How to cite this article:

David N. Bivin and Joshua N. Tilton, “Praying Like Gentiles,” The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction (Jerusalem Perspective, 2017) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/16878/].

Matt. 6:7-8[1]

Revised: 18 January 2026

וּבַתְּפִלָּה אַל תְּפַטְפְּטוּ כַּגּוֹיִם שֶׁהֶם סְבוּרִים שֶׁבְּרֹב דִּבְרֵיהֶם יִשָּׁמְעוּ אַל תִּהְיוּ כָּהֵם כִּי יָדַע אֲבִיכֶם אֵי זֶה צוֹרֶךְ יֵשׁ לָכֶם לִפְנֵי שֶׁאַתֶּם שׁוֹאֲלִים מִמֶּנּוּ

“And don’t blather while you pray as the Gentiles do, since they believe that by uttering pre-formulated incantations their prayers will be granted. So don’t imitate them, for your father knows what you need even before you ask him.”[2]

| Table of Contents |

|

3. Conjectured Stages of Transmission 5. Comment 8. Conclusion |

Reconstruction

To view the reconstructed text of Praying Like Gentiles click on the link below:

| “How to Pray” complex |

| Lord’s Prayer ・ Praying Like Gentiles ・ Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry ・ Persistent Widow parable ・ Friend in Need simile ・ Fathers Give Good Gifts simile |

Story Placement

Jesus’ critique of Gentile prayer is unique to the Gospel of Matthew. In Matthew this critique appears in a discussion of the proper performance of three major religious duties: almsgiving (Matt. 6:1-4), prayer (Matt. 6:5-15) and fasting (Matt. 6:16-18). Each discussion begins with a contrast between those whom Jesus calls “hypocrites,” who seek congratulation for their religious observance from their fellow human beings, and those who perform their religious duties out of true devotion. The latter, according to Jesus, are those whom God will reward. The section on prayer is the longest of the triad because the author of Matthew supplemented the section on prayer with the addition of the Praying Like Gentiles pericope (Matt. 6:7-8), the Lord’s Prayer (Matt. 6:9-13) and an elaboration on the need to forgive others in order to receive forgiveness from on high (Matt. 6:14-15).

That Praying Like Gentiles (Matt. 6:7-8) was originally a distinct unit, which the author of Matthew inserted into its present context in the Sermon on the Mount, has long been recognized by scholars.[3] Catchpole conveniently summarized the arguments as follows:

- The parallelism between the imperative (“do not blather”) and the justification (“because they think they will be heard on account of their many words”) marks Praying Like Gentiles as a self-contained literary unit.

- The group being criticized in Praying Like Gentiles (namely, non-Jews) is different from the group being criticized in the discussion of the proper performance of almsgiving, prayer and fasting (namely, self-aggrandizing Jews).

- The grounds for criticism are different. Whereas Jesus charges the self-aggrandizing Jews with hypocrisy, he charges the Gentiles with ignorance.

- Whereas the discussion of the proper performance of almsgiving, prayer and fasting contrasts the kind of reward (human congratulation vs. divine approval) one might receive for the performance of these religious duties, as well as the time for the enjoyment of these rewards (in the present time vs. in the world to come), Praying Like Gentiles does not discuss rewards at all.[4]

Despite its artificial position within the Sermon on the Mount, the Praying Like Gentiles pericope probably did originally belong to an extended teaching unit on prayer, which also included the Lord’s Prayer, Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry (Matt. 6:25-34 ∥ Luke 12:22-31), the Persistent Widow parable (Luke 18:1-8), and the Friend in Need (Matt. 7:7-8 ∥ Luke 11:5-10) and Fathers Give Good Gifts similes (Matt. 7:9-11 ∥ Luke 11:11-13). We refer to this extended teaching unit on prayer as the “How to Pray” complex.

The fact that Praying Like Gentiles overtly deals with prayer automatically makes it a likely candidate for inclusion in the “How to Pray” complex. Strengthening our hypothesis that Praying Like Gentiles originally belonged to this conjectured literary complex are the strong points of similarity (see below) between Praying Like Gentiles and Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry, a pericope that seems to address the anxieties occasioned by the petition for bread (Matt. 6:11 ∥ Luke 11:3) in the Lord’s Prayer, with its implied commitment to rely on God, rather than one’s own resources or labor, for one’s daily needs. In addition, the classification of prayer as a kind of asking (αἰτεῖν), which is common to Praying Like Gentiles (L10; Matt. 6:8), Friend in Need (L22; Matt. 7:7 ∥ Luke 11:9) and Fathers Give Good Gifts (L20; Matt. 7:11 ∥ Luke 11:13), supports our hypothesis that Praying Like Gentiles and these other pericopae dealing with prayer originally comprised a single literary unit. Further support for our hypothesis is found in the reiteration of God’s foreknowledge of the disciples’ needs (ὧν χρείαν ἔχετε; Matt. 6:8) in Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry (χρῄζετε τούτων; L54; Matt. 6:32 ∥ Luke 12:30), which is then echoed in the Friend in Need simile (ὅσων χρῄζει; L20; Luke 11:8).

The verbal and thematic ties linking Praying Like Gentiles to Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry are particularly strong. Both pericopae critique improper styles of praying/seeking[5] (Matt. 6:7; Matt. 6:32 ∥ Luke 12:30); both pericopae use the conduct of Gentiles as a negative foil to the disciples’ proper conduct (Matt. 6:7; Matt. 6:32 ∥ Luke 12:30); both contain a statement about God’s foreknowledge of human needs (Matt. 6:8; Matt. 6:32 ∥ Luke 12:30); and both pericopae express confidence in God’s willingness to provide on the basis of his paternal relationship to the disciples (Matt. 6:8; Matt. 6:32 ∥ Luke 12:30). These strong similarities suggest that these two pericopae originally appeared in the same literary context. Indeed, the assurance that the heavenly father knows the needs of the disciples before they ask him (Matt. 6:8) may have been the grounds for Jesus’ exhortation not to worry (διὰ τοῦτο λέγω ὑμῖν μὴ μεριμνᾶτε; Matt. 6:25 ∥ Luke 12:22). Thus, our placement of the Praying Like Gentiles pericope between the Lord’s Prayer and Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry fills a logical gap that would otherwise have undermined the inner coherence of the “How to Pray” complex.

For an overview of the entire “How to Pray” complex, click here.

.

.

Click here to view the Map of the Conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua.

.

.

Conjectured Stages of Transmission

It is unlikely that the Praying Like Gentiles pericope was the product of Matthean composition,[6] since it has themes and vocabulary (e.g., the father’s foreknowledge of the disciples’ needs; the improper behavior of Gentiles) in common with pericopae that stemmed from the Anthology (Anth.), the Hebraic-Greek source that was utilized by the authors of Matthew and Luke.

It is unlikely that the Praying Like Gentiles pericope was the product of Matthean composition,[6] since it has themes and vocabulary (e.g., the father’s foreknowledge of the disciples’ needs; the improper behavior of Gentiles) in common with pericopae that stemmed from the Anthology (Anth.), the Hebraic-Greek source that was utilized by the authors of Matthew and Luke.

The author of Luke likely omitted this pericope out of sensitivity to his Gentile audience. The author of Matthew, on the other hand, did not refrain from including critical statements concerning Gentiles despite his anti-Jewish bias and his Gentile-inclusive policy. It appears that the Matthean community regarded itself as neither Jewish nor Gentile, but as a new race, the “true Israel,” made up of believers of all backgrounds, which had supplanted “Israel according to the flesh” as God’s chosen people.[7] Its “neither fish nor fowl” self-understanding allowed the Matthean community to criticize both Jewish and Gentile practices that it deemed unworthy of true religion.

Crucial Issues

- In light of the Praying Like Gentiles pericope, how should we characterize Jesus’ view of non-Jews?

- How should Jesus’ view of non-Jewish religious practices inform our view of Judaism?

Comment

L1 προσευχόμενοι δὲ (GR). In Lord’s Prayer (L9) we reconstructed ὅταν προσεύχησθε (hotan prosevchēsthe, “when you might pray”) as כְּשֶׁאַתֶּם מִתְפַּלְּלִים (keshe’atem mitpalelim, “when you are praying”). Although it would be possible to reconstruct προσευχόμενοι δέ (prosevchomenoi de, “and praying”) the same way, the difference in Greek phrasing suggests that we ought to seek an alternative Hebrew reconstruction. In the Mishnah we encounter a few examples where בַּתְּפִילָּה (batefilāh, “in the prayer”) is used in the sense of “while praying”:

הָאֻמָּנִים קוֹרִין בְּרֹאשׁ הַאִילָּן אוֹ בְרֹאשׁ הַנִּדְבָּךְ מַה שֶּׁאֵינָן רַשַּׁיִים לַעֲשׂוֹת כֵּן בַּתְּפִילָּה

Craftsmen may recite [the Shema] while in a treetop or on top of a course of stones, which they are not permitted to do while praying [the Amidah] [בַּתְּפִילָּה]. (m. Ber. 2:4)

הָיָה עוֹמֵד בַּתְּפִילָּה וְנִזְכַּר שֶׁהוּא בַעַל קֶרִי

If he was standing while praying [the Amidah] [בַּתְּפִילָּה] and he remembered that he was ritually impure…. (m. Ber. 3:5)

עָמְדוּ {לפניהם} בִתְפִּילָּה וּמּוֹרֵידֵין לִפְנֵי הַתֵּיבָה זָקֵן וְרָגִיל וְיֶשׁ לוֹ בָנִים וּבֵיתוֹ רֵיקָּם כְּדֵי שֶׁיְּהֵא לִבּוֹ שָׁלֵם בַּתְּפִילָּה

They stood {before them} while praying [בִתְפִּילָּה] and they sent down before the ark an experienced elder who had children and whose house was empty so that his heart would be wholly focused while praying [בַּתְּפִילָּה]…. (m. Taan. 2:2)

A similar usage of בַּתְּפִילָּה is attested in the book of Daniel, where we read:

וְעוֹד אֲנִי מְדַבֵּר בַּתְּפִלָּה וְהָאִישׁ גַּבְרִיאֵל אֲשֶׁר רָאִיתִי בֶחָזוֹן בַּתְּחִלָּה מֻעָף בִּיעָף נֹגֵעַ אֵלַי

And I was still speaking while in prayer [בַּתְּפִלָּה], when the man Gabriel, whom I had seen in a vision at the beginning, came swiftly flying up to me. (Dan. 9:21)

On the basis of these examples we have adopted בַּתְּפִלָּה for HR.

L2 μὴ βατταλογήσητε (GR). The verb βατταλογεῖν (battalogein; var. βαττολογεῖν [battologein]) is extremely rare in extant Greek sources.[8] Apart from Matt. 6:7 and the later Christian writers who made reference to this verse, only two other instances of βατταλογεῖν are known. The first of these is found in a biography of Aesop, where we read:

ἐν οἴνῳ μὴ βαττολόγει σοφίαν ἐπιδεικνύμενος

Through wine do not babble [μὴ βαττολόγει], demonstrating wisdom. (Vita Aesopi chpt. 19 [ed. Westermann, 46-47])[9]

The second known instance of βατταλογεῖν unrelated to NT occurs in a commentary on the works of Epictetus by the sixth-century C.E. philosopher Simplicius of Cilicia, where we find:

Ἀλλ’ ἐπὶ τὰ λοιπὰ κεφάλαια τοῦ Ἐπικτήτου τρεπτέον, μὴ ἐμαυτὸν λάθω προθέμενος μὲν τὰ τοῦ Ἐπικτήτου σαφηνίσαι, περὶ καθηκόντων δὲ βαττολογῶν νῦν.

I must turn to the other chapters of Epictetus’s book, and I must not forget my purpose, while I babble [βαττολογῶν] about duties. (In Epicteti Enchiridion, chpt. 37 end)[10]

Due to the paucity of examples, some scholars have suggested that βατταλογεῖν is in fact a hybrid term made up of Hebrew/Aramaic (βαττα = בָּטָא [bāṭā’, “speak rashly”]?; or βατταλ = בִּטֵּל [biṭēl, “nullify”]?) and Greek components (λογεῖν [logein, “to speak”]).[11] These hybrid explanations fail to convince most scholars, however. First, it is difficult to understand why a Greek translator of a Semitic source would have had no other recourse than to coin a hybrid term, which, because it was unknown, could have conveyed no meaning to a Greek-speaking audience. Second, the two other sources where βατταλογεῖν does occur lack a Hebrew or Aramaic substratum, and it is difficult to understand why these Greek authors would have used a basically unknown Semitic-Greek hybrid term in their writings.[12]

The comments of Origen on Matt. 6:7 also caution against tracing βατταλογεῖν to a Semitic-Greek hybrid term. In his treatise On Prayer (ca. 234 C.E.),[13] Origen wrote the following about the term βατταλογεῖν:

καὶ ἔοικέ γε ὁ πολυλογῶν βαττολογεῖν, και ὁ βαττολογῶν πολυλογεῖν.

It seems indeed that he who speaks much “uses vain repetitions [βαττολογεῖν],” and he who “uses vain repetitions [βαττολογῶν]” speaks much. (Origen, De oratione [On Prayer] 21:2 [ed. Koetschau, 2:345])[14]

Origen’s comment reveals that the verb βατταλογεῖν was rare enough to warrant some explanation, but he does not treat this verb the way he treated the notoriously difficult adjective ἐπιούσιος (epiousios) that occurs in the Lord’s Prayer (L16; Matt. 6:11 ∥ Luke 11:3), about which he wrote:

πρῶτον δὲ τοῦτο ἰστέον, ὅτι ἡ λέξις ἡ ,,ἐπιούσιον“ παρ᾽ οὐδενὶ τῶν Ἑλλήνων οὔτε τῶν σοφῶν ὠνόμασται οὔτε ἐν τῇ τῶν ἰδιωτῶν συνηθείᾳ τέτριπται, ἀλλ᾽ ἔοικε πεπλάσθαι ὑπὸ τῶν εὐανγγελιστῶν.

And first, it ought to be known that this word epiousios is not employed by any of the Greeks or learned writers, nor is it in common use among ordinary folk; but it seems likely to have been coined by the evangelists. (De oratione [On Prayer] 27:7 [ed. Koetschau, 2:366-367])[15]

The sanctuary of the god Pan in Banias at the headwaters of the River Jordan as it appeared to an artist in the mid-1800s. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Had βατταλογεῖν been derived from Hebrew or Aramaic, or had it been coined by the Greek translator of a Hebrew or Aramaic Gospel, Origen would hardly have failed to state this fact, as his discussion of ἐπιούσιος shows. It therefore seems best to regard βατταλογεῖν as a purely Greek verb rather than as a hybrid Hebrew/Aramaic-Greek term coined by the Greek translator of Jesus’ saying.

Defining βατταλογεῖν is also problematic due to its few attestations. “To go on and on at length” would seem to fit the examples in Matt. 6:7, Vita Aesopi and Simplicius. Some scholars have suggested that βατταλογεῖν is related to βατταριζεῖν (battarizein, “to stutter”).[16] In any case, βατταλογεῖν seems to connote redundancy and incoherence.

אַל תְּפַטְפְּטוּ (HR). Since the verb βατταλογεῖν is so rare, and since its exact meaning is so uncertain, finding a suitable reconstruction is difficult. Delitzsch rendered βατταλογεῖν as פִּטְפֵּט (piṭpēṭ, “babble,” “blather”) in his Hebrew translation of the New Testament. More recently, Luz considered the Aramaic cognate פַּטְפֵּט (paṭpēṭ, “babble,” “blather”) to be a possible equivalent of βατταλογεῖν.[17] The Hebrew verb פִּטְפֵּט is quite rare in rabbinic sources, and if this was the verb that stood in the conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua it might account for the choice of an equally rare verb in Greek. We encounter an example of פִּטְפֵּט in the following baraita:

בארבעה ועשרים בטבת תבנא לדיננא שהיו צדוקין אומרין תירש הבת עם בת הבן נטפל להן רבן יוחנן בן זכאי אמר להם שוטים מנין זה לכם ולא היה אדם שהחזירו דבר חוץ מזקן אחד שהיה מפטפט כנגדו ואומר ומה בת בנו הבאה מכח בנו תירשנו בתו הבאה מכחו לא כל שכן

On the twenty-fourth of Tevet we returned to our judgments—for the Sadducees insisted that a daughter inherits [from her father] the same as a granddaughter inherits from her grandfather if her father is already dead. Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai took issue with them and said, “Fools, what are the grounds for this conclusion?” And there was not a man who could answer him a word in reply, except for one elder who was blathering [מפטפט] opposite him and saying, “If the granddaughter, who is related to the bestower of the inheritance only through the son, inherits, then the daughter, who is related directly to the bestower of the son, ought to inherit.” (b. Bab. Bat. 115b)

From the perspective of the rabbinic sages, the Sadducean elder’s answer was nothing more than rubbish because although his answer is logical, Jewish law is not derived from pure reason, it is based on Scripture. In his answer, the Sadducean elder either ignored or was ignorant of the plain teaching of Scripture that sisters do not inherit along with their brothers from their father. Only if a man dies with no male offspring do daughters inherit their father’s property.[18] The case of the granddaughter who does inherit if her father dies before her grandfather, which the Sadducean elder cited, is not a valid analogy, since the granddaughter merely inherits her grandfather’s property on her deceased father’s behalf. In that way, the son, though dead, is secured an equal share along with his living brothers. In the view of the rabbinic sages, the granddaughter who inherits is the exception that proves the rule, and they regarded the Sadducean elder as a blathering fool for not having recognized this.

We find the same rabbinic estimation of a Sadducean argument in another dispute between Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai and a Boethusian (i.e., Sadducean) elder:

מתמניא ביה ועד סוף מועדא איתותב חגא דשבועיא דלא למספד שהיו בייתוסין אומרים עצרת אחר השבת ניטפל להם רבן יוחנן בן זכאי ואמר להם שוטים מנין לכם ולא היה אדם אחד שהיה משיבו חוץ מזקן אחד שהיה מפטפט כנגדו ואמר משה רבינו אוהב ישראל היה ויודע שעצרת יום אחד הוא עמד ותקנה אחר שבת כדי שיהו ישראל מתענגין שני ימים

From the eighth thereof [i.e., of the month of Nisan] until the end of the Feast [of Unleavened Bread], during which the proper date of the Feast of Pentecost was reestablished, fasting is forbidden—For the Boethusians insisted Pentecost must fall on the day after the Sabbath [i.e., on a Sunday]. Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai took issue with them and said, “Fools, what are the grounds for this conclusion?” And there was not a man who could answer him a word in reply, except for one elder who was blathering [מפטפט] opposite him and saying, “Moses, our teacher, was a friend of Israel, and knowing that Pentecost was but a single day, he rose and ordained that it would fall after the Sabbath so that Israel would enjoy two days of rest.” (b. Men. 65a)

Here again, the Sadducean interlocutor used a non-Scriptural and (from the rabbinic point of view) invalid argument in support of his position.[19] The rabbinic sages regarded the elder’s speech as balderdash. While not necessarily devoid of meaning or logic, the elder’s speech was wrongheaded and therefore the object of the sages’ contempt.

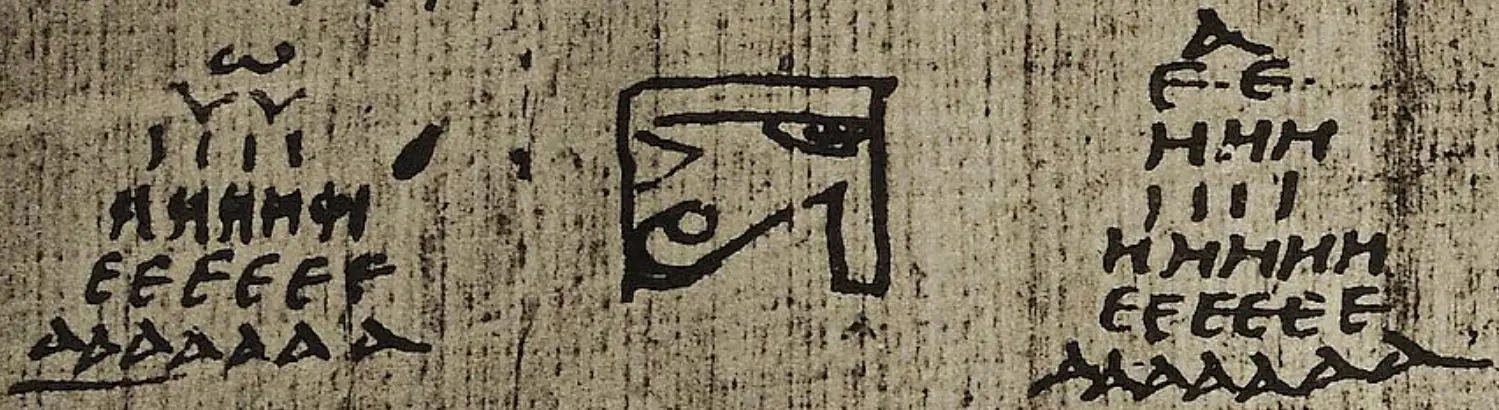

We cannot be certain what, in Jesus’ opinion, qualified the Gentiles’ prayers as blathering. In ancient magical Greek papyri from Egypt we encounter the use of meaningless vocalizations, such as the following, while addressing the gods:

ααααααα εεεεεεε ηηηηηηη ιιιιιιι οοοοοοο υυυυυυυ ωωωωωωω

aaaaaaa eeeeeee ēēēēēēē iiiiiii ooooooo ūūūūūūū ōōōōōōō (PGM II. 97)[20]

The magical papyri also contain lengthy repetitions of magical words, wherein the first letter of the word is dropped with each repetition until the speaker is reduced to silence, for example:

[ακρακαναρβα] κρακαναρβα ρακαναρβα ακαναρβα καναρβα αναρβα [ν]αρβα αρβα ρβα [βα] α

[akrakanarba] krakanarba rakanarba akanarba kanarba anarba [n]arba arba rba [ba] a (PGM II. 66-68; cf. PGM XXXIII. 1-20; PGM XXXIX. 1-20)

Another magical formula for addressing the gods was the use of palindromes, nonsense words that mirrored themselves, for instance:

αεμιναεβαρωθερρεθωραβεανιμεα

aeminaebarōtherrethōrabeanimea (PGM IV. 196-197; cf. PGM I. 295)

Fourth-century C.E. magical papyrus with incantation (PGM V. 85). From Karl Preisendanz, ed., Papyri Graecae Magicae (2 vols.; Leipzig: Teubner, 1928-1931), vol. 1 plate 3.

Any or all of these practices could be the target of Jesus’ critique of Gentile prayer, but since it is doubtful whether Jesus or his disciples had anything more than a vague impression of what non-Jews said or did when they prayed, it is unwise to be too specific.[21] Jesus may have regarded all Gentile prayer as blathering nonsense on the grounds that their prayers were not addressed to the God of Israel, whom he regarded as the only true God. At any rate, the more effort Gentiles put into their prayers, the more tragically futile their effort must have seemed to Jesus and his followers.

L3 ὥσπερ οἱ ὑποκριταί (Matt. 6:7; Vaticanus). As we noted under the “Story Placement” subheading, one of the clues that Praying Like Gentiles did not originally belong to Jesus’ critique of almsgiving, prayer and fasting as practiced by Jewish “hypocrites” (Matt. 6:2, 5, 16) is that in Praying Like Gentiles Jesus criticized the practice of non-Jews. The scribe who produced Codex Vaticanus attempted to integrate the Praying Like Gentiles pericope more fully into its Matthean context in the Sermon on the Mount by changing οἱ ἐθνικοί (“the Gentiles”) to οἱ ὑποκριταί (“the hypocrites”).[22] There can be little doubt that this reading in Codex Vaticanus is secondary, since it is inconceivable that a statement originally directed against Jews would have been turned into a criticism of Gentiles in the majority of NT manuscripts.[23]

Byzantine mosaic depicting Tyche, goddess of good fortune, crowned with the city walls of Scythopolis (Bet Shean), and holding a cornucopia. Photographed by Joshua Tilton at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

Changing “Gentiles” to “hypocrites” was more than an attempt to assimilate Praying Like Gentiles to its surrounding context, however. The change was also an attempt to avoid offending the Gentile-Christian readers for whom Codex Vaticanus was created.[24] But in making this change, the scribe who produced Codex Vaticanus turned the meaning of Jesus’ saying in Matt. 6:7 on its head. Instead of affirming Jewish forms of prayer, as Jesus had originally intended, the scribe who produced Codex Vaticanus transformed Matt. 6:7 into yet one more piece of ammunition in the Church’s anti-Jewish arsenal.[25] As such, the scribal change from “Gentiles” to “hypocrites” in Matt. 6:7 is a chilling premonition of the radical efforts to de-Judaize the New Testament that were to take place under the auspices of the Institut zur Erforschung und Beseitigung des jüdischen Einflusses auf das deutsche kirchliche Leben (Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life) in Nazi Germany.[26] The edition of the New Testament that this institute produced contained the notorious substitution of Jesus’ affirmation that “salvation is from the Jews” (John 4:22) with the anti-Semitic slogan “the Jews are our misfortune.”[27] In Vaticanus’ version of Matt. 6:7 we witness the perverse trajectory of anti-Jewish tampering with the text of the New Testament, which reached its apex in the work of the Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life, at a point much closer to its inauspicious beginning.

ὥσπερ οἱ ἐθνικοί (GR). For GR we have adopted ὥσπερ οἱ ἐθνικοί (hōsper hoi ethnikoi, “like the Gentiles”), the reading of the critical editions. The adjective ἐθνικός (ethnikos, “ethnic”), which is used in Matt. 6:7 as a substantive, does not occur in LXX, where, however, the noun ἔθνος (ethnos, “people group,”) occurs over 990xx. The adjective ἐθνικός is also rare in the writings of Philo (Mos. 1:69, 188) and Josephus (Ant. 12:36) and, indeed, in NT (Matt. 5:47; 6:7; 18:17; 3 John 7). The Matthean instances of ἐθνικός, at least in Matt. 5:47 and Matt. 6:7, probably derive from Anth.

In Classical Greek sources τὰ ἔθνη (ta ethnē, “the people groups”) was sometimes used in opposition to οἱ Ἕλληνες (hoi Hellēnes, “the Greeks”), with the clear implication that τὰ ἔθνη refers to outsider people groups (i.e., foreigners).[28] Similarly, the adjective ἐθνικός can mean “foreign.”[29] In LXX and in NT ἔθνος often conveys the sense of “foreigner,” but since the perspective in these sources is Jewish, the foreigners denoted by ἔθνος, and likewise ἐθνικός, are non-Jews (i.e., Gentiles).[30]

Statue of the goddess Artemis from the second century C.E., discovered in Caesarea. Photographed by Gary Asperschlager at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

In our discussion and translations we have preferred to use the term “Gentile” as opposed to “pagan” (e.g., NIV, GNT) or “heathen” (e.g., NEB, NKJV), which are used in some modern translations. “Heathen” we have avoided because in English usage this term tends to connote “primitive” and “uncivilized,” whereas τὰ ἔθνη/הַגּוֹיִם often refers to Greeks and Romans, the bearers of high culture in the ancient Mediterranean world. Our reason for avoiding “pagan” is that it is generally regarded as equivalent to “polytheist,” and therefore has the potential to give the misleading impression that Jesus might have exempted from his criticism enlightened non-Jews who adhered to a philosophical monotheism. It is questionable whether Jesus acknowledged the existence of such a category of persons, or whether they would have escaped his criticism if he had. “Gentile” is preferable, since according to Jesus’ worldview humanity was divided between Israel and the rest of the peoples of the world.[31] In Praying Like Gentiles Jesus indiscriminately critiqued all non-Jewish forms of prayer.

כַּגּוֹיִם (HR). In a survey of all the instances of ὥσπερ (hōsper, “as,” “like”) in the first five books of Moses, most were the translation of the preposition -כְּ (ke–, “like”).[32] As we noted above, ἐθνικός does not occur in LXX, but the related ἔθνος translates גּוֹי (gōy, “people group”) more than any other Hebrew noun,[33] and גּוֹי was rendered with ἔθνος far more frequently than with any other Greek term.[34]

In LXX כַּגּוֹיִם (kagōyim, “like the Gentiles”) is translated as καθὰ καὶ τὰ λοιπὰ ἔθνη (katha kai ta loipa ethnē, “as also the remaining people groups”) in Deut. 8:20, καθὼς τὰ ἔθνη (kathōs ta ethnē, “just as the people groups”) in 4 Kgdms. 17:11, and as ὡς τὰ ἔθνη (hōs ta ethnē, “as the people groups”) in Ezek. 20:32. If ὥσπερ οἱ ἐθνικοί in Matt. 6:7 does indeed reflect כַּגּוֹיִם in a Hebrew Ur-text, then it is a non-Septuagintal rendition of this phrase.

L4 שֶׁהֶם סְבוּרִים (HR). The verb δοκεῖν (dokein, “to think,” “to seem”) does not have a clear Hebrew equivalent in LXX. Often δοκεῖν appears where there is no Hebrew equivalent;[35] other times δοκεῖν renders אִם טוֹב (’im tōv, “if it is good”; Esth. 1:19; 3:9; 5:4; 8:5) or אָמַר (’āmar, “say”; Prov. 28:24). On the two occasions when δοκεῖν translates a Hebrew verb for “think,” that verb is either חָשַׁב (ḥāshav) or the nif ‘al form of the same root, נֶחְשַׁב (neḥshav):

וַיִּרְאֶהָ יְהוּדָה וַיַּחְשְׁבֶהָ לְזוֹנָה

And Judah saw her and thought she was a prostitute…. (Gen. 38:15)

καὶ ἰδὼν αὐτὴν Ιουδας ἔδοξεν αὐτὴν πόρνην εἶναι

And seeing her, Judas thought she was a prostitute…. (Gen. 38:15)

מְבָרֵךְ רֵעֵהוּ בְּקוֹל גָּדוֹל בַּבֹּקֶר הַשְׁכֵּים קְלָלָה תֵּחָשֶׁב לוֹ

Of the one who blesses his friend in a loud voice when rising early in the morning, it will be thought of as a curse. (Prov. 27:14)

ὃς ἂν εὐλογῇ φίλον τὸ πρωὶ μεγάλῃ τῇ φωνῇ, καταρωμένου οὐδὲν διαφέρειν δόξεἰ

Whoever blesses a friend early in the morning with a loud voice will seem not to be different from one who is cursing. (Prov. 27:14; NETS)

The LXX translators rendered חָשַׁב with a variety of Greek verbs.[36]

Although חָשַׁב is a viable option for HR, we have preferred to reconstruct δοκεῖν with סָבַר (sāvar, “think”), since Mishnaic Hebrew tended to use חָשַׁב for planning an action, whereas the passive participle סָבוּר (sāvūr) was used for holding an opinion, as we see in the following examples:[37]

הם סבורים לפני בשר ודם הם עומדים ואינם אלא לפני המקום

They think [הֵם סְבוּרִים] they are standing before flesh and blood [i.e., a mere mortal—DNB and JNT], but they are not. Rather [they are standing] before the Omnipresent one! (Sifre Deut. §190 [ed. Finkelstein, 230])

מה הם סבורים ששכחתי מה שעשו

What do they think [הֵם סְבוּרִים]? That I forgot what they did? (Midrash Tehillim 149:6 [ed. Buber, 541])

L5 שֶׁבְּרֹב דִּבְרֵיהֶם (HR). On reconstructing ὅτι (hoti, “that,” “because”) with -שֶׁ (she-, “that,” “because”), see Lost Sheep and Lost Coin, Comment to L31.

The noun πολυλογία (polūlogia, “loquaciousness,” “verbosity”) occurs once in LXX, where it is the translation of רֹב דְּבָרִים (rov devārim, “abundance of words”):

בְּרֹב דְּבָרִים לֹא יֶחְדַּל פָּשַׁע וְחֹשֵׂךְ שְׂפָתָיו מַשְׂכִּיל

In abundance of words sin will not cease, but the one who restrains his lips is wise. (Prov. 10:19)

ἐκ πολυλογίας οὐκ ἐκφεύξῃ ἁμαρτίαν, φειδόμενος δὲ χειλέων νοήμων ἔσῃ.

From many words you will not escape sin, but if you restrain your lips, you will be intelligent. (Prov. 10:19; NETS)

Elsewhere in LXX the phrase רֹב דְּבָרִים is translated as πολλὰ λέγων (polla legōn, “speaking much”; Job 11:2) or πλήθει λόγων (plēthei logōn, “copious speaking”; Eccl 5:2). Excluding biblical quotations, we have not found examples of רֹב דְּבָרִים in rabbinic sources. However, there is one example of this phrase in the Apocryphon of Joshua, discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls:

על [ע]וזבי אל וברב ד[ב]רי[ך — ]

…upon those who [for]sake God and by [your] many w[o]rds…. (4Q379 18 I, 2)

The text is too fragmentary to shed much light on the usage of רֹב דְּבָרִים in this example other than to demonstrate that this phrase could still be used by Hebrew authors in the Second Temple period.

L6 εἰσακουσθήσονται (GR). Although the presence of compound verbs is sometimes due to the editorial activity of the authors of Matthew, Mark, Luke or FR, some compound verbs probably derive from Anth. Since εἰσακούειν (eisakouein, “to listen to”) occurs over 200xx in LXX, usually as the translation of שָׁמַע (shāma‘, “hear,” “listen”),[38] this compound verb was probably familiar to the Greek translator of the conjectured Hebrew Life of Yeshua. Moreover, εἰσακούειν as the translation of שָׁמַע is particularly common in conjunction with prayer, as we see in the following examples:

לִשְׁמֹעַ אֶל הַתְּפִלָּה אֲשֶׁר יִתְפַּלֵּל עַבְדְּךָ אֶל הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה

…to listen to the prayer that your servant will pray toward this place. (1 Kgs. 8:29)

τοῦ εἰσακούειν τῆς προσευχῆς ἧς προσεύχεται ὁ δοῦλός σου εἰς τὸν τόπον τοῦτον

…to listen to the prayer that your servant prays toward this place…. (3 Kgdms. 8:29)

חָנֵּנִי וּשְׁמַע תְּפִלָּתִי

Be gracious to me and hear my prayer. (Ps. 4:2)

οἰκτίρησόν με καὶ εἰσάκουσον τῆς προσευχῆς μου

Have compassion on me and listen to my prayer. (Ps. 4:2)

שִׁמְעָה תְפִלָּתִי יי וְשַׁוְעָתִי הַאֲזִינָה

Hear my prayer, O LORD, and listen to my cry for help. (Ps. 39:13)

εἰσάκουσον τῆς προσευχῆς μου, κύριε, καὶ τῆς δεήσεώς μου ἐνώτισαι

Listen to my prayer, O Lord, and to my petition give ear. (Ps. 38:13; NETS)

אֱלֹהִים שְׁמַע תְּפִלָּתִי הַאֲזִינָה לְאִמְרֵי פִי

O God, hear my prayer; listen to the words of my mouth. (Ps. 54:4)

ὁ θεός, εἰσάκουσον τῆς προσευχῆς μου, ἐνώτισαι τὰ ῥήματα τοῦ στόματός μου

O God, listen to my prayer; give ear to the words of my mouth. (Ps. 53:4; NETS)

שֹׁמֵעַ תְּפִלָּה עָדֶיךָ כָּל בָּשָׂר יָבֹאוּ

Hearer of prayer: unto you all flesh will come. (Ps. 65:3)

εἰσάκουσον προσευχῆς μου· πρὸς σὲ πᾶσα σὰρξ ἥξεἰ

Listen to my prayer! To you all flesh shall come. (Ps. 64:3; NETS)

יי אֱלֹהִים צְבָאוֹת שִׁמְעָה תְפִלָּתִי הַאֲזִינָה אֱלֹהֵי יַעֲקֹב

O LORD God of Hosts, hear my prayer; listen, O God of Jacob. (Ps. 84:9)

κύριε ὁ θεὸς τῶν δυνάμεων, εἰσάκουσον τῆς προσευχῆς μου ἐνώτισαι, ὁ θεὸς Ιακωβ

O Lord God of hosts, listen to my prayer; give ear, O God of Iakob! (Ps. 83:9; NETS)

יי שִׁמְעָה תְפִלָּתִי וְשַׁוְעָתִי אֵלֶיךָ תָבוֹא

Hear my prayer, O LORD, and let my cry for help come to you. (Ps. 102:2)

Εἰσάκουσον, κύριε, τῆς προσευχῆς μου, καὶ ἡ κραυγή μου πρὸς σὲ ἐλθάτὠ

O Lord, listen to my prayer, and let my cry come to you. (Ps. 101:2; NETS)

יי שְׁמַע תְּפִלָּתִי הַאֲזִינָה אֶל תַּחֲנוּנַי

O LORD, hear my prayer; listen to my petitions…. (Ps. 143:1)

Κύριε, εἰσάκουσον τῆς προσευχῆς μου, ἐνώτισαι τὴν δέησίν μου

O Lord, listen to my prayer; give ear to my petition…. (Ps. 142:1; NETS)

Jesus’ critique of Gentiles who vainly expect their prayers to be heard is comparable to that which is found in the Jewish prayer called Aleinu, which states:

עָלֵינוּ לְשַׁבֵּחַ לַאֲדוֹן הַכֹּל לָתֵת גְּדֻלָּה לְיוֹצֵר בְּרֵאשִׁית שֶׁלֹּא עָשָׂנוּ כְּגוֹיֵי הָאֲרָצוֹת וְלֹא שָׂמָנוּ כְּמִשְׁפְּחוֹת הָאֲדָמָה שֶׁלֹּא שָׂם חֶלְקֵנוּ כָּהֶם וְגוֹרָלֵנוּ כְּכָל הֲמוֹנָם שֶׁהֵם מִשְׁתַּחֲוִים לְהֶבֶל וָרִיק וּמִתְפַּלְּלִים אֶל אֵל לֹא יוֹשִׁיעַ וַאֲנַחְנוּ כֹּרעִים וּמִשְׁתַּחֲוִים וּמוֹדִים לִפְנֵי מֶלֶךְ מַלְכֵי הַמְּלָכִים הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא

It is incumbent upon us to praise the Lord of all things, to ascribe greatness to the craftsman of creation, for he did not make us like the Gentiles of the lands and he did not establish us like the families of the earth, for he did not establish our portion [to be] like them, nor our lot [to be] like all their multitude. For they prostrate themselves to vanity and nothingness, and they pray to a deity that does not save.[39] But we bow down and prostrate ourselves and give thanks before the king of kings, the Holy one, blessed be he.

A first-century B.C.E. relief of an ear from Thessalonica dedicated to the gods Serapis and Isis by a worshipper in order that his prayers might be heard. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

While it is difficult to date liturgical texts such as the Aleinu prayer, some scholars believe it originated in the Second Temple period.[40] Whether or not Jesus was familiar with an early form of this prayer, he was certainly familiar with the biblical verses to which Aleinu alludes. The reference to “vanity and nothingness” (הֶבֶל וָרִיק) alludes to Isa. 30:7, where the prophet warns the kingdom of Judah that relying on Egypt for political deliverance will end in disappointment. The prayers of Gentiles to a deity that cannot save alludes to Isa. 45:20:

הִקָּבְצוּ וָבֹאוּ הִתְנַגְּשׁוּ יַחְדָּו פְּלִיטֵי הַגּוֹיִם לֹא יָדְעוּ הַנֹּשְׂאִים אֶת עֵץ פִּסְלָם וּמִתְפַּלְלִים אֶל אֵל לֹא יוֹשִׁיעַ

Gather and come! Draw close together, O survivors of the Gentiles. They who carry about wooden images do not know, neither do they who pray to a deity that cannot save. (Isa. 45:20)

Comparison of Matt. 6:7-8 with scriptural verses and later Jewish prayer demonstrates that Jesus belonged to a tradition that looked askance at non-Jewish forms of worship. The hope was that when the God of Israel redeemed his people the Gentiles would witness his saving power and recognize him as the only true God.[41] Thus the redemption of Israel would result in the salvation of all humankind.

L7 μὴ οὖν ὁμοιωθῆτε αὐτοῖς (Matt. 6:8). The verb ὁμοιοῦν (homoioun) means “to make like” and is typically used when making a comparison (cf., e.g., Matt. 11:16 ∥ Luke 7:31). This is the usual meaning of ὁμοιοῦν in LXX as well, but in the story of Jacob’s daughter Dinah the verb ὁμοιοῦν is used to describe the adoption of foreign practices. In that story, Jacob’s sons consent to their sister Dinah’s marriage to a particular Canaanite on condition that all the male Canaanites of his hometown, Shechem, agree to be circumcised. Attempting to persuade his fellow Shechemites to agree to this condition, the Canaanite urges:

μόνον ἐν τούτῳ ὁμοιωθήσονται ἡμῖν οἱ ἄνθρωποι τοῦ κατοικεῖν μεθ᾿ ἡμῶν ὥστε εἶναι λαὸν ἕνα, ἐν τῷ περιτέμνεσθαι ἡμῶν πᾶν ἀρσενικόν, καθὰ καὶ αὐτοὶ περιτέτμηνται. καὶ τὰ κτήνη αὐτῶν καὶ τὰ ὑπάρχοντα αὐτῶν καὶ τὰ τετράποδα οὐχ ἡμῶν ἔσται; μόνον ἐν τούτῳ ὁμοιωθῶμεν αὐτοῖς, καὶ οἰκήσουσιν μεθ᾿ ἡμῶν.

Only in this will the people become like [ὁμοιωθήσονται] us to live with us so as to be one people, when every male of ours is circumcised, as they also have been circumcised. And will not their livestock and their possessions and their quadrupeds be ours? Only in this let us become like [ὁμοιωθῶμεν] them, and they will live with us. (Gen. 34:22-23; NETS)

In the above passage the Canaanite urges his countrymen to become like the Israelites by adopting the foreign practice of circumcision in order that the Israelites may, in turn, be absorbed by the Shechemite community. Such a proposal was, of course, a direct threat to the unique relationship between God and the descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. To emphasize this threat the LXX translators used the verb ὁμοιοῦν (“to make like”; pass., “to become like”) to render the Hebrew root א-ו-ת (nif ‘al, “agree,” “be pleased”), which has a far less sinister connotation. In Praying Like Gentiles we encounter a similar concern to preserve the uniqueness of Israel’s relationship to God by avoiding the imitation of pagan rites and rituals.

אַל תִּהְיוּ כָּהֵם (HR). On omitting an equivalent to οὖν (oun, “therefore”) from HR despite the presence of οὖν in GR, see “The Harvest is Plentiful” and “A Flock Among Wolves,” Comment to L44.

In LXX ὁμοιοῦν (homoioun, “to make like”; pass., “to become like”) is usually the translation of דָּמָה (dāmāh, “be like”);[42] however, we do not find examples of commands against being like someone or something expressed with דָּמָה. Instead we find the formula -אַל תְּהִי כְּ (’al tehi ke-, “do not be like”), as in the following examples:

אַל תִּהְיוּ כַאֲבֹתֵיכֶם אֲשֶׁר קָרְאוּ אֲלֵיהֶם הַנְּבִיאִים הָרִאשֹׁנִים לֵאמֹר

Do not be like your fathers [LXX: μὴ γίνεσθε καθὼς οἱ πατέρες ὑμῶν], to whom the former prophets cried, saying…. (Zech. 1:4)

אַל תְּהִי מֶרִי כְּבֵית הַמֶּרִי

Do not be rebellious like the house of rebellion [LXX: μὴ γίνου παραπικραίνων καθὼς ὁ οἶκος ὁ παραπικραίνων]. (Ezek. 2:8)

אַל תִּהְיוּ כְּסוּס כְּפֶרֶד אֵין הָבִין

Do not be like a horse or like a mule [LXX: μὴ γίνεσθε ὡς ἵππος καὶ ἡμίονος], not understanding…. (Ps. 32:9)

וְאַל תִּהְיוּ כַּאֲבוֹתֵיכֶם וְכַאֲחֵיכֶם אֲשֶׁר מָעֲלוּ בַּיי אֱלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵיהֶם

And do not be like your fathers or like your brothers [LXX: καὶ μὴ γίνεσθε καθὼς οἱ πατέρες ὑμῶν καὶ οἱ ἀδελφοὶ ὑμῶν], who broke faith with the LORD, the God of your fathers…. (2 Chr. 30:7)

If our reconstruction of μὴ ὁμοιωθῆτε αὐτοῖς (mē homoiōthēte avtois, “do not be like them”) with אַל תִּהְיוּ כָּהֵם (’al tihyū kāhēm, “do not be like them”) is correct, then the Greek translator of the conjectured Hebrew Ur-text did not follow the model for rendering -אַל תְּהִי כְּ laid down by the LXX.

Examples of -אַל תְּהִי כְּ are also found in rabbinic sources, for instance:

אַנְטִיגְנַס אִישׁ סוֹכוֹ…הָיָה אוֹמֵ′ אַל תִּהְיוּ כַעֲבָדִים הַמְשַׁמְּשִׁים אֶת הָרָב עַל מְנַת לְקַבֵּל פְּרַס

Antigonos of Socho…would say, “Do not be like slaves [אַל תִּהְיוּ כַעֲבָדִים] who serve their master for the sake of receiving a reward….” (m. Avot 1:3)

לא תרצח כנגד ויאמר אלהים ישרצו המים אמר הקב″ה אל תהיו כדגים הללו שהגדולים בולעים את הקטנים שנאמר ותעשה אדם כדגי הים וגו′

Do not murder [Exod. 20:13] corresponds to And God said, “Let the waters team…” [Gen. 1:20]. The Holy one, blessed be he, said, “Do not be like these fish [אל תהיו כדגים הללו], for the big ones swallow the little ones, as it is said, And you made man like a fish of the sea [Hab. 1:14]. (Pesikta Rabbati 21:19 [ed. Friedmann, 108a])[43]

Statue of the goddess Kore (Persephone) from the second to fourth century C.E. discovered in Samaria. In her right hand Kore holds a torch, in her left she holds a pomegranate and ears of grain. Photo by Todd Bolen courtesy of BiblePlaces.com.

כָּהֵם (HR). In MH, when the third person plural pronominal suffix was attached to the preposition -כְּ (ke-, “like”), this was expressed as כְּמוֹתָם (kemōtām, “like them”), whereas in BH -כְּ + third person plural pronominal suffix took the form כָּהֵם (kāhēm, “like them”).[44] Although we prefer to reconstruct direct speech in a Mishnaic style of Hebrew, we have preferred the older form כָּהֵם in this case, first because the form כְּמוֹתָם did not become common until post-tannaic sources,[45] and second because it appears that the older form כָּהֵם continued to be used even after the use of כְּמוֹתָם was accepted.

The following is an example of כָּהֵם in a rabbinic source:

יש גר כאברהם אבינו כאי זה צד הלך ופישפש בכל האומות כיון שראה שמספרין בטובתן של ישראל אמר מתי אתגייר [ואהיה כהם] ואכנס תחת כנפי השכינה

There is a proselyte like Abraham our father. How so? He went and made inquiries among all the Gentiles. As soon as he saw that they reported the goodness of Israel, he said, “When will I convert [so that I can be like them (ואהיה כהם)] and so that I can enter beneath the wings of the Shechinah?” (Seder Eliyahu Rabbah, chpt. [29] 27 [ed. Friedmann, 146])

We also encounter the form כָּהֶם in a line from Aleinu (cited above, Comment to L6):

שֶׁלֹּא שָׂם חֶלְקֵנוּ כָּהֶם וְגוֹרָלֵנוּ כְּכָל הֲמוֹנָם

…for he did not establish our portion [to be] like them [כָּהֶם] [i.e., the Gentiles—DNB and JNT], nor our lot [to be] like all their multitude.

In the last two examples “being like others” refers specifically to Jewish-Gentile relations. In the first instance a model proselyte desires to become like Israel by converting to Judaism. In the second example Israelites give thanks that they are not like Gentiles who practice empty religions. These examples hark back to our discussion of the use of ὁμοιοῦν (homoioun, “to make like”) in the story of Jacob’s daughter Dinah (Gen. 34), which in turn confirms our impression that in Matt. 6:7-8 Jesus warned his disciples against the dangers of assimilation. According to the author of 2 Kings, assimilation was the reason the northern tribes were sent into exile:

וַיִּמְאֲסוּ אֶת חֻקָּיו וְאֶת בְּרִיתוֹ אֲשֶׁר כָּרַת אֶת אֲבוֹתָם וְאֵת עֵדְוֹתָיו אֲשֶׁר הֵעִיד בָּם וַיֵּלְכוּ אַחֲרֵי הַהֶבֶל וַיֶּהְבָּלוּ וְאַחֲרֵי הַגּוֹיִם אֲשֶׁר סְבִיבֹתָם אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יי אֹתָם לְבִלְתִּי עֲשׂוֹת כָּהֶם

And they rejected his statutes and his covenant, which he made with their fathers, and his testimonies, which testified against them, and they walked after false vanities and after the Gentiles who were around them, whom the LORD commanded them not to behave like them [כָּהֶם]. (2 Kgs. 17:15)

The prophet Ezekiel, on the other hand, worried that exile would increase the likelihood that Israel would disappear into the cultures of the peoples among whom they lived. Accordingly, he warned:

וְהָעֹלָה עַל רוּחֲכֶם הָיוֹ לֹא תִהְיֶה אֲשֶׁר אַתֶּם אֹמְרִים נִהְיֶה כַגּוֹיִם כְּמִשְׁפְּחוֹת הָאֲרָצוֹת לְשָׁרֵת עֵץ וָאָבֶן

The idea that has surfaced in your mind will certainly never be—what you are saying: “We will be like the Gentiles and like the families of the earth by worshipping wood and stone.” (Ezek. 20:32)

This Ezekiel passage can be compared to the following warning in the Temple Scroll:

ולוא תעשו כאשר הגויים עושים

And you must not do as the Gentiles are doing…. (11QTa [11Q19] XLVIII, 11)

Partial or complete assimilation of Jews to the dominant Greco-Roman culture was a reality in the first century C.E.[46] Perhaps the most famous example of Jewish assimilation in the ancient world is that of Tiberias Julius Alexander, the nephew of the first-century Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria. Tiberias Alexander not only renounced his ancestral religion (Jos., Ant. 20:100), but as a general in the Roman army he directed the siege of Jerusalem under Titus that ended with the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E. (Jos., J.W. 5:45-46; 6:237).[47]

L8 οἶδεν γὰρ ὁ πατὴρ ὑμῶν (GR). Codex Vaticanus and a few other ancient witnesses add ὁ θεός (hō theos, “the God”) before ὁ πατὴρ ὑμῶν (ho patēr hūmōn, “the father of you”).[48] That ὁ θεός should be omitted is supported from the textual evidence and also from the parallel in Matt. 6:32 ∥ Luke 12:30.[49]

כִּי יָדַע אֲבִיכֶם (HR). On reconstructing εἰδεῖν (eidein, “to know”) with יָדַע (yāda‘, “know”), see Rich Man Declines the Kingdom of Heaven, Comment to L20. In LXX we find that εἰδεῖν + γάρ is almost always the translation of יָדַע + כִּי.[50] Although other reconstructions are possible (e.g., הֲרֵי יוֹדֵעַ אֲבִיכֶם [“Behold, your father knows”]), we have allowed the LXX examples to guide our reconstruction.

On reconstructing πατήρ (patēr, “father”) with אָב (’āv, “father”), see Demands of Discipleship, Comment to L10.

Detail of the third-century C.E. mosaic from the Dionysus house in Tzippori (Sepphoris). Photographed by Joshua N. Tilton.

Notice that instead of criticizing the gods of the Gentiles as impotent or unreal, or characterizing them as demons, Jesus directs the disciples’ attention to the character of Israel’s God. The God of Israel is a father to his people, and as such he intimately knows both them and their needs. There was a tendency, especially in Diaspora Judaism, to avoid direct criticism of the Gentiles’ gods.[51] Whereas pagan practices were polemicized against, it was considered too incendiary to impugn the gods themselves. Perhaps Jesus’ redirection of the disciples’ attention to the character of their heavenly father was an expression of this sensitivity.

L9 אֵי זֶה צוֹרֶךְ יֵשׁ לָכֶם (HR). On the use of אֵי זֶה (’ē zeh, “which”) as a demonstrative, see Sending the Twelve: Conduct in Town, Comment to L80. As Segal noted, “In the older texts…the…components [אֵי and זֶה—DNB and JNT] are still kept separate.”[52]

Compare our reconstruction of χρείαν ἔχετε (chreian echete, “need you have”) as צוֹרֶךְ יֵשׁ לָכֶם (tzōrech yēsh lāchem, “need there is to you”) to our reconstruction of the statement οὐ χρείαν ἔχουσιν οἱ ὑγιαίνοντες ἰατροῦ (“not a need the healthy have of a doctor”) as אֵין צוֹרֶךְ לַבְּרִיאִים בְּרוֹפֵא (“there is no need to the healthy for a doctor”) in Call of Levi, L59-60.

On reconstructing ἔχειν (echein, “to have”) with יֵשׁ (yēsh, “there is”), see Tower Builder and King Going to War, Comment to L4.

L10 לִפְנֵי שֶׁאַתֶּם שׁוֹאֲלִים מִמֶּנּוּ (HR). In LXX πρὸ τοῦ + infinitive usually translates the construction טֶרֶם + finite verb (often with the preposition -בְּ prefixed to טֶרֶם).[53] However, the adverb טֶרֶם (ṭerem, “before,” “not yet”) disappeared in MH and was replaced with constructions such as -לִפְנֵי שֶׁ (lifnē she-, “before that”) or -קוֹדֶם שֶׁ (qōdem she-, “before that”).[54] Since we prefer to use a Mishnaic style of Hebrew to reconstruct direct speech, we have adopted the -לִפְנֵי שֶׁ construction for HR.

A first-century C.E. fresco from Pompeii depicting a Gentile sacrifice. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

On reconstructing αἰτεῖν (aitein, “to ask”) as שָׁאַל (shā’al, “ask”), see Friend in Need, Comment to L22. In HR we have supplied the preposition מִמֶּנּוּ (mimenū, “from him”), even though Matt. 6:8 lacks a preposition such as παρά (para, “from”) before the personal pronoun, because שָׁאַל אֵת typically means “inquire,” whereas שָׁאַל מִן means “request.”[55] In rare instances LXX omits a preposition where MT has שָׁאַל מִן,[56] and we suspect this may have happened when Praying Like Gentiles was translated from Hebrew to Greek. Compare our reconstruction of αἰτεῖν + personal pronoun with שָׁאַל מִן in Fathers Give Good Gifts, L20.

The notion that God knows a person’s prayer before it is spoken is also found in rabbinic sources, for instance:

אָמַר רַ′ אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן פְּדָת בָּשָׂר וָדָם אִם שׁוֹמֵעַ דִּבְרֵי אָדָם עוֹשֶׂה דִּינוֹ, אִם לֹא שָׂמַע אֵינוֹ יָכוֹל לְכַוֵּן דִּינוֹ, אֲבָל הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא אֵינוֹ כֵן, עַד שֶׁלֹּא יְדַבֵּר אָדָם הוּא יוֹדֵעַ מַה בְּלִבּוֹ…עַד שֶׁלֹּא יְצָרָהּ מַחֲשָׁבָה שֶׁבְּלִבּוֹ שֶׁל אָדָם, הוּא מֵבִין

Rabbi Eleazar ben Pedat said, “If a creature of flesh and blood hears a person’s speech he does as the speaker intended, but if he did not hear he is not able to understand his intention, but with the Holy one, blessed be he, it is not so. Before a person speaks he knows what is in his heart…before a thought is formed in a person’s heart he understands.” (Exod. Rab. 21:3 [ed. Merkin, 5:246-247])

Redaction Analysis[57]

| Praying Like Gentiles | |||

| Matthew | Anthology | ||

| Total Words: |

34 | Total Words: |

32 |

| Total Words Identical to Anth.: |

31 | Total Words Taken Over in Matt.: |

31 |

| % Identical to Anth.: |

91.18 | % of Anth. in Matt.: |

96.88 |

| Click here for details. | |||

The author of Matthew faithfully copied the Praying Like Gentiles pericope from Anth. without making any discernible changes to its wording.[58] While the Anthologizer (the creator of Anth.) was probably responsible for divorcing Praying Like Gentiles from its original context,[59] it was the author of Matthew who inserted this pericope into its current position in the Sermon on the Mount.[60]

Results of This Research

1. In light of the Praying Like Gentiles pericope, how should we characterize Jesus’ view of non-Jews? From Praying Like Gentiles we learn that Jesus did not have a high opinion of non-Jewish religious practices. As far as he was concerned, their worship was misdirected because they were unenlightened by God’s revelation in the Torah. Consequently, Gentiles did not know to whom they prayed or how their prayers ought to be formulated. Had they been enlightened by the Torah, the Gentiles would have understood that their ancestral deities are not true gods, and that the one true God is the LORD God of Israel, who is the father of all humankind. Knowing him as father, the Gentiles would have understood that prayers do not need to cajole or persuade or coerce God. Because God relates to human beings as a father to his children, Jesus’ followers could (and can) pray with assurance that God hears and knows how to provide for their needs.

Despite his dim view of non-Jewish religious practices, it is clear from his limited interactions with non-Jews that Jesus did not regard Gentiles as irredeemable.[61] If Gentiles renounced their idols and false gods and turned in hope to the God of Israel, then they too could be saved from the power of Satan and participate in the blessings of the renewal of creation through the Kingdom of Heaven.

2. How should Jesus’ view of non-Jewish religious practices inform our view of Judaism? This is a question that is rarely asked of the Praying Like Gentiles pericope. As we have seen, there has been a tendency among Christian interpreters to turn Jesus’ critique of Gentile religious practices into an attack against Jewish prayer in particular and against Judaism in general. A sensitive reading of Matt. 6:7-8 reveals that Jesus affirmed Jewish modes of prayer by urging his disciples not to adopt Gentile prayer habits. The clear implication was that Jesus wanted his disciples to remain true to their Jewish heritage and to pray on the basis of the covenant relationship God had established with Israel through the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

Conclusion

In Praying Like Gentiles Jesus emphasized God’s unique relationship to Israel in order to reassure his disciples that God knew their needs and would faithfully provide for them. These themes are picked up and elaborated upon in the pericopae that follow in the conjectured “How to Pray” complex.

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Click here to return to The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction main page.

_______________________________________________________

Notes

- For abbreviations and bibliographical references, see “Introduction to ‘The Life of Yeshua: A Suggested Reconstruction.’” ↩

- This translation is a dynamic rendition of our reconstruction of the conjectured Hebrew source that stands behind the Greek of the Synoptic Gospels. It is not a translation of the Greek text of a canonical source. ↩

- See Allen, Matt., 57; Bundy, 111; Knox, 2:25-26; Beare, Earliest, 61 §§28-31; Nolland, Matt., 283. ↩

- Catchpole presented one of the clearest arguments that Matt. 6:7-8 is an independent unit in David R. Catchpole, “Q and ‘The Friend at Midnight’ (Luke XI.5-8/9),” Journal of Theological Studies 34.2 (1983): 407-424, esp. 422. ↩

- Note that “seeking” is a metaphor for prayer in the Friend in Need simile (L24, L27; Matt. 7:7-8 ∥ Luke 11:9-10). ↩

- Cf. Catchpole, “Q and ‘The Friend at Midnight’ (Luke XI.5-8/9),” 422-423; Luz, 1:305. ↩

- On the mainly non-Jewish constituency of the Matthean community, which nevertheless regarded itself as the “true Israel” and the only faithful adherents to the Torah (as interpreted by the Matthean community), see David Flusser, “Matthew’s ‘Verus Israel’” (Flusser, JOC, 561-574). Matthew’s vision of the Church is contrary to Paul’s, according to which Jewish and Gentile believers should co-exist within the same community while maintaining their differences and respecting one another’s differing ways of life. On Paul’s vision for the Church, see Peter J. Tomson, “Paul’s Jewish Background in View of His Law Teaching in 1Cor 7,” in Paul and the Mosaic Law (ed. James D. G. Dunn; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 251-270; Paula Fredriksen, “Judaizing the Nations: The Ritual Demands of Paul’s Gospel,” New Testament Studies 56 (2010): 232-252; idem, “Why Should a ‘Law-Free’ Mission Mean a ‘Law-Free’ Apostle?” Journal of Biblical Literature 134.3 (2015): 637-650.

Matthew’s anti-Pauline vision has been recognized by David C. Sim, “Matthew’s anti-Paulinism: A neglected feature of Matthean studies,” HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 58.2 (2002): 767-783; idem, “Matthew 7.21-23: Further Evidence of its Anti-Pauline Perspective,” New Testament Studies 53.3 (2007): 325-343; idem, “Matthew, Paul and the origin and nature of the gentile mission: The great commission in Matthew 28:16-20 as an anti-Pauline tradition,” HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 64.1 (2008): 377-392.

The Didache, a source that likely emerged from the greater Matthean community, also encouraged Gentile believers to strive toward perfect observance of the Torah (Did. 6:2-3). See David Flusser, “Paul’s Jewish Christian Opponents in the Didache,” in Gilgul: Essays on Transformation, Revolution and Permanence in the History of Religions (ed. Shaul Shaked, David Schulman, and Guy G. Stroumsa; Leiden: Brill, 1987), 71-90. On the close connections between the Didache and the Gospel of Matthew, see Huub van de Sandt, “The Didache and its Relevance for Understanding the Gospel of Matthew.” ↩

- See Davies-Allison, 1:587. ↩

- Text according to Antonius Westermann, ed., Vita Aesopi (London: Williams and Norgate, 1845). Translation according to Betz, 364 n. 269. ↩

- Translation according to Montefiore, TSG, 2:99. ↩

- See Allen, Matt., 57; McNeile, 76; Montefiore, TSG, 2:99; Frederick Bussby, “A Note on ῥακά (Matthew V.22) and βατταλογέω (Matthew VI.7) in the Light of Qumran,” Expository Times 76.1 (1964): 26; Davies-Allison, 1:587. ↩

- See Betz, 364-365; Nolland, Matt., 284 n. 306. ↩

- See John Ernest Leonard Oulton and Henry Chadwick, eds. and trans., Alexandrian Christianity: Selected Translations of Clement and Origen (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1954), 181. ↩

- Text according to Paul Koetschau et al., eds., Origenes Werke (12 vols.; Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1899-1941). Translation according to Oulton and Chadwick, Alexandrian Christianity, 279. On the possible influence of rabbinic thought and practice on Origen’s treatise on prayer, see Marc Hirshman, “A Protocol for Prayer: Origen, the Rabbis and their Greco-Roman Milieu,” in Essays on Hebrew Literature in Honor of Avraham Holtz (ed. Z. Ben-Yosef Ginor; New York: Jewish Theological Seminary, 2003), 3-14. ↩

- Translation according to Oulton and Chadwick, Alexandrian Christianity, 298. ↩

- See Gerhard Delling, “βατταλογέω,” TDNT, 1:597. ↩

- Luz, 1:305 n. 3. ↩

- On the laws of inheritance pertaining to women in ancient Judaism, see Tal Ilan, Jewish Women in Greco-Roman Palestine (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1996), 167-170. ↩

- On the dispute between the Pharisees and the Sadducees over the correct dating of Pentecost (Shavuot), see Shmuel Safrai, “Counting the Omer: On What Day of the Week Did Jesus Celebrate Shavuot (Pentecost)?” ↩

- Karl Preisendanz et al., eds., Papyri Graecae Magicae. Die Griechischen Zauberpapyri (2 vols.; Stuttgart: Teubner, 1973-1974). ↩

- Since it is improbable that Jesus attended rites at Gentile temples or studied with Gentile priests or philosophers, it is likely that his knowledge of Gentile prayers and Gentile religion generally was at best secondhand. Jesus did not have an insider’s view, nor even a sympathetic outsider’s view, of non-Jewish religious practices, and therefore his characterization of Gentile prayers must be taken with a grain of salt. On Gentile religious practices as they were observed in the land of Israel during the time of Jesus, see David Flusser, “Paganism in Palestine” (Safrai-Stern, 2:1065-1100).

Pliny the Elder (first cent. C.E.) offered the following description of Roman prayer:

…[O]ur chief magistrates have adopted fixed formulas for their prayers; that to prevent a word’s being omitted or out of place a reader dictates beforehand the prayer from a script; that another attendant is appointed as a guard to keep watch, and yet another is put in charge to maintain a strict silence; that a piper plays so that nothing but the prayer is heard. (Nat. Hist. 28:3 §11; Loeb)

Fixed formulas for the Amidah, the central prayer in Jewish daily life, were established under the leadership of Rabban Gamliel II in the late first century C.E. See Shmuel Safrai, “Gathering in the Synagogues on Festivals, Sabbaths and Weekdays,” British Archaeological Reports (International Series) 449 (1989): 7-15, esp. 11; Peter J. Tomson, “The Halakhic Evidence of Didache 8 and Matthew 6 and the Didache Community’s Relationship to Judaism,” in Matthew and the Didache: Two Documents from the Same Jewish-Christian Milieu? (ed. Huub van de Sandt; Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005), 131-141, esp. 137-139; idem, “The Lord’s Prayer (Didache 8) at the Faultline of Judaism and Christianity,” in The Didache: A Missing Piece of the Puzzle in Early Christianity (ed. Jonathan Draper; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2015), 165-187, esp. 175-183.

On non-Jewish writers who exhorted their fellow Gentiles to maintain decorum in their prayers, see Betz, 365-367. For introductions to Greek and Roman prayer, see H. S. Versnel, “Religious Mentality in Ancient Prayer,” in Faith Hope and Worship: Aspects of Religious Mentality in the Ancient World (ed. H. S. Versnel; Leiden: Brill, 1981), 1-64; Larry J. Alderink and Luther H. Martin, “Prayer in Greco-Roman Religions,” in Prayer From Alexander to Constantine: A Critical Anthology (ed. Mark Kiley et al.; London: Routledge, 1997), 123-127. This volume contains a useful collection of translated Jewish, Greek, Roman and Christian prayers from the ancient world. ↩

- See Catchpole, “Q and ‘The Friend at Midnight’ (Luke XI.5-8/9),” 422; Nolland, Matt., 279; Tomson, “The Halakhic Evidence of Didache 8 and Matthew 6 and the Didache Community’s Relationship to Judaism,” 137. ↩

- Pace Black (133-134), who objected that there was “scarcely need for Jews to be exhorted not to pray as Gentiles,” and therefore concluded that ἐθνικοί (“Gentiles”) in Matt. 6:7 is a Jewish-Christian emendation of the original text. We do not find Black’s arguments to be convincing. In the first place, holding up Gentile behavior as a negative model for Jews to avoid is hardly unusual in ancient Jewish sources (cf., e.g., Lev. 18:24-27; Deut. 18:9; Jub. 22:16-18; Matt. 6:32 ∥ Luke 12:30). In the second place, if Jews did not need to be exhorted not to pray like Gentiles, then it would seem equally unnecessary for Jewish-Christians to exhort their coreligionists not to pray like Gentiles. For further objections to Black’s opinion, see Davies-Allison, 1:589 n. 23. ↩

- See Davies-Allison, 1:589; Hagner, 1:144; France, Matt., 240. ↩

- On the use of Matt. 6:7-8 by Christians in anti-Jewish polemics, see Abrahams, 2:102; Montefiore, RLGT, 119; Luz, 1:306. Even after the Holocaust, some scholars have not been able to resist bringing up Jewish modes of prayer in their discussions of Matt. 6:7-8. Cf. Jeremias (Theology, 192), who wrote: “Jesus censures the scribes οἱ…προφάσει μακρὰ προσευχόμενοι ([“who…make long pretentious prayers”—DNB and JNT] Mark 12.40): he reprimands them [sic] for βατταλογεῖν (Matt. 6.7).” ↩

- On the Institut zur Erforschung und Beseitigung des jüdischen Einflusses auf das deutsche kirchliche Leben, see Susannah Heschel, “Nazifying Christian Theology: Walter Grundmann and the Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Church Life,” Church History 63.4 (1994): 587-605. ↩

- See Heschel, “Nazifying Christian Theology,” 595. ↩

- See LSJ, 480; Karl Ludwig Schmidt, “ἔθνος in the NT,” TDNT, 2:369-371, esp. 370. ↩

- See LSJ, 480; Schmidt, “ἐθνικός,” TDNT, 2:372. ↩

- Runia notes that “The term ‘Gentile’ came into the English language via the Latin word gentes, commonly used in the Vulgate [i.e., the Latin translation of the Bible—DNB and JNT], and was greatly popularized in the King James Version, where in the New Testament it is even used to translate ‘Greeks’ (e.g., Rom. 3.9). It [i.e., ‘Gentile’—DNB and JNT] is primarily used to render the term goyim in the Hebrew Bible, which is translated τὰ ἔθνη in the Septuagint.” See David T. Runia, “Philo and the Gentiles,” in Attitudes to Gentiles in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity (ed. David C. Sim and James S. McLauren; London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 28-45, esp. 30. ↩

- For a discussion of the different nuances of the terms “gentile” and “pagan,” see Fredriksen, “Judaizing the Nations: The Ritual Demands of Paul’s Gospel,” 242 n. 23; idem, “Why Should a ‘Law-Free’ Mission Mean a ‘Law-Free’ Apostle?” 639. ↩

- In LXX (Gen.-Deut.) ὥσπερ is the translation of -כְּ in Gen. 38:11; Exod. 12:48; 21:7; 24:10; Lev. 4:26; 6:10 (2xx); 7:7; 14:35; 27:21; Num. 17:5; Deut. 2:10, 11, 21; 3:20; 5:14; 6:24; 7:26; 10:1; 11:10; 18:7, 18; 20:8; 29:22; 33:26. Tied in second place for the most common term translated by ὥσπερ in LXX (Gen.-Deut.) are כַּאֲשֶׁר (ka’asher, “just as,” “while”; Deut. 2:22; 3:2, 6) and הִנֵּה (hinēh, “look,” “behold”; Gen. 37:9; 41:18, 22). ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 1:368-373. On the equivalence of ἔθνος with גּוֹי in LXX, see Georg Bertram, “ἔθνος, ἐθνικός,” TDNT, 2:364-369. N.B.: Georg Bertram was director of the Institut zur Erforschung und Beseitigung des jüdischen Einflusses auf das deutsche kirchliche Leben from 1943 until its dissolution in May 1945. As early as December 1933 Bertram had joined the Nationalsozialistische Lehrerbund (National Socialist Teachers League). See Heschel, “Nazifying Christian Theology,” 595 n. 39. Bertram’s writings should be used with caution, since his interpretation of the facts may be colored by his anti-Semitic worldview. ↩

- See Dos Santos, 35. ↩

- There is no Hebrew term behind δοκεῖν in Job 1:21; 15:21; 20:7, 22; Prov. 2:10; 14:12; 16:25; 17:28; 26:12. ↩

- See Dos Santos, 71. ↩

- Other reconstruction options such as הָאֹמְרִים בִּלְבָבָם (hā’omrim bilvāvām, “who say in their heart”; Delitzsch) or שֶׁנִדְמֶה לָהֶם (shenidmeh lāhem, “because it appears to them”), expressed in the passive voice, are dissimilar to the Greek text. ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 1:408-410. ↩

- The sentence marked in red was banned from Jewish prayer books by Christian censors in Europe. On the history of censorship of this prayer, see Ruth Langer, “The Censorship of Aleinu in Ashkenaz and its Aftermath,” in The Experience of Jewish Liturgy: Studies Dedicated to Menahem Schmelzer (ed. Debra Reed Blank; Leiden: Brill, 2011), 147-166. ↩

- The Aleinu prayer is not cited or alluded to in tannaic or amoraic sources, and the earliest documents containing the text of Aleinu date to the tenth century C.E. See Jeffrey Hoffman, “The Image of The Other in Jewish Interpretations of Alenu,” Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations 10.1 (2015): 1-41, esp. 4. Nevertheless, since liturgy is a peripheral topic in rabbinic sources, it is possible that Aleinu originated at a much earlier date than that of its earliest witnesses. Moreover, according to Langer (“The Censorship of Aleinu in Ashkenaz and its Aftermath,” 148), “In literary style, it [i.e., the Aleinu prayer—DNB and JNT] is consistent with the earliest forms of rabbinic-era liturgical poetry from the land of Israel.” According to Weinfeld, “Most scholars today consider it [i.e., the Aleinu prayer—DNB and JNT] an ancient prayer, from the second temple period.” See Moshe Weinfeld, “The Day of the LORD: Aspirations for the Kingdom of God in the Bible and Jewish Liturgy,” in his Normative and Sectarian Judaism of the Second Temple Period (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 68-89, esp. 75. ↩

- On the Jewish eschatological hope that the Gentiles would turn to the God of Israel when the LORD redeemed his people, see Paula Fredriksen, “Judaism, the Circumcision of Gentiles, and Apocalyptic Hope: Another Look at Galatians 1 and 2,” Journal of Theological Studies 42.2 (1991): 532-564. ↩

- See Hatch-Redpath, 2:993. ↩

- The midrash from which this passage is taken demonstrates a correspondence between the Ten Commandments and the ten pronouncements by which the world was created according to the account in Genesis. ↩

- Examples of the form כָּהֵם are found in 2 Sam. 24:3 (2xx); 2 Kgs. 17:15; Eccl. 9:12; 1 Chr. 21:3; 2 Chr. 9:11. ↩

- We have found only three places in tannaic sources where the form כְּמוֹתָם occurs:

משל למה הדבר דומה למלך בשר ודם שנכנס למדינה ועליו צפירה מקיפתו וגבוריו מימינו ומשמאלו וחיילות מלפניו ומלאחריו והיו הכל שואלין איזה הוא המלך מפני שהוא בשר ודם כמותם אבל כשנגלה הקב″ה על הים לא נצרך אחד מהם לשאול איזהו המלך אלא כיון שראוהו הכירוהו ופתחו כלן ואמרו זה אלי ואנוהו

A parable: to what may the matter be compared? To a king of flesh and blood who enters a province and a circle of guards surround him, and his mighty men are to his right and his left, and soldiers are ahead of him and behind him, and everyone asks, “Which one is the king?” because he is flesh and blood like them [כמותם]. But when the Holy one, blessed be he, revealed himself at the Red Sea not one of them needed to ask, “Which one is the king?” Rather, as soon as they saw him they recognized him and everyone opened [their mouths] and said, This is my God and I will glorify him [Exod. 15:2]. (Mechilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Shirata chpt. 3 [ed. Lauterbach, 1:184-185])

מה ענבים בנזיר עשה מה שיוצא מהם כמותם אף בהמה נעשה את שיוצא מהם כמותם

Now grapes are forbidden to a Nazirite, and Scripture regards what comes out of them [i.e., the juice—DNB and JNT] to be like them [כמותם] [i.e., also forbidden to a Nazirite—DNB and JNT]. So also, in the case of an animal forbidden for consumption, should not what comes out of them [i.e., milk—DNB and JNT] be regarded like them [כמותם] [i.e., also forbidden—DNB and JNT]? (Sifra, Shmini perek 4 [ed. Weiss, 48d])

↩או כמעשה ארץ מצרים וכמעשה ארץ כנען לא תעשו יכול לא יבנו בניינות ולא יטעו נטיעות כמותם תלמוד לומר ובחוקותיהם לא תלכו

Or according to the deeds of the land of Egypt…and according to the deeds of the land of Canaan…you must not act [Lev. 18:3]. It is possible that this could be understood as “Do not build buildings or plant vegetation like them [כמותם],” therefore Scripture says, and in their statutes do not walk [Lev. 18:3]. (Sifra, Aḥare Mot parasha 9 [ed. Weiss, 85d])

- The apostle Paul (1 Cor. 7:18) mentioned the practice of Jews removing the marks of their circumcision in order to assimilate 1 Cor. 7:18. See Tomson, If This Be, 180-181. On assimilation and other Jewish responses to imperialism, see Joshua N. Tilton, “A Mile on the Road of Peace,” on WholeStones.org. ↩

- On Tiberias Julius Alexander, see Daniel R. Schwartz, “Philo, His Family, and his Times,” in The Cambridge Companion to Philo (ed. Adam Kamesar; Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 9-31. ↩

- See Metzger, 15. ↩

- See Yeshua’s Discourse on Worry, Comment to L53. ↩

- See Gen. 3:5 (ᾔδει γὰρ ὁ θεὸς = כִּי יֹדֵעַ אֱלֹהִים); 18:19 (ᾔδειν γὰρ = כִּי יְדַעְתִּיו); Exod. 3:7 (οἶδα γὰρ τὴν ὀδύνην αὐτῶν = כִּי יָדַעְתִּי אֶת מַכְאֹבָיו); Deut. 31:29 (οἶδα γὰρ = כִּי יָדַעְתִּי); Ruth 3:11 (οἶδεν γὰρ πᾶσα φυλὴ λαοῦ μου = כִּי יוֹדֵעַ כָּל־שַׁעַר עַמִּי); Job 23:10 (οἶδεν γὰρ = כִּי יָדַע); 30:23 (οἶδα γὰρ = כִּי יָדַעְתִּי). ↩

- In LXX the command “You must not curse God” (Exod. 22:27) was translated as “You must not disrespect the gods [of the Gentiles].” Such an interpretation had the dual function of tamping down the zealous impulses of the more volatile members of the Jewish community and demonstrating to non-Jews that Judaism was not an intolerant religion (cf. Philo, QE 2:5). See Pieter W. van der Horst, “‘Thou Shalt not Revile the Gods’: The LXX Translation of Ex. 22:28 (27), Its Background and Influence,” Studia Philonica Annual 5 (1993): 1-8. ↩

- Segal, 44 §80. ↩

- In LXX πρὸ τοῦ + infinitive translates the construction טֶרֶם + finite verb in Gen. 2:5 (2xx); 19:4; 24:15, 45; 37:18; 41:50; 45:28; Exod. 12:34; Deut. 31:21; Josh. 3:1; Ruth 3:14; Ps. 57[58]:10; Prov. 30:7; Zeph. 2:2 (2xx); Isa. 42:9; Jer. 13:16; Ezek. 16:57. ↩

- See Segal, 134 §294. ↩

- In LXX שָׁאַל מִן (shā’al min, “ask of,” “request”) is usually translated αἰτεῖν παρά. Cf., e.g., Exod. 3:22; 11:2; 12:35; 22:13; Deut. 10:12; 18:16; Judg. 1:14; 8:24; 1 Kgdms. 1:17, 27; 8:10; 2 Kgdms. 3:13; 3 Kgdms. 2:16, 20; 2 Esd. 8:22; 23:6; Ps. 2:8; 26[27]:4; Prov. 30:7; Zech. 10:1. In eight of these examples the compound form מֵאֵת is used instead of just מִן (Exod. 11:2; Judg. 1:14; 1 Kgdms. 8:10; 2 Kgdms. 3:13; 3 Kgdms. 2:16, 20; Ps. 27:4; Prov. 30:7). In five of these examples the compound form מֵעִם is used (Exod. 22:13; Deut. 10:12; 18:16; 1 Kgdms. 1:17, 27). ↩

- Two examples where LXX omits a preposition where MT has שָׁאַל מִן are:

וַיְהִי בְּבוֹאָהּ וַתְּסִיתֵהוּ לִשְׁאוֹל מֵאֵת אָבִיהָ שָׂדֶה

And at her coming, she pressed him to ask for a field from her father. (Josh. 15:18)

καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῷ εἰσπορεύεσθαι αὐτὴν καὶ συνεβουλεύσατο αὐτῷ λέγουσα Αἰτήσομαι τὸν πατέρα μου ἀγρόν

And it happened, when she came in, that she advised him, saying, “I will ask my father for a field.” (Josh. 15:18; NETS)

↩חַיִּים שָׁאַל מִמְּךָ נָתַתָּה לּוֹ

Life he asked of you, and you gave it to him. (Ps. 21:5)

ζωὴν ᾐτήσατό σε, καὶ ἔδωκας αὐτῷ

Life he asked of you, and you gave it to him. (Ps. 20:5; NETS)

-

Praying Like Gentiles Matthew’s Version Anthology’s Wording (Reconstructed) προσευχόμενοι δὲ μὴ βατταλογήσητε ὥσπερ οἱ ὑποκριταί δοκοῦσιν γὰρ ὅτι ἐν τῇ πολυλογίᾳ αὐτῶν εἰσακουσθήσονται μὴ οὖν ὁμοιωθῆτε αὐτοῖς οἶδεν γὰρ ὁ θεὸς ὁ πατὴρ ὑμῶν ὧν χρείαν ἔχετε πρὸ τοῦ ὑμᾶς αἰτῆσαι αὐτόν προσευχόμενοι δὲ μὴ βατταλογήσητε ὥσπερ οἱ ἐθνικοί δοκοῦσιν γὰρ ὅτι ἐν τῇ πολυλογίᾳ αὐτῶν εἰσακουσθήσονται μὴ οὖν ὁμοιωθῆτε αὐτοῖς οἶδεν γὰρ ὁ πατὴρ ὑμῶν ὧν χρείαν ἔχετε πρὸ τοῦ ὑμᾶς αἰτῆσαι αὐτόν Total Words: 34 Total Words: 32 Total Words Identical to Anth.: 31 Total Words Taken Over in Matt: 31 Percentage Identical to Anth.: 91.18% Percentage of Anth. Represented in Matt.: 96.88% ↩

- Note that Martin classified Praying Like Gentiles as a pericope which trends toward the “translation Greek” type. See Raymond A. Martin, Syntax Criticism of the Synoptic Gospels (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen, 1987), 114. Unfortunately, Martin lumped the On Prayer pericope (Matt. 6:5-6) together with Praying Like Gentiles (Matt. 6:7-8), which may have skewed his results. ↩

- On the role the Anthologizer played in breaking up the extended teaching discourse on prayer, see the introduction to the “How to Pray” complex. ↩

- See above, “Story Placement.” ↩

- See R. Steven Notley, “Can Gentiles Be Saved?” ↩