Gary Anderson’s recent monograph, That I May Dwell Among Them (2023),[1] is a welcome re-evaluation of the importance of Tabernacle/Temple and sacrifice for Christian readers. Even now it is not uncommon to hear Christians claim that with the crucifixion of Jesus sacrifice is no longer meaningful and the Temple is drained of its former significance. Anderson’s book examines seriously what that significance was for ancient worshippers who made pilgrimage to the Temple and offered sacrifices at its altar. For them, sacrifice in God’s holy presence was the pinnacle of human-divine interaction. Anderson also points out that, far from having lost their significance, the imagery and theology of the Tabernacle were essential for the early Christians, who struggled to articulate their understanding of who Jesus was, and who grappled to give the senseless and shameful execution of their Messiah a redemptive meaning and a divine purpose.

In the first chapter of Part One of his book Anderson examines the scriptural accounts of the inauguration of the Tabernacle, finding parallels between it and the creation narrative in Genesis. For the writers of Scripture, the erection of the Tabernacle was viewed as the purpose and crowning achievement of creation: God had come to dwell amidst the world he had spoken into existence with the people for whom he made it.

In the second chapter of Part One Anderson helps readers appreciate the sometimes tedious descriptions of the Tabernacle’s design and furnishings. For non-priests, who could not enter the holy precincts, these descriptions allowed lay Israelites to enter the Holy of Holies in their minds. The furnishings of the Tabernacle they could see became almost visible manifestations of the divine presence. Just as a country music fan might marvel to strum Hank Williams Sr.’s guitar, so the ancient worshippers stood in awe of the holy objects of the Temple, which gave them a physical connection to the ineffable and transcendent presence who dwelt therein.

The third chapter of the book delves into the purpose and meaning of sacrifice. Anderson rejects the commonly held view that sacrifice was primarily about atonement. The purpose of sacrifice was not to appease an angry God but to establish an ongoing relationship. The Tamid sacrifice—the most important of the offerings, which was offered twice daily, morning and evening, even on the Sabbath—was not a sacrifice of atonement or propitiation but a perpetual sacrifice that continually reinforced Israel’s relationship to God. Their constant service at the altar reminded Israel of their utter dependence on the One to whom they offered sacrifice.

Further in the book Anderson explores how in later Jewish writings the Tamid sacrifice came to be understood as a reminder and re-enactment of Abraham’s offering of Isaac on Mount Moriah. The association of the Tamid offering with the Binding of Isaac was by no mere fancy, the Scriptures themselves already hinted at this connection. By making this association, Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice all he held dear to the God he both loved and obeyed became the theological basis for interpreting the significance of sacrifice. God’s constant memorial of Abraham’s (and Isaac’s) obedience became the source of blessing when Israel followed in their ancestors’ faithfulness and became a bulwark against God’s displeasure when Israel strayed into disobedience.

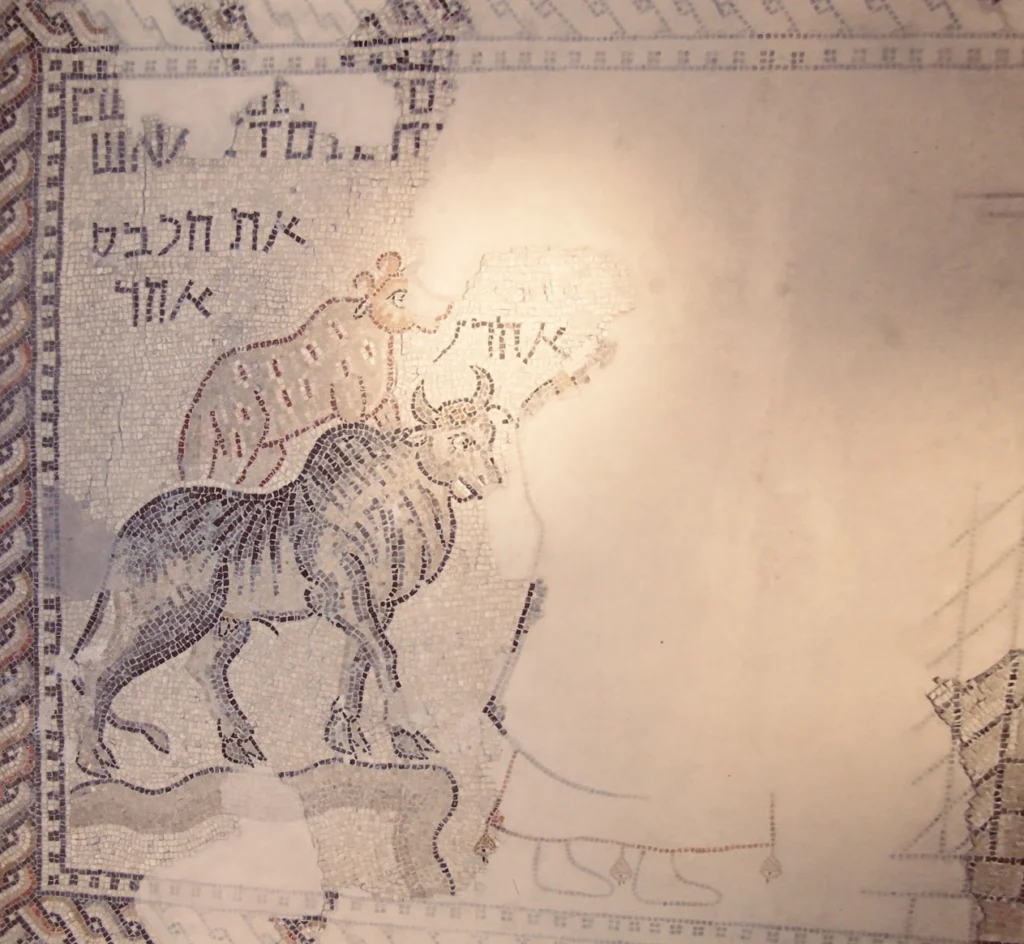

One of the places where the connection between the Tamid sacrifice and the Binding of Isaac is visually represented is in the carpet mosaic of the ancient synagogue in Tzippori (Sepphoris). One of the top panels of the mosaic depicts the Tamid sacrifice, as indicated by a quotation from Exod 29:39: “One sheep [shall you offer in the morning].” This panel is balanced near the bottom of the mosaic by a panel depicting the Binding of Isaac.

At the end of the book Anderson considers how a fuller appreciation of Israel’s understanding of the divine presence in the Temple and the divine service at the altar can give Christians better tools and deeper ways to comprehend the Christian doctrines of Incarnation and Atonement.

Anderson’s book is a revealing and thought-provoking analysis of an often neglected and under-appreciated aspect of Scripture, which JP readers are sure to enjoy.[2]