various things, such as the resurrection of the dead, they employed it to mean basically “an allusion to” or “a hint of.” To label remez as a formal hermeneutical principle in the period to which the earliest sages belonged, invests the word with meaning it would carry only at a later time.

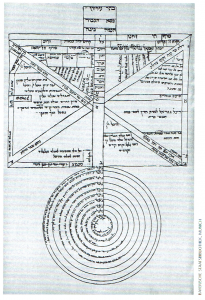

A representation of the ten Sefirot (the stages of emanation that form the realm of God’s manifestation), with their corresponding angelic camps and astronomical spheres extending to earth. From a miscellany that probably originated in Italy about 1400 C.E. Cod. Hebr. Ms. 119, fol. 5v.

Hillel, a contemporary of Herod the Great, compiled a list of seven hermeneutical principles.[5] A century later, Rabbi Yishmael expanded this list to thirteen,[6] and Rabbi Eliezer ben Yose the Galilean further expanded the list to thirty-two.[7] None of these lists includes remez, or for that matter, the other three modes of kabbalistic scriptural interpretation included in the acronym Pardes—peshat, derash and sod.

The earlier sages had not employed a method of scriptural interpretation that carried the formal designation remez. A thousand years later, however, the situation changed once highly influential mystical trends began reshaping rabbinic Judaism. The late-thirteenth-century Kabbalists designated one of their distinctive mystical modes of interpretation as remez.

When collectively referring to these interpretive modes, students of the Kabbalah speak of Pardes (literally, “garden,” i.e., “the Garden of the Torah”), which is an acronym derived from the initial letter of each of the four terms (p-r-d-s).[8] The literal meanings of these four Hebrew words—peshat (simple, plain; i.e., the literal), remez (hint, allusion; i.e., the allegorical), derash (homily, sermon; i.e., the homiletic) and sod (secret; i.e., the mystical)—offer little assistance for understanding how these four modes of interpretation functioned within the kabbalistic system. According to the late Professor Gershom Scholem, pioneer researcher in the field of Kabbalah, Moses ben Shem Tov of Leon was the first-known writer to mention the acronym Pardes. He did so about 1290 in a composition entitled Sefer Pardes.[9] Moses ben Shem Tov also wrote The Zohar, which became the most influential work of the Spanish Kabbalists.[10]

The Kabbalists were mystics par excellence, and they pursued vigorously Scripture’s concealed meanings. They aspired to an elevated spiritual awareness by gaining access to concealed knowledge through scrutinizing each letter of the biblical text and through ecstatic ascents into heaven. For instance, on the basis of their distinctive beliefs, they probed the creation of the world; the ascent to and passage through the seven palaces in the uppermost of the firmaments; the contents of each of the seven palaces; the measurements and secret names of the body parts of the Creator; and the names of angels and of God. Their longing for esoteric knowledge may be traced back in part to earlier Gnostic speculations. Such speculations left their imprints on the Kabbalah.[11]

The Tetragrammaton written magically, with each letter containing several radiating circles of light (“eyes”). From Moses Cordovero, Pardes Rimmonim (Cracow, 1592).

Jesus and other personalities of the New Testament made manifold allusions to Scripture. In Hebrew, the word for “allusion” or “hint” is remez. From my reading of early rabbinic texts, to describe remez as a mode of Scripture interpretation or a hermeneutical principle runs the risk of inaccurately representing the language of the sages. To assign remez a place among first-century hermeneutical principles while including it as one of the four components of Pardes constitutes a glaring anachronism. The acronym Pardes belongs exclusively to the domain of the Kabbalah.

Sidebar: David Stern Responds[12]David Bivin believes that I have erred by using the “PaRDeS method” of Bible interpretation, which was developed in the Middle Ages, to deal with biblical texts written long before, and that by so doing I have unwittingly encouraged people to pursue kabbala. I see things differently, but first let me indicate points on which we agree. First, as Bivin acknowledges in footnote 4, we agree that kabbala is a form of mysticism based on Gnostic and other occult and nonbiblical importations into Judaism and thus to be given no credibility. Second, I have no reason to doubt Gershom Scholem’s conclusion that the acronym PaRDeS, used as a mnemonic for remembering the words p’shat, remez, drash and sod, dates from the Middle Ages, and that it was the kabbalists who developed PaRDeS into an exegetical method. But even though these four ways of dealing with a text were systematized by the kabbalists, they existed long before. A computer search of early rabbinic literature—Talmud, Midrash Rabbah, Mekhilta, Sifra, Sifre and the like, a good deal of which dates from the first century and earlier—yielded dozens of examples of the rabbis pointing out a remez in just the senses in which Bivin and I have used the term. Therefore I think he is wrong in writing that “Israel’s ancient sages never included remez among their methods, modes or principles of Scripture interpretation.” In fact, his next sentence proves the opposite. And the following sentence implies I said something I didn’t say: I did not declare remez a “formal hermeneutical principle”; what I do say is that the New Testament writers, like their contemporaries among the rabbis, made use of p’shat, drash(or midrash), remez and sod. Likewise, I have never said that when the New Testament was written PaRDeS constituted a hermeneutical system like the principles of Hillel, Ishmael and Eleazar ben Yose the Galilean. More relevant for my approach is what has happened to PaRDeS in more recent times: it has become part of the standard equipment of Jewish biblical interpretation without having kabbalistic overtones. Any student at a yeshiva will encounter the four terms of PaRDeS in the normal pursuit of his studies, even in institutions which eschew kabbala. In these settings “PaRDeS” is only a mnemonic; and its meaning, “garden,” is used only to help remember the acronym. Clearly the New Testament writers employed ways of dealing with Tanakh texts in addition to the historical-grammatical-linguistic method recognized by modern scholars (which is approximately what is meant by the p’shat). My note to Mattityahu (Matthew) 2:15 on pages 11-14 of the Jewish New Testament Commentary points out that when the author writes that Yeshua’s leaving Egypt to return to the Land of Israel “fulfilled” the citation from Scripture, “Out of Egypt I called my son” (Hosea 11:1), Mattityahu was making use of a remez. The p’shat of Hosea 11:1 is that “my son” refers to the people of Israel and alludes to Exodus 4:22; the prophet is not speaking about Yeshua at all. It is Mattityahu, not Hosea, who operates on the prophet’s text and sees in it a hint of Yeshua. There needs to be a word for talking about such things. The word is remez. I don’t think David Bivin needs to apologize for using this word. And he certainly shouldn’t feel guilty of having promoted kabbala (I don’t). Moreover, I do not grant the kabbalists exclusive possession of the “garden” (PaRDeS) any more than I grant the New Agers possession of the rainbow, which God set in the sky as a sign for Noah—what right do the New Agers have to take it away from Bible-believers and claim it for themselves? Likewise, many biblical feasts have pagan historical origins. There is no shame in using an acronym developed by kabbalists to remember four ways of interpreting texts which have been used widely since before the time of Yeshua. I think this whole matter is a non-problem. My only caveat here would be that we ought not to stop with PaRDeS or make it an exclusive system—this inhibits thought instead of promoting it. Rather, we should consider all relevant ways to understand God’s word to humanity, including and going beyond PaRDeS. Let me close by thanking David Bivin, whom I have known since 1974, when I met him on my first visit to Israel, for offering me the opportunity to respond to his article where it appears. Sidebar: Rev. John Fieldsend RespondsI take the point of David Bivin’s article, and fundamentally I would agree with much of his thesis. However I believe that in his criticism of my article ‘Pardes’ in our Journal of the same name he has not fully noted the context of the point he is seeking to refute. The basic thesis of my article was laid out in the following section:

I then went on to acknowledge that the actual detail and terminology of “Pardes” were not developed until the Middle Ages, but I argued that the detail of such methodologies are rarely developed in a vacuum, but are usually the categorisation of ideas already in common usage.

If my thesis had been as Bivin presented it, I would be the first to agree with its refutation. However I have to say that he has taken one sentence out of the conclusion of my whole article—”We have, in understanding…”—and used it to criticise my whole thesis by taking one section out of its fuller context. |

Notes

- ”Remez: Hinting at Scripture” was one of the lectures delivered as part of a seminar that I conducted in several U.S. cities in 1981. Two years later I co-authored Understanding the Difficult Words of Jesus. This book contains no reference to remez. I included the “remez” lecture on one of the audio cassettes in the “Reading the Gospels Hebraically” teaching series.[↩]

- I repeated this lecture during the speaking tour, both before and after it was recorded. As I developed the presentation, I adapted the wording. Nevertheless, its essence remained identical to this quotation.[↩]

- David H. Stern, Jewish New Testament Commentary (Clarksville, MD: Jewish New Testament Publications, 1992), 11-12. I use the word “unwittingly” because elsewhere in his commentary, Stern distances himself from the Kabbalah. For example, in his comment on 1 Tim. 4:1, Stern writes: “What kinds of ‘deceiving spirits and things taught by demons’ are they ‘paying attention to’?…For the moment, confining ourselves only to religions, we may note: (1) Eastern religions…(9) The occult, including astrology, parapsychology, kabbalah (the occult tradition within Judaism). Why do people turn to these substitutes for the truth…?” (Jewish New Testament Commentary, 643). Stern is not alone in attributing the four-fold kabbalistic system of interpretation—פְּשָׁט (peshat), רֶמֶז (remez), דְּרָשׁ (derash) and סוֹד (sod)—to Jesus and other sages of his time. Despite the anachronism and kabbalistic link, other Christian educators do the same. For example, John Fieldsend, director of The Centre for Biblical and Hebraic Studies, which was established by Prophetic Word Ministries Trust of Moggerhanger, England, and editor of its journal, Pardes, has described in detail the component methodologies of “Pardes”—peshat, remez, derash and sod. As part of his conclusion, he wrote: “We have, in understanding the use of PARDES, a tool that can help us read the Scriptures with something of the mind of those whom God used to write them” (“Hermeneutics and the Significance of the Acronym ‘Pardes,'” Pardes 3.1 [Feb. 1999]: 16). Only if post-talmudic Jewish mystics wrote the New Testament can I imagine this statement to be pertinent.[↩]

- Stern elsewhere has referred to remez as “a hint of a very deep truth” (Jewish New Testament Commentary, p. 12). He also has written: “…behind Hosea’s p’shat was God’s remez to be revealed in its time and lends credibility to the ‘PaRDeS’ mode of interpretation” (p. 13). Stern has suggested that remez is behind Matt 2:15 (pp. 11-14); 2:18 (p. 14); 21:2-7 (pp. 61–62); Mark 12:29 (pp. 96-97); Luke 10:15 (p. 121); Jn. 6:70 (p. 174); Rom. 15:3-4 (p. 436); and Gal. 3:8 (p. 544). Whether discussing the words of Jesus, the words of a Gospel writer, or the words of a writer of an epistle, he refers the reader back to his note at Matt 2:15 where he originally defined remez. In the New Testament and the Dead Sea Scrolls, one can find cases where interpreters viewed biblical passages as having been unclear at the time of their composition, but now entirely intelligible to them (e.g., 1 Pet. 1:10-12; 1 QpHab 7.4). To call this remez, however, imports a Medieval mystical hermeneutical technical term and its distinctive associations into the first century. Are inkwell and quill a word processor?[↩]

- Jerusalem Talmud, Pesahim 6.1, 33a; Tosefta, Sanhedrin 7:11. The seven hermeneutical principles attributed to Hillel are: 1. קל וחומר(kal vaHomer; simple and complex): inference from minor to major case (the “how much more so” principle); 2. גזירה שווה (gezerah shavah; equal commandment): two biblical commandments having a common word or phrase are subject to the same regulations and applications; 3. בנין אב מכתוב אחד (binyan av mikatuv eHad; a sweeping principle [derived] from one scriptural passage): one scripture serves as a model for the interpretation of others, so that a legal decision based on the one is valid for the others; 4. בנין אב משני כתובים (binyan av mishne ketuvim; a sweeping principle [derived] from two scriptural passages): two scriptures having a common characteristic serve as a model for the interpretation of others, so that a legal decision based on the two is valid for the others; 5. כלל ופרט ופרט וכלל (kelal uferat uferat ukelal; general and particular, or particular and general): one scripture, general in nature, can be interpreted more precisely by means of a second scripture that is specific, or particular, in nature, and vice versa; 6. כיוצא בו במקום אחר (kayotse bo bemakom aHer; like that in another place): the interpretation of a scriptural passage by means of another passage having similar content; 7. דבר הלמד מענינו (davar halamed me’inyano; a thing that is learned from the subject): an interpretation of a scripture that is deduced from its context.[↩]

- At the beginning of Sifra. For an excellent description of Yishmael’s thirteen hermeneutical principles, see Louis Jacobs, “Hermeneutics,” Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1972), 8:366-372. See also, Menachem Elon, “Interpretation,” Encyclopaedia Judaica 8:1419-1422.[↩]

- Mishnat Rabbi Eliezer. For a description of Eliezer ben Yose’s hermeneutical principles, see H. L. Strack and Günter Stemberger, Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash (2nd ed.; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 22-30. See also Barnet David Klien, “Baraita of 32 Rules,” Encyclopaedia Judaica 4:194-195.[↩]

- Note the similarity of Stern’s wording: “These four methods of working a text [peshat, remez, derash, sod] are remembered by the Hebrew word ‘PaRDeS,’ an acronym formed from the initials: it means ‘orchard’ or ‘garden'” (Jewish New Testament Commentary, 12).[↩]

- Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (3rd ed.; New York: Schocken Books, 1974), 400; idem, “Kabbalah,” Encyclopaedia Judaica 10:623.[↩]

- Idem, “Kabbalah,” 532. Moses ben Shem Tov wrote The Zohar between 1280 and 1286.[↩]

- Joseph Dan, “Midrash and the Dawn of Kabbalah,” in Midrash and Literature (eds. G. Hartman and S. Budick; New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986), 135, 137. See also Louis Ginzberg, On Jewish Law and Lore (New York: Atheneum, 1970), 188, 190, 192-193. Note Scholem’s statement: “Their [the Kabbalists’] vocabulary and favorite similes show traces of Aggadic influence in proportions equal to those of philosophy and Gnosticism; Scripture being, of course, the strongest element of all” (Major Trends, 32).[↩]

- Born in Los Angeles in 1935, David H. Stern earned a Ph.D. in economics from Princeton University, was a professor at UCLA, mountain-climber, co-author of a book on surfing, and owner of health-food stores. In 1975 he received a Master of Divinity degree from Fuller Theological Seminary. In 1979 he and his family “made aliyah” (immigrated to Israel). Stern’s New Testament translation, Jewish New Testament, is widely circulated, and his 930-page commentary on this translation, Jewish New Testament Commentary, is one of several books he has written.[↩]