and

Now we will bring into consideration the statistics of “Double Tradition” (DT). I use this general term to refer to all Synoptic Gospel material that is attested by two Gospels, but not found in the third Gospel. Since the amount of material shared exclusively by Matthew and Luke is so much greater than the material shared by the other two pairs, this material has received the most attention from scholars. The shared materials of Matthew and Luke have their own special designation as “Q,” from the German word Quelle which means “source.” The intended implication of the German term is that in addition to using the Gospel of Mark the authors of Matthew and Luke shared a source that was not available to Mark—based on the conjecture that if Mark had known this source he would have used it.[10]

Premium Members and Friends of JP must be signed in to view this content.

If you are not a Premium Member or Friend, please consider registering. Prices start at $5/month if paid annually, with other options for monthly and quarterly and more: Sign Up For Premium

- [1] Even though this is not strictly "Double Tradition" in terms of exclusivity, I want here to examine the relationship of the two authors to each other to see whether their relationship is affected by the presence of a third author, or whether their relationship remains the same as when only the two were together exclusively, i.e., without the presence of the third author. ↩

- [2] The percentages used always apply to the whole corpus of the TT material of each respective Gospel. This usage of percentages serves the purpose of this general statistical research, but does not necessarily apply in the case of individual pericopae where considerable variations face the exegete. The aim here is to first establish the overall picture. ↩

- [3] IFS stands for Identical in Form and Sequence. For fuller definition of IFS and how IFS are counted, see “A Statistical Approach to the Synoptic Problem: Part 1” under the subheading "A Method for Eliminating Some of the Six Theoretically Possible Linear Relationships.” ↩

- [4] The 20% is not a problem because it can be explained the same way as in the competing scenario, viz.,

Mark's consistent degree of faithfulness to the first Gospel (Matthew in this scenario) is what causes the great drop in relationship to the text of the third Gospel (Luke in this scenario). ↩ - [5] We consistently measured these percentages according to the method of Morgenthaler’s Statistische Synopse, which is to say, e.g., when Mark brings a text for which there is a Lukan parallel, Mark’s text will, on the average, be composed of words 32% of which are identical in both form and sequence to the words of the Lukan parallels, and when Matthew has a text with a Markan parallel, Matthew’s text will, on the average, be composed of words 50% of which are identical in both form and sequence to the words of the Markan parallel. Robert M. Morgenthaler, Statistische Synopse, (Zürich and Stuttgart: Gotthelf, 1971). ↩

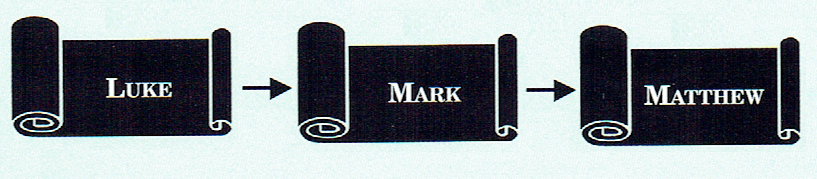

- [6] The theory of Lukan Priority is actually older than the theory of Markan Priority. Among the scholars who have espoused Lukan priority are Vogel (1804), Roediger, (1827), Schneckenburger (1827), Noack (1870), Mandel (1889), and Lockton (1922). Lindsey was unaware of the earlier proponents of Lukan Priority when he arrived at his solution to the Synoptic Problem. ↩

- [7] Franz Julius Delitzsch, Hebrew New Testament (British and Foreign Bible Society, 1891). ↩

- [8] This fact alone was only reason for delight. Lindsey was sensing for himself what scholars have sensed for centuries about the “translation-ese” feeling of much of New Testament Greek. It so often reminds of the Greek of the Septuagint, and in the case of the Septuagint there is no doubt that it was translated from Hebrew originals. ↩

- [9] See Halvor Ronning, “A Statistical Approach to the Synoptic Problem: Part 1—Triple Tradition.” ↩

- [10] There is a certain danger in the name “Q” because this conjecture is all too easily treated as an established fact. It is too easily supposed that it were already proven that this material existed in some separate source document (or oral tradition) that was available to Matthew and Luke but not available to Mark. Whether or not “Q” did exist separately from the source of those materials which are common to all three Synoptic Gospels is, however, a matter of debate. See the long section on “Q” in Thomas R.W. Longstaff, The Synoptic Problem: A Bibliography 1716-1988, (Macon, Ga.: Mercer, 1988). For a recent discussion, see Raymond Martin, Studies in the Life and Ministry of the Historical Jesus (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1995), Appendix 1, “Syntax Criticism of Q Material,” 73-83. Also debated is the question of its extent: whether “Q” contained only those materials found exclusively in Matthew and Luke, or whether it also contained some or all of the independent materials of Matthew and Luke (which are independent then only because the other of the two writers omitted that material for some reason), etc., etc. Or could “Q”even have contained most or all of the Gospel materials, so that each author was simply choosing those parts of it that served his purpose and omitting the rest? For extensive bibliography on each of these options, see Longstaff, The Synoptic Problem: A Bibliography. ↩