How to cite this article: Ze’ev Safrai, “Purity Halakha in the Story of the Hemorrhaging Woman,” Jerusalem Perspective (2025) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/30401/].

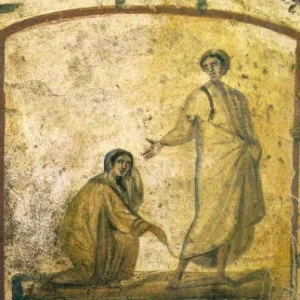

There are numerous instances of ancient Jewish halakhot that are attested in the New Testament Gospels.[4] For instance, sick people are frequently described as touching the fringes (צִיצִת [tzi·TZIT]) of Jesus’ garment (Matt. 14:36 ∥ Mark 6:56), which is evidence that Jesus wore tzitzit, and therefore observed halakhot pertaining to this religious observance. One of the more complex cases of halakha in the Gospels is that of the hemorrhaging woman who touches Jesus’ tzitzit.[5]

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

This halakhic interpretation of the story of the hemorrhaging woman who touched Jesus’ tzitzit can also clarify all the other cases of sick people touching only the tzitzit of Jesus’ garment (Matt. 14:36 ∥ Mark 6:56). The problem is that other explanations for this behavior are also possible—such as that the sick people were touching a holy item; or that touching tzitzit was an expression of awe of the man wearing them, a gesture of respect; there are also ideological or eschatological explanations. The advantage of the explanation I have suggested is that these other suggestions have no parallel in the ancient sources, and are not known from any other culture or period either, whereas my halakhic explanation is based on actual halakhic data, even though they are not spelled out in the New Testament sources.

- [1] It should be noted that according to early medieval commentators a garment and its wearer are considered a single unit (since a garment is secondary to the person). Therefore, if the woman had touched the garment, the person would be impure at the first level, and if she touched the tzitzit and if the tzitzit is not considered part of the garment, then the person and his clothes would be impure at the second level. According to this scenario Jesus would have become impure, but at a lower level. However, the commentators’ interpretation that ‘the garment is secondary to the person’ is not found in Talmudic sources, so it is doubtful whether this opinion was accepted in earlier periods. ↩

- [2] There are special laws for תְּרוּמָה (te·rū·MĀH, “tithe”), but this is not the place to discuss them. ↩

- [3] Mishnah translation from Sefaria.org. ↩

- [4] This article is an excerpt of a much longer investigation of the topic of halakha in the New Testament. For the full article, see Ze’ev Safrai, “Halakha in the Gospels,” Jerusalem Perspective (2024) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/28876/]. ↩

- [5] In Matt. 9:20 and Luke 4:44 the term is κρασπέδον (kras·PE·don, “hem,” “fringe”), but Mark 5:27 does not use the specific term. ↩

Comments 2

This is a nice summary of post-NT rabbinic halakha.

Here’s a ‘what-if’ that was not mentioned in the article:

The text says that the unclean woman became healed after touching Yeshua’s garment (regardless of the part that she touched). What do the ‘sages’ say about ritual purity in those cases? What is the LAW in the matter? Does the woman automatically become ritually pure? Does Yeshuah NOT become ‘unclean’? What is the legal determination for this scenario?

The reason for that account in the Gospels is to point out Yeshua’s power source: YHWH’s Spirit. MAGIC was at an all time high during 2nd Temple times. How does 2nd Temple magic play into understanding the meaning of this account?

What do the rabbis say about all of this ‘what-if’?

That’s what we want to know so we can get an idea of Matthew’s point about Israel (the sages) and Yeshua in his historical account.

Thanks…Chris

Dear ChrisH,

Thanks for your questions. I’ll try to address some of them here and point you to some further resources that might be helpful also.

First, the rules of ritual purity regarding the woman’s touch: Before the woman was healed she passed on her impurity to whatever susceptible items she touched. So if she had touched Jesus’ clothes, his clothes received first degree impurity. If she had touched Jesus himself he would have received a first degree impurity (Lev. 15:27). Because she was not healed until after the touch, her touch would definitely have contaminated. Her healing did not retroactively make her touch innocuous.

Second, the rules of ritual purity regarding the healed woman: As long as the woman’s hemorrhage continued she was impure without the possibility of purification (Lev. 15:25). As soon as she was healed (i.e., her bleeding stopped) she became eligible for purification (Lev. 15:28). The purification process lasted a minimum of seven days (Lev. 15:28) and was only completed after offering a sacrifice in the Temple (Lev. 15:29). But she stopped being a communicator of first degree impurity, so in a loose sense she could be called “pure” even prior to her purification rituals (Lev. 15:28).

All of these rules of ritual purity are set forth in the Torah and the rabbinic sages would have accepted them. The nuances come in with respect to questions like: What if the impure woman touched the tzitzit and not the cloak itself? The article above addresses the rabbinic answers to such questions.

As I see it magic does not play a role in the story of the impure woman. She touched Jesus’ tzitzit not because she regarded the tassels as magical charms, but because although she was convinced in Jesus’ power to heal she wanted to respect and preserve his ritual purity. If these were the woman’s motivations it is easier to understand why Jesus commended her faith: she was both bold and respectful. It is less easy to understand why Jesus would have commended her faith if she had believed in magical charms.

For additional resources, I recommend these JP articles:

Joshua N. Tilton, “A Goy’s Guide to Ritual Purity” (explaining from one Gentile to another the basics of how ritual purity worked) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/12102/]

Joshua N. Tilton, “What’s Wrong with Contagious Purity? Debunking the Myth that Jesus Never Became Ritually Impure” (explaining what’s wrong with the assumption that Jesus was immune to or able to reverse the effects of ritual impurity) [https://www.jerusalemperspective.com/29371/]